Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

The confluence of forces built around shared unease and growing anxiety over the implications of China’s rapid military expansion, salami-slicing territorial creep and ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy is fertile ground for the revival of the quadrilateral security dialogue (Quad) between Australia, India, Japan and the US. The four democracies share the strategic assessment of China as a disruptive force in the Indo-Pacific.

Quad 1.0 was interred in 2008 when Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, bowing to China’s sensitivities, pulled Australia out. The concept went on hold with Shinzo Abe’s loss of office in Japan, the advent of the Obama administration in the US, and the anti-American bent of Manmohan Singh’s communist party and other left-leaning allies in India.

As part of a fundamental reorientation of India’s foreign policy, PM Narendra Modi began aggressively pursuing diplomatic initiatives to the east, including investing in personalised diplomacy with China’s President Xi Jinping as well as with Abe. Australia’s unease has been rising over aspects of China’s behaviour in the region and interference in Australian politics and public life. The Trump administration has identified China as the top US security threat. And Japan is trying desperately to adjust to the shape of Asia’s new cold war.

China’s re-emergence as a comprehensive national power raises multiple points of concern that provide the backdrop to the fresh interest in Quad 2.0. China has morphed from its historical identity as a continental power into a modern maritime power with growing power-projection capability across the Indo-Pacific. It has followed a string-of-pearls strategy in the Indian Ocean, backed by a growing naval capability, to choke India around its littoral and to check it on land by courting Nepal and its all-weather friend Pakistan. It has engaged in assertive behaviour in the East and South China seas to build sprawling, interlinked militarised facilities on remote and uninhabited islands—many of them disputed on ownership—to challenge US strategic primacy.

Shashi Tharoor, former chair of India’s Parliamentary Standing Committee on External Affairs, rightly notes that the 15 June military clash with China in the Galwan Valley in Ladakh presents India with the stark choice of capitulating to China’s military blackmail or embracing the US free of the historical burden of anti-Americanism. Gautam Bambawale, the recently retired Indian ambassador to China, thinks the clash will mark the date on which China finally ‘lost India’ strategically.

Australia’s former ambassador to China Geoff Raby notes: ‘[A] series of important announcements … have made it clear that the Australian government now regards China as a strategic competitor and a revisionist power that must be resisted.’ China’s retaliatory measures against Australia include impediments on beef, barley, students and tourists, as well as aggressive statements from Chinese diplomats.

On 30 June, after China enacted a sweeping new national security law for Hong Kong, Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga called the move ikan (regrettable), which is just one step short of the most critical word in the Japanese diplomatic lexicon, hinan (denounce). As the situation in Hong Kong gradually deteriorated, Japanese officials had used incrementally stronger words—from chūshi (closely monitoring) to yūryo (seriously concerned).

The 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations issued an unusually tough statement on China on 27 June reaffirming the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea as the proper basis of sovereign rights and entitlements in the disputed South China Sea.

On 13 July, following the dispatch of two aircraft carriers to take part in one of the largest naval exercises in recent years in the South China Sea, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called out China’s behaviour as illegal in a rare direct challenge to Beijing. ‘The world will not allow Beijing to treat the South China Sea as its maritime empire’, he said. Full-spectrum China–US strategic jostling will peel away the layers of safety nets against deliberate or inadvertent military conflict.

Australia, Japan and the US were drawn to the ‘Indo-Pacific’ conceptual frame as a convenient analytical tool to incorporate India into their strategic calculus. It integrates geography, the ‘free and open’ principle and democratic values into one strategic construct.

However, the level and quality of economic interaction of the four Quad partners with China vary enormously, as do their territorial disputes and their fears of entanglement in others’ quarrels. There can be no expectation of automatic military assistance in any armed conflict with China arising from the territorial disputes between Japan and China and between India and China. The volatility and erratic decision-making style of the Trump administration and its transactional approach to foreign policy raise doubts about the reliability of its security guarantee. All this explains the wariness towards the Quad by the partners. That is likely to subside in the rapidly changing geopolitical landscape.

The origins of the Quad are entirely benign. After the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami on Boxing Day 2004, the four navies closely coordinated disaster relief operations and gradually consolidated habits of cooperation in the vast maritime space of the Indo-Pacific. Even today there is no appetite among any of the four for an upgrade of the Quad from a web of intersecting bilateral-cum-trilateral relationships resting on shared strategic worldviews and promoting habits of cooperation to a hard-edged anti-China security alliance.

However, caught between an increasingly assertive and bellicose China and a US that grows more unpredictable and less reliable by the month, Australia, India and Japan are having to ‘thread the needle’ of a fraught future for the Indo-Pacific amid the collapsing pillars of the liberal international order. Nevertheless, while the stated message is an informal security dialogue, the message as received in Beijing is that the Quad is a coalition to contain China.

To understand why, China’s leaders might want to hold their statements and actions to the mirror.

After last month’s clash in the Ladakh region’s Galwan Valley killed 20 Indian soldiers and an unknown number of Chinese troops, the two countries are settling in for a prolonged standoff on their disputed Himalayan frontier, even amid reports of a disengagement at the site of the clash. More important, the recent skirmish may have highlighted a broader shift in Asian geopolitics.

At first glance, this suggestion may seem exaggerated. After all, China and India had been making a decent fist of living with each other. Although they haven’t reached a durable settlement of their disputed 3,500-kilometre border, not a shot had been fired across the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in 45 years. Meanwhile, bilateral trade climbed to US$92.5 billion in 2019 from just US$200 million in 1990.

Of course, bilateral tensions also reflect long-term disagreements that go beyond territorial disputes, such as China’s ‘all-weather’ alliance with Pakistan, and India’s hospitality towards the Dalai Lama, to whom it granted refuge when he fled Tibet in 1959. But neither country has been swept up by these issues. When China declared that the border dispute could be left to ‘future generations’ to resolve, India was happy to go along. India also endorsed the ‘one China’ policy, and shunned United States–led efforts to ‘contain’ its northern neighbour.

But the latter policy, in particular, has played into China’s hands. The People’s Liberation Army has taken advantage of the seemingly benign situation to undertake repeated military incursions.

Each one was minor. China would take a few square kilometres of territory along the LAC, declare peace, and then fortify its new deployment. As a result, each mini-crisis brought a ‘new normal’ on the LAC. And it was always China’s position that improved.

By the time ‘future generations’ settle the border dispute, China’s leaders seem to hope, the reality on the ground—as well as the broader balance of economic and military strength—will heavily favour China. Any agreement will reflect that. In the meantime, border incidents keep India off balance and show the world that it’s not capable of challenging China, let alone underwriting regional security.

India has reinforced its military assets on the LAC to stave off deeper incursions, and hopes to press China to restore the status quo ante through diplomatic or military means. For example, it could capture land elsewhere on the LAC to use as leverage. But that’s easier said than done.

Meanwhile, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has claimed that China is not in control of his country’s territory. This looks suspiciously like a surrender to the new reality in the Galwan Valley and Pangong Lake, where the PLA has established positions that didn’t exist before May. It could embolden China to pursue additional small gains across the LAC.

