Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Rarely have two major democracies descended into as ugly a diplomatic spat as the one now unfolding between Canada and India. With the traditionally friendly relationship already at its lowest point ever, both sides are now engaging in quiet diplomacy to arrest the downward spiral, using the United States, a Canadian ally and Indian partner, as the intermediary. But even if the current diplomatic ruckus eases, Canada’s tolerance of Sikh separatist activity on its territory will continue to bedevil bilateral ties.

The latest dispute began when Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau sensationally claimed that there were ‘credible allegations’ about a ‘potential link’ between India’s government and the fatal shooting in June of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a Sikh separatist and Canadian citizen, on Canadian soil. India’s government fired back by demanding that Canada reduce its diplomatic staff in India, suspending new visas for Canadians, and accusing Canada of making ‘absurd’ accusations to divert attention from its status as ‘a safe haven for terrorists’.

Nijjar was hardly the only Sikh separatist living in Canada. In fact, the country has emerged as the global hub of the militant movement for ‘Khalistan’, or an independent Sikh homeland. The separatists constitute a small minority of the Sikh diaspora, concentrated in the Anglosphere, especially Canada. Sikhs living in India—who overwhelmingly report that they are proud to be Indian—do not support the separatist cause.

With British Columbia as their operational base, the separatists are waging a strident campaign glorifying political violence. For example, they have erected billboards advocating the killing of Indian diplomats (with photos), honoured jailed or killed terrorists as ‘martyrs’, built a parade float on which the assassination of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was re-enacted, and staged attacks on Indian diplomatic missions in Canada. They have also held referendums on independence for Khalistan in Canada.

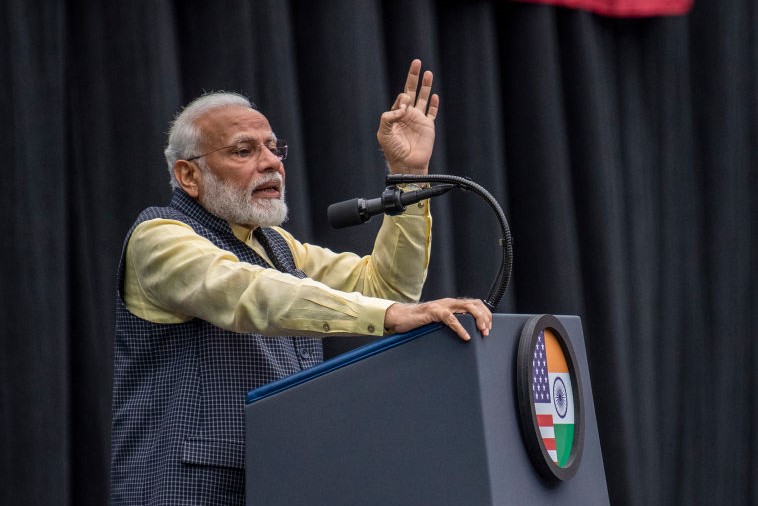

But, much to India’s frustration, Canada has been reluctant to take strong action to rein in Sikh separatism. Trudeau’s first official visit to India in 2018 turned into a disaster after it was revealed that a convicted Sikh terrorist who had spent years in a Canadian prison following the attempted assassination of a visiting Indian state cabinet minister had made it onto the Canadian guest list. At last month’s G20 summit in New Delhi, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi gave Trudeau a dressing-down for being soft on violent extremists.

It was against this tense backdrop that Trudeau made his allegations about Nijjar’s murder. When countries have linked foreign agents to a domestic death—for example, in 2010, when the Dubai police chief accused Mossad, Israel’s intelligence service, of killing a Hamas commander in a local luxury hotel—they have typically presented video, audio or forensic evidence. And they have mostly avoided blaming the government that the foreign agents represent.

Trudeau, by contrast, cast blame directly on the Indian government without presenting a scintilla of evidence. He says the allegations are based on credible intelligence, apparently from a Five Eyes partner country (Australia, New Zealand, the UK or the US), but refuses to declassify the information or share it with Indian authorities.

Trudeau apparently hasn’t provided ‘any facts’ even to Canadian opposition leader Pierre Poilievre, a member of the Privy Council. And, according to the premier of British Columbia, the province where the killing occurred, the intelligence briefing he received on the matter included only information ‘available to the public doing an internet search’.

Meanwhile, Canadian investigators haven’t made a single arrest in the case. This has left many wondering to what extent Canada’s powerful but unaccountable intelligence establishment controls the country’s foreign policy.

In any case, there’s no doubt that Sikh radicals wield real political influence in Canada, including as funders. Trudeau keeps his minority government afloat with the help of Jagmeet Singh, the New Democratic Party’s Sikh leader and a Khalistan sympathiser. According to a former foreign policy adviser to Trudeau’s government, action was not taken to choke off financing for the Khalistani militants because ‘Trudeau did not want to lose the Sikh vote’ to Singh.

Canada must wake up to the threat posed by its Sikh militants. Rising drug-trade profitability and easy gun availability in British Columbia have contributed to internecine infighting among Khalistan radicals in the province. The volatile combination of Sikh militancy, the drug trade and gangland killings has serious implications for Canadian security, but it is not only Canadians who are in danger.

Under the premiership of Trudeau’s father, Pierre Trudeau, Canada’s reluctance to rein in or extradite Sikh extremists wanted in India for terrorism led to the 1985 twin bombings targeting Air India flights. One attack killed all 329 passengers, most of whom were of Indian origin, on a flight from Toronto; the other misfired, killing two baggage handlers at Tokyo’s Narita Airport. With Khalistani militants continuing to idolise Talwinder Singh Parmar—the terrorist that two separate Canadian inquiries identified as the mastermind behind the bombings—history is in danger of repeating itself.

