Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

There’s a sense of foreboding in New Delhi as Xi Jinping prepares to secure a third five-year term as China’s president. It’s expected that Xi’s appointment will be confirmed by the 20th congress of the Chinese Communist Party, which begins in Beijing on 16 October.

Under Xi, China has, with relentless pugnacity, challenged India’s sovereignty by encroaching on its territorial waters and redrawing the Line of Actual Control, the 3,488-kilometre Himalayan frontier that divides the nuclear-armed neighbours.

Xi queered the pitch further by rebuffing India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who had been looking forward to a separate meeting with him at last week’s Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit in Uzbekistan. Xi pointedly did not acknowledge Modi even when the Indian leader walked up to him at the photoshoot of the organisation’s leadership.

Modi has hitherto been unable to raise with Xi the issue of Chinese troops on Indian territory since their violent cross-border clash with Indian soldiers on 5 May 2020. Chinese troops also slew 20 Indian soldiers in the area on 15 June 2020, the first deadly skirmish since 1967, when a border confrontation led to the deaths of 80 Indian and 400 Chinese soldiers. It is widely believed that a direct discussion would have helped defuse the tensions.

This has raised concern about an apparent communication gap between the two leaders. Modi has previously claimed a close rapport with Xi, built up over his nine visits to China, five as prime minister and four previously as chief minister of Gujarat state. He also hosted the Chinese president in India three times between 2014 and 2019.

Moreover, even as corps commander-level talks on disengagement and de-escalation continue between the two countries, Modi has avoided identifying China as the aggressor, asserting instead, ‘No intruder is present inside India’s borders, nor is any post under anyone’s custody.’

India has demonstrably been pushed onto the back foot as more than 50,000 People’s Liberation Army troops continue to occupy 1,000 square kilometres of the eastern sector of India’s border union territory of Ladakh.

While an intransigent China has not heeded India’s call for reinstatement of all the captured territories, it consented to a localised disengagement by Indian and Chinese frontline troops being carried out last week from Patrolling Point 15 in Gogra-Hot Springs, as per the agreement reached at the 16th round of talks in July.

A similar breakthrough had been reached once before, at the 9th round of talks in January 2021, which led to disengagement at the south and north banks of the Pangong Tso lake.

While China yielded some ground, India appears bereft of any comprehensive strategy to deal with the situation. New Delhi’s anxiety about pursuing a negotiated conciliation has been prompted by the vast disparities between their forces. Military retaliation is not an option for India, as it strives to prevent the hostility spiralling into an all-out war it can ill-afford.

Though India has affirmed that only complete disengagement can lead to de-escalation of hostilities, it hailed the limited withdrawals as major concessions it extracted from Beijing. However, it has ceded territory to China by agreeing to the pullbacks from areas well within its borders and to the creation of ‘buffer zones’ inside its territory.

It also remains to be seen how long this disengagement will hold. PLA troops recrossed the LAC following the 2021 disengagement to reoccupy positions on the Kailash Range that they had vacated, and others moved in to points near the Pangong Tso and Galwan river.

A menacing China has opened additional fronts along India’s border states of Arunachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Sikkim. Beijing has all along claimed the 83,743square kilometre Arunachal as part of southern Tibet. In 2018 its state-run English-language daily Global Times asserted: ‘Although China recognised India’s annexation of [7,096 square kilometres] Sikkim in 2003, it can readjust its stance on the matter.’

The PLA has also brought in medium-lift helicopters, towed artillery, light tanks, infantry combat vehicles, rocket launchers and drones with thermal imaging, and created extensive support infrastructure with fortifications and encampments, all within striking distance of Indian deployments. It has also laid fibre-optic cables to secure lines of communication between forward troops and bases in the rear.

China’s push against India doesn’t appear merely tactical, but has a strategic intent with long-term objectives. These moves are not directed by exuberant commanders on the ground, but by the topmost leadership, the Central Military Commission, chaired by Xi.

Despite three previous border agreements, Beijing disputes most of its territorial demarcations with India. In 2017, it had a 73-day standoff with India at the India–China–Bhutan tri-junction of Doklam, the most critical in decades.

India has reason to fear a progressive deterioration in its security environment, with the CCP congress expected to cement Xi’s place as the country’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong. Xi made this possible when in 2018 he rescinded the two-term limit for the presidency. He has served as CCP general secretary and chair of the Central Military Commission since 2012 and has been president since 2013.

Recently in New Delhi, Indian foreign minister S. Jaishankar observed: ‘It is said that the prerequisite for an Asian Century is an India and China coming together.’

Conversely, he said, the inability of these nations to work together will undermine that goal.

During a parliamentary debate in April, I expressed my concerns about India’s relationship with Russia. My words were met with grim-faced silence. But the events of the last five months have only strengthened my case.

The debate was on the Ukraine war. While deploring India’s reluctance to call a Russian shovel a spade, I acknowledged that India has historically depended on the Kremlin for defence supplies and spare parts, and appreciated Russia’s long-standing support on vital issues like Kashmir and border tensions with China and Pakistan. But the Ukraine war and Western sanctions had weakened Russia considerably, I noted. The ban on semiconductor chips, for example, had significantly eroded its ability to produce advanced electronics and defence goods that form the basis of India’s dependence.

Worse still, I argued, the war had highlighted and reinforced Russia’s reliance on China as its principal global partner—a relationship that would intensify as Russia grew weaker. India could then scarcely depend on the Kremlin to counter Chinese aggression, exemplified by the People’s Liberation Army’s territorial encroachments and killing of 20 Indian soldiers in June 2020.

My Russian (and Russophile) friends pooh-poohed my fears privately, expressing confidence that Russia was doing far better than the Western media had led the world to believe. India’s purchases of discounted oil and fertiliser have increased significantly since the war began—though a 30% discount on oil prices that have gone up 70% because of the war can hardly be considered a bargain. More important, China and Russia do indeed seem to be deepening their ties, which augurs ill for India’s relationships with both countries.

Russia invaded Ukraine just a few weeks after Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping announced their ‘no limits’ partnership. And since the war began, both countries have repeatedly affirmed their geopolitical concordance.

Last month, Putin’s press secretary, Dmitry Peskov, denounced the United States for permitting House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi to visit Taiwan. ‘This is not a line aimed at supporting freedom and democracy’, he declared. ‘This is pure provocation. It’s necessary to call such steps what they really are.’