India has pursued some economic retaliation, banning 59 Chinese apps on data-security grounds. It is likely soon to bar Chinese companies from other lucrative opportunities in its vast market. But given India’s dependence on Chinese imports—including pharmaceuticals, automotive parts and microchips—excessive restrictions could amount to cutting off its nose to spite its face.

India has only two real strategic options: kowtow to China or align itself with a broader international coalition aiming to curb China’s geopolitical ambitions. Despite Modi’s apparent capitulation, there’s reason to believe that India may choose the latter approach.

For starters, India has lately increased cooperation with the US military. In 2016, it concluded a logistics support agreement, and in 2018, it reached a communication security agreement and an accord on geospatial cooperation.

India has embraced, at least rhetorically, the US concept of a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’, and is gradually abandoning its reluctance to participate in the US-led ‘Quad’, an informal four-country grouping (which also includes Australia and Japan) focused on countering China’s regional ambitions. The foundations have been laid for a more substantive strategic shift.

India has obvious incentives for such a shift. Beyond its belligerence on the LAC, China has increased its support for Pakistan, spending more than US$60 billion on a highway to the Chinese-run port of Gwadar. A ‘peace strategy’ towards these two adversaries holds no attraction for an Indian government that has stripped Jammu and Kashmir of its autonomy, in an open challenge to Pakistan.

Moreover, India sees China’s hand in its difficulties with other neighbours, especially Sri Lanka and Nepal, whose communist government has begun questioning its own border with India. China has further rankled India by opposing its aspirations to a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council, blocking it from joining the Nuclear Suppliers Group, and making territorial claims in the northeastern Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh.

India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party is not averse to a policy shake-up. In May, two BJP MPs thumbed their noses at China by ‘attending’ the virtual swearing-in ceremony of Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen. India has also criticised China’s Belt and Road Initiative, refusing to attend BRI forums in 2017 and 2019. And it has withdrawn from the Asia-wide Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership over concerns about Chinese dominance.

But there remain significant potential barriers to a strategic realignment. Such an approach would mark a major departure from India’s traditional obsession with protecting its ‘strategic autonomy’—a legacy of two centuries of colonial rule, reflected in India’s role in establishing the Non-Aligned Movement during the Cold War.

Furthermore, India has no interest in putting all of its strategic eggs in one basket. It remains heavily dependent on Russian military equipment and supplies (though it has recently diversified its purchases), and Donald Trump’s US isn’t exactly a reliable partner. But is this a worse option than capitulating to China?

Eight months ago, Modi hailed ‘a new era of cooperation’ with China. Though it’s too early to say with certainty, that era may soon be buried in the snowy heights of the Himalayas.

The ongoing standoff between Chinese and Indian forces along the two countries’ disputed Himalayan border recently resulted in the first troop casualties there in decades, with some Indian soldiers killed in particularly brutal fashion. The intensity of China’s multiple cross-border incursions suggests approval from the highest levels of the Chinese government.

Satellite pictures confirm that Chinese forces have occupied at least 60 square kilometres of territory that India claims as its own. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has downplayed this uncomfortable reality, perhaps out of concern that publicly acknowledging the truth would inflame domestic public opinion and fuel a highly undesirable escalation of tensions. A less benign interpretation, however, is that the government is embarrassed, because its claim to be more muscular than its predecessor in confronting external aggression has been proven hollow.

But China’s recent sabre-rattling may paradoxically benefit India by jolting it out of one of its periodic stupors. After its disastrous 1962 war with China, for example, India undertook a sweeping modernisation of its military and subsequently won a decisive victory in the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War.

Similarly, after its own misguided economic policies raised the spectre of mass starvation in 1966–67, India launched the ‘green revolution’, and today has nearly 100 million tons of grain stocks. And, following its massive balance-of-payments crisis in 1989–91, India initiated a historic economic liberalisation program that ushered in a quarter of a century of unprecedentedly rapid growth.

In each case, a crisis served as a kick in the pants. China has now delivered another. The Chinese Communist Party has been adept at leveraging the country’s humiliation at the hands of foreign powers in the 19th century to drive domestic change while preserving its own political monopoly. But the CCP’s recent aggressive behaviour towards India mimics that of China’s former imperial masters—and will likely have similar consequences.

First, China’s show of force will set back its relations with India by decades. Since the turn of the century, Indian policymakers have wrung their hands over how to handle China’s extraordinary rise. They are well aware of how China has sought to stymie India, whether by offering neighbouring Pakistan carte blanche regarding cross-border terrorism, blocking India in different international forums, or making strategic inroads in its neighbourhood. But Indian governments, recognising their country’s weakness, have been loath to poke the dragon with which it shares a border more than 4,000 kilometres long.

India will now be less inhibited about deepening ties with the other three members of the ‘Quad’ (Australia, Japan and the United States) and more forcefully embracing the ‘Indo-Pacific’ concept. And it will be increasingly wary of participating in Chinese-led multilateral forums, and, where possible, will seek to hinder China’s efforts to establish a Sinosphere.

Second, it has become abundantly clear that India’s military inferiority to China reflects a widening economic gap. The previous Indian government, under Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, raised the economy to new heights in its first term (2004–09), and lowered it to new depths in its second (2009–14). But, under Modi, India’s economy has been spinning its wheels, and reform has now become an existential necessity for national security.

Third, India will now accelerate military changes. Although Modi’s government loves to talk tough, military expenditures have declined from 2.9% of GDP in 2009 to 2.4% last year.

The government’s populist policy of sharply raising armed forces pensions has meant that India’s defence budget this year allocated more money to military retirement benefits than to salaries. Indeed, defence pensions as a share of non-pension defence spending has quadrupled, from less than 10% in the late 1980s to more than 40% this year. And with salaries and pensions accounting for nearly three-fifths of Indian defence spending, there is little left to invest in modernisation. Whereas China spends more than two-fifths of its defence budget on modernisation, and Pakistan more than one-third, the share in India’s case is barely one-quarter.

Finally, while Modi’s ruling party has polarised Indian society around religion, China has now inadvertently supplied the glue to bind Indians together—if only in shared hostility. Chinese President Xi Jinping seems to have a unique ability in that regard.

For example, Australians’ trust in China has fallen to its lowest ever level. Australia, as much as any Western country, had previously sought strong ties with China. But when the Australian government called earlier this year for an independent inquiry into the origins of Covid-19, China retaliated by blocking Australian imports, underscoring the degree to which it is now using economic coercion against its critics.

Likewise, a Pew Research Center survey in March found that a record 66% of Americans had an unfavourable view of China. And China’s aggressive stance towards Hong Kong ensured that incumbent Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen comfortably won re-election in January, after the opposition Kuomintang had seemed poised to win on a platform of closer economic links with China.

Of course, India being India, there will be no seismic changes. But the country’s foreign policy and the direction of its economic and military reforms will increasingly reflect the challenge posed by China, which Indians now regard as their principal enemy. Ironically, as India seeks to escape China’s shadow, it will have its powerful neighbour to thank for finally triggering changes that should have happened long ago.

In this episode, ASPI’s Michael Shoebridge speaks to Shashank Joshi of The Economist about India–China border tensions plus the risk of further escalation, the politicisation of casualties and the impact on the broader relationship between India and China.