By reopening old wounds, not least those created by the Air India attacks, Trudeau’s accusations have created a rare national consensus in fractious and highly polarised India. Many are calling for New Delhi to put sustained pressure on Ottawa to start cleaning up its act. But more bitterness and recriminations won’t restore the bilateral relationship. For that, both sides must use effective, cooperative diplomacy to address each other’s concerns.

Justin Trudeau’s announcement that Canadian authorities suspect India had some role in the killing of Sikh separatist leader Hardeep Singh Nijjar outside a temple in Surrey, British Columbia on 18 June was dramatic, but hardly unexpected. The Canadian media began speculating about India’s possible involvement soon after Nijjar’s murder, prompted by leaks from the intelligence services. Other media outlets quickly connected the case to the untimely deaths of two other Sikh activists. Avtar Singh Khanda led a violent protest outside the Indian High Commission in London in March and died a few days before Nijjar, and Paramjit Singh Panjwar was shot by unidentified gunmen in Lahore, Pakistan, in May.

New Delhi has rejected Trudeau’s claims, but this issue is not going to go away. Nor is it likely to remain within the bounds of the Canada-India relationship. Given the patchy and contested information we have at this point, what might Australia learn from the Nijjar affair and how should Canberra respond?

The first thing to note is that Khalistani activism overseas—not just in Canada, but also in the United Kingdom, United States and Australia—is a major concern for New Delhi, not a marginal one, as some governments might think. The drivers of this concern are mixed. Senior figures in the Indian government, not least national security advisor Ajit Doval, experienced the brutal Khalistani-driven Punjab insurgency of the 1980s and 90s first hand. They would likely favour a hard-line approach. So too might more cynical elements of Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party who might seek to frame Khalistani activism as a threat, as they have in recent years, and consolidate political support with a tough response.

The second lesson is that whatever has occurred in this particular case, India has long since shed its earlier adherence to ‘strategic restraint’. Even if New Delhi played no role in Nijjar’s killing, as it insists, it is nevertheless clear that India is willing to use force and take risks to defend its interests. The special forces raid into Pakistani-administered Kashmir in 2016 and an airstrike on alleged terrorist camps in Pakistan-proper in 2019 were clear demonstrations of this new approach. So too were the premeditated encounter with Chinese soldiers in the Galwan Valley in mid-2020 and the rapid deployment of tens of thousands of troops into the Himalayas in the weeks that followed.

The third issue is that this muscularity is popular within India and segments of the Indian diaspora overseas. In the 2019 election campaign, Modi portrayed himself as a humble but vigilant chowkidar (‘watchman’) for a reason: it resonated with voters who want to see India standing up for itself in the world and accorded the respect the country deserved. For that reason, New Delhi’s indignant response to Canada’s accusations concerning Nijjar’s killing has bipartisan support, and strong defenders in leading media outlets.

The fourth takeaway is that states like Australia must pay closer attention to the politics of the Indian diaspora because New Delhi certainly does. Rightly, Canberra has long emphasised that the diaspora can and does play a crucial role in developing economic ties with India and improving cultural understanding, as well as making a substantial and valued contribution to Australian society. But it must also be recognised that the Indian diaspora is highly political. It is as deeply engaged in the politics of India as in the politics of the countries in which the diaspora has settled.

In Australia alone, both left-wing and right-wing activism flourishes in the Indian-origin community and Khalistani separatism has lately become popular among some Sikhs. For these reasons, India is more interested in monitoring and sometime intervening in diaspora politics than other countries, and this demands careful management.

Australia’s response to the Nijjar affair must take account of all four points—and focus on our interests, not on airy talk about supposed shared values. If it has not done so already, Canberra must clearly convey to New Delhi that while it must uphold freedom of speech and association within Australia, it takes India’s concerns about militancy within the Khalistani movement seriously.

At the same time, Canberra must send the message that while Australia views a stronger, more capable, and less restrained India as a net positive for regional stability, it does not see an India that intimidates overseas activists or engages in extra-judicial executions in the same way. This must be done firmly but with tact, recognising that many Indians want to see their government deal robustly with people they see as dangerous terrorists harboured by a complacent or complicit West, and acknowledging that the West’s recent record in counterterrorism is, at best, patchy and morally compromised.

Canberra cannot neglect the diaspora. Australia’s sizable and growing Indian-origin community must be reassured in clear terms that the rights and freedoms of all Australian citizens and residents will be upheld. In parallel, diaspora activists across the political spectrum should be engaged to ensure both the proper boundaries of political action and our foreign interference regime are understood, even when disagreement is keen and debate fraught, as it so often is.

India is too important in itself and in terms of the role it plays in the wider region to allow Australia’s relations with New Delhi to deteriorate to where Canada’s ties now lie. Our security and prosperity are bound up with India’s success. But our partnership can only progress if there’s mutual respect of each other, our respective interests, and agreed rules and norms. This should be our focus as this affair plays out.

Wargaming has returned to the fore as a tool for military planning. US think tanks are outcompeting each other in wargaming a Taiwan contingency, with their recommendations amplified by mainstream media. One recent war game even made congressional representatives act as US National Security Council members in a Taiwan contingency.

The potential benefits of wargaming are historically evident, even if their full impact is still debated. Many war games are essentially geared towards military scorecard comparisons and warfighting, with the objective of collecting information on the likely use of weapons systems within a set of strategic choices.

But such games tend to have limited engagement with the larger political context. The road to war is often left unexamined when games begin with the assumption that a political decision for war has already been made. The political objectives for the hypothesised military operation are assumed to be relatively fixed and unidimensional.

Understandably, perhaps, many games are geared towards making useful and timely interventions in the debates on the US’s warfighting capabilities and options in a Taiwan contingency.

India lags in wargaming and should develop a culture of strategic wargaming. But the type of war game that’s prominent in the West may have limited value for India, particularly in examining potential conflicts with China in the Himalayas.

For one thing, compared with other countries, India’s political system is characterised by ‘absent dialogues’, between civilians (politicians and bureaucrats) and the military, and between the government and its people. This, combined with limited access to information, make it difficult to build war games aimed at deducing likely outcomes of a conventional war between India and China or Pakistan.