A week later, China returned the favour. In an interview with the Russian state news agency TASS, China’s ambassador to Russia, Zhang Hanhui, called the US ‘the initiator and main instigator of the Ukrainian crisis’. Echoing another favourite Kremlin line, Zhang also stated that America’s ‘ultimate goal’ is to ‘exhaust and crush Russia with a protracted war and the cudgel of sanctions’.

While this sort of reciprocity points to a growing awareness of shared geopolitical interests, it cannot obscure the fundamental imbalance in the bilateral relationship. Straining under the weight of Western sanctions, Russia depends heavily on China, not least as an export market and a source of vital supplies. Chinese imports from Russia have increased by more than 56% since the war began, and China is the only country that can provide Russians with consumer goods that once came from Europe and the US. According to Alexander Gabuev, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the Chinese renminbi could well become ‘the de facto reserve currency for Russia, even without being fully convertible’.

Xi, who will soon be confirmed as China’s paramount leader for an unprecedented third term, is well aware of this imbalance and is reaping massive rewards from it. In backing Russia diplomatically, he demonstrates his refusal to be cowed by the West. At the same time, he is benefiting from China’s increasing dominance over Russian markets and the renminbi’s enhanced status. And it doesn’t hurt that Chinese companies—which have been reeling from regulatory crackdowns since late 2020—can turn a tidy profit from their sales to Russia.

The Kremlin is in no position to complain about Chinese price-gouging, let alone alienate China by failing to support its stance on key issues like Taiwan. As Gabuev put it, ‘Russia is turning into a giant Eurasian Iran: fairly isolated, with a smaller and more technologically backward economy thanks to its hostilities to the West.’ With few friends, Russia knows that it has little choice but to stick with China—a stance that will likely be on display when Putin meets with Xi at this month’s Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit.

Against this backdrop, India must urgently review its geopolitical options. It must recognise that it has never needed Russia less. Its dependence on Russian military supplies—for which it pays top dollar—has fallen from 75% in 2006–10 to below 50% in 2016–20 to an estimated 45% today. This reflects India’s efforts to diversify its defence purchases, with the US, France and Israel becoming key suppliers. And US support means that India no longer needs Russia’s veto power to keep Kashmir off the agenda at the United Nations Security Council.

India must also recognise the need to cooperate with others to constrain China’s overweening ambitions. Given its gradual transformation into a satellite state of a rising Chinese imperium, Russia is an increasingly implausible partner in any such effort. The need for India to establish and shore up its own partnerships is magnified by the risk of a hostile China–Pakistan axis on its borders. Russia will be ambivalent, at best, about such an axis; at worst, it will be complicit. The Russia of the foreseeable future, severely weakened by its Ukrainian misadventure, is not a Russia on which India can rely.

The war in Ukraine has created new geopolitical fault lines, forcing countries to make difficult strategic choices. India must do the same.

South Asian social media is now a contested space. Multiple politically motivated actors deploy inauthentic accounts to shape the discourse on the region’s historical and modern geopolitical disputes.

One of the region’s longest running disputes is over Kashmir. India and Pakistan have fought two wars and multiple smaller armed conflicts over the region. Multiple attempts at peace negotiations haven’t yielded results. Today, Kashmir is claimed by both India and Pakistan, but each state controls parts of the region, and China also controls territory ceded by Pakistan but claimed by India as part of Kashmir.

Present-day Kashmir remains highly militarised and experiences extraordinary levels of state control. In 2019, the region went through a fresh round of tensions, starting from the death of 40 Indian soldiers in an attack linked to a Pakistan-based terrorist group, which led to a cross-border strike by India and skirmishes between the Indian and Pakistani air forces. In August 2019, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi delivered on his party’s manifesto by removing the region’s constitutional privileges, which gave Kashmir a high degree of autonomy and divided the state into two federally controlled territories. That was followed by an internet and media blackout, an increased Indian Army presence and a strongly enforced ban on public gatherings.

These historical conflicts and the resulting domestic political motivations have now polluted the region’s social media and political discourse with coordinated activity aimed at hijacking or disrupting genuine debate, discussion and movement.

Since tensions flared between India and Pakistan in 2019, multiple suspicious and coordinated accounts have sought to shape narratives relating to Kashmir on social media platforms. Examples include two hashtags, #KashmirWithModi and #KashmirWelcomesChange, which were posted by legitimate Twitter users before being used by suspicious accounts to disseminate misleading content showing local Kashmiris reacting favourable to the Indian government. Around the same time, Twitter accounts—presumed to have originated from Pakistan—also amplified two competing hashtags, #IndiaUsingClusterBombs and #KashmirUnderThreat.

Meta has also identified coordinated inauthentic behaviour believed to have originated in India and Pakistan in April 2019, and has removed four networks from its Facebook platform.

Earlier this month, ASPI received a dataset from Twitter of 1,198 accounts that amplified content favourable to the Indian government and were suspended for breaching Twitter’s platform manipulation and spam policies. Activities that might constitute breaches include artificially amplifying or suppressing information, mass-registering accounts, and conducting coordinated operations to disrupt conversations. These behavioural indicators were used by Twitter to delineate between legitimate users and coordinated, well-resourced and politically motivated actors.

In this dataset, accounts sought to influence public opinion about Kashmir, Pakistan and the Indian Army, and to promote a positive view of the Indian government after the removal of Kashmir’s constitutional privileges. According to Twitter, these accounts are presumed to have been located in India and, surprisingly, the United States. Twitter also disclosed a separate network of 568 accounts and 4,418,374 tweets, presumably originating in Pakistan. Analysis of that dataset was outside the scope of this investigation.