Research intern Tracy Beattie speaks to senior analyst Malcolm Davis about the latest developments on the Korean peninsula, including North Korea’s destruction of the joint liaison office in Kaesong, the role of Kim Jong-un’s sister, Kim Yo-jong, in that plan and the US response to the situation.

And our cyber centre’s Louisa Bochner speaks to analyst Alex Joske about his report, The party speaks for you, which looks at China’s united front system of overseas influence and interference operations in politics and diaspora communities.

The recent developments in Ladakh on the disputed border between India and China were shocking and tragic. The clash in Galwan Valley last week has opened up a deep fissure in India–China ties, spawning tensions that could even escalate into an all-out-war. The latest reports suggest the Indian armed forces have begun a rapid mobilisation and the Chinese military has been shoring up its positions, even as political efforts are on to defuse the crisis.

With a spiral of escalation building, a conflict so far limited to the Line of Actual Control with China could see other theatres open up, including one in the Indian Ocean. Unlike on the land border, where China has a relative advantage of terrain, military infrastructure and troop strength, India is better placed at sea. In the Eastern Indian Ocean through which most of China’s cargo and energy shipments pass, the Indian Navy is the dominant force.

In recent years, the Indian Navy has sought to consolidate strength in India’s near seas through its mission-based deployments. Since 2017, Indian warships have patrolled Indian Ocean sea lanes and choke points, including the approaches to the Malacca Strait. In its bid to keep track of Chinese submarines in the Eastern Indian Ocean, the Indian Navy has also been operating P-8I maritime patrol aircraft from the Andaman Islands. A chain of radar stations along the Indian coast has helped in providing better information about maritime movements, and a fusion centre in Gurgaon near New Delhi is helping manage tactical information in the near seas.

China, too, has been probing the subcontinental littorals. Since 2013, when it first sent a submarine to Sri Lanka, the People’s Liberation Army Navy has significantly expanded its military and civilian expeditions in South Asia. In recent months, China has sent intelligence ships and survey and research vessels into the Andaman Sea, attempting to track Indian naval activity in the region. While it has so far desisted from challenging the Indian Navy, the PLAN’s pattern of deployment suggests an aspiration for a sustained presence in areas of overlapping interest with India.

Three aspects about a possible India–China maritime conflict seem relevant. First, unlike with Pakistan, when the Indian Navy established a loose blockade in the northern Arabian Sea during Operation Talwar in 1999 and Operation Parakram in 2001, and again after the Balakot attack last year, an aggressive barricading approach in China’s near seas would be unviable. India has virtually no presence east of Malacca, and unless it acts in concert with the US, Vietnam and Japan in the Pacific littorals, the Indian Navy cannot hope to take on the PLAN in its backyard.

What seems more realistic is an interdiction strategy aimed at choking Chinese trade passing through the Indian Ocean sea lines of communication. A vast majority of China’s oil shipments, container vessels and bulk cargo traffic approaches the Malacca Strait through the 10 degree channel between Andaman and Nicobar. Observers say the Indian Navy could stifle the flow of Chinese traffic, while aggressively patrolling the Indian Ocean chokepoints, keeping an eye on Chinese naval reinforcements.

Here too, however, there are likely to be complications. With a significant share of seaborne trade moving in Chinese-flagged vessels, an Indian interdiction strategy could result in regional blowback against New Delhi. Many Indo-Pacific states would view India’s disruption of regular shipping in an international sea lane as a hostile act that imposes unacceptable costs on neutrals. To avoid such a scenario, Indian warships will need to be careful in targeting Chinese-flagged vessels, and refrain from the unnecessary use of force.

Second, the Indian Navy will need to focus on denying the PLAN tactical space in India’s near littorals. Through the use of submarines and anti-submarine-warfare-capable air assets, India would seek to restrict China’s freedom of operation in the littorals. Part of the strategy would be to position Indian naval assets on the east coast and in the Andaman island bases to keep up a high tempo of operations in regional hotspots.

Denying China use of India’s near seas won’t be easy. With a vast fleet comprising nuclear attack submarines, guided missile warships, amphibious carriers and a host of other capable war-fighting platforms, the PLAN is the world’s second most powerful navy, and should not be underestimated. But it is constrained by the absence of operational logistics, ship-based air cover and land-based maritime reconnaissance capabilities in the Indian Ocean—gaps that the Indian Navy would hope to exploit.

Third, India should expect China to use its Belt and Road Initiative in South Asia to reduce its tactical deficit in the Indian Ocean. In Hambantota in Sri Lanka, Chittagong in Bangladesh and Sittwe in Myanmar, where China is building maritime infrastructure, the PLAN is likely to press for a greater presence to overcome logistical constraints in the Indian Ocean. Already China is constructing a naval base for Bangladesh in Cox’s Bazar that could be used to position naval ships and store military supplies.

The imperative for India is to track Chinese naval activity and warship movements along the Bay of Bengal rim. As it seeks to expand basing facilities for submarines and ASW aircraft in the Andaman Islands, the Indian Navy would look to position long-range surface-to-surface missiles on the island chain to more directly threaten Chinese naval deployments.

Needless to say, a naval conflict with China in the Indian Ocean would be an ‘acid test’ for India—one that would require considerable planning and effort to prevail over the adversary.

The recent deaths of at least 20 soldiers along the contested border at Ladakh between India and China represents the largest loss of life from a skirmish between the two countries since the clashes in 1967 that left hundreds dead. It also highlights the tensions that have been building along the Line of Actual Control since early May.

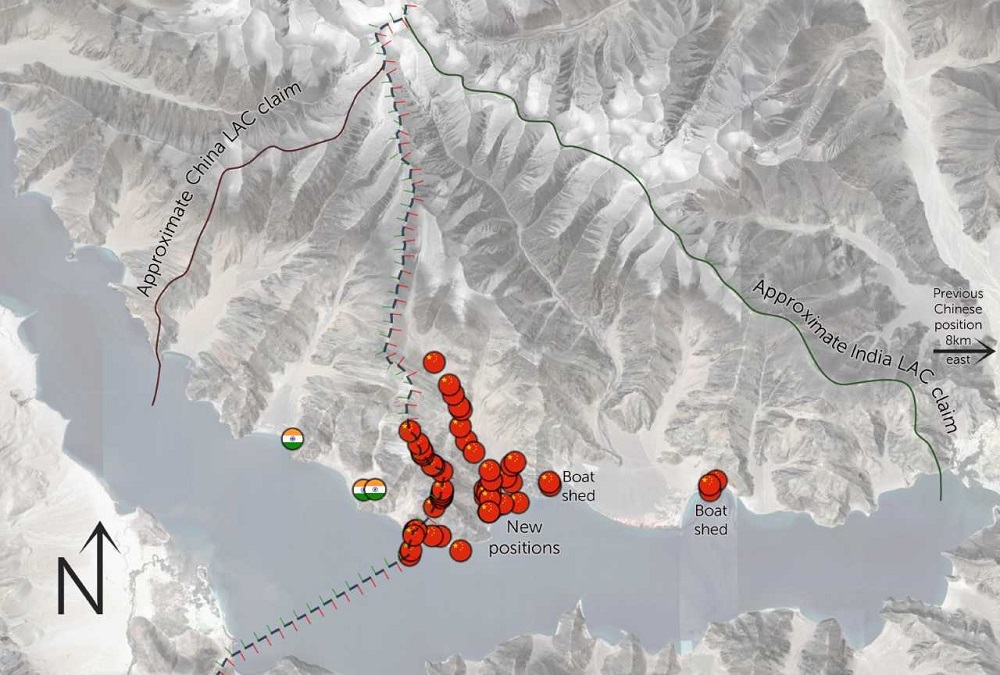

Using this satellite imagery, I will try to illustrate the approximate reality on the ground. My analysis disproves some of the more extreme claims that have been made about the incident, such as that thousands of Chinese soldiers have crossed the LAC and encamped in Indian-controlled territory. The satellite pictures also highlight the obvious threats to a peaceful status quo that exist along the western sector of India’s border with China.

