A tale of two demagogues

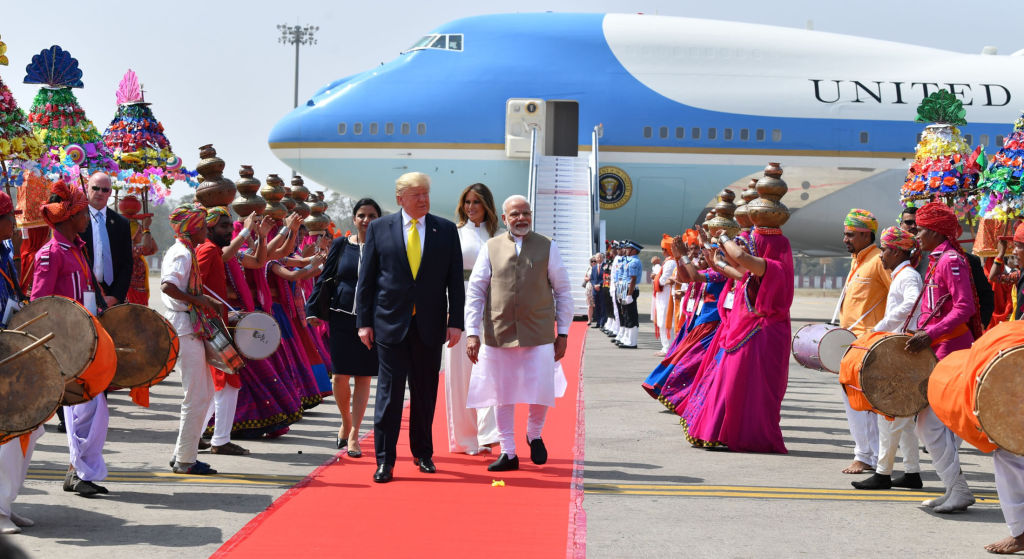

‘America loves India’, declared US President Donald Trump on this week’s visit to the Indian state of Gujarat, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s power base. Before a crowd of more than 100,000 in the world’s largest cricket stadium, the two leaders triumphantly celebrated the deepening friendship between their countries—or, to be more precise, between their brands of charismatic populism. Not even Trump’s repeated mangling of Indian names during his speech could dampen Modi’s glow.

But Trump’s visit to India wasn’t the major historical moment of which he and Modi boasted. Although Modi described the US–India relationship as ‘the most important partnership of the 21st century’, it may never match the ever-deepening ties between China and Russia. After all, conventional authoritarians find it far easier than populists to unite behind a common vision of their global interests. The China factor is of course important for both the United States and India, but it is not sufficient to transcend their cultural differences and deeply divergent economic interests (especially regarding trade).

Having said that, another type of history was in the making during Trump’s visit. But it was very different from the sort that he and Modi had envisaged.

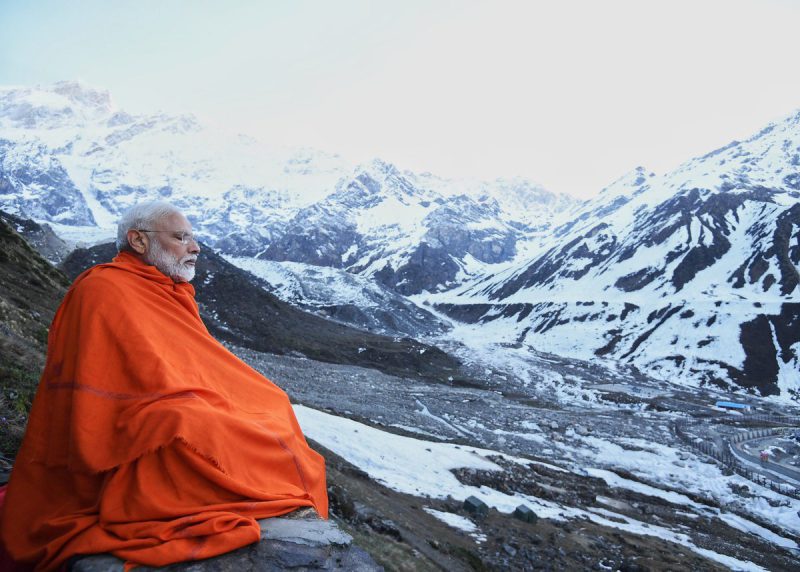

When trying to describe the two leaders’ recent meetings in India, the expression ‘bonfire of the vanities’ inevitably comes to mind. In an atmosphere of abject flattery and rarely matched pomposity, Trump and Modi recognised similar qualities in each other. Watching them live on television, I could only think back to the iconic scenes from Charlie Chaplin’s cinematic masterpiece, The Great Dictator. Chaplin’s farce, it seems, is now repeating itself—this time as tragedy.

