Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

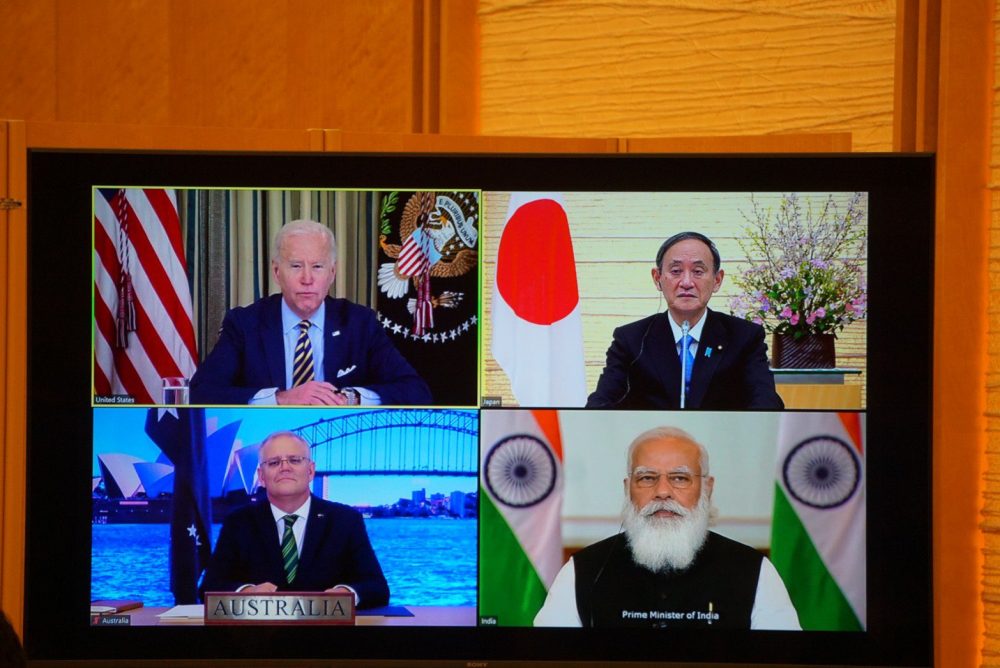

Prime Minister Scott Morrison may be forecasting ‘a new dawn in the Indo-Pacific’ with the arrival of the Quad meeting of Australian, Japanese, Indian and US leaders, but we would do well to remember the village folklore that ‘the darkest hour is just before the dawn’.

The Quad has a strategic mountain to climb to bolster faltering democracies in our region, to stop Covid-19 scything through countries that are ill-equipped to respond and, above all, to push back against the predatory wolf warriors of Beijing.

While Morrison was rightly putting a positive cast on the meeting, his Quad opening comments compared our current situation to a century ago when, after the last global pandemic, the world ‘soon found a Great Depression and another global conflict’.

The risk of a slide into conflict is clearly playing on the prime minister’s mind. Releasing a defence strategic update in July last year, Morrison said: ‘That period of the 1930s has been something I have been revisiting on a very regular basis, and when you connect both the economic challenges and the global uncertainty, it can be very haunting.’

The Quad is a grouping of countries each of which, for different reasons, is reluctantly pressed to the Indo-Pacific strategic frontline. President Joe Biden’s emphasis on working with the allies means that the US, the world’s security provider of choice, is tired of the burden and wants others to take some of the load.

Of the other Quad countries, India is only just emerging from its non-aligned mindset and beginning to craft a world view that looks beyond its immediate borders. Japan’s ‘peace constitution’, and an assumed deep public aversion to military conflict, limits Tokyo’s capacity for forthright strategic leadership.

And Australia? We have long talked a big game of ‘punching above our weight’ but baulk at the cost of real strategic leadership, even with the Pacific islands, let alone the 650 million people of Southeast Asia. Morrison promised his Quad colleagues that ‘we’ll do our share of the heavy lifting to lighten the burden for us all’. Only so much heavy lifting can be done with defence spending at 2.19% of GDP, overseas development assistance at $4 billion and falling (prior to Covid-19) and one of the smallest diplomatic corps among G20 countries.

The Quad’s arrival as a vehicle for the heads of government to meet regularly, including face to face before the end of 2021, is a substantial development, but the context is that the region has singularly failed to provide driving strategic leadership in recent years. The most important thing the new grouping can do is for the leaders to spur each other on to bigger, more imaginative policy efforts and not be slowed by bureaucratic process.

The leaders established three groups to work on urgent tasks. The Quad vaccine partnership seeks to expand vaccine manufacturing and deliver inoculations through the region, crucially to the ‘last mile’ for ‘hard-to-reach communities in need’.

Australia signed up to be a ‘last-mile’ deliverer in Southeast Asia, having already agreed to play that role in Timor-Leste and nine Pacific island states. This is vital work, but we should have no illusions about the scale of the task involved.

If Canberra is seriously going to tackle last-mile vaccine delivery through Southeast Asia, this could absorb every Australian Defence Force aircraft, ship and unit, along with much of Virgin Australia and Qantas. Recall how stretched Defence was in the early 2000s to maintain a ‘brigade-plus’ formation of several thousand personnel in Timor-Leste to stabilise a country of (then) less than a million people.

There will be many ways to deliver vaccines including using private contractors and volunteer non-government organisations, but when it comes to hard-to-reach communities—consider the Papua New Guinea Highlands and Bougainville—it’s hard to see how Defence won’t be deeply involved.

Australia limited its involvement on paper to an offer of $100 million (US$77 million) for provision of vaccines, yet another example of the low-cost leadership of which we are so nationally fond. Does this in any way meet the scale of the problem?

Even before vaccines are distributed, we may face an immediate Covid-19 crisis in PNG, where Port Moresby’s tiny hospital resources have been swamped. It might not have been possible to know when the pandemic would hit PNG, but it was surely predictable that it would arrive sometime.

The government has now announced assistance in the form of vaccine doses, medical teams and protective equipment, though more help may be needed to bring the situation in PNG under control.

Throughout the developing world during the pandemic Beijing continued to send its political leaders, diplomats, aid workers and others at a time when our travel was constrained. This was clearly a tactic to build Chinese Communist Party influence at our expense. The Quad vaccine strategy demands that we urgently get back into the region.

A Quad climate working group and a critical and emerging technology working group were also established. The former was clearly the price of America admitting the others to the call and well worth paying if it keeps Biden committed to the harder end of security engagement in the Indo-Pacific.

The critical and emerging technology group will bring the Quad most openly into competition with China because of the urgent need to develop technology options that don’t involve building dependence on Beijing or being vulnerable to yet more intellectual property cyber theft from China.

The importance of the Quad is that it holds open the possibility that Washington will include the allies as part of critical supply chains. Australia’s interest in domestic production of air- and ship-launched missiles is much more achievable if we make it part of an international effort of key democracies.