The analysis includes evidence that strongly suggests People’s Liberation Army forces have been regularly crossing into Indian territory temporarily on routine patrol routes.

The details of this week’s clashes are still murky. But based on recent satellite imagery and media reporting, it appears the bulk of casualties were the result of soldiers falling during hand-to-hand fighting along a steep ridgeline that marks the LAC. The small area that is at the heart of this dispute appears to straddle the LAC and likely houses less than 50 Chinese troops.

Neither Beijing nor Delhi considers the loosely demarcated line that separates the two countries in Ladakh to be an authoritative border. It approximates areas of territorial control established at the end of the 1962 Sino-Indian War when China withdrew from much of its captured territory on the Himalayan plateau.

The border standoff at Ladakh has become a politically charged issue in India. The Indian government has revealed few details about the situation over the past few weeks. Former Indian Army officers, however, have been providing information to journalists and the media have been consistently painting a picture of a substantial conflict, often involving claims of the incursion of 10,000 PLA troops into undisputed Indian territory.

The reality is less dramatic, but does represent a significant change to the status quo along the India–China border that threatens to escalate.

By analysing satellite imagery from late May and early June it’s possible to make informed judgements about the positions of forces at multiple hotspots.

Along the India–China border there are three key areas that produce the majority of tension between the two countries: Arunachal Pradesh; Sikkim and nearby Doklam (the site of a major skirmish in 2017 that saw Indian troops enter Bhutanese territory to prevent the completion of a strategic road being built by China); and Ladakh.

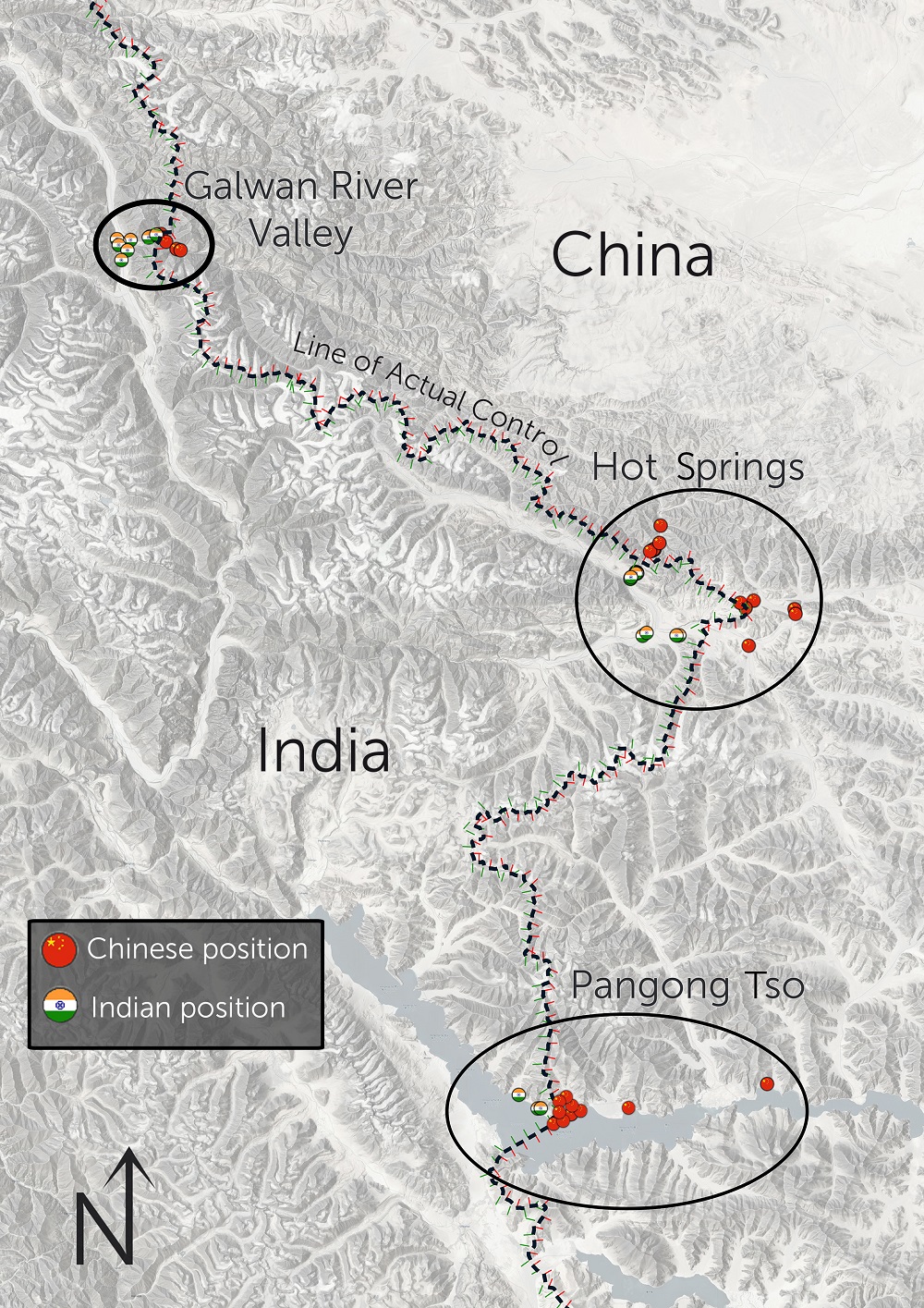

The build-up of troops and military positions in recent months has been mostly in the Ladakh sector. Developments have occurred in three strategic areas along the LAC: the Galwan River Valley, where this week’s deadly clashes occurred; Hot Springs, where satellite evidence suggests that Chinese forces have regularly entered Indian territory; and the Pangong Tso.

In all these key areas, both sides have steadily built up troop numbers and military positions close to the LAC (see map 1).

