Quad supports US goal to preserve rules-based order

Following the first meeting in November 2017 of the resurrected Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad, the US has been consistent in discussing the security objectives it seeks to promote through the consultations. However, US interactions with other Quad partners—including fellow democracies Australia, India and Japan—have likely convinced Washington to repackage public presentation of the dialogue proceedings and manage its expectations of what the Quad can realistically achieve.

For now, the US is probably content with simply using the Quad as a way to signal unified resolve against China’s growing assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific without directly antagonising Beijing. That may change in the future if US–China relations deteriorate further or Beijing’s behaviour towards regional neighbours becomes even more aggressive.

In today’s context of the Trump administration’s policy to keep the Indo-Pacific ‘free and open’ from coercion, Washington’s participation in the Quad makes much sense. According to both the US national security strategy and national defence strategy, China is an adversarial power seeking to ‘displace’ the US from the Indo-Pacific to ‘reorder the region in its favor’. In response, Washington has been reinvigorating its alliances and strengthening ties with its partners, not only bilaterally, but multilaterally as well, and the Quad is one such multilateral mechanism.

Washington’s key objective when contending with Beijing in the Indo-Pacific is to preserve the liberal international order that has been in place since the end of World War II. It’s no coincidence, then, that the Trump administration gravitated towards Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s ‘democratic Asian security diamond’ concept, encapsulated in an essay in 2012, as the blueprint for Quad 2.0’s activities. Abe’s security diamond concept is a values-based foreign policy approach structured around shared democratic norms, which have been highlighted in every Trump administration statement or comment on the Quad talks. (For the record, Quad 1.0 had a similar backstory under the George W. Bush administration.)

For example, after the first Quad 2.0 meeting in November 2017, the US released a statement noting that the Quad ‘rests on a foundation of shared democratic values and principles’ and that all sides pledged ‘to continue discussions to further strengthen the rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific region’. The next two Quad meetings, in June 2018 and November 2018, reiterated the same desire to preserve the rules-based order.

When asked informally about the Quad, Trump administration officials have similarly highlighted the need to bolster the rules-based order through consultations with like-minded democratic partners. While then Secretary of Defense James Mattis was attending the Shangri-La Dialogue in June 2018, he observed how ‘all four [Quad members] are democracies. That’s the first thing that jumps out at you.’ At India’s Raisina Dialogue in January 2019, the commander of US Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral Philip Davidson, characterised the Quad as a ‘burgeoning relationship rooted in some 25 years now’. He further offered that the rules-based order is important because ‘it is advocacy for free nations in terms of security, values, political systems, and the freedom to choose their own partners’.

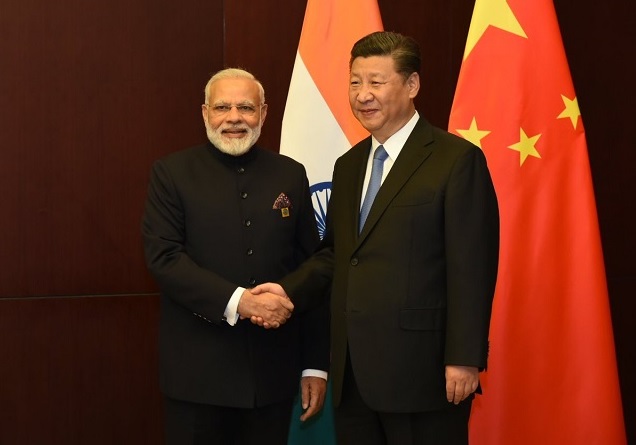

Washington’s strategy of working through the Quad to express resolve probably has its limits, as other members have shown discomfort in going too far—particularly to avoid giving the impression that the Quad is a military alliance designed to contain China. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, India likely has serious reservations. Since meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping for an informal summit at Wuhan in April 2018, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has seemingly softened his position on China to make good on their ‘reset’ in bilateral ties. During his Shangri-La Dialogue keynote speech in June 2018, Modi argued that ‘India does not see the Indo-Pacific region as a strategy or as a club of limited members’—an implicit criticism of the Quad. He also said that New Delhi prioritises regional ‘inclusiveness’ and highlighted the ‘centrality’ of ASEAN to any ordering and decision-making in the Indo-Pacific.

