Has Putin united Europe?

A 21st-century war in Europe is no longer unthinkable. After weeks of speculation about whether Russia will invade Ukraine, a clear majority of respondents in a recent pan-European poll by the European Council on Foreign Relations think that a war is likely and that Europe should respond.

Different countries are driven by different fears, partly depending on their own recent experiences. In Poland, which has been dealing with Belarus’s attempts to funnel Middle Eastern migrants across its border, there are heightened fears of new refugee waves. In France and Sweden, cyberattacks are the primary concern, reflecting Russia’s recent interference in their national elections. And for Germans, Italians and Romanians, energy shortages are the biggest fear.

But more is at stake than Europeans’ differing perceptions of external threats. The great German strategist Carl von Clausewitz famously described war as the continuation of politics by other means, and in the early weeks of the Ukraine crisis, how countries responded to the threat of war spoke volumes about their domestic politics.

Consider the United Kingdom. Many suspect that Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s sudden interest in Eastern Europe has less to do with his concern for Ukraine than with his desire to divert attention from the revelations that his office held parties at Downing Street while the rest of the country was in lockdown. Beyond that, the crisis also may present an opportunity for him to demonstrate to the United States that post-Brexit Britain still matters.

As for US President Joe Biden, his number one goal is to minimise the resources and time needed to deal with the crisis. His mission, upon assuming office, was to deliver policies that would benefit the middle class and shift the focus of US foreign policy to the Indo-Pacific and the challenge posed by China. With former president Donald Trump threatening to return to power, it’s not just America’s policy towards Ukraine and Russia that’s at stake. So, too, is the future of American democracy.

America’s position is of great concern to Eastern and Central Europeans. They are increasingly anxious about America’s deteriorating politics and questionable resolve in the face of Russian aggression. Their biggest fear is that if Russian tanks are allowed to roll into Ukraine, their next destination could be Tallinn, Riga or even Warsaw.

Meanwhile, countries like Germany, Italy, Austria and Greece fear that a conflict over Ukraine will close off the possibility of establishing a more normal relationship with Russia. Germany is torn between its Western values, its solidarity with fellow Central and Eastern Europeans, and its postwar pacifist tradition. Hence, Chancellor Olaf Scholz has reassured other Western leaders that Germany will be a solid ally in the case of war, while also signalling that it will avoid taking a leadership role in any common European response.

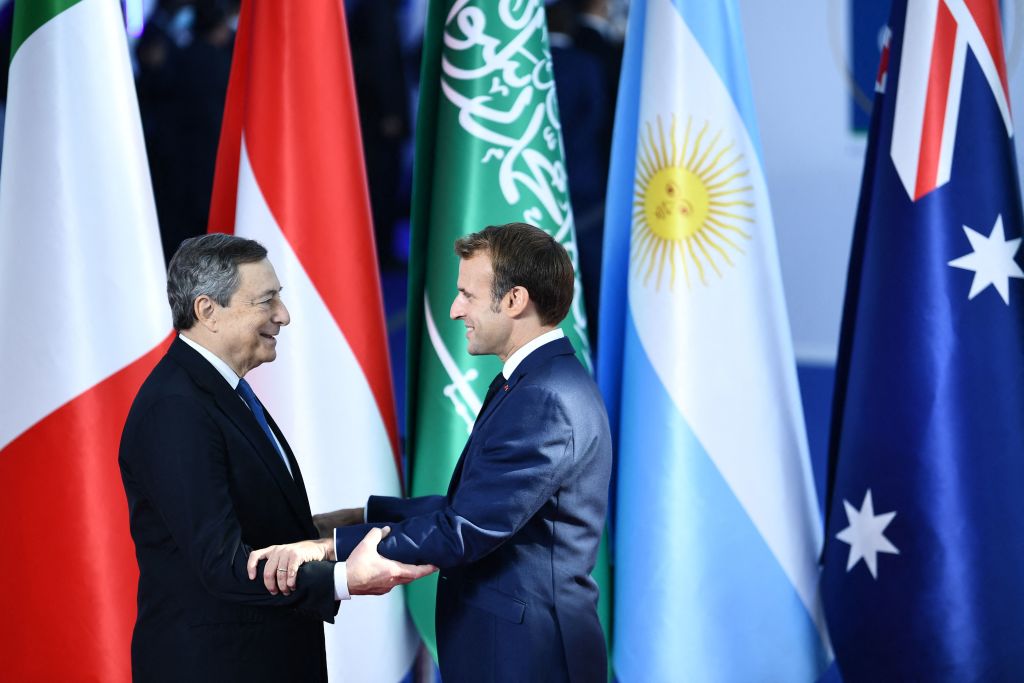

Scholz’s position stands in stark contrast to that of French President Emmanuel Macron, who sees the crisis as an opportunity to demonstrate European ‘strategic autonomy’, a policy goal that he has pursued since the start of his presidency. Of course, by assuming a visible leadership role in resolving the Ukraine crisis, Macron also can burnish his image in the run-up to France’s presidential election this spring.

With its member countries divided by geography and history, the European Union has often struggled to write itself into the story. Generally appearing passive, weak and immobile, the stereotype is that it is unwilling to either defend or revise the existing security order. Critics regard it as being paralysed by the prospect of two nightmare scenarios: an all-out war or some Yalta 2.0 scenario in which Russia and America broker a new settlement for Europe without bothering to consult Europeans.

But underlying the obvious differences are key interests that all Europeans share: the desire to prevent another war in Europe, the need to preserve NATO’s credibility and a sense of responsibility to save Ukraine from being forced back under a Russian yoke. The genius of European policymaking is its ability to reconcile domestic political imperatives with the need for international diplomacy. The European Council on Foreign Relations poll shows that, over the last few weeks, there has been a convergence among European polities about the need to respond.

At the same time, European governments are finding better ways to manage their own divisions. Though many Central and Eastern Europeans are uncomfortable about diplomatic talks, they have not sought to prevent the Americans or Macron from exploring options for engagement with Russia. And for his part, Macron has been careful to consult other countries and to stick to agreed principles concerning European security and Ukrainian sovereignty.

After initial hesitations and silence, Germany has signalled that it is willing to put all sanctions on the table. And as one EU foreign minister confided to me recently, even Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban mostly stuck to the common EU line when he met with Russian President Vladimir Putin earlier this month.

The fact that war is no longer unthinkable in Europe could force Europeans to make tricky compromises to preserve their collective peace. Though it certainly wasn’t his goal when he started massing troops on the Ukrainian border, Putin may unwittingly have helped EU member states transform themselves from a fragmented assemblage of apprehensive observers into a bloc of determined defenders of their own security.