Map 1: Ladakh sector, showing Line of Actual Control and key areas

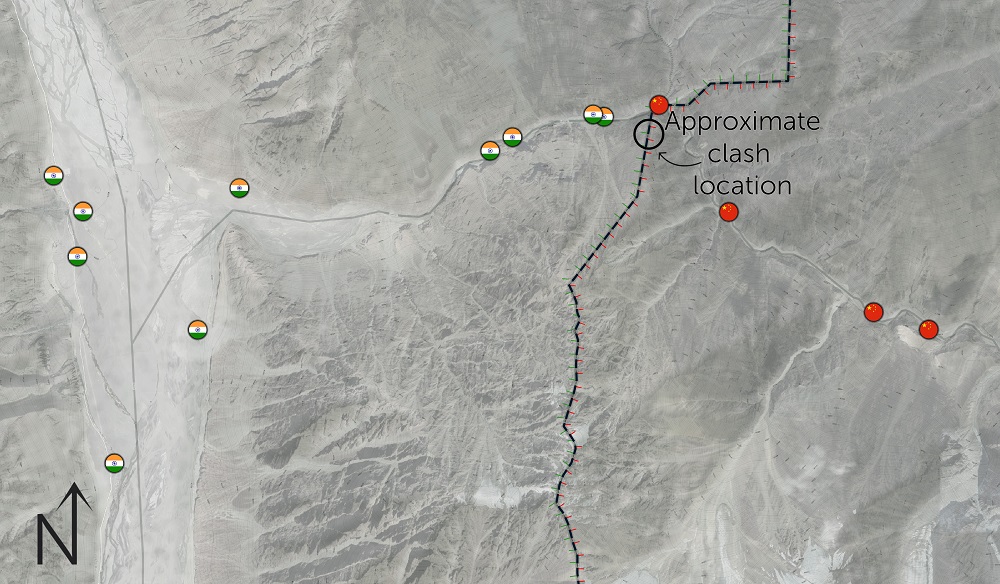

The most significant hotspot right now, where prior to disengagement Indian and Chinese troops were positioned within a few hundred metres of each other, is in the Galwan River Valley. Until May, the PLA didn’t have positions within the valley, despite several kilometres being on the China-controlled side of the LAC. However, recently established Indian positions closer to the LAC, and the construction of a road to supply these positions, appears to have prompted the PLA to establish a number of significant positions and move up to 1,000 soldiers into the valley.

China is reportedly now laying claim to all of Galwan River Valley.

One key position, referred to in the media as Patrol Point 14, is a sandbank along the LAC that has been occupied by a small number of tents and likely fewer than 50 Chinese soldiers. India and China had reportedly agreed that this position would be dismantled as part of efforts to defuse tensions between Indian and Chinese forces. The move to dismantle the camp is apparently what sparked the recent deadly clashes.

The disposition of forces in this area is shown in map 2.

Map 2: Galwan River Valley, showing approximate location of clash

Strategically, the PLA’s advances into the Galwan River Valley provide a superior vantage point for observing a supply route used by the Indian Army to reach its northernmost base, and the world’s most elevated airfield, Daulat Beg Oldi.

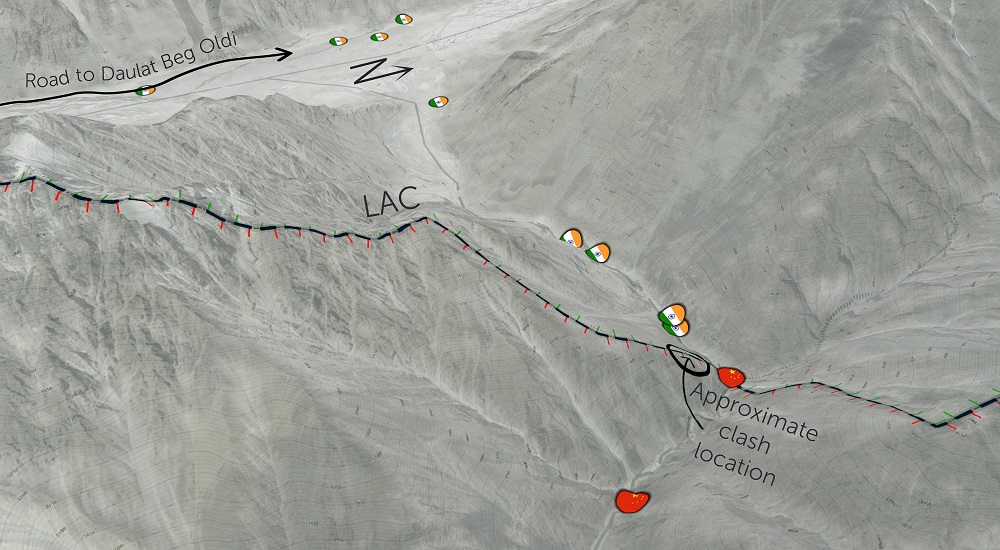

From ridgeline positions, PLA forces would be able to monitor all traffic on the recently completed Darbuk–Shyok–Daulat Beg Oldie road, a strategic route that abuts the LAC through much of Ladakh and has taken nearly 20 years to build. Additional Indian military bases have been constructed along this road recently. An oblique view of the Galwan and Shyok valleys is shown in map 3.

Map 3: Galwan River Valley, oblique view of approximate location of clash relative to road to Indian military base

Satellite imagery provided by Planet Labs taken on 16 June, the morning after the deadly clash along the LAC, shows both the Indian and Chinese forwardmost positions that had been dismantled over the past week (maps 4 and 5). A temporary Indian position (likely a casualty collection point), however, had been set up within 50 metres of the LAC (map 4). In addition, a group of around 100 trucks can be seen on the Chinese side of the border near other positions in the valley (map 5). It’s not clear if these trucks are reinforcing the area with troops or dismantling positions in accordance with the disengagement agreement between India and China.

Map 4: Galwan River Valley, showing dismantled and temporary Indian positions, 16 June 2020

Satellite image from Planet Labs.

Map 5: Galwan River Valley, showing partially dismantled Chinese position and trucks, 16 June 2020

Satellite image from Planet Labs.

South of the Galwan River Valley lie two other significant hotspots, the Hot Springs area and the Pangong Tso.

In Hot Springs, most of China’s development of infrastructure and forward positions since 2019 has taken place near a locality called Gogra, roughly 10 kilometres northwest of the Hot Springs outposts. In April 2019 a new road was constructed to the Chinese hamlet of Wenquan, roughly 7 kilometres north of the LAC. Since then, there has been a significant military build-up along the river valley towards the LAC, with the nearest permanent Chinese position within 1.8 kilometres of the LAC.

Satellite imagery from late May shows significant developments closer to the border (map 6). From the forwardmost positions, there’s a clear dirt track that crosses almost 1 kilometre into Indian-controlled territory. There is also a second, looped dirt track that crosses nearly 500 metres into Indian-controlled territory; the fact that it’s a circular track suggests that it may be a regular patrol route. There are no PLA positions on the Indian side of the LAC; however, these tracks suggest that PLA forces are regularly making incursions into Indian territory, at a remote part of the LAC that is 10 kilometres from the nearest Indian positions.

In response to this, India has begun constructing a large, permanent position on its side of the LAC, but along the river valley in a position that overlooks the LAC, presumably to prevent any further incursions by PLA forces into Indian territory.

Map 6: Hot Springs area, showing position of developments between Gogra and Wenquan, May 2020

These developments seem to have occurred peacefully, with no media reports of skirmishes. Indian Army sources refer to the successful, but limited, disengagement of Indian and Chinese troops in the Hot Springs area. The distance between the forwardmost positions of the PLA and the Indian Army in the area is much greater than in the Galwan River Valley.