In addition, Indian analysts generally don’t seriously consider an all-out war against China as an option. The unfavourably skewed military balance combined with geographic disadvantages imposes costs that are considered too prohibitive to accept. Political considerations, in part related to historical memory and self-identity, make the prospect of a defeat in any such war all the more unbearable.

Rather, India’s security challenges are usually conceived in terms of political crises surrounding military contingencies such as transgressions and military coercion by China. India’s cognitive energies are geared towards establishing conventional minimal deterrence vis-à-vis China, which also relies on appeals to China’s own broader strategic interests. In contrast, US strategic priorities pertain to coalition warfighting to deter rising Chinese assertiveness in the entire Indo-Pacific region.

But in understanding a potential conflict in the Himalayas, straightforward bean counting or even more nuanced assessments of military capabilities may miss important variables in decision-making and responses. Analyses of long-term trends are useful and indispensable guides but can suffer from inductivism and may ill-prepare us for strategic surprise—such as Chinese actions in May 2020. Well-designed war games have the potential to combine analysis and military empirics to uncover unthought-of pathways, drivers and contingencies.

The military balance should be understood in conjunction with the particular ways through which a crisis evolved towards war. Hence, an understanding of the nature of the crisis and its history and elite perceptions of political realities are indispensable for a fuller understanding of the architecture of the India–China flashpoint in the Himalayas. Crises occur primarily in the minds of human agents, which is why war games are a valuable tool to understand the contours of a future crisis as it looks in the minds of decision-makers.

The evolving crisis in the Himalayas poses tough questions for the Indian strategic community, which remains confused about Chinese objectives and strategy.

In recent months, the US administration and strategic community have registered a greater interest in the stand-off between India and China in the Himalayas as an emerging flashpoint with global implications. The US is making a cognitive shift from supporting bilateral dialogue to resolve the crisis to assessing China’s continuing military build-up and coercion of India. But US decision-makers also struggle to understand what is driving the border conflict or how it could end.

Simulation exercises and wargaming would assist India and its partners to better anticipate strategic decisions and prepare responses to various pathways. A recent report recommends that Delhi and Washington ‘hold joint wargaming exercises to develop mutual understanding of the threat of a future India–China conflict and identify Indian capabilities gaps that can be filled before conflict breaks out’. Another thoughtful analysis recommends discussing escalation-driven crisis scenarios with Quad members to enable ‘red-teaming of India’s escalatory assumptions, as well as its proposed off-ramps, to support Delhi’s escalation-control efforts ahead of time’.

But cooperation in wargaming between India and its like-minded partners will require translation of differing strategic concerns to reflect India’s unique needs and approaches. Wargaming should be a flexible tool that emphasises scenarios that are principally political, but with strong military arbitration.

These war games should also emphasise scenario-building to help unpack the slow and winding road to a severe crisis and then, possibly, war. Given the political nature of the crisis, such exercises could face significant challenges when conducted at an official level, meaning that academic institutions and think tanks can play a valuable role.

With these objectives in mind, I, with the assistance of senior retired military officers, design war games for the Council for Strategic and Defense Research in New Delhi. These games have generated valuable insights by encouraging vigorous debate of interpretations and responses. Conditions are also created to allow for back-channel negotiations to assess likely dynamics between military developments and civil negotiations.

Also valuable are have been role-play-driven insights on possible Chinese perceptions of the larger border crisis as well as Beijing’s more immediate reasons for undertaking the May 2020 military operations. Intra-team negotiations can also be used to interrogate unspoken assumptions on each side.

It may seem surprising that a wargaming culture hasn’t taken off in India given its acute security challenges and strategic aspirations. As part of managing a rising China in its own backyard, India will have to reduce perception gaps that exist between it and its like-minded partners. Increasing engagement in jointly designed wargaming exercises that permit free thinking and force players to reckon with difficult choices is one way to do so.

This article was written as part of the Australia India Institute’s defence program undertaken with support from the Department of Defence. All views expressed in this article are those of the author only.

China’s sharp economic slowdown has raised alarm bells around the world. But it has also thrown into relief the rise of another demographic powerhouse next door. The Indian economy grew at an impressive 7.8% annual rate in the second quarter of 2023, and the country recently reached an important milestone by becoming the first to land a spacecraft on the moon’s potentially water-rich south pole. And, India’s ascent, unlike China’s, hasn’t been accompanied by an increasingly assertive foreign policy or an appetite for other countries’ territory.

As India’s geopolitical, economic and cultural clout grows, so does its global footprint. China’s ‘decline’, as some have begun to call the conclusion of the country’s four-decade-long economic boom, opens new opportunities for the Indian economy and other developing and emerging countries.

Earlier this year, India reached another milestone when its population officially surpassed that of China, which had been the world’s most populous country for more than 300 years. While China’s shrinking, rapidly ageing population is likely to impede economic growth and may curtail Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions, India—one of the world’s youngest countries, with a median age of 28.2—is poised to reap a huge demographic dividend.

But the driving force behind India’s emergence as a major global power is its rapid economic growth. While India’s GDP is still smaller than China’s, the country is the world’s fastest-growing major economy and is projected to account for 12.9% of global growth over the next five years, surpassing the United States’ 11.3% share.

In addition to fuelling a consumption boom, India’s youthful population is also driving innovation, as evidenced by the country’s world-class information economy and its recent moon landing, which the country managed to achieve despite a national space budget equivalent to roughly 6% of what the US spends on space missions. Having already surpassed the United Kingdom, its former colonial ruler, India is poised to overtake Japan and Germany to become the world’s third-largest economy by 2030, behind the US and China.