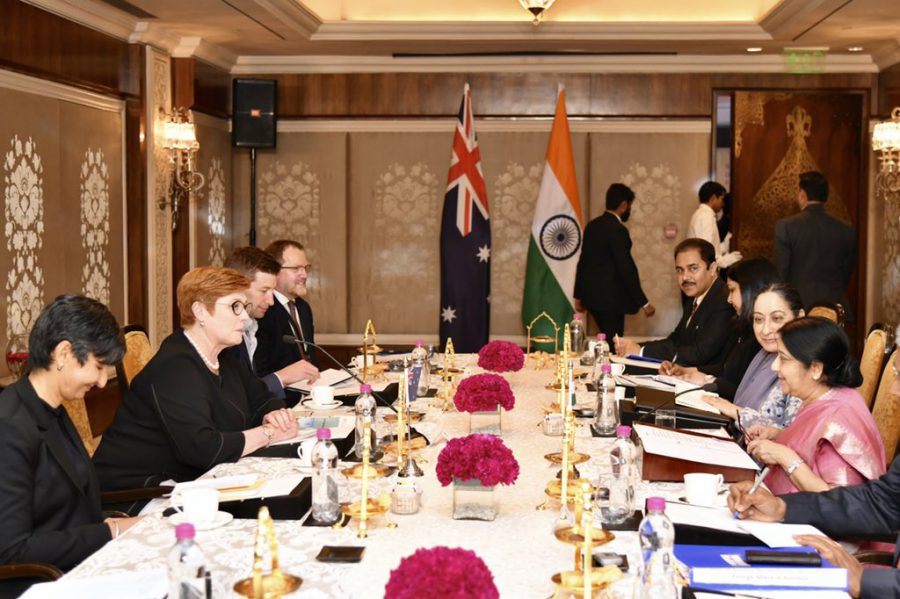

As a result, after the second Quad 2.0 meeting in June 2018, the US began including India-friendly language on the centrality of ASEAN in its Quad press statements. The shift might negatively affect Washington’s values-based approach. But, as I’ve argued previously, it’s likely to bolster the Quad’s legitimacy by bringing an ASEAN maritime counterclaimant, such as Vietnam, into the conversation to coordinate pushback against Beijing’s violation of international law and norms of behaviour in the South China Sea. New Delhi has also sought to keep the visibility of the Quad low by arguing against increasing the seniority of leadership participation to cabinet or ministry level from assistant secretary or director-general level.

India is almost certainly not the only Quad partner with concerns, judging from the fact that all four countries have yet to issue a joint communiqué. In addition, in the military domain, Quad 2.0 is yet to conduct joint military exercises or joint freedom-of-navigation operations to challenge China’s growing assertiveness in the region, which the US would likely welcome and has probably been encouraging. The first Quad iteration conducted a joint exercise in 2007 and included Singapore, so such a move wouldn’t be unprecedented. But instead of symbolic shows of force, this Quad has opted to keep a very low profile (no Quad partner has even referred to the Quad as the Quad—merely as quadrilateral ‘consultations’). In fact, US policymakers tend to describe the Quad as an example of one multilateral mechanism, among many others, that the US has at its disposal. In other words, the Quad is nothing special—unless the others collectively come to the conclusion that it is.

The US probably believes the Quad has served the basic purpose of signalling unity of resolve among democracies and like-minded partners to counter China’s growing assertiveness in the Indo-Pacific region. However, if US–China competition continues to heat up, particularly in the South China Sea, Washington will likely increasingly look to the Quad—and specifically the military dimension of the cooperation—to defend the liberal international order.