The arrival of the Quad leaders’ meeting shows not just that a consensus has emerged about our dire strategic situation but also that we desperately need to do something about it quickly, not in defence acquisition timeframes measured in decades.

Covid was the lead topic of this meeting, but the four leaders would probably not have met if the pandemic had been the only driving factor. This meeting happened for one reason only: the aggressive and destabilising behaviour of Xi Jinping. Beijing might contemplate that as it tweets out its dismissive contempt for the gathering.

‘We strive for a region that is free, open, inclusive, healthy, anchored by democratic values, and unconstrained by coercion.’

— Quad leaders’ joint statement, ‘The spirit of the Quad’, 13 March 2021

The leaders’ meeting of Quadrilateral Security Dialogue partners Australia, India, Japan and the United States is a potent promise, a sparkling moment for the reborn ‘democratic security diamond’.

The Quad mission ranges from vaccines on land to vessels at sea: finance, manufacture and distribute one billion doses of Covid-19 vaccines across Asia by the end of 2022; ‘meet challenges to the maritime order in the East and South China Seas’.

Four disparate democracies can do much together, not least to reassure Southeast Asia that it has agency and options (Quad-speak: ‘strong support for ASEAN’s unity and centrality’).

The ambit and arc of the Quad’s ambitions can mess with Beijing’s mind. Given all the hurt China has been dishing, what’s not to like?

The Quad leaders’ statement talks about responding to Covid-19 and climate change, and addressing ‘shared challenges’ in cyber space, critical technologies and counterterrorism. Then there’s the biggest ‘C’ of all, an emphatic presence even when not mentioned. The irony is that China is the godfather of Quad 2.0. The four democracies are present at the creation, but conception came from China’s coercion.

Australia walked away from Quad 1.0 in 2008 because we had high hopes about China and doubts about Japan and India; Canberra bet on Beijing rather than Tokyo and New Delhi. Now the race has changed dramatically, the stakes are even higher, and Australia puts new wagers on Japan and India to reinforce its traditional bet on the US.

Quad 1.0 sunk, Kevin Rudd says, because the US and India weren’t keen, and neither was Japan after Shinzo Abe departed from his first term as Japan’s prime minister in 2007. Quad 2.0 arrived, Rudd notes, because Xi Jinping has ‘fundamentally altered the landscape’ by projecting Chinese power, and strategic circumstances have ‘changed profoundly’.

The mission of Quad 2.0 becomes more than patrolling the Indo-Pacific—the ambit of Quad ambition meets today’s angst and ambiguity.

Returning as Japan’s prime minister in 2012, Abe began work on the Quad’s second coming, describing it as a ‘democratic security diamond’ that would be all about the maritime domain. Abe’s diamond image was based on ‘a strategy whereby Australia, India, Japan, and the US state of Hawaii form a diamond to safeguard the maritime commons stretching from the Indian Ocean region to the western Pacific’.

The logic of the democracy diamond today is to outplay and outweigh a China that the US describes as an assertive competitor, ‘combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system’.

Australia, India, Japan and the US are being driven together as much as they’re naturally coming together. A new cohesion is shown by the simple fact that the three prime ministers and the president issued a joint statement from their summit; previously, when the Quad foreign ministers met, each country gave a separate written account of the talks.

The summit statement on ‘the spirit of the Quad’ offers lots of sparkling facets. The outcomes fact sheet pins detail to the ambition, with a Quad vaccine partnership and vaccine experts group; a climate working group; and a critical and emerging technology group on standards, telecommunications, biotechnology and supply chains. The contests will happen in labs and factories as well as on the far seas.

As an aside on the internal battles of Australia’s Liberal–National coalition government, the Quad statement about climate change (‘a global priority’) marks another step in Scott Morrison’s delicate effort to herd his fractious flock up the path to the UN climate conference in November.

From domestic politics to geopolitics, the game is on the move.

For the Biden administration, the Quad puts an exclamation point on the shout that the US is back. The democracy diamond demonstrates America’s chameleon skill in Asia: the ability to do formal alliances (Australia, Japan and South Korea), de facto alliances (Singapore and Taiwan) and partial or quasi-military relationships (Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam). The Quad demonstrates India’s slow, firming shift to become a de facto US ally. The US military says what’s being built with India can be the ‘defining partnership of the 21st century’.

Ever seeking to anchor the US in Asia, Canberra and Tokyo now have another anchor point in New Delhi. The anchor image responds to a permanent reality: China will always be in Asia, while the US presence is always a choice Washington makes.

Choosing the Quad, the US is renewing its promise to the Indo-Pacific as much as it’s joining with three fellow democracies.

The head of US Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral Philip Davidson, says ‘the diamond of democracies’ can build into something bigger: ‘Not in terms of security alone, but in terms of how we might approach … the global economy, critical technologies like telecommunications and 5G, collaboration on the international order—just much to be done diplomatically and economically.’

The Quad isn’t an alliance. The Indo-Pacific democratic diamond won’t match the four-pointed NATO star. The outlook of the Quad members is as different as their democracies (note the time-zone differences, stretching across the date line, in conducting the virtual summit of the four leaders).

US military flexibility—that chameleon ability—means the Quad rests on its alliances with Australia and Japan and the de facto alliance forming with India.

As Michael Green observes from Washington:

In military terms, the US–Japanese–Australian trio is far more interoperable than the four are together, though the recent resumption of joint naval exercises will help. The Quad will be one part of a variable geometry of alliances and diplomacy in Asia. After this summit, it will now clearly be one of the most important parts.

Indo-Pacific maritime security is the ‘one issue that makes the Quad the Quad’, Salvatore Babones argues:

The Quad is never going to go to war with China. In any case, treaty alliances and military procurement partnerships are more effective tools for preventing war than a loose international grouping. What the Quad can do is provide a backbone for broad Indo-Pacific maritime security cooperation that tamps down China’s brinkmanship across the region.

The Quad will feed into US musings about reforming the 1st Fleet, last on station in the Pacific in 1973, to increase its naval presence in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. The 1st Fleet could be headquartered in Singapore and/or Western Australia. (After the lengthy wrestle about paying for US Marine Corps facilities in Darwin, Canberra is match-tough to grapple with the Pentagon over the dollars.)

Not so long ago, a bigger US presence in the ocean India calls its own would have produced howls from New Delhi. Now such a build-up would fit with India’s hardening strategic understanding of China’s hegemony vision, and the maritime dimensions of the Quad mission.

As diamonds are formed by high temperature and pressure, so the Quad bonds four democratic powers that feel the force and weight of Asia’s coming power.