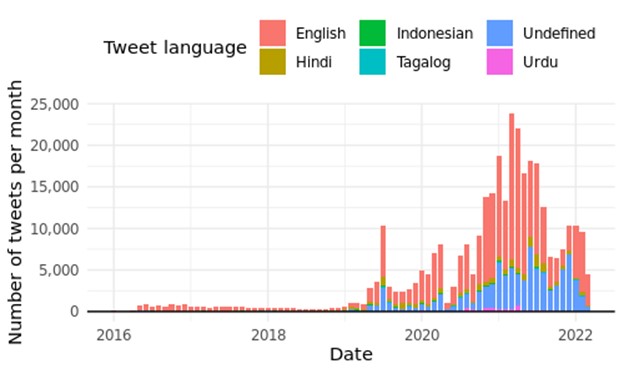

This latest India/US-originated multi-year dataset contained more than 360,000 tweets and 107,600 media files posted mostly between June 2019 and January 2022. Tweets were posted mainly in English and Hindi, indicating that the operations likely targeted both South Asian and international audiences. The frequency of posts reached a relative peak in June 2019, but the majority were posted during the end of 2020 and the first half of 2021.

Number of tweets posted per month by top six most frequently used tweet languages

Analysis of the most frequently used hashtags in this multi-year campaign showed that tweets primarily targeted online discourse relating to Kashmir. For example, the hashtags #GreenForKashmir and #RedForKashmir were used in 5,496 and 2,268 tweets respectively in June and July 2021. The #RedForKashmir hashtag is part of a social media movement that originated in the US aimed at protesting the Indian government’s removal of Kashmir’s special constitutional status. Our analysis showed attempts to hijack this hashtag with innocuous tweets or tweets portraying the Indian Army in a positive manner.

For example, the screenshot on the left below shows a legitimate and verified account using the #RedForKashmir hashtag to criticise the Indian government, while the screenshot on the right is a tweet posted by an account that uses common hashtags and text positively depicting the Indian Army found in the suspended campaign.

Many accounts currently active on Twitter are likely part of this network—but appeared to have evaded Twitter suspension—and continue to co-opt the #RedForKashmir hashtag and amplify the #GreenForKashmir hashtag.

For example, a tweet posted by zoya (below) uses the same tweet text and hashtags as users suspended in this dataset.

Beyond Kashmir-related content, the operators of this network sought to shape public perception about other territorial or political disputes in South Asia.

This included content about Balochistan, Pakistan’s largest province, which has faced separatist movements and accusations of human rights abuses by the local authorities. The hashtag #Balochistan was used 3,625 times (making it the 11th most frequently used hashtag) in the context of tweets calling for Balochistan independence and undermining the Pakistan Army in the region. The second most retweeted account was the official Twitter account of Sher Mohammad Bugti, the central spokesman of the Baloch Republican Party, a banned organisation in Pakistan that seeks Baloch independence.

In another example relating to modern geopolitical tensions, accounts in this network also sought to counter perceptions about China. The most shared link (4,357 times) was an Indian news agency article about China facing an economic slowdown. Funding issues with the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, a collection of major infrastructure projects in Pakistan that’s seen as the main plank of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, were mentioned in 1,316 tweets.

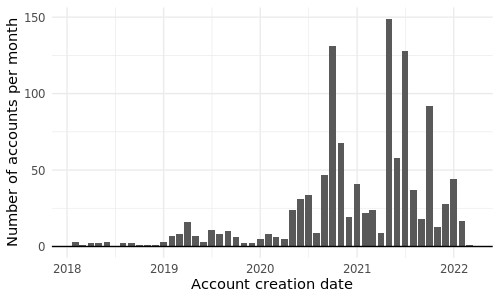

Overall, accounts in this network deployed the usual tactics to artificially amplify information favourable to their political goals and maintain a sustained presence on Twitter. Of all the posts in the dataset, 30.1% were retweets and mostly sought to artificially amplify tweets that were favourable to the Indian government. Accounts were created constantly throughout 2019 to 2022. The majority were created after 2020. Only 29 accounts (2.4%) were created before 2018, and they are likely commercial spam accounts that were later repurposed for political activity.

Number of accounts created per month between January 2018 and March 2022

This sustained multi-year campaign is one of many examples of how South Asian social media is now overcrowded with politically motivated actors seeking to interfere in or disrupt online discourse on the region’s most important disputes. Tweets in this campaign mostly received low engagement from legitimate users, but the volume and veracity of tweets suggests an escalating and persistent campaign.

Larger questions about the implications of restricting the rights of citizens to participate in democratic discourse and undermining the use of social media platforms as tools in human rights movements are left unanswered. As the region becomes more contested, covert and coordinated activities like this operation could undermine norms of behaviour that are conducive to open democracies.

India is no stranger to political controversies. At least half a dozen rage in its fractious public life at any time. But perhaps the most unseemly recent dispute has been the current one over the country’s Covid-19 mortality figures.

The pandemic hit India hard, particularly during the second wave in April–June 2021, when people were dying from Covid-19 in hospital waiting rooms and carparks, while others succumbed due to a lack of medical oxygen. Countless funeral pyres glowed in the darkness along the banks of the Ganges, even as some poor families, unable to afford a funeral, wrapped their loved ones in shrouds and sent them floating down the river.

But, despite widespread anecdotal evidence of a catastrophic pandemic death toll, official Indian figures told a different, although still alarming, story. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government estimated that, between the start of the pandemic in January 2020 and March 2022, just over half a million deaths were attributable to Covid-19. Many Indian journalists were sceptical, pointing out that the official figure was well below even the number of compensation payouts made by state governments to the families of Covid-19 victims. The respected British medical journal The Lancet published a study suggesting that India’s numbers were a gross undercount. But the government stood its ground.

It took an explosive report from the World Health Organization earlier this month to blow the lid off the government’s claims. Using the measure of ‘excess deaths’—based on pre-pandemic mortality rates in the same area—the WHO estimated the number of Covid-19 deaths in India at 4.7 million. That was nearly 10 times higher than the government was prepared to admit and accounted for almost a third of the estimated 15 million pandemic deaths globally.

The government, which had at first tried unsuccessfully to stall the adoption of the report, denounced it, citing concerns about the WHO’s methodology. But, given that lower Covid-19 mortality figures are an essential part of the government’s messaging, the denials were widely seen as an attempt to counter unfavourable publicity about its management of the pandemic.

India is an important member of the WHO, and its health minister chaired the body’s executive committee during the first year of the pandemic. It is safe to assume that, as a United Nations organisation, the WHO has no desire to score political points against the government of a leading member state. But the need to have an accurate Covid-19 mortality count so that the world can prepare better for the next pandemic obliged the organisation to ignore the sensitivities of national governments and issue its report. (Several other calculations and surveys had reached similar conclusions about the scale of Covid-19 mortality in India, with estimates putting the death toll at 3–5 million.)

