Canada’s F-35: yeah but no but… yeah?

For a number of reasons, it wasn’t surprising to see Canada’s incoming government announce its intention of revisiting the former government’s decision to buy the F-35A Joint Strike fighter for the Royal Canadian Air Force. It’s not academic for Australia—if Canada decides to pull out, it could cost Australia and other partners about a million dollars extra per aircraft as economies of scale are reduced, or about A$100 million in total for the RAAF’s fleet of 72.

As in Australia, the proposed Canadian F-35 purchase has been controversial and has found itself repeatedly in the papers. Unlike in Australia, the Canadian debate has been cost rather than the capability of the aircraft. And it hasn’t been a debate in the margins: a 2011 Parliamentary Budget Officer report that highlighted the budgetary impacts of both the acquisition and through-life support costs of the F-35 led to a vote of no confidence in the House, and ultimately the dissolution of the then minority conservative government.

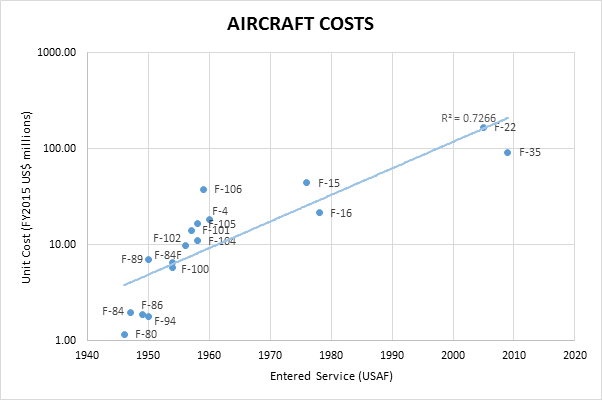

It’s no surprise that the cost of the F-35 is problematic for Canada. It’s the world’s second most expensive tactical aircraft after its F-22 stablemate. At a projected flyaway price of US$82 million in 2020, it compares to US$61 million flyaway for a new build Super Hornet (prices in 2015 dollars). Supporters of the F-35 would argue that you get a lot more capability for your money, but that doesn’t help if you’re broke. And when you look at its defence budget, Canada has been heading for the wall for a while now.

As I pointed out in a comparative analysis a few months ago, Canada’s armed forces are uncannily similar to Australia’s in size, while the defence budget is a whopping 40% smaller. Even if our northern mates are doing things smarter than we are, that’s an implausibly large amount of efficiency to find. It’s more likely that they’re expending a much greater proportion of their budget on keeping the extant forces going than we are. That’s OK until it comes time to recapitalise major assets, when you’re faced with the option of letting capabilities go or finding extra money.

Canada may have already made some tacit decisions. I’ve talked with Canadian civilian and military defence folks about the replacement of our Collins and their Upholder class submarines. The timing and requirements of the two countries actually mesh quite nicely (even if Canada extends the life of its boats it could still work), and a collaborative approach would make good sense, giving both sides some economy of scale. The response is usually an uncomfortable silence—the inference I draw being that Canada isn’t planning another generation of submarines.

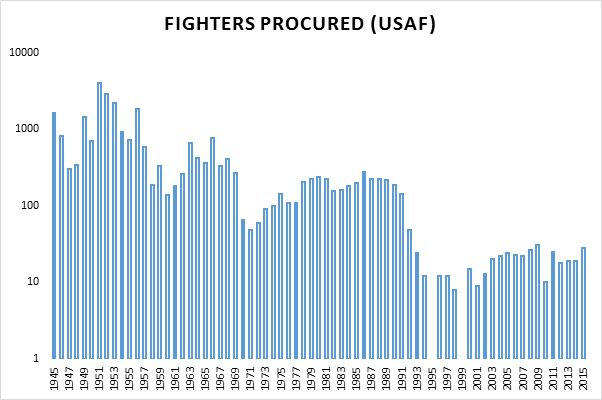

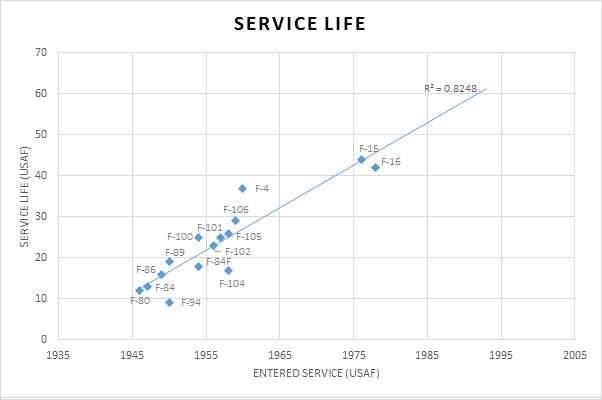

But in the F-35 case it’s far from clear what options Canada has. It could go the New Zealand path of 0% fast jet force, confident that its border with the US would let it avoid being ‘100% there for the taking‘, but that would abrogate its responsibility for northern air defence and weaken it substantially as a NATO contributor. So eventually it’s going to have to replace its 1980s vintage Hornets with something. The problem is that the something won’t cost that much less than the F-35, will offer less capability and—perhaps worst of all from a Canadian point of view—might require earlier expenditure.

The most likely alternative for Canada is the Super Hornet. European options would require new supply chains and integration of new weapons into the inventory. As Australia found, the transition from Hornet to Super Hornet is easy, with training and logistics being similar enough to significantly reduce overheads. Canada’s also attracted to the Super Hornet because of its twin engines. There was a school of thought in Australia that we need two engines to operate safely over water; the Canadian equivalent is the vast northern expanses. The argument fails to appreciate the reliability of modern American jet engines (it might make sense if you had to use Chinese engines) but it still seems to have some currency up north.

But the Super Hornet production line mightn’t be open much longer, and Canada would have to buy new aircraft now, as opposed to sometime next decade as it currently plans. It would probably pay more for the aircraft than the USN did when production was in full swing. So in net present value terms, a Super Hornet buy mightn’t be the value proposition it first appears.

The list of pros for the F-35 also includes the preference of the RCAF for the highest tech platform it can get (air forces are like that) and Canadian industry involvement in the program—always politically tough to walk away from. Canada will get some work regardless, but future opportunities for construction and support work would be highly constrained. I wouldn’t mind a small wager that Canada eventually settles on the F-35 after all.