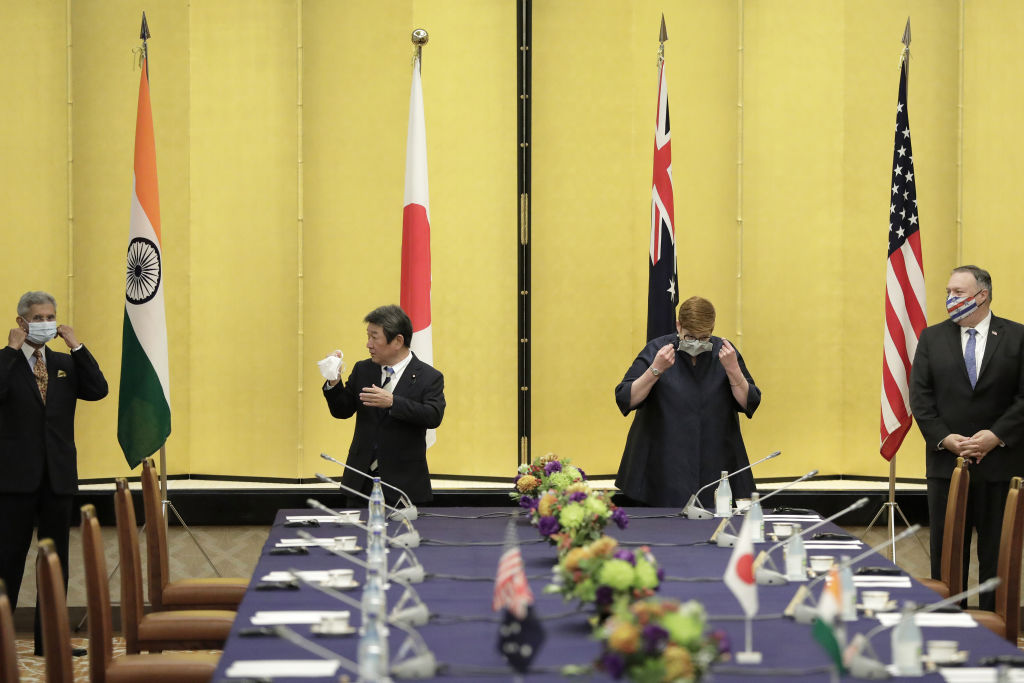

Four years ago, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue was something only officials, not ministers, could engage in and there were studious denials that the grouping had anything to do with China’s use of power and economic coercion. Official statements were bland and actions were few.

Since then, things that simply couldn’t happen according to received wisdom have kept happening. The Quad moved from a forum just for officials to a foreign ministers’ forum in late 2019. Last year, India’s Malabar naval exercise broadened to include Australia, making it a key naval exercise for the four Quad partners. And more foreign ministers’ meetings have been held since that start in 2019. This is now an agreed ‘forum architecture’, so beloved of students of international security forums and institutions.

The biggest development has happened at speed under the new US administration. President Joe Biden used his first call with Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping to give priority to ‘preserving a free and open Indo-Pacific’—a concise statement of what the Quad is all about. And now, just two months later, he and the prime ministers of India, Japan and Australia are getting ready for a Quad leaders’ meeting on Friday morning, Washington time.

This is happening because the Quad is a grouping that makes more and more sense as the strategic environment in the Indo-Pacific develops.

The momentum for India, Japan, the US and Australia to cooperate on security, economics, technology and public health comes partly from global interconnections, and partly from the converging assessments each nation is making about the behaviour and actions of China under Xi.

The leaders are driven by Chinese actions—that familiar list of military aggression in the South and East China Seas, around Taiwan and on the India–China border; acute human rights abuses in Xinjiang, Hong Kong and Tibet; and economic coercion, cyber hacking and political interference in other nations, combined with the expulsion or arbitrary detention of foreign nationals. Add in Beijing’s continued failure to be transparent about either the origins of the pandemic or the efficacy and safety of Chinese Covid-19 vaccines.

But Narendra Modi, Yoshihide Suga, Scott Morrison and Biden are also responding to very strong public sentiment in each of their countries.

This is a symptom of China’s soft power collapsing across much of the world.

That’s shown in a deluge of surveys, including the October Pew Research survey showing unfavourable views of China at historic highs across the developed world, Singapore’s ISEAS think tank’s February ‘State of the region 2021’ survey showing even higher concern about China ‘not doing the right thing’ after the experience of 2020, and the most recent Pew assessment of views in the US on China, released last week.

These surveys tell us that populations across the Indo-Pacific, in Europe, North America and Australia, are ahead of their governments—and certainly many in their business communities—in appreciating the implications for their security, wellbeing and prosperity of the way China is behaving and acting under Xi.

Beijing almost certainly discounts these populations’ views. As we see with the National People’s Congress, the Chinese government is advancing its strategy for growing and using power and influence through a combination of hard power, the attraction of making money from China’s large market and a plan to dominate the sources of future technological and economic power. That’s enabled by a supportive network of advocates in the political, business and academic elites of other nations, which Australian journalist Rowan Callick has described well in his recent paper for the Centre for Independent Studies, The elite embrace.

Domestically, the CCP is adept at controlling and directing public sentiment, using its own elites, security agencies and, increasingly, high-technology surveillance and social media management. So maybe it’s simply assuming that keeping foreign elites onboard will be enough to enable the continued pursuit of its ‘China dream’ of a Sino-centred world, with China under continued party-centred control.

That assumption misunderstands how much of the rest of the world works. Governments in India, the US, Japan and Australia must respond to their populations, in ways that China’s autocrats can’t get to grips with.

We are a world away from 2007, when furious diplomatic démarches from Beijing resulted in officials quickly disowning the idea that the Quad would do anything meaningful.

Quad leaders now know that actions they take that reduce the influence of aggressive Chinese power will be welcomed and rewarded domestically. And a practical agenda for the Quad that has this effect also, conveniently, can address some core policy directions of each of the leaders. It’s not often that a multilateral grouping can so effectively combine national and joint interests.

Look at the agenda for Biden, Morrison, Suga and Modi: accelerating vaccine production and rollout, finding practical approaches to increase economic cooperation in ways that reduce supply-chain vulnerabilities, and identifying common actions on climate change that have the by-product of advancing the economies and high-tech industries in each of our countries.

Each of these topics is a net good for each of our leaders, and each is given energy and urgency by China’s actions over recent years, and in the new five-year plan that’s now being signed off by the National People’s Congress.

The combined weight of the Quad partners can be a defining good, achieving multilaterally what each nation couldn’t alone—an idea at the heart of Biden’s interim national security guidance.

Vaccine production and rollout is an example. The US has developed what open scientific data tells us are some of the safest, most effective Covid-19 vaccines—the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is a single-dose shot, for example, reducing the scale and challenge of mass vaccinations. India, as a medicines-production superpower, has the horsepower to make these at speed and scale. And the combined financial and logistical capacity of the Quad partners, along with their strong relationships across South and Southeast Asia all add up to a package that will make a difference to the safety and wellbeing of a major chunk of the globe. Progress here works directly with Morrison’s South Pacific step-up, and with each of the partners’ Indo-Pacific strategies.

