Two speeches in three days as the world changes

Two speeches given three days apart have delivered the inspiring sense of purpose and unity the world needs as it confronts the twin empowered autocrats ruling Moscow and Beijing. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and US President Joe Biden have both risen to the demands of their time in leadership, overturning reservations many held about each before they took up their roles.

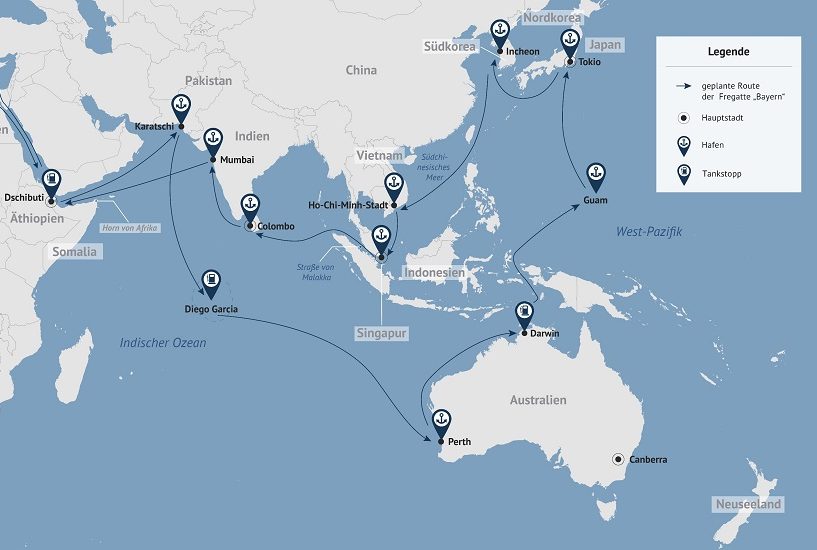

Biden is criticised by a barrage of partisan voices who seem unable to recognise even his hard-to-deny, extraordinary achievements. Right now, none is so obviously manifest and powerful as the broad international unity he has worked to create and is now driving, with partners like Germany’s Olaf Scholz, the EU’s Ursula von der Leyden, Britain’s Boris Johnson, France’s Emmanuel Macron, Japan’s Fumio Kushida, South Korea’s Moon Jae-in, Australia’s Scott Morrison and other leaders of powerful states from Oslo to Tokyo and many capitals in between.

These national leaders are joined by many others: international organisations, financial organisations (SWIFT), oil companies (BP, Shell), investors, reserve bank heads, sporting organisations (football, tennis, basketball, Formula 1 racing), civil rights groups, and even cyber hackers (Anonymous). A common feature of this messy but united international grouping is that they all understand what’s at stake in Ukraine and in dealing with Russian President Vladimir Putin and his shrinking group of international supporters and protectors.

This extraordinary coalition resisting Putin’s attempt to impose his view of world order—which he shares with his ‘no limits’ partner in Beijing, Xi Jinping—would not exist without the leadership of Biden, Scholz and von der Leyden.

Who would have predicted the steely resolve and speed of action of any of these three in the way we’ve seen in recent weeks? Maybe, in Biden’s case, those who noticed him getting trillion-dollar infrastructure spending through a divided Congress while convening the Quad leaders’ group and creating the AUKUS military technology accelerator with the UK and Australia. But certainly not Putin, his foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, or his hybrid warfare theorist and chief of the Russian general staff, Valery Gerasimov. And certainly not Xi, Minister of National Defence General Wei Fenghe and the rest of Xi’s secretive, purge-anxious advisers and acolytes.

This is not the decadent, divided West and declining democratic world that the narratives out of Beijing’s and Moscow’s propaganda machines have led some to believe. It’s not the introspective and self-doubting America Biden inherited, or the fractured and difficult set of transatlantic partnerships that characterised Donald Trump’s term, shown to the world in those surreal meetings with European leaders like Angela Merkel and Macron. And it’s not the Europe that desperately hoped to be able to ‘engage’ Putin and turn a blind eye to his growing belligerence and aggression while opening new gas pipelines to double down on dependency.

