The F-35B won’t solve Australia’s defence dilemmas

In a recent Strategist article, Malcolm Davis asked an interesting question: should Australia take a cue from Japan and deploy F-35Bs (the short take-off and vertical landing variant of the joint strike fighter) at sea?

The debate is complex. The argument against rests on the significant cost burdens associated with converting the navy’s existing landing helicopter docks to accommodate the F-35Bs or acquiring a new one (although this point has been disputed). There’s also, as Davis explains, a serious question about the survivability of large surface vessels in a war involving anti-ship ballistic and cruise missiles (a point that transcends the F-35B issue).

The argument for, on the other hand, rests on the aircraft’s potential as an enabler of a ‘system of systems’. In an operational context, that means participating in a common multi-spectrum sensor network that allows any platform to engage a target outside its line of sight, speeding up the observe–orient–decide–act loop and cementing decision superiority. That would make the aircraft a significant force multiplier for both the navy and the amphibious force it is built to deploy.

From a strategic point of view, adding a small aircraft carrier to the ADF’s capabilities would enable Australia to project force well beyond the limits of land-based aircraft. Overall, it seems the idea has traction. Davis argues that, ‘If the money is made available, a third LHD with a wing of between 12 and 16 F-35Bs, supported by a larger fleet of destroyers and frigates, is an option that should be on the agenda in any force structure debate.’

Adversary capability, however, is increasingly coming from assets that operate below a threshold of conflict that calls for deploying F-35Bs—such as ‘fishermen’ occupying maritime territory, strategically placed oil rigs, research ships mapping undersea cable routes or deploying sensor networks on the seafloor, unmanned gliders monitoring vessel movements, China Radio taking over former Australian shortwave radio frequencies, psychological and legal operations, and dual-use infrastructure established through ‘debt diplomacy’. Like anti-ship missiles, these ‘left of launch’ operations are also unfavourably shaping our strategic environment. And they cannot be countered with more of the same military capabilities they’re designed to circumvent.

Left-of-launch operations are particularly effective because they challenge the organisational architecture that any ADF asset must work within. It’s an application of architectural innovation theory, which posits that large organisations struggle to adapt when an innovation challenges their internal structures.

Xerox, for example, invented the personal computer 10 years before Apple came along, but couldn’t adapt because the PC challenged relationships between other arms of the company (photocopiers and duplicating systems). Similarly, the British Army failed to recognise the true value of the tank 100 years ago because it challenged the tactical relationship between infantry and cavalry. Left-of-launch operations ask similar questions today: if invading soldiers are a problem for the ADF, and wayward fishermen are a problem for Foreign Affairs or Home Affairs, which department solves the problem of invading fishermen?

In other words, the structure becomes the problem, internal politics abounds, and the result is strategic inertia. Davis observes that Japan should hesitate before sending its newly converted aircraft carriers into China’s anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) perimeter, which now extends ‘as far out as Guam’. Yet China was only able to extend the perimeter that far by deploying missiles onto territories it seized through left-of-launch methods. Acquiring F-35Bs won’t prevent further encroachment by similar means. The US is yet to seriously contest China’s control over those territories despite strong language and a higher tempo of freedom-of-navigation operations. That is strategic inertia. After all, if a stray oil rig off the Philippines is a problem for the State Department, and an occupying naval force is a problem for the Pentagon, which solves the problem of an occupying oil rig?

In order to overcome this inertia, the same ‘system of systems’ thinking that makes the F-35B such a potent force multiplier must equally apply to the organisational structure that governs its deployment. That means improving cooperation between the ‘systems’ of national power that exist both inside and outside traditional conceptions of Australia’s national security architecture, such as information systems (the media), commercial systems and cultural systems.

Canberra is certainly pursuing some of these avenues, as evidenced by a raft of Pacific-themed announcements and foreign visits in recent months. Yet it’s not enough to wield the Canberra-based systems of national power in isolation from those headquartered elsewhere. Like fifth-generation military platforms, all must learn to engage targets outside their individual lines of sight in order to compete in a networked world.

If the F-35B is on the agenda to improve our force-projection capabilities in the Indo-Pacific, then the agenda must also include an organisational structure that can better compete left of launch. Otherwise, the aircraft will deploy into an environment shaped by the adversary.

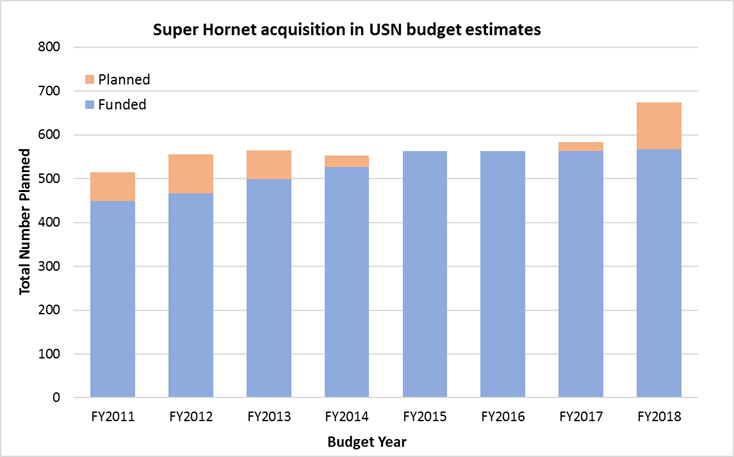

While all the signs are good for the delivery of Australia’s aircraft in the period 2018–2023, ‘never say never’ is good advice when talking about even the final stages of development of complex equipment. As we’ve argued before, the Super Hornet is Australia’s

While all the signs are good for the delivery of Australia’s aircraft in the period 2018–2023, ‘never say never’ is good advice when talking about even the final stages of development of complex equipment. As we’ve argued before, the Super Hornet is Australia’s