The Quad forum is not the sum of all things, although it is complementary to other groupings that also have a role in enhancing positive cooperation that reduces nations’ vulnerabilities, whether to pandemics or coercion. The G-7 and the Five Eyes come to mind, as do NATO, a renewed EU–US partnership and a revitalised US alliance network.

However, the Quad is developing as a working forum for leaders to generate momentum on practical actions. Having to cooperate without all the traditional sherpas, summitry and bureaucracy of other forums is one of the defining positive effects that Covid has brought us.

The Quad is now much broader than the ‘security dialogue’ that restarted in 2017, and its utility will increase given the world we are living in. This may be what Beijing is most anxious about—a multilateral grouping that is action oriented and agile enough to provide new challenges to how China wants the world to work.

For all the reasons that Beijing desperately wants the Quad to fail, it is in our interests to have it grow, prosper and demonstrate its own positive agenda.

Emboldened by its cost-free expansion in the South China Sea, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s regime has stepped up efforts to replicate that model in the Himalayas. In particular, China is aggressively building many new villages in disputed borderlands to extend or consolidate its control over strategically important areas that India, Bhutan and Nepal maintain fall within their national boundaries.

Underscoring the strategic implications of China’s drive to populate these desolate, uninhabited border areas is its major build-up of new military facilities there. The new installations range from electronic-warfare stations and air-defence sites to underground ammunition depots.

China’s militarised village-building spree has renewed the regional spotlight on Xi’s expansionist strategy at a time when, despite a recent disengagement in one area, tens of thousands of its troops remain locked in multiple standoffs with Indian forces. Recurrent skirmishing began last May after India discovered to its alarm that Chinese forces had stealthily occupied mountaintops and other strategic vantage points in its northernmost Ladakh borderlands.

China’s newly built border villages in the Himalayas are the equivalent of its artificially created islands in the South China Sea, whose geopolitical map Xi’s regime has redrawn without firing a shot. Xi’s regime advanced its South China Sea expansionism through asymmetrical or hybrid warfare, waged below the threshold of overt armed conflict. This approach blends conventional and irregular tactics with small incremental territorial encroachments (or ‘salami slicing’), psychological manipulation, disinformation, lawfare, and coercive diplomacy.

Now China is applying that playbook in the Himalayan borderlands. The Hong Kong–based South China Morning Post, citing a Chinese government document, recently reported that China intends to build 624 border villages in disputed Himalayan areas. In the name of ‘poverty alleviation’, the Chinese Communist Party is callously uprooting Tibetan nomads and forcing them to settle in artificial new border villages in isolated, high-altitude areas. The CCP has also sent ethnic Han Chinese party members to such villages to serve as resident overseers.

Creating a dispute where none previously existed is usually China’s first step toward asserting a territorial claim, before it furtively tries to seize the coveted area. Xi’s regime frequently uses civilian militias in the vanguard of such a strategy.

So, just as China has employed flotillas of coastguard-backed civilian fishing boats for expansionist forays in the South and East China Seas, it has been sending herders and graziers ahead of regular army troops into desolate Himalayan border areas to foment disputes and then assert control. Such an approach has enabled it to nibble away at Himalayan territories, one pasture at a time.

In international law, a territorial claim must be based on continuous and peaceful exercise of sovereignty over the territory concerned. Until now, China’s Himalayan claims have been anchored in a ‘might makes right’ approach that seeks to extend its annexation of Tibet to neighbouring countries’ borderlands. By building new border villages and relocating people there, China can now invoke international law in support of its claims. Effective control is an essential condition of a strong territorial claim in international law. Armed patrols don’t prove effective control, but settlements do.

The speed and stealth with which China has been changing the facts on the ground in the Himalayas, with little regard for the geopolitical fallout, also reflects other considerations. Border villages, for example, will constrain the opposing military’s use of force while aiding Chinese intelligence gathering and cross-frontier operations.

Satellite images show how rapidly such villages have sprouted up, along with extensive new roads and military facilities. The Chinese government recently justified constructing a new village inside the sprawling Indian border state of Arunachal Pradesh by saying it ‘never recognised’ Indian sovereignty over that region. And China’s territorial encroachments have not spared one of the world’s smallest countries, Bhutan, or even Nepal, which has a pro-China communist government.

China conceived its border-village program after Xi called on Tibetan herdsmen in 2017 to settle in frontier areas and ‘become guardians of Chinese territory.’ Xi said in his appeal that, ‘without peace in the territory, there will be no peaceful lives for millions of families.’ But Xi’s ‘poverty alleviation’ program in Tibet, which has steadily gained momentum since 2019, has centred on cynically relocating the poor to neighbouring countries’ territories.

The echoes of China’s maritime expansionism extend to the Himalayan environment. Xi’s island building in the South China Sea has ‘caused severe harm to the coral reef environment,’ according to an international arbitral tribunal. Likewise, China’s construction of villages and military facilities in the borderlands threatens to wreak havoc on the ecologically fragile Himalayas, which are the source of Asia’s great rivers. Environmental damage is already apparent on the once-pristine Doklam Plateau, claimed by Bhutan, which China has transformed into a heavily militarised zone since seizing it in 2017.

Indian army chief Manoj Naravane recently claimed that China’s salami-slicing tactics ‘will not work.’ Yet even an important military power like India is struggling to find effective ways to counter China’s territorial aggrandisement along one of the world’s most inhospitable and treacherous borders.

China’s bulletless aggression—based on using military-backed civilians to create new facts on the ground—makes defence challenging, because it must be countered without resorting to open combat. Although India has responded with heavy military deployments, Chinese forces remain in control of most of the areas they seized nearly a year ago. So far, China’s strategy is proving just as effective on land as it has been at sea.

The balance of power in the Indian Ocean is undergoing a significant change as countries from outside the region begin to establish a permanent presence there.

In the past 10 years, the biggest change has been the sharp escalation in China’s naval activities in the northern Indian Ocean, including through its hydrographic surveys in the exclusive economic zones of littoral states, growing deployment of submarines and unmanned underwater drones, and establishment of its first overseas military facility in Djibouti.

If this is the beginning of a larger Chinese naval presence throughout the Indian Ocean, a close examination of China’s intentions and behaviour is warranted.

China claims that its naval activities are normal and reasonable and assures the rest of the world that it will never seek hegemony.

When the Chinese say that they will not exercise hegemony, they presumably mean not the American kind. They are not seeking to assume the role of a paramount state that uses its power and influence to impose rules and order on an otherwise anarchic world. Pax Britannica is not for them either. They have shown no appetite to directly control large tracts outside the homeland or to carry the flag, as David Livingstone did, for ‘Christianity, commerce and civilization’.

Exercising the sort of hegemony that the Soviet Union did is entirely ruled out. The lessons of Soviet failure due to overreach in the export of communism globally are compulsory reading for all members of the Chinese Communist Party.