Given its increasingly unstable neighbourhood, it should come as no surprise that India has the world’s third-largest defence budget. The deepening strategic alliance between China and Pakistan underscores India’s precarious position as the only country bordering two nuclear-armed revisionist states with expansionist ambitions. For the past three years, India has been locked in a tense military standoff with China along its Himalayan border. Bilateral relations, marked by intermittent clashes in the disputed Tibet–Ladakh border region, are at their lowest point in decades.

By confronting China despite the risk of a full-scale war, India has challenged Chinese power in a way no other country has done in this century. But despite leaning towards forging closer ties with the West, India remains hesitant to enter into formal military alliances with Western countries.

Western powers are partly to blame. US President Joe Biden’s reluctance to comment on the Sino-Indian military standoff, let alone openly support India, has sent a clear signal that India is responsible for its own defence. Given that the country’s future growth hinges on its ability to defend itself against external threats, India will likely step up its efforts to modernise its conventional armed forces and enhance its nuclear deterrence.

The escalating geopolitical rivalry between China and India could also impede efforts to unite the global south and transform the BRICS group into a credible alternative to the G20 and G7. The BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) recently agreed to expand the group by adding six new members: Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Ethiopia, Argentina and Iran. Given the 11 members’ divergent interests, BRICS+ will likely find it even harder to reach consensus on any major issue.

Meanwhile, China’s economic slump could prompt President Xi Jinping to double down on his expansionist agenda. Biden recently characterised the stagnating Chinese economy as a ‘ticking time bomb’, warning that, ‘When bad folks have problems, they do bad things.’ China’s controversial new national map, which depicts vast areas of India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan and Bhutan (and even a bit of Russia) as Chinese territory, underscores the threat posed by Beijng’s increasingly aggressive behaviour.

In addition to these external threats, India’s future will be shaped by its response to domestic economic challenges. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has made great strides in modernising the notoriously outdated Indian bureaucracy and promoting e-government to reduce red tape and attract foreign direct investment. His government has invested heavily in upgrading and expanding the country’s infrastructure, implemented regulatory reforms and sought to boost domestic manufacturing through the ‘Make in India’ initiative. But to transform itself into a global manufacturing hub, India must invest in human capital, particularly in education and training.

India’s size and diversity also pose enormous challenges. India may be the first developing economy that, from the beginning, has pursued modernisation and prosperity through a democratic system. But as one of the world’s most culturally diverse countries, its seemingly never-ending election cycle has often fuelled division and polarisation.

But, despite its US-style polarised politics, India’s democratic framework has served as a pillar of stability. By fostering open expression and dialogue, the Indian political system has empowered grassroots communities and individuals, enabling members of historically marginalised classes and castes to rise to the highest levels of policymaking.

Whether India can maintain its upward trajectory will depend on its ability to maintain political stability, rapid economic growth, domestic and external security, and a forward-looking foreign policy. Success would enhance India’s global standing and help advance US interests in the Indo-Pacific, the world’s new geopolitical fulcrum and home to its fastest-growing economies.

In March 1985, the Wall Street Journal showered India’s new prime minister, Rajiv Gandhi, with its highest praise. In an editorial titled ‘Rajiv Reagan’, the newspaper compared the 40-year-old Gandhi to ‘another famous tax cutter we know’, and declared that deregulation and tax cuts had triggered a ‘minor revolution’ in India.

Three months later, on the eve of Gandhi’s visit to the United States, Columbia University economist Jagdish Bhagwati was even more effusive. ‘Far more than China today, India is an economic miracle waiting to happen,’ he wrote in the New York Times. ‘And if the miracle is accomplished, the central figure will be the young prime minister.’ Bhagwati also praised the reduced tax rates and regulatory easing under Gandhi.

The early 1980s marked a pivotal historical moment, as China and India—the world’s most populous countries, with virtually identical per capita incomes—began liberalising and opening up their economies. Both countries elicited projections of ‘revolution’ and ‘miracle’. But while China grew rapidly on a strong foundation of human-capital development, India shortchanged that aspect of its growth. China became an economic superpower; projections of India as next are little more than hype.

The differences have been long in the making. In 1981, the World Bank contrasted China’s ‘outstandingly high’ life expectancy of 64 years to India’s 51 years. Chinese citizens, it noted, were better fed than their Indian counterparts. Moreover, China provided nearly universal health care, and its citizens—including women—enjoyed higher rates of primary education.

The World Bank report highlighted China’s remarkable strides towards gender equality during the Mao Zedong era. As Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn note in their 2009 book Half the sky, China (particularly its urban areas) became ‘one of the best places to grow up female’. Increased access to education and the higher female labour-force participation rate resulted in lower birth rates and improved child-rearing practices. Recognising China’s progress in developing human capital and empowering women, the World Bank made an unusually bold prediction: China would achieve a ‘tremendous increase’ in living standards ‘within a generation or so’.

Rather than tax cuts or economic liberalisation, the World Bank report focused on a historical fact recently emphasised by Brown University economist Oded Galor. Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, every instance of economic progress—the crux of which is sustained productivity growth—has been associated with investments in human capital and higher female workforce participation.

To be sure, market liberalisation greatly helped Chinese and Indian growth. But China built its successful development strategy on the twin pillars of human capital and gender equality, areas in which India has lagged far behind.

Even after it became more market-oriented, China invested impressively in its people, outpacing India in raising education and health standards to levels necessary for an internationally competitive workforce. The World Bank’s 2020 Human Capital Index—which measures countries’ education and health outcomes on a scale of 0 to 1—gave India a score of 0.49, below Nepal and Kenya, both poorer countries. China scored 0.65, similar to the much richer (in per capita terms) Chile and Slovakia.

While China’s female labour-force participation rate has decreased to roughly 62% from around 80% in 1990, India’s has fallen over the same period from 32% to around 25%. Especially in urban areas, violence against women has deterred Indian women from entering the workforce.