For Trump, who is gearing up for his re-election campaign, India was a perfect place to test his message to US voters—and in particular to America’s successful four-million-strong Indian diaspora, which tends to vote Democratic. Trump’s message was simple: if India, the world’s largest democracy, is welcoming him like a hero and a star, then why should some (clearly unpatriotic) Americans reject him as if he were a threat to democracy? Indeed, Trump seemed to be claiming the protection of both Modi and Mahatma Gandhi.

The US president’s visit brought similar benefits for Modi. Many Indians detest the prime minister’s brand of religious nationalism, and Delhi currently is experiencing its worst Hindu–Muslim violence in decades. But Modi can now say to his opponents that the leader of the world’s most powerful democracy doesn’t seem to mind how India treats its Muslim minority or how it behaves in Kashmir.

Having thus bolstered each other’s legitimacy with kudos and absolution, Trump and Modi could move from public pageantry to the more serious and divisive matters of China and trade. That brought to mind conversations I had in the early 2000s with Robert Blackwill, a seasoned diplomat who was the US ambassador to India at the time. Blackwill’s main goal was to make America recognise (or, arguably, rediscover) the vital importance of India, the world’s largest democracy, to the US. For him, democracy was not a vague, empty word, but rather the key to building a privileged relationship with India. But at that time, of course, neither country’s politics had yet been overrun by illiberal populists.

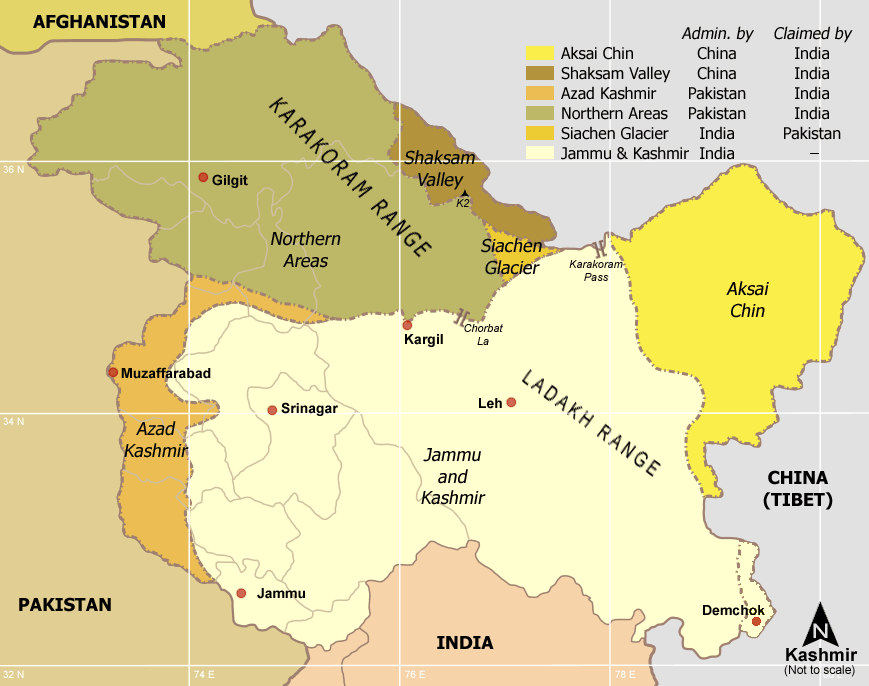

To be sure, US–India relations have always been complex. As early as the 1950s and 1960s, both countries viewed China as a threat. After India lost a 1962 war with China, it signed an air-defence agreement and shared intelligence with the US, while America also provided economic and military assistance.

But the two countries soon began to fall out regarding the urgency of the Chinese threat. Indian leaders felt betrayed when the US, under President Richard Nixon, began a process of rapprochement with China. As a result, Russia and India moved closer towards each other, leading America in turn to shift its regional attention to Pakistan.

Then came India’s decision to become a nuclear power. The US initially was angered by Indian stubbornness over the issue, but subsequently resigned itself to a reality it was unable to prevent. And although US leaders thought that a nuclearised India was probably bad for the world, the country’s arsenal was at least a useful deterrent vis-à-vis China.

Yet, while a shared mistrust of China may be a necessary precondition for a successful US–India relationship, it is not a sufficient basis for a close and durable alliance between two complex giants. In fact, if the US and India are no longer united by a deep and sincere commitment to democracy, then India may one day decide that its interests lie in seeking its own rapprochement with China, a more predictable global power.

Finally, US–India trade frictions will persist, despite the warm relations between Trump and Modi. Perhaps tellingly, the event in the Gujarat cricket stadium ended with the Rolling Stones song ‘You can’t always get what you want’.

Economic nationalism is on the rise and democracy is on the wane. Given these worrying trends, what happened in Gujarat between Trump and Modi may yet come to be seen as dystopia’s apotheosis.