What China seeks is the pursuit of national self-interest through persistent and consistent actions to become the dominant state in the Indo-Pacific. The shape of possible Chinese hegemony may be uniquely Chinese in character—a kind of Chinese hegemony with socialist characteristics. Covid-19 has made this more, rather than less, likely for three reasons.

First, the fundamental shift in the world’s centre of gravity from the Atlantic–Mediterranean region to the Indo-Pacific region has occurred faster than the West had planned for. China is the central actor in this drama, but ASEAN, India and others have also hastened the process.

Second, expectations from a decade ago that the balance of power between China and the United States would likely remain decisively in America’s favour at least for the first half of this century are being proved wrong.

China has not only demonstrated the determination to challenge American power in the Indo-Pacific, but it is building the capacity to neutralise America’s naval superiority in the Western Pacific. It is unlikely that China can, any longer, be confined within the first and second island chains in the Pacific.

Third, it is building a parallel universe in trade, technology and finance that will selectively reduce its vulnerabilities to American hegemony. China’s international behaviour in the year of Covid-19 gives legitimate cause for concern to the peripheral and proximate states of the Indo-Pacific.

China speaks of the ‘community of the shared future for mankind’, and ‘win–win cooperation’; it plays balance-of-power politics and acts in ways that take advantage of others in adversity. China’s aim is to establish its supremacy in areas of productive technology, trade networks and financing options in ways that shut out competition. The Belt and Road Initiative is creating a Sino-centric system of specifications, standards, norms and regulations that will favour China’s technology and services to the exclusion of others.

Those who worry that the primary problem with the BRI is the potentially high level of indebtedness that vulnerable Indo-Pacific economies may face are missing the larger point. Beijing doesn’t aim to impoverish its potential clients, but to ensure that their national systems are fully oriented towards the consumption of Chinese technology and services and are in sync with China’s strategic interests and policies.

Digital dependencies are integral to this objective. Huawei, 5G and fibre-optic networks are some of the ways that China is rewiring the region to its long-term benefit.

In the Chinese version of hegemony, so long as its industry and services enjoy supremacy in the Indo-Pacific and thus ensure the prosperity and wellbeing of the Chinese people, China is content to provide the public goods and financing for the region’s benefit as a sugar-coated pill.

The other facet of China’s potential hegemony is the idea that it is the region’s responsibility to accept and respect what China calls its ‘core’ concerns and interests. These are flexible and change according to the situation, but are always non-negotiable. What is ‘core’ will always be defined by China. The definition has expanded beyond issues of sovereignty and territorial integrity to cover economic, social and cultural issues, and even the persona of the Chinese leader. Those who don’t fall in line are apt to be taught a ‘lesson’.

India believes that the interests of the region are better served through a balance of forces rather than the preponderance of any single force—whether it is the Americans or the Chinese. This is one of the pillars of India’s Indo-Pacific vision.

Giving any country in this region a veto in the matter will be only at the peril of the security of the whole region. It should also be a matter of concern for others when China chooses to confuse the Indo-Pacific vision with plurilateral mechanisms like the Quad. The Quad is a platform for a group of countries that share common interests in the region they are located in. The Indo-Pacific is as much home to India, Australia and Japan as it is to China.

Many in the region look upon the US as a resident power, whose benign presence has been helpful to the region’s stability and growth. China itself has benefited from the American presence, not least in securing the capital and technology that has helped in its national rejuvenation.

Hence, labelling the Quad as a security hazard and threat to peace and development seems to be contradictory and self-serving. Contradictory, because China is the initiator of similar plurilateral mechanisms, including some in India’s neighbourhood. Self-serving because China doesn’t wish to permit any other platform that offers alternatives to the region.

The claim by China that the Quad is a historical regression and a danger to peace and security rings hollow, especially when it seeks to press centuries-old territorial claims on sea and land through the use of force.

If China is committed, as it claims, to uphold the principle of peace and stability and is ready to practice its diplomatic philosophy of affinity, sincerity and inclusiveness, it should desist from tilting at windmills and demonstrate this diplomatic philosophy in deeds.

China could begin by winding down the aggression it has displayed against its neighbours by unilaterally altering the status quo, and join the open discussion on the future of the Indo-Pacific.

India is willing to discuss Asian security with all parties in accordance with the principles of democratic and transparent engagement, and on the basis of respect for globally agreed norms of behaviour.

As if the raging Covid-19 pandemic, a spluttering economy, record-high unemployment and massive farmers’ protests besieging the country’s capital weren’t enough, India’s ruling Hindu-chauvinist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has now incited a new crisis: a culture war.

In late November, India’s largest state, BJP-ruled Uttar Pradesh, introduced a new law to combat the largely imaginary crime of ‘love jihad’—a conspiracy theory claiming that Muslim men seduce Hindu women as a ploy to oblige them to convert to Islam through marriage. The Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Ordinance stipulates that a marriage will be declared ‘null and void’ if a woman converts to Islam solely for marriage. Women wishing to change their religion after getting married need to apply to the district magistrate for permission, a breathtaking assault on individual liberty that combines misogyny, patriarchy and religious bigotry.

The measure is the brainchild of Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, a saffron-robed monk whose inflammatory rhetoric has made him one of the BJP’s best-known and most polarising figures. And it takes a sledgehammer to the freedom of worship enjoyed by Indian citizens under the country’s constitution. By the first week of December, state police had arrested and filed charges against seven people. Conviction carries a maximum sentence of 10 years’ imprisonment.

Much of India has long celebrated the intermingling of Hindu and Muslim cultural practices. But the Ganga-Jamni Tehzeeb, or ‘composite culture’, emerging from the interaction of the two faiths’ practitioners is now under assault from officially fomented bigotry. The BJP derives its political strength from campaigning aggressively as the vehicle of an assertive Hindu community, and regards stoking anti-Muslim sentiment as a vote-winner.

The BJP had previously campaigned successfully to build a Hindu temple on the site of a demolished mosque in Ayodhya, criminalise the Muslim divorce practice known as triple talaq, dismantle the special protections afforded to the Muslim-majority state of Jammu and Kashmir, and enact a law that excludes Muslims from the fast-track Indian citizenship available to refugees of other faiths. All of these steps have reinforced the party’s ‘tough on Muslims’ image, and Uttar Pradesh’s new anti-conversion law fits that pattern.

In recent weeks, other BJP-run states in India’s Hindi-speaking heartland have whipped up hysteria over ‘love jihad’, reflecting the party’s deeply entrenched Islamophobia. State governments in Madhya Pradesh and Haryana have announced plans to enact laws similar to that of Uttar Pradesh.

A BJP ‘youth leader’ in Madhya Pradesh has gone further, persuading the police to file a case against two Netflix executives for allegedly offending Hindu religious sensibilities with a scene in the series A Suitable Boy in which a Hindu actress and a Muslim actor kissed briefly in front of a temple. The leader, Gaurav Tiwari, demanded an apology from Netflix and the removal of ‘objectionable scenes’ that he alleged were also ‘encouraging love jihad’. Instead of dismissing the case as preposterous, the state’s home minister, Narottam Mishra, ordered an investigation.

