The disturbing evolution of China’s foreign policy

The international community has recently been rocked by the Hong Kong government’s chilling decision to place bounties on eight exiled activists, two of whom are currently residing in Australia. This show of transnational repression, a disturbing extension of law enforcement beyond territorial borders, is a brazen violation of human rights, personal freedoms and national sovereignty.

While it may seem like a drastic manoeuvre to silence dissidents, thereby accelerating Hong Kong’s metamorphosis into an autocratic society, this move prompts us to delve deeper into the real motives. A majority of these activists have been living in exile for two to three years. Their international advocacy against China’s restrictive policies is a matter of public record—and, more importantly, many of them had already been wanted by authorities prior to the bounty announcements. So why the sudden decision to put a price on their heads in front of the world?

The answer may lie in a critical event that transpired just two days before the bounty hunt was announced. On 1 July, the new Law on Foreign Relations of the People’s Republic of China came into effect after it was ratified by the National People’s Congress. The legislation anchors President Xi Jinping’s control over all of China’s diplomatic and national security affairs, marking a significant shift in the country’s global orientation.

The timing of these arrests suggests an attempt by the Hong Kong government to signal its unwavering alignment with Beijing. By placing a bounty on the heads of these exiled activists, the Hong Kong authorities are demonstrating that the days of foreign influence and ‘collusion’ are unequivocally over.

Hong Kong, long viewed as an Achilles’ heel by Beijing, has been a symbol of pro-democracy sentiment and the fight for universal suffrage for decades. The region’s civic tenacity was most clearly demonstrated during the anti-extradition bill protests of 2019, when around two million people took to the streets in a powerful display of civic dissent. The protests severely embarrassed Xi and the Chinese Communist Party, leading them to label the movement a ‘colour revolution’ and accelerate their efforts to repress such dissent.

Likewise, the influence of the Hong Kong activists reached well beyond their city to help reshape international relations and foreign policy during the movement. A particularly powerful achievement was the successful push for the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act in 2019 in the US Congress. The bipartisan and bicameral legislation marked a major turning point in relations between the US and China, unprecedentedly authorising the US administration to sanction Hong Kong and Chinese officials in response to the clash. That move further inspired Hong Kong activists to push for similar bills across the globe, including the ratification of a global Magnitsky-style act in Australia.

This, of course, unsettled Beijing. By transforming Hong Kong from an alleged domestic issue into a global concern, the activists have put pressure on China and forced it to deal with an international audience.

The sequence of legislation and action by Beijing should therefore not come as a surprise. With the introduction of the national security law in Hong Kong in 2020, followed by the anti-foreign sanctions law in 2021, the anti-espionage law in April 2023 and the latest foreign relations law in China, Xi’s growing intolerance for international intervention and sanctions has become increasingly apparent. These laws are both silencing the very nationals who dare to voice their dissent and building a line of defence against the West’s economic and military statecraft.

To have a closer look, Article 7 of China’s anti-espionage law vaguely but pointedly states that all citizens bear the obligation to protect the country and its national security, honour and interests. Article 8 of the new foreign relations law and Article 10 of the anti-espionage law both state that ‘anyone or any organisation that violates this law and relevant laws, and engages in activities harming national interests in foreign relations, shall be held legally responsible’. Notably, these laws don’t only target foreigners but extend to everyone residing in the country, making it clear that anyone aiding foreign actions contrary to Beijing’s interests could face severe legal consequences.

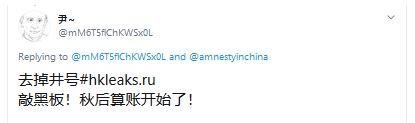

The new laws vest local authorities with sweeping powers to neutralise anyone suspected of aiding, abetting or encouraging foreign sanctions or actions deemed adversarial to Beijing and Xi. After the decision to place bounties on the activists, the Hong Kong National Security Police took away for questioning two family members of one of the wanted activists. That action also fits right into the narrative, serving as a form of relational repression aimed at isolating and intimidating dissidents—a strategy consistently adopted by the CCP in mainland China.

Coincidentally, a day after the widely publicised bounty announcement, China said that it would impose export restrictions on gallium and germanium products—critical components in computer chips—purportedly to protect national security interests. This will have an adverse impact on global supply chains and is a reminder to the world that China is gearing up to take a stand and unwilling to be passive in the face of perceived foreign hostilities and sanctions. China understands well that its biggest asymmetric advantage comes from its economic strength, surveillance capabilities and transnational repression.

In light of China’s increasing defiance, it is imperative that the international community rally behind these activists, ensuring their safety and continuing to uphold the values of freedom and democracy. Most importantly, countries such as Australia, the US and the UK should get ready for the resurgence of Chinese ‘wolf-warrior diplomacy’ and growing statecraft capabilities. As we witness a surge in China’s destabilising actions, it is essential to have coordinated and assertive responses to address this emerging global challenge.