Ironically, the WHO’s figures nonetheless confirm that India did not do all that badly relative to other countries in tackling the pandemic. Although India’s Covid-19 fatality rate of 1.2% of confirmed cases is the seventh highest globally, the country does not figure in the top 100 in terms of deaths per million population. It’s possible that many more people in India were infected than diagnosed, and that the true fatality rate is therefore lower, even if the absolute numbers are high as a result of India’s large population.

It would therefore have been better for the government to accept the WHO’s figures and frame them as relatively good news, rather than kicking up a controversy that has put it in an unflattering light internationally. By challenging a well-established methodology used by epidemiologists worldwide, the government has triggered much more discussion of the inadequacies of India’s civil registration system, its reporting of infections and deaths, and the credibility of its official statistics more generally.

India should have admitted that the draconian, Chinese-style lockdown the government imposed when the pandemic began in 2020 paralysed much administrative activity, including the reporting and registration of deaths (not just from Covid-19). Field surveys were not conducted and statistical sampling was based on inadequate data. While things improved in that regard in 2021, shifting patterns of lockdowns and the severity of the second wave also interfered with the maintenance of accurate records. The government could simply have asked the WHO to include a footnote in the report explaining that, for these reasons, the organisation’s estimates of Covid-19 deaths in India were based on a modelling exercise.

Instead, Indian officials made the preposterous claim that 99.9% of all Covid-19 deaths to date were registered in 2020, and that the increase in ‘excess deaths’ really reflects an improvement in registration. This is so palpably untrue as to cast doubt on the government’s overall trustworthiness.

A country whose statistics were once considered a model for the developing world has embarrassingly been portrayed as one whose official numbers are tailored to suit the government’s preferred narrative. Amid widespread international scepticism about the integrity of India’s official mortality data, the WHO has relegated India to a category of countries whose Covid-19 numbers must be estimated through statistical models instead.

Life and death cannot be a matter of opinion. Accurate mortality figures enable a country to understand the scale of a tragedy, honour the dead, compensate the living and better gauge what kind of measures will be required to prepare for future public-health crises.

Towards the end of March, an unusual sequence of diplomatic visitors passed through India’s capital. First came Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, Austrian Foreign Minister Alexander Schallenberg and US Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Victoria Nuland. They were followed by Greek Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias, Omani Foreign Minister Sayyid Badr Albusaidi and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

The parade continued. Next to arrive were Gabriele Visentin, the European Union’s special envoy for the Indo-Pacific; Marcelo Ebrard, Mexico’s foreign minister; Jens Plötner, foreign and security policy adviser to German Chancellor Olaf Scholz; and Geoffrey van Leeuwen, foreign affairs and defence adviser to Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte. Last and by no means least were US Deputy National Security Adviser Daleep Singh, UK Foreign Secretary Liz Truss and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. There was also an online Indo-Australian summit.

The Ukraine war has exposed India’s strategic vulnerabilities in a tough neighbourhood as arguably nothing else could, raising fundamental questions about the country’s global position and regional security. But, paradoxically—as the slew of recent high-profile visits confirms—the conflict has increased India’s strategic importance and, in the short term, widened its options.

Has Prime Minister Narendra Modi used this room for manoeuvre well? The West, even as it seeks to line up India on its side vis-à-vis Ukraine, has signalled its understanding of India’s dependence on Russia for vital defence equipment and long history of close diplomatic relations with the Kremlin.

China has been somewhat surprised to find itself on the same page as India regarding the war. Both countries abstained in a series of United Nations votes condemning the Russian invasion and have maintained their communication channels with the Kremlin despite Western sanctions. China has been asking for restoration of ‘normal’ bilateral relations with India, which have been in a deep freeze since violent border clashes in June 2020 killed 20 Indian soldiers. ‘The world will listen when China and India speak with one voice,’ Wang reportedly stated on his recent visit to Delhi.

Russia, no doubt eager to thank India for ‘understanding’ the Kremlin’s position, has offered the country economic incentives—notably, discounted oil and gas and affordable fertiliser—to dissuade it from changing its stance.

While India’s longstanding focus on ‘strategic autonomy’ has kept it out of formal alliances, its broad geopolitical orientation has been veering towards a special partnership with the United States, notably in the Indo-Pacific. India is a member of the US-led Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, an informal grouping also including Japan and Australia that is widely seen as a way to check China’s regional ambitions.

India has also significantly increased its defence purchases from the West in recent years, and, with the US, is seeking to modernise its manufacturing base for military equipment. This process is likely to be accelerated by India’s realisation that its dependence on Russian supplies imposes significant constraints, particularly in the event of a future border crisis with China.

Singh, the US deputy national security adviser, pointedly warned of ‘consequences’ should India breach the Western-led sanctions on Russia, and he urged India to recognise the diminishing value of its close relationship with the Kremlin. ‘The more Russia becomes China’s junior partner, the more leverage China gains over Russia, the less and less favourable that is for India’s strategic posture,’ he told an Indian TV channel. ‘Does anyone think that if China breaches the Line of Actual Control, that Russia would now come to India’s defence? I don’t.’

China has been pushing the BRICS grouping (of which it is a member, along with Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation as models of non-Western collaboration that can ensure a multipolar world order. But Chinese blandishments towards India are unlikely to succeed if China’s leaders aren’t willing to reverse their military gains from unprovoked Himalayan incursions in mid-2020. India will accept nothing less than a return to the status quo ante of April 2020 as the price for normalising bilateral relations. But whether it can leverage China’s overtures to achieve results on the ground remains to be seen.

Russia, meanwhile, is aware that India’s refusal to condemn its assault on Ukraine doesn’t imply support. India has at no stage endorsed the Russian military campaign, and its language has notably hardened as the war has dragged on. Indian statements now pointedly refer to the inviolability of borders, respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of states, and the inadmissibility of resorting to force to resolve political disputes, even while calling on ‘both sides’ to pursue diplomatic negotiations.

India has also been quick to provide humanitarian assistance to Ukraine, sending 90 tonnes of relief materials. As the destruction has become more intense, its aid is likely to continue. India will gladly purchase essential supplies of fuel and fertiliser from Russia at discounted rates in roubles. But its diplomatic stance, and decreasing reliance on Russian defence equipment, mean that it’s not completely in Russia’s camp.