Even reports that police in Uttar Pradesh have already dropped, for lack of evidence, eight of the 14 ‘love jihad’ cases they had opened are highly unlikely to dampen the BJP’s sectarian ardour. A few months ago, the jewellery brand Tanishq, which markets itself as the choice of ‘modern’ young consumers, was pressured, including by threats of violence, to withdraw a television commercial that portrayed a happy interfaith marriage between a Hindu woman and a Muslim man.

Although Islam remains its favoured target, the BJP’s Hindu chauvinists have also taken umbrage at the cultural practices of India’s Christian minority. A group of zealots called the Bajrang Dal, one of the BJP-aligned Hindutva (‘Hinduness’) movement’s many affiliated organisations, recently threatened violence against Hindus who visited churches during Christmas. Whereas Hinduism teaches reverence for other faiths, those who claim to be its doughty warriors admit no such ecumenism.

Valentine’s Day is another object of Hindutva warriors’ fury. Arguing that the occasion is un-Indian because it celebrates romantic love, they have attacked couples holding hands on 14 February, trashed stores selling Valentine’s Day greeting cards, and shouted slogans outside cafes while couples canoodled inside.

Ironically, the Hindutva brigade has no real understanding of Hindu tradition—their idea of Indian values is not only primitive and narrow-minded, but also profoundly ahistorical. India’s culture has always been capacious, expanding to include new and varied influences, from the Greek and Muslim invasions to the British.

The central battle in Indian civilisation today is between those who acknowledge that, as a result of India’s historical experience, our culture is as diverse as it is vast, and those who have presumptuously taken it upon themselves to define, in ever narrower terms, what and who is ‘truly’ Indian.

Modern Hinduism has always prided itself on its tolerance of differences. In fact, the modern era’s most famous Hindu sage, Swami Vivekananda, persuasively taught that the hallmark of Hindu civilization was not just tolerance but acceptance. With their narrow-minded bigotry, today’s Hindu chauvinists are fundamentally betraying their faith, as well as assaulting the constitution.

The issue is not trivial. If intolerant bullies, now enjoying the blessing of elected BJP governments, are allowed to get away with their acts of intolerance and ‘lawful’ intimidation, India will suffer violence to an ethos profoundly vital to its survival as a civilisation, and as a liberal democracy.

Pluralist and democratic India must, by definition, tolerate plural expressions of its many identities. If we permit the self-appointed arbiters of Hindu culture to impose their hypocrisy and double standards on the rest of us, they will define down Indianness until it ceases to be Indian. The BJP-led culture war must be fought in the courts, but it will be won only in the hearts of all Indians.

China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, recently declared that aggression and expansionism have never been in the Chinese nation’s ‘genes’. It is almost astonishing that he managed to say it with a straight face.

Aggression and expansionism obviously are not genetic traits, but they have defined President Xi Jinping’s tenure. Xi, who in some ways has taken up the expansionist mantle of Mao Zedong, is attempting to implement a modern version of the tributary system that Chinese emperors used to establish authority over vassal states: submit to the emperor, and reap the benefits of peace and trade with the empire.

For Xi, the Covid-19 pandemic—which has preoccupied the world’s governments for months—seemed like an ideal opportunity to make quick progress on his agenda. So, in April and May, he directed the People’s Liberation Army to launch furtive incursions into the icy borderlands of India’s Ladakh region, where it proceeded to establish heavily fortified encampments.

It wasn’t nearly as clever a plan as Xi probably thought. Far from entrenching China’s regional pre-eminence, it has intensified the pushback by Indo-Pacific powers, which have deepened their security cooperation. This includes China’s most powerful competitor, the United States, thereby escalating a bilateral strategic confrontation that has technological, economic, diplomatic and military dimensions. The spectre of international isolation and supply disruptions now looms over China, spurring Xi to announce plans to hoard mammoth quantities of mineral resources and agricultural products.

But Xi’s real miscalculation on the Himalayan border was vis-à-vis India, which has now abandoned its appeasement policy towards China. Not surprisingly, China remains committed to the PLA’s incursions, which it continues to portray as defensive: late last month, Xi told senior officials to ‘solidify border defences and ensure frontier security’ in the Himalayan region.

India, however, is ready to fight. In June, the PLA ambushed and killed Indian soldiers patrolling Ladakh’s Galwan Valley in a hand-to-hand confrontation that led to the deaths of numerous Chinese troops—the first PLA troops killed in action outside United Nations peacekeeping operations in more than four decades. Afterwards, Xi was so embarrassed by this outcome that, whereas India honoured its 20 fallen as martyrs, China refused to admit its precise death toll.

The truth is that, without the element of surprise, China is not equipped to dominate India in a military confrontation. And India is making sure that it will not be caught off guard again. It has now matched Chinese military deployments along the Himalayan frontier and activated its entire logistics network to transport the supplies needed to sustain the troops and equipment through the coming harsh winter.

In another blow to China, Indian special forces recently occupied strategic mountain positions overlooking key Chinese deployments on the southern side of Pangong Lake. Unlike the PLA, which prefers to encroach on undefended border areas, Indian forces carried out their operation right under China’s nose, in the midst of a major PLA build-up.

If that were not humiliating enough for China, India eagerly noted that the Special Frontier Force (SFF) that spearheaded the operation comprises Tibetan refugees. The Tibetan soldier who was killed by a landmine in the operation was honoured with a well-attended military funeral.

India’s message was clear: China’s claims to Tibet, which separated India and China until Mao’s regime annexed it in 1951, are not nearly as strong as it pretends they are. Tibetans view China as a brutally repressive occupying power, and those eager to fight the occupiers flocked to the SFF, established after Mao’s 1962 war with India.

Here’s the rub: China’s claims to India’s vast Himalayan borderlands are based on their alleged historical links to Tibet. If China is merely occupying Tibet, how can it claim sovereignty over those borderlands?

In any case, Xi’s latest effort to gain control of territories that aren’t China’s to take has proved far more difficult to complete than it was to launch. As China’s actions in the South China Sea demonstrate, Xi prefers asymmetrical or hybrid warfare, which combines conventional and irregular tactics with psychological and media manipulation, disinformation, lawfare and coercive diplomacy.

But while Xi managed to change the South China Sea’s geopolitical map without firing a shot, it seems clear that this will not work on China’s Himalayan border. Instead, Xi’s approach has placed the Sino-Indian relationship—crucial to regional stability—on a knife edge. Xi wants neither to back down nor to wage an open war, which is unlikely to yield the decisive victory he needs to restore his reputation after the border debacle.

China might have the world’s largest active-duty military force, but India’s is also massive. More important, India’s battle-hardened forces have experience in low-intensity conflicts at high altitudes; the PLA, by contrast, has had no combat experience since its disastrous 1979 invasion of Vietnam. Given this, a Sino-Indian war in the Himalayas would probably end in a stalemate, with both sides suffering heavy losses.