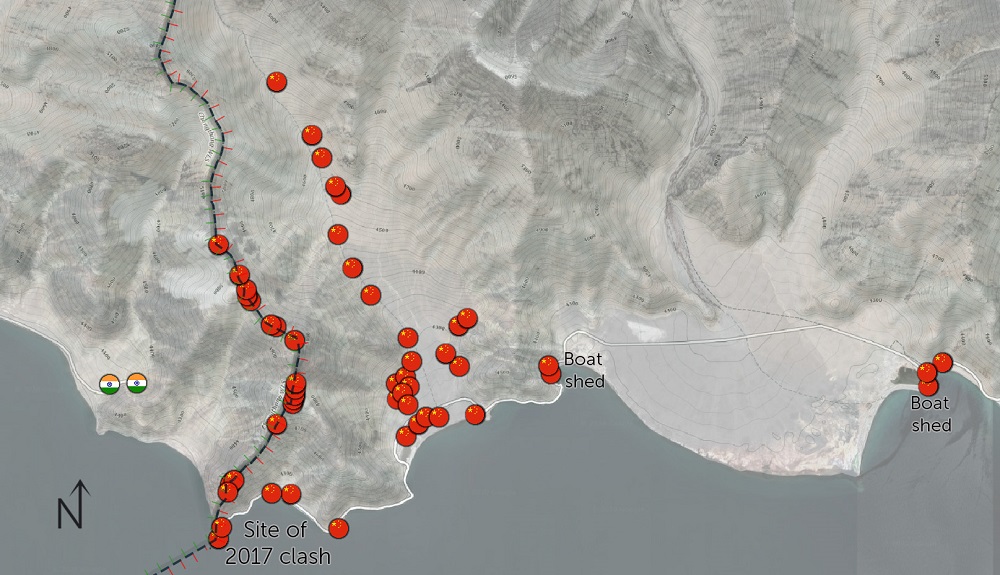

The third significant hotspot in Ladakh is the Pangong Tso, an alpine lake over 100 kilometres long that is bisected by the India–China border. This area is the site of the most significant divergence between New Delhi and Beijing on the precise location of the border, differing by up to 30 kilometres. A number of peninsulas (known as fingers) mark the named features of the lake, with China claiming territory up to finger 2, and India claiming territory up to finger 8 (map 7).

Map 7: Pangong Tso, showing Indian and Chinese positions and claims relative to Actual Line of Control

India has had permanent positions within the disputed area (between fingers 3 and 4) for at least 10 years and expanded its presence in the disputed area in 2015–16. China kept its permanently stationed forces outside of the disputed territory until May.

In the past month, Chinese forces have become an overwhelming majority in the disputed areas. Significant positions have been constructed between fingers 4 and 5, including around 500 structures, fortified trenches and a new boatshed over 20 kilometres further forward than previously. More structures appear to be under construction.

The scale and provocative nature of these new Chinese outposts is hard to overstate: 53 different forward positions have been built, including 19 that sit exactly on the ridgeline separating Indian and Chinese patrols.

In 2017, footage emerged showing a significant clash between Indian and Chinese troops at finger 4 of the lake. The beach shown in the footage has, since May, been permanently occupied by PLA troops with a garrison of around 20 structures.

A detailed view of the new Chinese positions is shown below.

Map 8: Pangong Tso, showing new Chinese positions

In all hotspots along the Ladakh sector of India’s border with China, both sides have engaged in significant efforts to build up their forces in forward positions and alter the status quo along the LAC.

This week’s deadly skirmish shows that the situation is extremely volatile and introduces the possibility of escalation along the border regions. It could act as a shock to policymakers in the region and spur them to push for more genuine and meaningful disengagement to prevent further loss of life. But it could also spark a larger confrontation between the two nuclear-armed powers that could escalate into a major conflict.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is ‘not in a good mood’, US President Donald Trump recently declared, as he offered to mediate India’s resurgent border conflict with China. After years of bending over backwards to appease China, Modi has received yet another Chinese encroachment on Indian territory. Will this be enough to persuade him to change his approach?

While India was preoccupied with the Covid-19 crisis, China was apparently planning its next attempt to change the region’s territorial status quo by force. The swift and well-coordinated incursions by People’s Liberation Army troops into the icy borderlands of India’s Ladakh region in May were likely the product of months of preparation. The PLA has now established heavily fortified camps in the areas it infiltrated, in addition to deploying weapons on its side of the Line of Actual Control, within striking distance of Indian deployments.

China’s ‘unexpected’ manoeuvre shouldn’t have been unexpected at all. Last August, China’s government vigorously condemned India’s establishment of Ladakh—including the Chinese-held Aksai Chin Plateau—as a new federal territory. (China seized Aksai Chin in the 1950s, after gobbling up Tibet, which had previously served as a buffer with India.) And the PLA had been conducting regular combat exercises near the Indian border this year.

Deception, concealment and surprise often accompany China’s use of force, and Chinese leaders have repeatedly claimed that military pre-emption was a defensive measure. Its latest assault on India—which China claims is the actual aggressor—was taken straight from this playbook.

Yet Modi didn’t see the Chinese incursions coming. His vision seems to have been clouded by the naive hope that, by appeasing China, he could reset the bilateral relationship and weaken China’s ties with Pakistan, another revisionist state that lays claims to sizeable swaths of Indian territory.

The China–Pakistan axis has long generated high security costs for India and raised the spectre of a two-front war. That’s why some Indian leaders have pursued a ‘defensive wedge strategy’, in which the status quo power seeks to drive a wedge between two allied revisionist states, so that it can focus its capabilities on the more threatening challenger.

In 1999, the first prime minister from Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, sought to win over Pakistan by visiting the country on the inaugural trip of a new bus service from Delhi to Lahore. Vajpayee was rewarded for his ‘bus diplomacy’ with a stealth invasion by Pakistan’s powerful military of the Indian border zone of Kargil. This triggered a localised war, in which both sides lost several hundred soldiers before the status quo ante was restored.

Unlike Vajpayee, Modi has focused his attention on China—with similarly disastrous results. In fact, soon after becoming prime minister in 2014—and just hours before hosting Chinese President Xi Jinping for a summit meeting—he learned that PLA troops had elbowed their way into southern Ladakh’s Chumar area, which lies along the Line of Actual Control, and built a temporary road there.

The summit was portrayed as a success, even though the Chinese didn’t withdraw until weeks later, after India agreed to demolish local defensive fortifications. This was the beginning of a policy not of reconciliation but of appeasement, the costs of which continue to mount.

On a trip to Beijing the next year, Modi surprised his own administration by announcing a decision to issue electronic tourist visas to Chinese nationals upon their arrival in India. He also delisted China as a ‘country of concern’, in an effort to court Chinese investment. Instead, the move opened India up to even more dumping by Chinese firms. On Modi’s watch, China has more than doubled its trade surplus with India to US$60 billion per year—nearly equal to India’s annual defence spending.

Meanwhile, the PLA has continued to encroach on disputed territories. In mid-2017, Indian troops were pushed into another standoff with the PLA—this time at Doklam, a small and desolate Himalayan plateau where Chinese-ruled Tibet meets the northeastern Indian state of Sikkim and the Kingdom of Bhutan. Indian troops stood up to the Chinese, as the PLA attempted to build a road to the India border through the uninhabited plateau that Bhutan, an Indian ally, regards as its own territory. The standoff lasted 73 days, before China and India agreed to disengage.