Together, superior human capital and greater gender equality have enabled much higher Chinese total factor productivity growth, the most comprehensive measure of resource-use efficiency. Assuming that the two economies were equally productive in 1953 (roughly when they embarked on their modernisation efforts), China became over 50% more productive by the late 1980s. Today, China’s productivity is nearly double that of India. While 45% of Indian workers are still in the highly unproductive agriculture sector, China has graduated even from simple, labour-intensive manufacturing to emerge, for example, as a dominant force in global car markets, especially in electric vehicles.

China is also better prepared for future opportunities. Seven Chinese universities are ranked among the world’s top 100, with Tsinghua and Peking among the top 20. Tsinghua is considered the world’s leading university for computer science, while Peking is ranked ninth. Likewise, nine Chinese universities are among the top 50 globally in mathematics. By contrast, no Indian university, including the celebrated Indian Institutes of Technology, is ranked among the world’s top 100.

Chinese scientists have made significant strides in boosting the quantity and quality of their research, particularly in fields such as chemistry, engineering and materials science, and could soon take the lead in artificial intelligence.

Since the mid-1980s, Indian and other international observers have predicted that the authoritarian Chinese hare would eventually falter and the democratic Indian tortoise would win the race. Recent events—China’s harsh zero-Covid restrictions, rising youth unemployment and the adverse repercussions of the Chinese authorities’ ham-handed efforts to rein in the country’s overgrown real-estate sector and large tech companies—seem to support this view.

But while China, with its deep well of human capital and greater gender equality, stands poised at the frontiers of both the old and the new economies, Indian leaders and their international counterparts tout an ahistorical ability to leapfrog over a fragile human foundation with shiny digital and physical infrastructure. China has a plausible path through its current muddle. India, by contrast, risks falling into blind alleys of unfounded optimism.

When Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi met with US President Joe Biden in the White House last month, many observers saw the makings of an evolving alliance against China. But such expectations are overwrought. As Indian Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar has made clear, a formal alliance is not in the cards, even if it is still possible to maintain long-term partnerships in a multipolar world of ‘frenemies’.

India has a long history of post-colonial mistrust of alliances. But it has also long been preoccupied with China, at least since the Himalayas border war the two countries fought in 1962. While serving in President Jimmy Carter’s administration, I was sent to India to encourage Prime Minister Morarji Desai to support a South Asian nuclear-weapons-free zone, lest the burgeoning nuclear race between India and Pakistan get out of hand. As my Indian hosts told me at the time, they wanted to be compared not to Pakistan in South Asia, but to China in East Asia.

After the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, the United States and India began 20 years of annual ‘track 2’ talks between former diplomats who were still in close contact with those in government. (The American delegation, for example, included figures such as Henry Kissinger and Richard Holbrooke.) The Indian participants shared their US counterparts’ concerns about al-Qaeda and other extremist threats in Afghanistan and Pakistan, but they also made clear that they objected to the Americans’ tendency to think about India and Pakistan as ‘linked by a hyphen’.

The Indians were also concerned about China, but they wanted to maintain the appearance of good relations—and access to the Chinese market. China has long been one of India’s largest trading partners, but its economy has grown much more rapidly than India’s. Using market exchange rates, China represented 3.6% of world GDP by the turn of this century, but India didn’t reach that level until the 2020s.

In the 2000s, as China’s growth far outpaced theirs, the Indians in the track 2 talks worried not just about China’s support for Pakistan, but also about its increasing global power more broadly. As one Indian strategist put it, ‘We have decided we dislike you less than we dislike China’—and this was long before the 2020 skirmish on the disputed Himalayan border, where 20 Indian soldiers were killed.

The India–US alignment has since strengthened considerably. A decade ago, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue meetings between US, Indian, Japanese and Australian diplomats were downplayed; now, Quad meetings are loudly publicised and held at the head-of-government level. India today holds more joint military exercises with the US than with any other country.

But this arrangement is a far cry from an alliance. India still imports over half of its arms from Russia, is a major buyer of sanctioned Russian oil (alongside China) and frequently votes against the US at the United Nations. Indeed, India has still refused to condemn Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, just as it failed to condemn the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. For all of India’s self-congratulation as the world’s largest democracy, it has not come to the defence of democratic Ukraine. Its top priorities are to maintain its access to arms and oil, and to avoid pushing Russia further into China’s embrace.

Though Biden has invited Modi to both of his Summits for Democracy, there’s no shortage of Western and Indian critics who have decried Modi’s illiberal turn towards Hindu nationalism. Recent statements about the two largest democracies’ ‘shared values’ may sound nice, but they, too, don’t make an alliance. The key to Indo-US relations is the balance of power with China, and India’s place in it.

In this respect, India’s importance is growing. Earlier this year, it surpassed China as the world’s most populous country. While India’s population has grown to 1.4 billion, China has been experiencing demographic decline, with a labour force that peaked. And India’s economy is on track to expand by 6% this year—faster than China’s—making it the world’s fifth-largest economy. If it continues at this rate, it could be the same size as the eurozone economy by mid-century.

With a huge population, nuclear weapons, a large army, a growing labour force, strong elite education, a culture of entrepreneurialism and links to a large and influential diaspora, India will remain a significant factor in the global balance of power.

But one shouldn’t get carried away. India alone can’t balance China, which got a big head start in its development. China’s economy remains about five times larger, and poverty is still widespread in India. Of India’s 900 million working-age people, only around half are in the labour force, and more than a third of women and girls are illiterate. For India’s growing population to be an economic asset, rather than a potential liability, it will have to be trained. Though China’s labour force has peaked, it rests on a higher average level of education.

Despite the selective decoupling of trade in key strategic sectors, India still doesn’t want to forgo access to the Chinese market. While it participates in the Quad, it also participates in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the periodic meetings of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). Although it no longer speaks of non-alignment, nor is it interested in restrictive alliances. Following the basic logic of balance-of-power politics, India and the US seem fated not for marriage but for a long-term partnership—one that might last only as long as both countries remain concerned about China.