Xi seems to be hoping that he can simply wear India down. At a time when the Indian economy has registered its worst-ever contraction due to the still-escalating Covid-19 crisis, Xi has forced India to divert an increasing share of resources to national defence. Meanwhile, ceasefire violations by Pakistan, China’s close ally, have increased to a record high, raising the spectre of a two-front war for India. As some Chinese military analysts have suggested, Xi could use America’s preoccupation with its coming presidential election to carry out a quick, localised strike against India without seeking to start a war.

But it seems less likely that India will wilt under Chinese pressure than that Xi will leave behind a legacy of costly blunders. With his Himalayan misadventure, he has provoked a powerful adversary and boxed himself into a corner.

In the wake of the military face-off at Ladakh on the India–China Line of Actual Control (LAC) that led to the death of 20 Indian soldiers on 15 June, there’s been much talk in India about hitching India’s wagon to the US. Many commentators have argued that New Delhi should cooperate more vigorously and openly with Washington in the latter’s strategy to contain the growth of Beijing’s power and influence in the Indo-Pacific region.

This sentiment builds on India–US security cooperation both bilaterally and as part of the Quad, whose other members are Australia and Japan. All four share complementary interests vis-à-vis China, especially checkmating its growing intrusion in the South China Sea and restraining its reach through the Belt and Road Initiative. Japan and India have long-standing territorial disputes with China that they attribute to Beijing’s expansionist policy.

Advocates of closer India–US strategic cooperation against China base their arguments largely on recent statements by US President Donald Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo lambasting China’s aggressive policy, especially with regard to its moves in Ladakh. Pompeo accused China of taking ‘incredibly aggressive actions’ on the LAC and went on to say that ‘Beijing has a pattern of instigating territorial disputes [with its neighbours]. The world shouldn’t allow this bullying.’ Trump also declared that China’s aggressive stance along the India–China border fitted with a larger pattern of Chinese aggression in other parts of the world. ‘These actions only confirm the true nature of the Chinese Communist Party.’

While it is true that India–US relations have been on a remarkably upward swing in the last two decades in the economic as well as strategic (including nuclear) arenas, too much euphoria on this score could have negative fallout for India as well. The downsides include New Delhi becoming highly susceptible to Washington’s inducements to participate in the looming global confrontation with China that is widely predicted by strategic analysts, especially in the US.

India must remain wary of getting sucked into the new ‘cold war’ pitting the US against China. If New Delhi allows its territorial disputes with Beijing to become part of this global confrontation, it could lose any residual strategic autonomy it possesses and surrender its foreign policy to the whims and fancies of Washington. That mindset could easily lead to military overstretch on the assumption that the US would bail India out if matters escalated further on the LAC.

Such an assumption has the potential to cause an Indian military debacle in the Himalayas, where the Chinese hold the high ground and have over decades built accessible roads to the LAC for future military operations. While Indian road building has accelerated in the past few years, India still can’t match China’s preparedness on that score. And while India’s military preparedness today is far greater than it was in 1962, New Delhi can’t risk a major armed confrontation with China on the Himalayan front as it could have unforeseen consequences.

Disengagement and de-escalation on the India–China border would be bitter pills to swallow in the wake of Chinese intrusions but that would be far more prudent for India than taking a hard line based on an assumption about US assistance. Given that the US is already overstretched globally and the Trump administration is committed to military retrenchment from Germany to Afghanistan, any notion of American military support on the Himalayan front is a pipe dream. Public opinion in the US and the administration’s own predispositions would not permit it. And without a NATO Article 5–like commitment to come to India’s aid militarily if required, a tight American embrace won’t serve much purpose as far as New Delhi’s confrontation with China is concerned.

It would also affect India’s relations with Russia, which continues to be the principal supplier of sophisticated weaponry and the major source of spare parts for equipment in use by all branches of the Indian armed forces. While US threats to sanction India for buying Russian S-400 anti-missile systems have receded into the background for the moment, increased and overt dependence on the US to counter China would encourage Washington to tighten the screws on India again as part of its attempt to thwart the sale of sophisticated Russian weapons internationally.

Finally, India is heavily dependent on trade with China in key areas. It is estimated that in 2018–19, 92% of Indian computers, 82% of TVs, 80% of optical fibres and 85% of motorcycle components were imported from China. Even with the best of intentions, it would take India years to wean itself away from China in these and other important sectors. In the interim, India can’t afford to be seen as too closely allied with the US in the latter’s global rivalry with China because that could seriously disrupt the supply chain in these sectors. In addition, although India’s pharmaceutical industry is the third largest in the world in terms of volume, it imports two-thirds of bulk drugs or drug intermediates from China to keep the industry in operation.

India will have to tread very cautiously in aligning itself with the US to contain China. New Delhi must not rush into Washington’s embrace without carefully weighing the pros and cons of such a policy.

A slump in Australia’s trade with India undercuts the government’s hopes that the country might become a democratic counterweight to our economic dependence on authoritarian China.

While the headline coverage of last week’s official trade report seized on China’s share of Australia’s exports rising to an astonishing 46%, the fall in sales to India was overlooked. India’s share of Australia’s exports dropped below 2% in June, the lowest level since 2003.

It’s two years since the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade released an impressive strategy for building Australia’s economic relationship with India. The strategy review, led by former DFAT secretary Peter Varghese, set ambitious targets, including that Australia should lift its annual merchandise exports to India from the 2017 level of $15 billion to $45 billion by 2035, arguing that India should become Australia’s third largest export market.

At the time, this seemed plausible. The Indian market had been growing rapidly and it had already overtaken the United States to become Australia’s fourth most important market behind China, Japan and South Korea.

The review spelled out the geopolitical argument for building the economic relationship. ‘If we can count India in our top three export destinations and if we can tap more two-way investment between our countries, Australia’s exposure to global risk is reduced.

‘As partners in the Indo-Pacific, we are each grappling with the implications of the fading US strategic predominance and the sharpening ambition of China to become the predominant power in the region.’

But the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics report shows that in the year to June, India’s ranking among our export markets had slipped to seventh, surpassed by the US, the UK and Taiwan while China, Japan and South Korea forged further ahead. Merchandise exports to India of $11 billion over the last year were 26% below the 2017 level when the Varghese strategy was penned.

While the pandemic has depressed many export markets, the main reason for the slump in sales to India is its government’s nationalist ‘self-reliant India’ economic strategy which includes a target of eliminating coal imports by 2023–24. Coal accounts for around 70% of Australia’s exports to India.

The trade picture is no more encouraging on the import side, where India’s share of Australia’s purchases is down to 1.6%, having peaked at just 1.8% two years ago.

As well as setting a target for exports, the Varghese review also spelled out goals for investment, urging that India should become the third largest destination for Australian investment abroad in the Asian region by 2035.