Sure, Putin can take much of the credit for galvanising and uniting this international action against him, and for forcing broken assumptions about how the world works and the policies based on them to change. In this way, he has changed the course of history and his place in it.

But the purpose, resolve, clarity and speed of action that Biden, von der Leyden and Scholz have given us in their decisions, their coalition-building and now in these two speeches is profound—steeled no doubt by the extraordinary personal courage, leadership and inspiration of Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky. Let’s manage to bring ourselves to recognise this despite prejudices, differences and partisan perspectives that may be deeply held but now are simply excess baggage to be left behind in the face of a common challenge.

In the first days of Putin’s war, von der Leyden was one of the architects of the rapidly implemented and growing international sanctions against Russia. She led the EU to act on long-debated defence issues, like an independent European defence capability and the use of EU funding to deliver urgently needed military assistance to Ukraine, and she has created momentum for Europe to shift from its dependence on Russian energy towards more diversified supply, along with an accelerated move to renewable energy. One of her insights has been to identify broader trends Europe should be working towards—like renewables—and to accelerate action on them in confronting Putin.

As we heard in his State of the Union address this week, Biden has used his domestic agenda—on innovation, jobs and infrastructure—in the same way, and America’s exit from the dark days of the pandemic is another source of energy and momentum.

The larger sense of purpose and common challenge that began with early sanctions and growing international unity has now been crystallised through Scholz’s and Biden’s words.

Scholz said on Sunday:

We are living through a watershed era. And that means that the world afterwards will no longer be the same as the world before.

The issue at the heart of this is whether power is allowed to prevail over law. Whether we permit Putin to turn the clock back to the nineteenth century and the age of great powers. Or whether we have it in us to keep warmongers like Putin in check.

That requires strength of our own. We fully intend to secure our freedom, our democracy and our prosperity.

Three days later, Biden told us:

Vladimir Putin sought to shake the foundations of the free world, thinking he could make it bend to his menacing ways. But he badly miscalculated …

Throughout our history we’ve learned this lesson: when dictators do not pay a price for their aggression they cause more chaos …

Putin’s latest attack on Ukraine was premeditated and unprovoked … He thought the West and NATO wouldn’t respond. And he thought he could divide us at home. Putin was wrong … We spent months building a coalition of other freedom-loving nations from Europe and the Americas to Asia and Africa to confront him.

When the history of this era is written, Putin’s war on Ukraine will have left Russia weaker and the rest of the world stronger.

Already, word-count analysts have said Biden’s speech contained too little about his major strategic priority—China. That’s a superficial reading. His statement that, ‘In the battle between democracy and autocracy, democracies are rising to the moment’ will be read and understood in Beijing as much as in Moscow. Similarly, the foundational elements of his speech that describe American strategy and domestic and international renewal are formed by the challenge of China, now joined with Russia through their partnership and Putin’s catalytic actions. The message Biden directed straight at Xi was chilling: ‘it is never a good bet to bet against the American people.’

Both leaders are backing their words of resolve and hope with actions. Scholz has reversed decades of concreted-in German policy on defence that constrained its power from playing a positive role in the world and investing €100 billion in new money into military capability, along with overturning the ‘untouchable’ path to growing energy dependence on Russia that he inherited from Merkel.

Biden has been absolute on America’s security commitments to every member of NATO—including Russia’s neighbours Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia and Poland—and every inch of NATO territory. Both Scholz and Biden acted on initiatives to supply Ukraine and provide humanitarian assistance to its people.

The leadership, unity-building, actions and resolve of leaders like Biden, Scholz and von der Leyden has to continue over the months and years ahead and confront more of the ugliness we must expect in the war in Ukraine and the suffering of the Ukrainian—and Russian—people inflicted by Putin.

Internationally, care will be needed to separate the confused and the cowed from those who support and sustain Putin—whether through their carefully chosen language to divide and slow international action, by helping him to subvert international sanctions or by providing him with material and financial support to sustain his war.

But for now, let’s welcome the leadership we see and bend our own will and actions in support.