As antisemitism strains Australian social cohesion, the government must step forward

Australia’s national resilience and social cohesion are under strain, with the most visible cracks seen in the alarming rise of antisemitism. Governments, most particularly the federal government, whose responsibility it is to lead national debates, desperately need to engage more forthrightly with the Australian public.

The discovery in Dural of a caravan containing explosives and, reportedly, an antisemitic message and the addresses of a synagogue and other Jewish buildings, is the latest shock that will heighten anxiety in Australia’s Jewish community and further inflame public tension.

We can give police some benefit of the doubt that they had operational reasons for secrecy about the caravan, but these decisions must be balanced against the need to confront the underlying problems of extremism and hatred, and to reassure Australians that we have national leaders who are facing up to them. If our politicians had been leading the conversations that we need, there would be greater goodwill for understanding operational decisions, rather than the fraying patience that we are seeing.

Instead of confronting extremism, radicalisation and the growing influence of ideological violence, policymakers have retreated into reticence, offering platitudes that fail to give the public confidence or deter those who seek to cause harm. This absence of leadership is a communications failure and a strategic miscalculation that threatens social cohesion and national security.

The federal government’s reluctance to educate and inform the public about terrorism and extremism is fuelling uncertainty and fear. Security agencies such as the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation and the Australian Federal Police play a vital role in countering threats, but their mandate is to act once the danger has escalated to the level of criminality and national security risk.

The broader responsibility—explaining the ideological drivers of extremism, reinforcing shared values, and setting clear boundaries of acceptable conduct—belongs to the government. Yet, time and again, the government has abdicated this duty, preferring to let ASIO’s annual threat assessment stand as the only authoritative voice on extremism in Australia. That is not enough. National security is not just about neutralising threats but about preventing them from taking root in the first place.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese hardly lifted anyone’s morale when speaking defensively about the discovery of the caravan during two radio interviews on Thursday morning. On ABC radio, he failed to mention antisemitism at all. He refused to say when he’d learnt about it, describing that as ‘operational details’, and refused to say whether the national cabinet had discussed the investigation. Most of his commentary was about what the police had said and done. The closest he gave to an expression of the government’s view was by saying: ‘We remain concerned about this escalation.’

It wasn’t until a press conference later in the day that Albanese said, unprompted, that there was ‘zero tolerance in Australia for hatred and for antisemitism’ and that he wanted ‘any perpetrators to be hunted down and locked up’.

One of the core failures underpinning this crisis is a misinterpretation of tolerance. Australia prides itself on being an open and inclusive society, but inclusivity does not mean tolerating the intolerable. Support for terrorist leaders and groups is not free speech, nor is it a legitimate expression of diversity—it is a direct threat to social stability. When governments fail to call this out unequivocally, they enable a dangerous dynamic by which extremists feel emboldened, and the broader population grows resentful and anxious. An anxious public is not a resilient one.

While the rising cost of living is at the forefront of most Australians’ minds, physical and social security must remain the government’s highest priority. People need to feel safe, and that safety is reinforced not just by policing, but by clear, decisive leadership.