No bilateral relationship has deepened and strengthened more rapidly over the past two decades than the one between the United States and India. In fact, Narendra Modi’s upcoming visit to the US will be his eighth as India’s prime minister, and his second since US President Joe Biden took office. The US has at least as much to gain from the growing closeness as India does.

India recently overtook China in population size, and although its economy remains smaller, it is growing faster. Indeed, India is now the world’s fastest-growing major economy—its GDP has already surpassed that of the United Kingdom and is on track to overtake that of Germany. India thus represents a major export market for the US, including for weapons.

But commercial opportunities are just the beginning. In an era of sharpening geopolitical competition, the US is seeking partners to help it counter the growing influence—and assertiveness—of China (and its increasingly close ally Russia). India is an obvious partner for its fellow democracies in the West, though what it really represents is a critical ‘swing state’ in the struggle to shape the future of the Indo-Pacific and the world order more broadly. The US cannot afford for it to swing towards the emerging Russia–China alliance.

Consider America’s quest to bolster supply-chain resilience through so-called friend-shoring. As Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has explained, India is among the ‘trusted trading partners’ with which the US is ‘proactively deepening economic integration’ as it attempts to diversify its trade ‘away from countries that present geopolitical and security risks’ to its supply chain.

India is also integral to maintaining peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific. Its military standoff with China—now entering its 38th month—is a case in point. By refusing to back down, India is openly challenging Chinese expansionism, while making it more difficult for China to make a move on Taiwan. Biden hasn’t commented on the confrontation, but he is certainly paying attention. It’s telling that both Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan visited New Delhi this month.

Already, India holds more military exercises with the US than any other power, and as of 2020, it had signed all four of the ‘foundational’ agreements that the US maintains with all its allies. This means that the two countries, among other things, provide reciprocal access to each other’s military facilities and share geospatial data from airborne and satellite sensors. Meanwhile, India’s involvement in the Quad—along with the US, Australia and Japan—has lent the grouping much-needed strategic heft.

Fortifying the strategic relationship with India is one of the rare issues eliciting bipartisan consensus in the US. The latest invitation to Modi to address the US Congress—he is the first Indian leader to do so twice—came from Democratic and Republican leaders alike.

Nonetheless, plenty of sceptics in the West believe that US efforts to cement strategic ties with India will disappoint. For example, one commentator recently declared that India will never be an ally of the US, and another argued that treating India as a key partner won’t help the US in its geopolitical competition with China.

A key concern is India’s commitment to retaining its strategic independence. While India has rarely mentioned non-alignment since Modi came to power, in practice, it has been multi-aligned. As it has deepened its partnerships with democratic powers, it has also maintained its traditionally close relationship with Russia.

But India’s relationships with the US and Russia seem to be moving in opposite directions. India is building a broad and multifaceted partnership with the US—covering everything from cooperation on human spaceflight to the construction of resilient semiconductor supply chains—whereas its relationship with Russia now seems limited almost exclusively to defence and energy.

Nonetheless, India isn’t prepared to shun Russia, as the West has since the invasion of Ukraine, not least because India still views Russia as a valuable counterweight to China. In India’s view, China and Russia are not natural allies at all, but natural competitors that have been forced together by US policy. A Sino-Russian strategic axis serves neither India’s nor America’s interests, yet, much to India’s frustration, the US appears to have little interest in rethinking its policy.

This isn’t the only area where India believes that US policy undermines Indian security interests. India also takes issue with America’s insistence on maintaining severe sanctions on Myanmar and Iran, while coddling Pakistan, where mass arrests, disappearances and torture have become the norm. The US is now threatening visa sanctions against officials of Bangladesh’s secular government—which is locked in a battle against Islamist forces—if it believes they are undermining elections that are due early next year.

The US is not accustomed to being challenged by its partners. Its traditional, Cold War–style alliances position the US as the ‘hub’ and its allies as the ‘spokes’. But that will never work with India. As the White House’s Asia policy tzar, Kurt Campbell, has acknowledged, ‘India has a unique strategic character’ and ‘a desire to be an independent, powerful state’. Far from a US client, India ‘will be another great power’.

Campbell is right. But that doesn’t mean that the sceptics are also right. While a traditional treaty-based alliance with India wouldn’t work, the kind of soft alliance the US is pursuing, which requires no pact but does include, as Campbell also underlined, ‘people-to-people ties’ and cooperation on ‘technology and the like’, can benefit both sides.

The US and India are united by shared strategic interests, not least in maintaining a rules-based Indo-Pacific free of coercion. As long as China remains on its current course, so will the Indo-American relationship.

Ricky Ponting, one of the most successful captains of an Australian cricket team, once described his mindset at the batting crease: ‘In my head, I don’t see the fielders. I only see the gaps.’

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Papua New Guinea last month was his second to the Pacific islands region. His last visit was in 2014, to Fiji, and while the intervening period may seem long, it’s worth recalling that no Indian prime minister had visited the region since Indira Gandhi went to Fiji in 1981, 33 years earlier.

Modi’s trip to PNG, and India’s increasing engagement with the region, show that New Delhi is beginning to see the gaps in the field. Australia may well be an effective partner for India, particularly in addressing the capacity constraints of Pacific island countries in maritime security.

India already plays a leading role in augmenting the maritime security capabilities of smaller countries in the Indian Ocean region. This includes assistance in maritime law enforcement and domain awareness, and the provision of boats and aircraft to regional partners. However, the Pacific has remained beyond the limits of India’s strategic horizons. Even with its new ‘Act East’ policy, India has been unable to stretch its resources, or to marshal its intentions in any significant manner, in the western Pacific region. Faced with serious threats along its northern land borders, and a stretched navy and coastguard, it’s unlikely that India, by itself, could be effective in strengthening the maritime security capabilities of Pacific island countries.

It was strange that maritime security didn’t feature in the action plan that emerged from the third summit of the Forum for India–Pacific Islands Cooperation in Port Moresby. There are many reasons why the issue should have been high in the agenda. Despite India’s geographical displacement from the Pacific, it’s evident that India enjoys the trust of many Pacific island countries as a natural partner in helping address their strategic concerns, particularly those related to climate change.