India declared the Doklam disengagement a tactical victory. But over the next several months, China steadily expanded its troop deployments by building permanent military structures, thereby gaining control of much of Doklam. Despite being the de facto guarantor of Bhutan’s security, India failed to defend the tiny country’s territorial sovereignty.

Yet Modi maintained India’s appeasement policy. In 2018, his government backed away from official contact with the Dalai Lama and Tibet’s India-based government-in-exile. At the same time, as Xi later revealed, Modi proposed an annual ‘informal’ bilateral summit—a proposal Xi gladly accepted, because high-level meetings aid China’s ‘engagement with containment’ strategy towards India. Two such summits have now been held, as well as 14 other meetings between the two leaders.

And what has Modi gotten for his troubles? China has stepped up its territorial revisionism, while raking in growing profits from the bilateral economic relationship (though, to be sure, India did recently tighten its policy on foreign direct investment, so that any flows from China must be preapproved).

Modi has himself to blame for this state of affairs. With his excessive personalisation of policy and stubborn strategic naivety, he has shown himself not as the diplomatically deft strongman he purports to be, but as a kind of Indian Neville Chamberlain. Unless he learns from his mistakes and changes his policy towards China, India’s people—and territorial sovereignty—will pay the price.

As tensions on the border between India and China have once again lit up, so too has anti-Beijing sentiment among Indians. Calls to boycott Chinese products have precedents in India, and this time Hindu nationalists are uniting against the Chinese-owned short-video streaming platform TikTok.

TikTok has gained immense global popularity since its launch in 2017 and is now the most downloaded social media app in the world, overtaking Facebook and YouTube, with 2 billion downloads as of April. The app has 800 million active users and its target audience is relatively young—most are aged between 16 and 24.

The app has a Chinese version called Douyin, which is available only in mainland China. The international version is not accessible to Chinese citizens.

India is now TikTok’s biggest market, where it’s reached 611 million downloads—a third of its total downloads worldwide. However, the app is also reported to have triggered murders and scandals, with clashes between different castes and religious and social groups that have resulted in accusations of racism, sexism, colourism and various other forms of targeted discrimination.

TikTok, as well as its parent company ByteDance, also remain under severe scrutiny in the West. American and European lawmakers and NGOs have voiced concerns over privacy, data storage, child protection and political censorship. In one case, a video posted by an American teenager who called out China’s treatment of Uyghurs was taken down and later reinstated after an international backlash.

Over the past three weeks there’s been a news storm in India about highly controversial videos published by famous users that caused significant outrage among celebrities, members of parliament and citizens.

The videos showed violence against women, animal abuse, pandemic-related fake news, and other such content. One viral video mimicked an acid attack on a woman. While TikTok responded to the public outcry by deleting videos and banning some of their authors, the most prominent of which was TikTok celebrity Faisal Siddiqui, people have criticised the company for reacting too slowly, and for allowing similar videos to remain on the platform.

Local media outlets have reported on many examples, including allegations that TikTok directed its employees in India to censor content related to Tibet and the Dalai Lama. That claim has not been verified.

#BanTikTokIndia and other related hashtags trended on Twitter throughout May as users took to different platforms. Some activists have also started an online petition urging that moderation of TikTok’s content be made stricter. It now has more than 80,000 signatures.

TikTok had been banned from the country in April 2019 due to concerns related to pornography, child abuse and paedophilia. ByteDance responded promptly by implementing more rigorous regulations and community guidelines and it was reinstated after two weeks.

This time, however, overcoming public disdain will likely prove more difficult, as activists seize this opportunity to build up an anti-TikTok protest online.

Large statutory bodies, such as the National Commission for Women and the High Court of Orissa, have called on the government to regulate the app. While no official decision has yet been made, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has announced a push for local products under the slogan ‘Vocal for Local’.

This move has indirectly affected TikTok, as it called on netizens to favour local tech products over their Chinese counterparts, and it prompted the popularity boom of an app called ‘Remove China Apps’, which scans users’ phones and deletes any Chinese applications. It was downloaded more than 5 million times before it was pulled from the Google Play store.

The current wave of criticism has also prompted people to leave negative reviews of TikTok online and on multiple online app stores. TikTok’s listing on Indian Google Play recently saw a rapid decline in ratings from 4.5 to 1.3 stars in one day. Google, however, has since deleted millions of reviews after detecting malicious activity by critics who appeared to have set up fake accounts.

Amid the legitimate calls for censorship of videos that seek to justify or encourage violence against women, for example, some Indian nationalists are taking advantage of the momentum to urge bans of videos that criticise the country’s government.

An Indian woman in Canada posted a TikTok video using the Indian national anthem to criticise Hindu nationalists and Modi. The video went viral and sparked rage, with calls for authorities to intervene, for TikTok to take the video down and ban the user, and for the Indian government to fully ban the app.

People filed reports and flagged the video, but TikTok is yet to comment.

The woman who posted the video has been the victim of online attacks and people have demanded that Indian authorities seek her arrest for insulting the national anthem.

These controversies are not good for business. The Indian market provides TikTok with more than US$3.3 million in revenue per quarter and another official ban would be a big blow to the company.

While TikTok’s leadership has so far ridden out the storm of public outrage, it will be interesting to see how, or whether, the app survives the #BanTikTokIndia outcry.

Many local factors have contributed to the face-off between Indian and Chinese forces in Ladakh.

Western Ladakh borders Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, Gilgit and Baltistan, where China has invested hugely its economic corridor project with Pakistan under the Belt and Road Initiative. China’s apprehension about Indian designs on the territory has been accentuated by recent comments by Indian leaders, including External Affairs Minister Jaishankar, that India expects to have ‘physical jurisdiction’ over it ‘one day’.

Ladakh also borders Tibet and Xinjiang, the turbulent peripheries of China, and Beijing is apprehensive of Indian moves supported by the US that may threaten its control over these regions.

The trigger for the current face-off was China’s opposition to India’s laying a key road in the finger area around Pangong Lake and constructing another connecting Darbuk–Shayok–Daulat Beg Oldie road in Galwan Valley. China is also laying a road in the finger area, which India finds objectionable. According to Indian sources, China has deployed 5,000 heavily armed additional troops to the area and India has responded in kind. Both militaries have also moved in heavy equipment and weaponry, including artillery and combat vehicles, to their rear bases close to the disputed areas in eastern Ladakh.

Indian and Chinese forces in Ladakh are separated on the basis of a Line of Actual Control, drawn at the end of the 1962 war but still contested in some areas. India argues that Chinese forces have violated this arrangement. Bilateral moves at the military and diplomatic levels are on to defuse the situation, but both sides have rejected US President Donald Trump’s offer to mediate the dispute.

However, most observers believe that not only local factors have led to China’s move in Ladakh. Beijing is feeling increasingly beleaguered globally and regionally and has embarked on a strategy with several goals. It assumes that foreign adventurism cloaked in the garb of ultranationalism can shore up the Chinese Communist Party’s rule at home. While the authoritarian regime’s legitimacy rests primarily on its economic performance, it is now facing the prospect of a severe decline in the country’s GDP.