Still, India’s calls for peace in Ukraine would have been more credible had it taken steps to bring about that outcome. Whereas countries like Turkey and Israel have been actively engaged in peace diplomacy, India has made no effort to play a mediating role, despite at one point sending four cabinet ministers to Europe to supervise the evacuation of Indian citizens from Ukraine. Even Lavrov suggested in Delhi that India could help ‘support’ a mediation process.

India could have used the diplomatic attention it has been getting over Ukraine to carve out a role worthy of its aspirations for a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. Sadly, its ambitions seem to have been too modest.

India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, observed in 1946, ‘India, constituted as she is, cannot play a secondary part in the world. She will either count for a great deal or not count at all.’ Ukraine is a test case, and the jury remains out. Will today’s India count at all?

On Monday, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison held the second India–Australia virtual summit. At the meeting, the two leaders reaffirmed their commitment to the India–Australia comprehensive strategic partnership and welcomed the considerable progress made in strengthening political, economic, security, technology, cyber and defence cooperation.

In the defence realm, the leaders agreed to pursue opportunities for further cooperation in areas including military-to-military relationships, maritime information sharing and domain awareness, and underscored the importance of reciprocal access arrangements.

While encouraging progress is being made, much more could be done to facilitate deeper operational defence cooperation.

India and Australia have tightened their strategic relationship over the past two decades, with their watershed 2009 joint declaration on security cooperation becoming a comprehensive strategic partnership in June 2020. The two countries now have regular 2+2 foreign and defence minister meetings and close cooperation between their militaries, and also meet in conjunction with Japan and the United States through the Quad.

The context of international relationships is being looked at in a new light after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Now entering its fifth week and with Russian forces making slow progress, a supposedly swift invasion has the possibility of becoming a prolonged urban war. A host of countries from Europe, along with the US, Japan, Australia and others, have imposed a suite of harsh economic sanctions on the Russian state and its oligarchs. Most of the international community has voted to condemn Russia’s actions through the United Nations Security Council, General Assembly and Human Rights Council.

A small group of countries continue to support Russia, some of which have chosen to abstain on the UN votes and declined to concede that Russia ‘invaded’ Ukraine. Among those countries is India, which has faced some backlash, particularly from Western commentators, for not criticising Russia’s actions.

Moscow has been a time-tested partner for New Delhi across many decades, with close military and strategic ties and an enduring economic and diplomatic relationship. As many Indian commentators and foreign policy experts have pointed out, India’s position on Russia should come as no surprise because of their shared history from soon after Indian independence and India’s heavy reliance on Russian military equipment.

Despite its increasingly close strategic ties with the US and some of its allies since the turn of the century, India has also long espoused a strategy of non-alignment, or what has come to be known as multi-alignment. To be sure, Western governments have been careful not to overly criticise New Delhi. US State Department spokesperson Ned Price said the US shares important interests and values with India and noted that ‘India has a relationship with Russia that is distinct from the relationship that we have with Russia. Of course, that is okay.’

Unsurprisingly, a hastily convened virtual Quad meeting following the Ukraine invasion didn’t elicit any change of approach from the Indian government. In fact, the meeting only served to distract from the Quad’s core focus on the Indo-Pacific.

One area in the relationship with Moscow that is now giving New Delhi some food for thought is its overreliance on Russian military equipment. The issue is two-fold, encompassing India’s dependence on Russian supply chains and the vulnerabilities of some Russian military equipment that are now being exposed by Ukrainian and Western countermeasures. Just as troubling are the roles Russian equipment and know-how play in India’s ‘Make in India’ military indigenisation process. These factors will become more pronounced the longer Russian forces get bogged down in a protracted and costly conflict in Ukraine.

While many view India’s close relationship with Russia and its unwillingness to criticise Moscow as negatives, this moment in international relations offers some opportunities as well as challenges for India’s emerging security and defence partners.

With this in mind, there are some immediate prospects for enhancing the Australia–India defence relationship by advancing the level of cooperation in two main areas, both outlined in the 2020 strategic partnership agreement. These opportunities are also in line with Australia’s main ally the United States and the triumvirate of defence agreements contained in India–US defence trade cooperation.

The first is defence commerce and technologies. Under the 2020 agreement, the defence science and technology implementing arrangement facilitates interaction between defence research organisations in Australia and India. In the past, India has shown interest in Australian defence products, including armoured vehicles, naval training simulators, mobile medical facilities and water purification.

The implementing arrangement could be expanded to include collaboration between the partners’ government scientific agencies, industry and universities on applied sciences, with a particular focus on the military sphere. Sectors of interest include defence electronics, autonomous systems, space, hypersonics and underwater systems. Both countries are keen to improve their level of defence commerce and technology cooperation, and there is considerable scope for a deeper level of collaboration.

Second, the Australia–India mutual logistics support arrangement provides enormous capacity for closer military ties, particularly in the Indian Ocean region. It will augment military interoperability and enable more complex military-to-military engagement, with the opportunity to also improve regional humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. In 2020, then-defence minister Linda Reynolds said the arrangement ‘paves the way for greater cross-service military activity, building on the success of our most complex exercise to date, AUSINDEX 2019, which focused on anti-submarine warfare’.

Importantly, the logistics arrangement enables the Australian and Indian militaries to resupply each other, which has the potential to extend the regional operational scopes of both countries. The Australian and Indian navies used it to conduct a replenishment at sea for just the first time only recently. Its use could increase in bilateral and multilateral exercises such as AUSINDEX and the annual Malabar exercises held between the Quad countries.

With agreements for defence industry and logistics now in play, Australia and India could also pursue a security communications agreement in line with what the US and India have done since its 2016 designation as a US major defence partner.

International turmoil creates as many opportunities as it does risks. Now is the time for New Delhi and Canberra to build on their comprehensive strategic partnership by diversifying and deepening their defence relationship, albeit in a relatively small way for New Delhi, thus providing further impetus to broaden the bilateral relationship and maintain stability in the region.

As NATO and Russia edge ever closer to conflict in Ukraine, a popular view is that any direct encounter between them will almost inevitably lead to nuclear war. Certainly, that’s the line that Russian President Vladimir Putin is spinning. In fact, history shows that there may be a lot of space for nuclear-armed adversaries to fight a limited conventional war without using nuclear weapons.