India is generally viewed as a viable, third alternative to the great powers, particularly to China, whose aid tends to be riddled with geopolitical traps. Moreover, India has considerable experience in tackling the types of maritime security threats that the Pacific island countries are vulnerable to. Interestingly, in 2017, India and Fiji signed an agreement to expand defence cooperation in maritime security. It is only logical to extend the same to other Pacific island countries, and to build on Australia’s experiences working in this area.

Australia has sustained a long-term commitment to supporting Pacific island countries, particularly through security cooperation that encompasses the entire spectrum from defence to human security. While there are several concurrent programs in place, India can easily join forces with Australia in three specific areas to bring greater value to these efforts.

First, India can contribute substantially to the Pacific Fusion Centre in Vanuatu, which provides strategic assessments and advisory functions to member countries in tackling security issues. India has considerable experience in developing domain-awareness solutions, including the Information Fusion Centre – Indian Ocean region. India’s expertise in maritime surveillance equipment, such as shore-based radars, automatic identification system transponders, and satellite-based surveillance systems, all of which it has provided in aid to Indian Ocean countries, would be particularly useful. India’s contribution to the Pacific Fusion Centre could also extend to improving maritime security software and other technical support.

The second facet of Pacific maritime security that India and Australia can jointly strengthen is training. The Indian Navy has a robust program for training international naval personnel through a range of basic and advanced courses for sailors and officers. Several Fijian military personnel have already trained in Indian naval establishments. India’s defence ministry could collaborate with the Australia Pacific Security College to deliver professional training modules to military and civilian personnel from Pacific island countries. India and Australia could also extend operational exposure to naval personnel from Pacific island countries by including them as observers during bilateral and multilateral exercises such as AUSINDEX and Malabar.

Third, India could substantially augment the Pacific Maritime Security Program, under which Australia provides patrol boats, associated training and maintenance support to Pacific island countries. The program has been successful in enhancing the maritime security capabilities of Pacific countries, but increasing security challenges will require that it not only be sustained, but substantially augmented. The similar support India provides to Indian Ocean island countries could well be extended to supplement Australia’s efforts and help strengthen maritime security capacity-building in the Pacific islands region.

India’s engagement with Pacific island countries would benefit from appointing a dedicated defence adviser to the region, possibly based at the high commission in Suva, Fiji. Currently, the defence adviser at the high commission in Australia performs this role. Besides assuring Pacific partners of India’s intent to engage constructively, such a move could also facilitate greater collaboration with Australia in capacity-building efforts.

One recent article highlighted the positive impact of India’s increasing involvement in the Pacific and encouraged Australia to not ‘get in the way’. If Australia and India join forces in building maritime security capabilities in the Pacific islands region, they could yield even better outcomes.

This article is part of the Australia India Institute’s defence program undertaken with the support of the Department of Defence. All views expressed in this article are those of the author only.

An Australian official once told me that Australians struggle to think beyond the American-led Anglosphere and alliance.

There might have been some hyperbole in that remark. But certainly the struggle we have in properly understanding our burgeoning relationship with India—and India as a country—suggests that official was on to something.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Sydney this week demonstrates that Australia and India are committed to one another, despite history working against us.

From the 1960s until 2014, the two countries had at best sporadic engagement.

It’s significant that Modi continued with the visit despite the cancellation of the Sydney Quad summit after US President Joe Biden was unable to travel, which then led to Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida also pulling out.

It should not be forgotten that Modi’s trusted foreign minister, S. Jaishankar, has been to Australia three times in the past year.

This demonstrates the importance that India places on Australia—in terms of the political relationship, regional strategic alignment and the large diaspora of citizens and residents with Indian heritage. The decades in which the US has been our dominant strategic partner have shaped Australia to the point that we tend to see everything through that prism.

That helps to explain the predictable reactions we have seen to Modi’s visit: in particular, looking for inconsistencies between the two countries in terms of values, with critics pointing to human rights issues and arguing that New Delhi won’t provide military support if Beijing and Washington are heading towards a conflict, say over Taiwan.

The fact that both Australia and India are democracies is a very solid foundation for a good strategic relationship. But it should not be turned into more than that. India has its own interests, as does Australia. India, especially through the diplomacy of its foreign minister, is nothing less than open about that. India is never going to be an ally in the way the US is—but it doesn’t need to be in order to be a vital partner.

It’s not a mistake to point out that Australia and India share some values but not others. It is a mistake, however, to act like we need our partners to be identical or isolate ourselves. The test is not whether a partner is a democracy without flaws.

Rather, the test for our partnership is our commitment to a common set of strategic interests in the Indo-Pacific, to be addressed by a dual-track approach, involving offering our region viable, practical options for security and prosperity while constraining the most malicious activities of Beijing across territorial encroachment, technological oppression and foreign influence.

‘We have very different histories, of course,’ Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said this week when asked about India’s relationship with Russia. ‘India has been a leader of the Non-Aligned Movement for such a long period of time. But India is a great supporter of peace and security and stability in our region.’

And in this regard India has the heft in population and influence in the region. Evidence of this can be seen in Modi’s invitation to the G7 in Japan and his visit to Papua New Guinea before coming to Australia, where he met with 14 Pacific leaders under India’s Forum for India–Pacific Islands Cooperation. Notably, PNG Prime Minister James Marape referred to Modi as ‘the leader of the global south’.

In his statement after meeting Modi on Wednesday and in his media interviews, Albanese sensibly didn’t overstate shared values—despite getting a barrage of questions in interviews about Indian democracy and New Delhi’s relationship with Moscow. Indeed, in his statement issued on Wednesday morning he mentioned neither democracy nor values.

Albanese and Modi’s meeting on Wednesday yielded mainly practical areas of cooperation: trade and investment, migration, green hydrogen, a new consulate and so forth.