Simultaneously, creating a crisis with neighbours can divert international opprobrium at a time when China is facing heavy criticism, including from Australia, because of its failure to notify the world of the coronavirus during the crucial early weeks when it could have been more easily contained.

In the face of such criticism, the Chinese regime is increasingly using jingoistic jargon to build up domestic support. In a recent speech, President Xi Jinping exhorted the armed forces to ‘prepare for war’ in order to ‘resolutely safeguard national sovereignty’ and ‘the overall strategic stability of the country’.

China’s relations with the US have been going downhill since soon after Trump was elected, which has unnerved Chinese leaders despite their disclaimers. Trade disputes have led to repeated threats by Trump that he would unleash a trade war against China. Beijing has deliberately eroded Hong Kong’s special status and is suppressing its pro-democracy movement, leading to much criticism from the US administration and in Congress. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has told Congress that Hong Kong is no longer autonomous from China and no longer merits special treatment under US law.

Differences over Taiwan have added to US–China tensions. The CCP sees Taiwan as a breakaway province and it considers the US to be the primary impediment to the island’s integration with China. The Trump administration has significantly increased American support to Taiwan with arms sales and laws, such as the Taiwan Allies International Protection and Enhancement Initiative (TAIPEI) Act to help Taiwan deal with pressure from China. In response, China has stepped up its military activity around Taiwan, further accentuating the tensions.

Above all, US–China rivalry in the South China Sea appears to be the most serious potential flash point that could start a conflagration. Over the past decade, China has vigorously advanced its territorial claims there by militarising islands it controls and vociferously contesting claims by other states and impeding their attempts to access territories that they claim.

So far China has acted cautiously to prevent these moves from triggering a serious confrontation with the US, but that might change if it feels under greater pressure internationally.

Washington has a strong interest in preventing Beijing from asserting control over the South China Sea, as maintaining free and open access to this waterway is important to the US for economic reasons. It also has defence treaty obligations to the Philippines, which has been in the forefront of contesting Chinese claims. For China, the ability to control the South China Sea would be a major step in threatening the US position as the foremost power in the Indo-Pacific region.

Increased Chinese adventurism born out of its inability to respond adequately to external criticism and to control domestic discontent could result in an escalation of US–China tensions in the South China Sea.

If that happens, the India–China confrontation over road building and movement of troops close to the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh could become a sideshow in a much larger ‘great game’ played out in Asia between the US and China.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s penchant for theatrics has had deadly consequences for India’s poor. That was certainly the case with his disastrous demonetisation policy in 2016 and his government’s rushed implementation of a national goods and services tax, which resulted in widespread harassment of small businesses.

But these flubs were merely the opening act. By imposing one of the world’s harshest Covid-19 lockdowns before preparing adequately or consulting with lower levels of government, Modi has inflicted unprecedented damage on India’s economy and on the poor, who live hand-to-mouth at the best of times. According to some estimates, more than 120 million people lost their jobs and incomes immediately after the lockdown was ordered on 24 March. And about half of the country’s population of 1.38 billion is likely to have been impoverished, with many approaching starvation levels.

Shortly after the lockdown started, India’s finance minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, announced a relief package amounting to less than 0.5% of GDP. The program consists primarily of extra food rations, and merely front-loads pre-existing small income grants for farmers, while offering a pittance in cash assistance for women with bank accounts tied to the government’s financial inclusion program. Survey data suggest that only about half of India’s poor women have such accounts.

Then, after seven excruciating weeks, Modi announced with great fanfare on 12 May that his government would adopt a rescue package worth 10% of GDP. But while this sounds much better than what came before, a closer examination reveals that the amount of immediate relief for the poor remains minimal. That ‘10% of GDP’ includes all the liquidity enhancements announced over the previous three months by the Reserve Bank of India. Worse, most of these funds remain unused, because banks have been unwilling to lend them on to private-sector firms.

The banking sector’s stance is understandable. It has been obvious for years that India’s economy suffers from deficient demand, which is why it was in a prolonged slowdown before the pandemic arrived. Now that the lockdown is inflicting deep economic losses, an increase in bank lending would most likely do little more than add to the stock of bad loans.

The latest rescue package includes a credit guarantee (not actual loans) for 4.5 million microenterprises and small and medium-size businesses (out of a total of 63.4 million). It also includes working-capital assistance for farmers and street vendors, and a budget increase for rural public works. But while these measures could help to restart disrupted production and supply chains, they won’t solve the staggering demand problem.

After weeks of callous disregard for the plight of tens of millions of migrant workers, the government has now announced two months of grain rations. These workers have been hungry and homeless since suddenly losing their jobs, and, with public transportation locked down, many had no choice but to walk hundreds of kilometres with luggage and children to their villages. Hundreds died on the way.

In general, the government’s response has largely excluded hundreds of millions of daily wage labourers and urban workers. A substantial increase in cash assistance to all these people—with or without bank accounts—would have gone a long way towards boosting demand. Likewise, the government could have done more to discourage major non-farm employers from shedding their workforces, such as by offering a significant wage subsidy for workers on their payrolls (as many other countries, both rich and poor, have done).

The Modi government has also ignored the pressing need for a large-scale transfer of central funds to near-bankrupt state governments that have been covering most of the spending on healthcare, agriculture and social protections, and have little capacity to borrow at low cost. Instead, the government’s decision-making remains over-centralised, with little participation by local governments and communities, resulting in confusing and conflicting administrative rules.

In a country with a chronically underfunded health system, the immediate priority should have been to invest in a massive public health program, particularly at the primary-care level. A government focusing on what really matters would have launched a decentralised program for testing, contact tracing and quarantine, while providing special protections for vulnerable populations. This would have allowed for a cautious early relaxation of the lockdown for the rest of the population, who could have returned to earning a living.

Weighed against the scale of the looming disaster, the government’s fiscal response has been pitiably small, still amounting to a mere 1% of GDP or so. Modi and his advisers are probably worried about the government’s perceived fiscal rectitude in the eyes of the credit-ratings agencies. But not even a high credit rating will stop—let alone reverse—the capital flight currently gripping India; a fiscal chastity belt at a time of economic collapse and widespread destitution is unlikely to help.

Of course, in the medium term, the bill for a larger rescue program must be paid. That would be painful—but not impossible—with the help of public borrowing, a drastic reduction in subsidies for the better off, and a significant increase in taxation. Given that India taxes neither wealth nor inheritance and under-taxes capital gains and real property, plenty of untapped revenue sources are available. A ‘corona levy’ towards an overhaul of the country’s health system would also be timely. Needless to say, vested interests will vehemently oppose any new taxes. But there is no better time than a crisis to overcome such resistance.

The great political paradox of contemporary India is that despite all the hardships that Modi has visited upon the poor, he retains considerable popularity among them. A significant portion of the electorate seems to have bought into his fiery rhetoric of muscular Hindu nationalism, and he certainly hasn’t been hurt by the opposition’s fecklessness. In February and March—crucial weeks for pandemic preparation—Modi’s party was busy spewing hatred against minorities and dissenters.

It’s hard to accept that Modi’s popularity will remain untarnished by the problems arising from his mismanagement of the Covid-19 crisis. But if the past is a reliable guide, his hammy bravery against the virus and other elusive enemies may continue to work for him politically, even as it leaves tens of millions of Indians worse off.