Here, too, the data has been disappointing. Australian companies invested a paltry $114 million in India last year, while it accounts for a bare 0.2% of total Australian direct investment abroad. Within Asia, India ranks behind Singapore, China, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Indonesia and Vietnam as a destination for Australian direct investment.

Portfolio investment in Indian share and bond markets is higher, but still a microscopic proportion of the total, and it is really direct investment by businesses that matters for economic relationships. The stock of Indian direct investment in Australia is no higher now than it was in 2012.

Last week’s ABS trade report didn’t cover individual country markets for services, and India has been an important market for our higher education and tourism sectors. The latest figures for the export of services, which are a year out of date, show India ranking third behind China and the United States with exports of $6.6 billion.

When the pandemic subsides sufficiently for global travel to resume, India will be important for the recovery of Australia’s university sector, particularly if China delivers on its threat to cut back enrolments.

However, the ambition of building mutual economic bonds to underpin a geopolitical realignment with India is not realistic amid rising economic nationalism.

At the joint media conference with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi following their video meeting in June, Prime Minister Scott Morrison commented, ‘The trade and investment flows between our countries are not where [we] would both like them to be, but they are growing and they can grow a lot faster.’

As the latest trade reports show, they are contracting, not growing as the prime minister claimed, and it’s difficult to identify what might trigger a turnaround.

India’s economy was faltering ahead of the pandemic. Estimates of purchasing power by the International Monetary Fund show the economy rose by only 2.9% last year, which was only marginally better than during the depths of the global financial crisis and well below the 6% to 8% growth rates it had been accustomed to.

Modi argues that his economic strategy of self-reliance is not about isolating India from the world but is intended to strengthen the resilience of the domestic economy. He says his economic policy is consistent with greater foreign investment and India is pitching to global businesses to relocate their supply chains from China.

However, the self-reliance strategy, developed as a response to the slowdown, will be seen by Indian businesses as a licence to seek favoured treatment and protection. In the case of coal, the ambition is to build the state-owned Coal India as the dominant supplier to the exclusion of imports.

Morrison and Modi announced that they would restart negotiations on a bilateral free trade agreement which were abandoned in 2015. But the liberalisation of agricultural markets, which is always at the top of Australian negotiators’ priorities, is unlikely to make headway in India where the farm sector is highly inefficient but a vast source of employment. Australian tariffs are already so low that it has little to offer India in return for any concessions.

India has long been the most reticent participant in world trade liberalisation, and earlier this year withdrew at the eleventh hour from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership—a trade deal that would have drawn India into the Asian economic community.

The period ahead is likely to be marked across the world by poor business investment and slow growth of trade, with many countries acting in the same spirit as India: doing what they can to support domestic business and employment by adding protection against global competition. In this environment, there’s little likelihood of Australian exporters cracking any new markets of sufficient size to diversify our export profile away from China.

The defence outlook of major countries is fast changing amid the Covid-19 crisis and China’s increasingly coercive military posturing in the Indo-Pacific. Japan’s changing perspective on a first-strike capability, Australia’s 2020 defence strategic update, and India’s crafting of a comprehensive strategic partnership with Australia while purchasing the S-400 Triumf anti-missile system from Russia during the Galwan border clash with China are key indicators of how the Indo-Pacific powers are continuously changing their defence outlook. What scope do these developments create for the Australia–India defence partnership and where does India fit in Australia’s new defence strategy?

Australia’s strategic update and accompanying force structure plan revisit the defence outlook and reassess the challenges Australia could face in its region in the near term and long term. The update’s focus on the Indo-Pacific is a response to China’s behaviour in the region—from the South and East China Seas to the Pacific Ocean and the Taiwan front. With Canberra’s changing posture, India could emerge as a stronger defence partner than before.

The aim to advance ‘military interoperability through defence exercises’ under India’s new mutual logistics support agreement with Australia is a step in that direction. This arrangement gains strength from the two countries’ ongoing military modernisation, increasing the scope for defence and strategic cooperation. India is one of the leading importers of military equipment, but that hasn’t restricted it from planning to become self-reliant in arms and weapons manufacturing.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ (‘Self-reliant India’) strategy and ‘Make in India’ initiatives aim to make India self-sufficient in a number of sectors, including national security and defence. Those programs could see Australia emerge as a stronger partner in India’s arms procurement and defence modernisation process. The Indian defence procurement policy of 2016 encouraged joint development with original international equipment managers; the policy’s 2020 iteration follows similar lines while advocating for ‘Make in India’.

Closer collaborative ventures with Australian defence firms could boost India–Australia defence cooperation, especially in aerospace manufacturing, disaster relief, maritime security, shipbuilding, military infrastructure building and disruptive technology. Australia, too, is a net importer of defence equipment and plans to invest more than $200 billion over the next 10 years in building defence capability, which it hopes will support export opportunities for indigenous cutting-edge technologies and equipment.

India should also tap into Australia’s competitive defence technology and cybersecurity training sectors. The cooperation arrangements signed as part of the Australia–India comprehensive partnership include one on defence science and technology and another on cyber and cyber-enabled critical technology. In its 2020 strategic update, Australia has accorded immense importance to defence technology and cybersecurity due to the ever-expanding ‘threshold of traditional armed conflict in what experts call the grey zone’. The Australian government recently announced a $1.35 billion investment in enhancing cybersecurity capabilities.

While Australia’s defence export strategy of 2018 did not identify India as a close ally for export of its ‘sensitive technologies’, including India now as a major partner must become a necessity. Canberra’s strategic update should encourage Australia and India to cooperate in strategic thinking, meet grey-zone challenges, enhance their conventional capabilities and engage in stronger military-centric regional cooperation.

Australia and India had each long managed their relationship with China under an effective appeasement policy, but those strategies are undergoing serious revision.

Both countries have expressed concerns over China’s aggressive posturing in the South China Sea. An estimated two-thirds of Australian exports and more than half of Indian trade pass through the South China Sea, making it vital to their commercial interests. India and Australia share a vision of a ‘free, open, inclusive and rules based Indo-Pacific region’ in which freedom of navigation and overflight, and peaceful and cooperative use of the seas, are upheld.

Cooperation on the South China Sea could be more thorough, however. Australia’s inclusion in the Malabar naval exercise with India, Japan and the US is vital in this regard. Australia’s participation in the exercise is emerging as an almost foregone conclusion, though no formal announcement has yet been made.

The partnership between Australia and India is no longer one-dimensional, and to be truly comprehensive it needs to have many layers. The Indian market might appear to be complex, but it is also ‘very fast moving’, as Australia’s trade minister Simon Birmingham said recently. India is the fifth-largest export market for Australia and is ranked as its eighth-largest trading partner, yet two-way trade is still unimpressive at $30.3 billion in 2018–19.

Stronger defence cooperation could emerge out of stronger economic ties. The time has come for Australia to factor India much more seriously into its defence planning and to foster a stronger, market-oriented defence partnership.