During the Cold War, many policymakers grew accustomed to the view that nuclear-armed adversaries would go to great lengths to avoid direct conventional military provocation for fear of escalation to a nuclear exchange. But at the same time, nuclear strategists believed that nuclear weapons could embolden challengers to take more and more risks underneath the nuclear shadow. In nuclear-war theory, this is called the ‘stability–instability paradox’.

The famous Cold War nuclear strategist Glenn Snyder argued that, while the fear of mutually assured destruction can create stability at a strategic level, nuclear weapons can simultaneously create instability by enabling lower levels of violence. In other words, creating a nuclear ceiling that both sides don’t wish to breach can provide considerable space for conflict beneath that ceiling.

The size of the space for non-nuclear conflict between nuclear powers is dependent on the circumstances and the countries involved. American political scientist Robert Jervis, for example, argued that challengers would be much more likely to engage in nuclear risk-taking, including the use of asymmetrical strategies against status quo powers.

For the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War, this instability took the shape of numerous proxy wars between them across the globe, although the two countries were also generally careful to avoid direct conventional conflict between their military forces.

Although the Soviet military was deployed to assist local forces against the US and its allies in the Korean War (pilots) and Vietnam War (technical advisers), they mostly kept a low profile. Similarly, in the 1980s the US and UK quietly deployed small numbers of special forces to Afghanistan to train mujahideen in the use of anti-aircraft missiles, but (as far as we know) they didn’t engage in direct combat.

Yet the post–Cold War experience is that nuclear-armed adversaries are becoming increasingly willing to undertake large-scale conventional and sub-conventional conflicts directly with each other.

South Asia has long been called ‘the most dangerous place on earth’ because of the frequent nuclear sabre-rattling between India and Pakistan. But the two countries have also fought several wars and other conflicts in the 25 or so years since they became declared nuclear-weapon states.

This included the 1999 Kargil War which involved the incursion into Indian territory by some 5,000 Pakistani troops and paramilitaries, opposed by 20,000 Indian troops and the air force. At least 700 Pakistani and 500 Indian troops died in fighting before Pakistan withdrew.

Pakistan has also sponsored numerous terrorist attacks against India, including the 2001 attack on the Indian parliament and the bloody assault on Mumbai in 2008 that left some 175 dead. Pakistan has long been the challenger and nuclear risk-taker in these conflicts. India, the status quo power, had to ‘suck it up’ against these attacks, keeping its conventional responses to a minimum.

In recent years, though, India has been far more willing to conduct kinetic operations against its nuclear adversary. This included the so-called surgical strike by Indian special forces against terrorist bases in Pakistan following the 2016 Uri terrorist attack and missile strikes against Pakistani territory following the 2019 Pulwama terrorist attack. In the Pulwama case, despite nuclear rhetoric from both sides, the kinetic actions were followed by a delicate dance between the two countries to de-escalate.

And it’s not just India and Pakistan. In June 2020, Indian and Chinese troops engaged in a brief but bloody fight, the first major conflict on the Himalayan border since they both became nuclear-weapon states. Then, an attack initiated by Indian troops (without weapons) on a newly built Chinese outpost in Ladakh was met with a forceful and deadly response when an estimated 20 Indian troops were bludgeoned to death with clubs and rocks. The Chinese side suffered 35 casualties, according to US sources. The Indian army has since been authorised to use weapons against Chinese forces.

What all this means for NATO and Russia in Ukraine isn’t entirely clear. For their part, the US and its NATO allies have so far been careful to keep the Ukraine war as essentially a proxy conflict, supplying defensive weaponry but ruling out using airpower to enforce a no-fly zone over Ukraine.

But pressure for greater intervention will grow as the conflict continues, including the possible wholesale destruction of major Ukrainian cities by Russian forces, the potential release of radiological materials from nuclear power plants, or even the intentional use of chemical weapons by Russian forces. Options for NATO could include deploying military advisers or ‘international brigades’ of volunteers. There may also be calls for the deployment of troops to enforce humanitarian corridors for the evacuation of civilians from the besieged cities.

In the meantime, Putin has been doing what he can to play up the nuclear threat against NATO, just as Pakistan has done against India for some 25 years. NATO, as a coalition of status quo powers (only three of which have nuclear weapons), will be sorely put to the test by Russia, the challenger and nuclear risk-taker.

The death of Indian General Bipin Rawat in a helicopter crash last month may have far-reaching consequences for the Indian military and its defence partnerships with the United States, Japan and Australia under the Quad.

Rawat was India’s first chief of defence staff, a position established to oversee reforms to the military and the civilian–military bureaucracy. He took up the role in January 2020 after serving as India’s top army officer during a period marked by targeted and punitive Indian military action against Pakistan and China.

However, his most important role as chief of defence staff was to drive the largest restructuring ever undertaken of the Indian military, unpacking its overcomplicated command structure and promoting coordination between its three services.

The Indian military’s push to modernise and to make its three services truly interoperable has strong implications for the Indo-Pacific. At present, the Indian military operates under an orthodox doctrine with a focus on capturing territory or using large army formations to impose punitive costs on an enemy. The doctrine has served India well during wartime, including in the ongoing border crisis with China, in which India gained an advantage by capturing sensitive mountainous areas that it used as leverage during negotiations.

But the doctrine has encouraged development of a military structure that prioritises India’s continental border, with most of the defence budget spent on maintaining a large physical and deterrent presence along the disputed borders with Pakistan and China. This has come at the cost of investing in India’s presence in the Indian Ocean—the navy remains the most underfunded service.

Much-needed structural reforms to deal with modern and non-traditional threats like cyber and grey-zone challenges have also been delayed.

The Indian military currently functions with a complex command structure. Seventeen service-specific commands are divided into overlapping geographical areas, and sometimes the services’ commands overlap. The only tri-service command is located in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, overlooking an important maritime choke point at the mouth of the Malacca Strait.

This complicated command structure means the Indian military lags behind defence partners, such as the US military and India’s direct competitor, the Chinese military, when it comes to ensuring that all military services operate under joint theatre commands covering a geographic or thematic area.

The post of chief of defence staff was created to address this problem by overseeing the creation of joint theatre commands integrating all three military services.