But the overwhelming benefit of the partnership is that Australia doesn’t want a region dominated by one power. It wants an inclusive region, in which power is shared and aggression and coercion are deterred. And it understands that it has to work with others, including India and Southeast Asian countries.

The strength and maturity of the relationship is reflected in the fact that the two countries can discuss their individual and collective interests, which includes open discussion of the tensions in the relationship. Indeed one of the biggest changes in the past few years is that the differences can be discussed. The relationship is now that intimate and joins a short list of countries in that category for Australia, including the US, the UK and Japan.

So, where does the relationship go from here? Defence cooperation and trade are moving at a very strong pace, as is work through the Quad grouping with Japan and the US. The visit going ahead despite everything else around it being upended shows that the Australian and Indian governments are clear-eyed about what they need individually and collectively.

The challenge for Australian foreign policy is to get more creative and find a proper place for a country like India that is not politically or culturally as resonant as the US is for Australians, and is not in our immediate region, which is Southeast Asia and the Pacific—but is still a clear strategic partner in the pursuit of this vision for the region.

The video of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Papua New Guinean Prime Minister James Marape warmly embracing, followed by Marape attempting to touch Modi’s feet—a demonstration of respect in Indian culture—was a reminder that India is seen differently to many other partners in the Pacific islands.

And Marape made that clear in his comments to Modi, referring to PNG’s and India’s ‘shared … history of being colonised by colonial masters’. Marape welcomed Modi as ‘the leader of the global south’ and asked him ‘to offer a third big voice in the face of the global north’, saying that Pacific island countries ‘will rally behind your leadership at global forums’. These sentiments picked up on ideas discussed at the Voice of Global South Summit of developing countries that India had convened in January.

To some degree, the tone of Marape’s comments can be attributed to the effusive nature of the diplomatic language used during state visits. But they also highlighted that, as a fellow formerly colonised and developing country, India brings a unique perspective to its engagement in the Pacific islands region that may be appreciated by Pacific leaders. Having just concluded controversial negotiations on a defence cooperation agreement with the United States, Marape may have been especially aware of this.

Marape’s comments also echoed language used around the creation of the Non-Aligned Movement. During the Cold War, India, PNG and other—primarily developing and decolonised—countries, recognised the benefits of not formally aligning with either of the superpowers. Similar dynamics are evident today. Even without formal alignment, a country can enter into issue-based partnerships to fulfil its foreign policy goals and ambitions, or its economic development and infrastructure targets. This reflects India’s current approach—entering into the Quad with like-minded countries, for instance, but keeping its ‘strategic autonomy’ intact.

While not all Pacific leaders may share Marape’s enthusiasm for rallying behind a third voice in international affairs, the view that Pacific island countries should be ‘friends to all’ is common. Several Pacific leaders have recognised that not choosing sides in the current strategic competition empowers them to use ‘tactical, shrewd and calculating approaches’ to exploit that competition to access aid, concessional loans, military assistance and international influence. This echoes India’s approach to pursuing its interests, even when they differ from those of its partners (an example would be the ongoing Russia–Ukraine war).

While in PNG, Modi convened the third summit of the Forum for India–Pacific Islands Cooperation. He had initiated the first summit in 2014 when he travelled to Fiji, which represented a watershed in India’s outreach to the Pacific islands region. Before then, India had primarily been occupied with the Indian Ocean region and its extended neighbourhood, Southeast Asia. During the third summit in Port Moresby, Modi outlined a range of possible areas of collaboration, including suggesting that Pacific island countries join the Coalition for Disaster Resilient Infrastructure.

The different way India may be perceived in the Pacific raises questions about whether and how it will cooperate with established regional partners, such as Australia, the US, Japan, France and New Zealand.

Notably, Modi’s visit to PNG has sidelined those partners from India’s direct engagement with Pacific leaders. The Port Moresby summit excluded Australia, New Zealand and the French territories of New Caledonia and French Polynesia, even though all are members of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), the region’s premier multilateral institution.

PIF leaders, most recently in their 2050 strategy for the Blue Pacific continent, have emphasised the importance of the PIF’s centrality and regional solidarity. The exclusion of four of its members from the PNG summit raises questions about India’s commitment to those principles. Notably, when Japan holds its regular meeting with Pacific islands leaders, all 18 PIF members are invited. South Korea is holding its inaugural Korea–Pacific Islands Summit in May and is also inviting all PIF members.

India’s decision not to include all members of the PIF in the PNG summit also seems to contradict the recent Quad leaders’ joint statement, which expressed ‘respect for the leadership of regional institutions, including … the Pacific Islands Forum’. Indeed, while Australia has sought to work with India as Australia has tried to increase its presence in the Indian Ocean region, the guestlist for the PNG summit raises questions about how willing India will be to work with its Quad colleagues, and other established partners, in the Pacific islands region.

And if India does seek to work more closely with its Quad and other partners in the Pacific, it will need to reconcile this with its perceived role as a leader of the global south. Marape’s comments indicate that at least one Pacific leader welcomes India’s presence as a potential counterbalance to the increasingly polarised strategic competition between China on the one hand, and the US and its allies and partners on the other.

Yet India’s credentials as a leader of the global south with a proud history of anti-colonialism seemed to be undermined by its exclusion of New Caledonia and French Polynesia—both of which have active independence movements—from the PNG summit on the grounds that it was ‘limited to independent and sovereign nations’. That hadn’t stopped the US from inviting them to its first US–Pacific Island Country Summit in September last year.

Modi’s pledges to Pacific leaders during the PNG summit will be welcomed, particularly on shared priorities such as climate change and sustainable development. But his visit highlighted differences between India and its Quad partners in the Pacific islands region that in many ways represent a microcosm of broader challenges to their cooperation. It has also revealed contradictions in India’s role as a leader of the global south. It’s not unusual for states to adopt contradictory foreign policies, but whether they can be sustained is another issue.