The thin veneer of India’s constitutional secularism

After India’s recent defeat by Pakistan at the T20 World Cup cricket tournament, Indian bowler Mohammed Shami confronted vicious trolling on social media. It was the latest display of the Islamophobic bigotry that has consumed Indian society under the rule of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Shami had performed poorly in the match. But so had 10 other Indian players in the rout by Pakistan. Shami was singled out because he is Muslim. His failure was viewed not merely as a sporting issue, but as a failure to do his best against an opposing team composed of his co-religionists.

Unpleasant as it was, the Shami episode pales in comparison to other recent incidents of Islamophobia in India. In Darrang district, in the northeastern state of Assam, the state’s BJP government launched an eviction drive against Muslims whom it decided were ‘illegal settlers’ on public land. During a protest against the evictions, police shot and beat a villager, and a photographer officially documenting the demolition drive brutally stomped him, in full view of cameras, even after his body appeared lifeless.

Video footage of the murderous assault went viral on social media, prompting much hand-wringing among those sections of the Indian public not yet inured to stories of violent hate crimes against its Muslim minority, which have proliferated under BJP rule. In recent years, a spate of inflammatory anti-Muslim rallies have sometimes erupted in violence. In February 2020, riots consumed parts of the capital, New Delhi, leaving more than 53 dead. Most of the victims were Muslim.

There has also been a dramatic increase in lynchings of Muslims, especially for the ‘offence’ of transporting or consuming beef (the cow is considered holy in Hinduism). Most states have enacted laws prohibiting the slaughter of cows, and both police and self-appointed mobs are enforcing them with greater zeal than judgement. Cow ‘vigilantes’ have been known to beat Muslims, forcing them to chant Hindu religious slogans. Such hate crimes are committed with impunity.

Meanwhile, police have charged Muslim students under draconian terrorism and sedition laws for the frivolous ‘crime’ of cheering for Pakistani cricketers. Four Muslims were arrested in the city of Indore for attending a popular annual college dance celebration that was abruptly classified as restricted to ‘Hindus only’. A Muslim journalist, Siddique Kappan, has been jailed for more than a year on charges of sedition, terrorism and incitement, when all he did was his job.

As disturbing as these trends are, they should not be surprising, given that senior political figures express their bigotry openly. Modi once declared that anti-government protesters could be identified by their clothes—that is, traditional Muslim attire. And prior to the 2019 general election, BJP president Amit Shah called Bangladeshi Muslim immigrants ‘termites’ and pledged that a BJP government would ‘pick up infiltrators one by one and throw them into the Bay of Bengal’. Islamophobic sentiment is stoked further via social media, often in BJP-curated WhatsApp groups, where the sins—both real and imagined—of past Muslim invaders and rulers are blamed on the entire community.

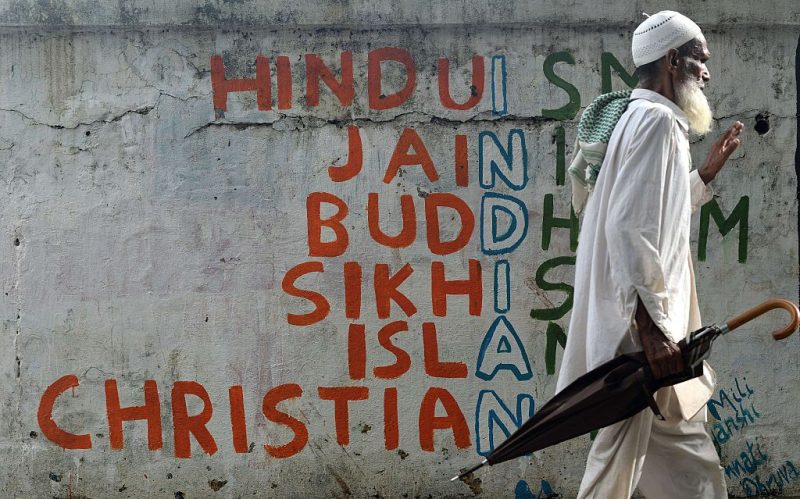

Whereas previous governments sought to temper communal passions, promote harmony and provide official support (including tax incentives) for efforts to promote India’s pluralism and diversity, the BJP unapologetically embraces an intolerant majoritarian ‘Hindutva’ ideology. Those close to the ruling establishment routinely excoriate the Muslim minority—and previous governments’ alleged appeasement of it—as a threat to India’s Hindu identity.

Under BJP rule, campaigns have been launched against interfaith romance (with Muslim men being accused of waging ‘love jihad’ to entrap Hindu women), religious conversion (despite it being permitted by India’s constitution) and Muslim practices of marriage, divorce and alimony (which are viewed as incompatible with women’s rights). A popular clothing firm was browbeaten into withdrawing an advertising campaign deemed by zealots to be inserting Muslim elements into the Hindu festival of Diwali. A Muslim religious gathering was deemed a Covid-19 super-spreader event, even as the far larger Hindu Kumbh Mela festival was allowed—even encouraged—to proceed.

The BJP government also enacted a law offering fast-track citizenship to refugees from neighbouring Muslim-majority countries—provided they were not Muslim. And family-planning campaigns have been portrayed as efforts to preserve India’s ‘demographic balance’—India is 80% Hindu—in the face of higher Muslim fertility.

What dismays liberals like me is how thin the veneer of India’s constitutional secularism has turned out to be. In just seven years of BJP rule, the cultural pluralism and Hindu–Muslim amity that India has touted for decades have been annihilated.

There was a time when government officials would point proudly to Muslims in prominent positions as evidence of India’s ability to overcome the bitter legacy of partition with Pakistan. Today, Muslims are dramatically underrepresented in the police forces and elite central administrative services, and they are overrepresented in the prisons. Sentiments that would have been deemed impolite to express a generation ago are declaimed from political platforms. The police often enable, rather than stop, the torment of Muslims.

Islamophobia now seems to have colonised a significant segment of north Indian society, though the south has yet to succumb. India’s much-vaunted free press has been complicit—and even an active participant—in the erasure of its longstanding syncretic cultural traditions.

Under BJP rule, the segregation and disempowerment of Muslims—the division of Indian society into ‘us’ and ‘them’—is being gradually normalised, and Indians are becoming desensitised to the routine expression and practice of anti-Muslim bigotry. A Muslim who points this out will be told to ‘go to Pakistan’. Hindus like me are derided as ‘anti-national’.

I have been called that myself. In 2015, speaking in parliament, I repeated a friend’s observation: in BJP-ruled India, it is safer to be a cow than a Muslim. Sadly, that rings even truer today.