As the first appointee to the post, Rawat was at a unique position. He enjoyed the confidence of the political leadership, he had strong military experience in dealing with threats at the border and insurgency, and he was singularly focused on fast-tracking reforms.

A few months before his death, Rawat publicly shared details of the shape of the proposed joint theatre commands for the first time. India would create four theatre commands, one responsible for the border with Pakistan, another covering the now active border with China, a maritime command responsible for the Indian Ocean region, and the existing command in the Andamans looking at the eastern Indian Ocean. Two potential commands for the air force and cyber warfare were also in the works.

Besides promoting interoperability and integrating India’s command structure to effectively deal with dual border threats from China and Pakistan, the establishment of a dedicated maritime command would significantly improve the navy’s power projection in the Indian Ocean region and its maritime partnership with the Quad.

India would, for the first time, elevate the importance of the maritime theatre to match its traditional focus on land borders.

India’s unique position in the Indian Ocean region—overlooking crucial maritime trade routes and strategic choke points—gives it a traditional geographical advantage. But to counter China’s increasing presence, India needs to invest in increasing its ability to project maritime power. A maritime theatre command could act as a force multiplier, with the three services combining assets to effectively manage China’s rising footprint in the Indian Ocean while simultaneously boosting their capabilities in surveillance and disaster management.

This would reinforce India’s position as the resident Indian Ocean power in the Quad and bolster options for maritime cooperation. The added investment in the Andaman and Nicobar Command would help promote surveillance cooperation among Quad partners at the mouth of the strategic Malacca Strait. Knowledge sharing on joint operations concepts within the Quad or bilaterally between India and Australia could also be an avenue for stronger defence cooperation.

The Indian system is resilient. India has already begun searching for its next defence chief, but the decision is likely to be delayed. The nature of the post means that defence reforms will go through regardless of who succeeds Rawat. But the successor and political leadership should ensure that the urgency and pace of reforms under Rawat are maintained and that the elevation of the maritime theatre isn’t delayed. Further delays would have grave implications for the balance of power in the Indian Ocean region.

The end of 2021 may prove to be an important milestone in the evolution of strategic relations between Russia and India. On 6 December, Russian President Vladimir Putin flew into New Delhi on a one-day state visit. The one-on-one meeting with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, which lasted three and a half hours, was aimed at restoring confidence between the two powers as time-proven and trusted strategic partners.

For Putin, the trip to India was only his second overseas visit since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic (the other was the first meeting with his US counterpart Joe Biden in Geneva). That fact alone signifies the importance of India to the Kremlin and the desire to keep relations close. But Putin’s brief visit to New Delhi was just part of broader high-level bilateral talks, which included an impressive entourage representing both countries.

The last time Putin and Modi met was in 2019 during the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok. After that, the two leaders paused their interactions. The reason, they claimed, was the Covid-19 outbreak.

The relationship had been cooling long before Covid-19 struck, however. New Delhi felt that Moscow was taking advantage of India, playing upon its fears of China. The case of India’s purchase of a modified Russian cruiser turned aircraft carrier is one example. It led India’s comptroller and auditor-general to lament that India had paid 60% more for a second-hand aircraft carrier than a new one would have cost. Admiral Arun Prakash, a former chief of the Indian naval staff, was equally scathing in his evaluation of the Russian MiG-29K aircraft that were to be used on the aircraft carrier.

Russia, for its part, was unhappy with India’s growing ties to the US. Between 2007 and 2020, India spent more than US$17 billion on military purchases from the US. Russia was particularly unhappy that India had entered into four ‘foundational’ security agreements with the US that cover the transfer of military information, logistics exchanges, compatibility and security.

At the same time, Russia’s relationship with China was growing through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and its ties to the Collective Security Treaty Organization, which was established to ensure the security of the Soviet Union’s successor states. Russia and China, seeing the US as a common antagonist, collaborated on technology transfers, Russia’s sale of energy products to China, and increased trade and tourism. They have engaged in joint military exercises and naval and air patrols.

That said, there remains the suspicion that Moscow is ‘passively facilitating’ New Delhi’s role in the Quad in order to restore equality in its strategic relations with Beijing. That could help revive, in turn, its stalled ‘new détente’ with the West.

India is suspicious of Russia’s developing relationship with Pakistan. New Delhi worries that Moscow is hyphenating its relationships with its two neighbouring enemies. That suspicion grew when Russia didn’t invite India to a meeting it convened with China, Pakistan and the US on the Afghanistan situation, a move that was seen as a deliberate snub in New Delhi.

India needs the potential security that Russia can provide. Little wonder, then, that it was prepared to purchase the S-400 air-defence system from Russia despite US pressure not to, and to offer an invitation to Putin to visit India, which he accepted.

The visit generated several important outcomes.

The two countries launched ‘2+2’ ministerial consultations involving their foreign and defence ministers, making Russia the fourth partner with which India has the same format (the other three are the other Quad members: Australia, Japan and the US).

They also signed another 10-year agreement on joint military–technical cooperation until 2031 and agreed to expand and deepen bilateral defence cooperation. Adding to that, Russia has reaffirmed its position as one of the principal providers of advanced military technology to the Indian military. Since 1991, India has acquired a comprehensive suite of weapons and platforms for all its fighting services worth some US$70 billion. The current value of India’s defence contracts with Russia is approximately US$15 billion.

The target of US$30 billion in annual trade by 2025, which was set in 2019, was confirmed.

Perhaps one of the most important outcomes for Russia was India’s reassurance that it is not siding with US strategic plans to form a regional political–military containment bloc. According to Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, the Indians ‘distanced themselves from the AUKUS bloc’. He said, ‘They are part of the Quad group, which brings together India, Japan, Australia and the US, and India … emphasises its interest in economic infrastructure and transport projects within this framework.’

Clearly, though, the talks didn’t eradicate all contentious points in the relationship. India is likely to remain concerned about Russia’s ties to China, Pakistan and the Taliban. Despite ambitious goals, the bilateral economic relationship won’t reach the levels of the ones that India enjoys with the US and China.

Even in the defence cooperation sphere, which is at the core of Russia–India strategic ties, some issues persist. For example, the two countries failed to finalise the reciprocal logistics support agreement, which was supposed to become an important stepping stone in closer military-to-military interaction.