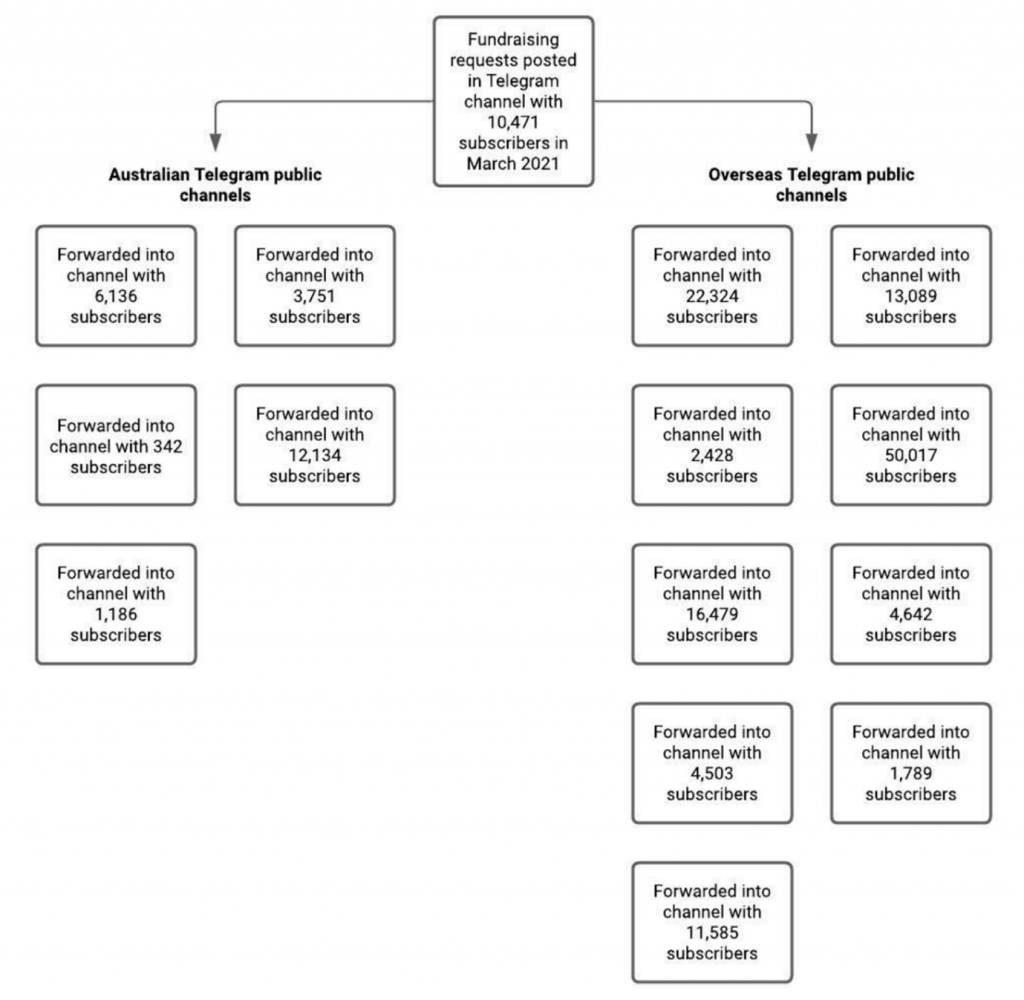

The government’s approach—avoiding public discussion for fear of inflaming tensions—belongs to a bygone era. Excessive reticence was a flawed strategy even before social media, but now, in an age in which digital communications dominate every aspect of our lives, it is a liability.

Government hesitancy leaves a vacuum that is filled by those who want society to break. Without direct and frequent public engagement, we give ground to those who distort facts, push dangerous ideologies and promote violence.

ASIO head Mike Burgess was left swinging in the breeze last September after he told the ABC that the organisation assessed entrants to Australia for any national security risk, which might not cover someone who had only expressed ‘rhetorical support’ for Hamas. Amid the political controversy that followed, the government should have swung in quickly and stressed that the wider visa check would, of course, include rhetorical support for Hamas but that this wasn’t ASIO’s job. That failed to happen, leading to days of public anger and confusion.

Equally dangerous is the government’s willingness to indulge in false equivalencies. Responding to attacks on Jewish Australians by condemning ‘all forms of hate’ or vaguely mentioning ‘antisemitism and Islamophobia’ is both politically weak and strategically harmful. Each act of violence or intimidation should be condemned for what it is—without hedging, without lumping disparate issues together, and without fear of offending those who sympathise with extremists.

This failure of clarity extends to the review of Australia’s terrorism laws, where there is discussion about removing the requirement for an ideological motive. Instead of diluting definitions, the government should lead the discussion on what ideology is, why it matters, and how it fuels extremism.

The government’s refusal to deal with reality is at the heart of this crisis. There is no neutral ground when it comes to national security. Attempting to placate all sides by responding too slowly and downplaying threats only emboldens those who seek to justify intimidation and violence.

Everyone accepts that history and geopolitics are complex—not least in the Middle East—but there is no justification for bringing foreign conflicts onto Australian streets. Like it or not, the federal government’s faltering responses have facilitated a false equivalence between Israel and Islamist terrorist groups, emboldening extremists who now see Australia as a battleground for their ideological struggles.

Australians can see the world is unstable and don’t appreciate being dismissed or misled. The government’s failure to engage honestly is backfiring. Public trust erodes when people feel their concerns are ignored, and social cohesion weakens without leadership. To maintain our national resilience, the government must step up, speak clearly and reassert the values that make Australia a safe and united society. Silence is not a strategy—it’s a surrender.