On the other hand, the meetings highlighted the special nature of Russia–India strategic relations as well as mutual will to keep nurturing them.

The meetings in New Delhi came less than a week after the visit to Moscow of the president of Vietnam, a country with which Russia developed a comprehensive strategic partnership a decade ago. Both events highlight Russia’s more flexible approach towards its strategic engagement in the Indo-Pacific, despite the centrality of China in Russia’s Asia policy.

Putin’s meeting with Modi also happened to take place a day before the Russian president had his second major interaction with Biden, and just days before the US-led Summit for Democracy, to which Moscow was not invited. For Putin, it was important to show Washington and Brussels that Russia has a network of strategic partners it can call upon.

Recognising that and Russia’s importance to India, New Delhi has tried to show Moscow that it’s not drifting away from the relationship. New Delhi recognises that Moscow can’t fully trust Beijing, which makes the Indo-Russian relationship all the more important. India’s purchase of the S-400 missile system despite US pressure was meant to send exactly that message. The launch of the 2+2 ministerial consultations is likely to ease Russia’s concerns that New Delhi has been gradually drifting towards the US geopolitical orbit, confirming that India is ‘not in anyone’s camp’.

India has somehow emerged as the villain of last month’s United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), blamed for resisting cuts to coal consumption even as toxic air envelops its capital, New Delhi. The country’s supposed crime in Glasgow was to join China in insisting on a last-minute change to the conference’s final declaration, in which countries pledged to ‘phase down’ rather than ‘phase out’ coal. For that, India, whose per capita carbon-dioxide emissions are a fraction of those of the world’s leading emitters, was widely criticised for obstructing the global fight against climate change.

The irony is that India has done far less to intensify the planet’s greenhouse effect than either China or the developed West. True, the country is a major coal consumer, and derives about 70% of its energy from it. But, as recently as 2015, at least a quarter of India’s population couldn’t take for granted what almost everyone in the developed world can: to flick a switch on a wall and be bathed with light.

Worse, Indians are among the biggest victims of climate change, periodically enduring devastating floods and unseasonal droughts, in addition to choking on polluted air. Delhi is a poster child for poor air quality, which hovers between ‘severe’ and ‘hazardous’ for much of the year. The causes include PM2.5 particles emitted from coal-fired power plants, fumes from dense traffic, industrial pollution and the burning of crop stubble by farmers in neighbouring states—all combined with winter fog.

But given India’s traditional role as a leading voice of the developing world, it became the face of the last-minute change of language at COP26. The ‘phase down’ wording regarding coal consumption had already appeared in a US–China bilateral climate agreement signed earlier in the conference. Nevertheless, India became the focus of global opprobrium.

India does not deserve to be the fall guy. For starters, the country has 17% of the world’s population but generates only 7% of global CO2 emissions. (China, with 18.5% of the world’s people, generates 27% of emissions, and the US, with less than 5% of the world’s population, accounts for 15%.) Whereas wasteful consumption and unsustainable energy-guzzling are rife in the West, most Indians live close to the subsistence level, and many have no access to energy. To expect India to meet the targets that rich countries currently tout is unfair and impractical.

Economic development—indispensable to pulling millions of Indians out of poverty—requires energy. Coal may be polluting, but it is not feasible for any developing country to switch rapidly to cleaner alternatives that need scaling up.

And despite having vast financial resources and access to cleaner fossil fuels such as natural gas (which India must import), Western countries have done little to help. They have failed to keep climate-finance promises to poor countries (notably the US$100 billion per year they committed to provide at COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009), and refused to transfer advanced green technologies. And COP26 singled out the coal used largely by developing countries, not the oil and gas used extensively in the West.

India’s energy requirements are expected to increase faster than those of any other country in the next two decades. Since COP21 in Paris in 2015, India has announced ambitious plans to scale up its production and use of renewable energy, which currently accounts for only 18% of its electricity generation. And at COP26, India complemented its explicit commitment to phase down coal with a pledge to achieve net-zero emissions by 2070.

India has also updated its nationally determined contributions, which it must fulfill by 2030. The country is now pledging to increase its installed renewable-energy capacity to 500 gigawatts, and meet 50% of its energy requirements from non-fossil-fuel sources. India also aims to reduce its CO2 emissions by one billion tons and lower its emissions intensity (which measures emissions per unit of economic growth) by 45% from 2005 levels.

For now, there is no viable alternative to coal. Blessed with abundant sunshine, India has become a solar-power enthusiast and plans to generate 40 gigawatts of green energy from rooftop solar installations by 2022. But it has achieved barely 20% of that target so far. Vast amounts of solar energy cannot be generated overnight and battery storage remains expensive, while green hydrogen technology and facilities are still unavailable in India. Its wind energy is minuscule, and the country lacks significant oil and gas reserves. Nuclear power accounts for less than 2% of India’s electricity, and nuclear plants constantly face opposition from residents of surrounding areas.

As a result, India’s performance on greenhouse-gas emissions will get worse before it gets better. According to a study by BP, India’s share of global emissions will increase to 14% by 2040. Coal will by then account for 48% of the country’s primary energy consumption and renewable energy only 16%. And because of India’s high dependence on agriculture, which engages nearly two-thirds of its population, and its vast number of cattle, the country did not sign the global deal announced at COP26 to reduce methane emissions.

Of course, reducing emissions is not the only way to combat climate change. India plans to bring a third of its land area under forest cover, and to plant enough trees by 2030 to absorb an additional 2.5–3 billion tons of atmospheric CO2. It has made a start, with forest cover increasing by 5.2% between 2001 and 2019, though progress has been uneven, with the northeast losing forest cover while the south visibly improves.

Still, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that achieving global net-zero emissions by 2050 is the minimum needed to limit global warming to 1.5° Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Climate Action Tracker calculates that—based on countries’ current 2030 climate targets—the world is heading for a temperature rise of 2.4°C by 2100. Some scientists warn that global warming could eventually exceed 4°C.

If this happens, the resulting heat waves, droughts, floods and rising sea levels would cause devastating loss of human life, mass extinction of animal and plant species, and irreversible damage to our ecosystem. India would be a major victim of such a calamity. The country will therefore make a good-faith effort to help avert climate disaster—but only within the limits of what it can feasibly do.