Europe’s energy choice

Russia’s war in Ukraine and the disruption of Russian gas exports to Europe has triggered an energy crunch, with price spikes unlike anything seen since 1973. And the situation will get worse before it gets better. Russian natural-gas flows to Europe are likely to be further curtailed—or even shut off—before the northern winter, and sanctions on oil exports may soon start to bite into energy supplies, too.

The crisis is twofold. The urgency of keeping Europe warm and running through the next few winters must be considered alongside the imperative to accelerate the transition to clean energy. Many see a conflict here between the short term and the long term. But responding to the immediate energy crisis in the right way will also help to address the broader climate challenge. Authorities must both buffer the shock and accelerate the transition.

To be sure, the European countries that are most dependent on Russian gas and oil will struggle to secure power and heat for the coming winter. Gas reserves are only 65% full, and the Russian stranglehold will make it difficult and expensive to reach the European Union’s target of 80% before winter.

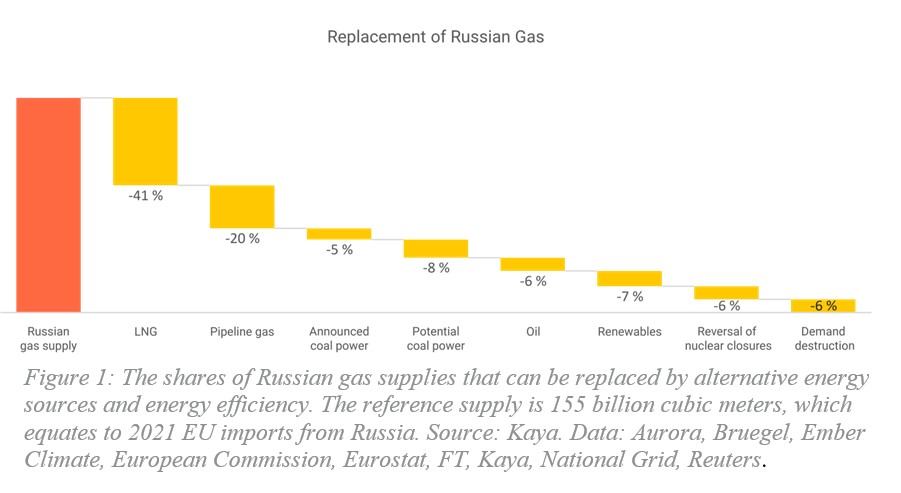

The crucial question for major economic powers, then, is whether they can manage through the winter without forcing their big domestic industrial gas consumers to shut down. The answer is probably yes, provided that Europeans demonstrate cross-border energy-savings solidarity (as suggested by the EU), and maximise the use of all other energy sources.

Letting high prices destroy marginal demand (including among private consumers) confronts policymakers with a difficult choice.

Contrary to how the situation is often framed in the media, this choice is not between climate change and civil unrest. No one doubts that Europe will need to increase its use of liquefied natural gas, continue burning coal over the next few years, and do more to help vulnerable communities and some industries manage higher energy costs. What matters is how policymakers approach these tasks.

Crucially, subsidising fossil-fuel consumption by capping energy prices at the pump or the power meter will only aggravate inflation, effectively transferring taxpayers’ money to gas and oil producers. Handing out cheques to those most in need is a good idea, whereas eliminating the incentive for everybody to save energy is a terrible one.

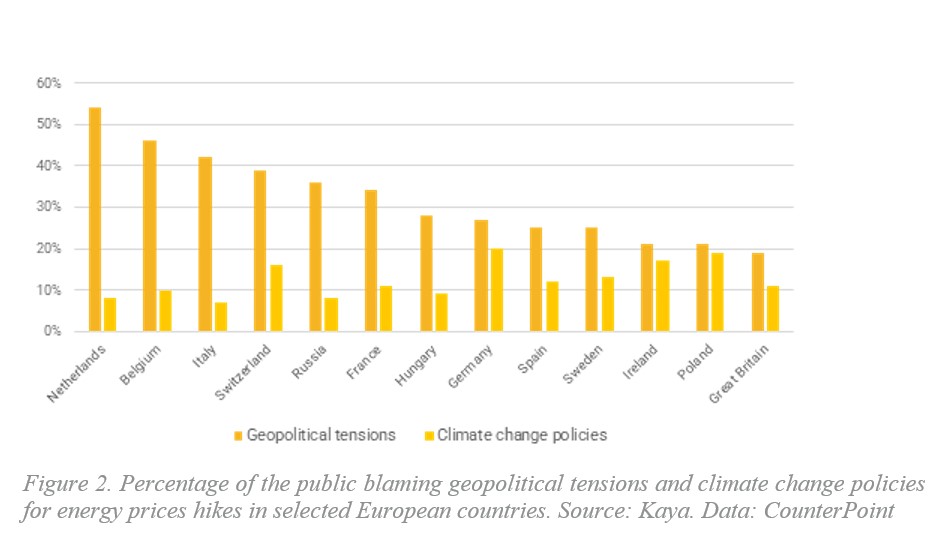

This tension is at the centre of the debates now playing out across Europe, from local municipalities to the highest decision-making levels in Brussels. While some Europeans associate today’s energy-price inflation with the war in Ukraine, others think it stems from broader efforts to combat climate change. For example, the vast majority of Italians blame the energy crunch on geopolitical tensions, whereas a significant share of Germans and Poles blame climate-change policies. Much will depend on which side wins this battle for hearts and minds.

Europe’s choice will hold important implications for whether we can limit global warming to 1.5° Celsius above pre-industrial levels. If European politicians can convince their electorates to go along with the right longer-term strategic decisions, they could both manage the energy crunch over the next few winters and leverage renewable energy and energy-efficiency improvements on an unprecedented scale.

That would position the EU decisively as one of the leading major economies in the green transition—making it competitive with China and demonstrating that wealth and welfare are not synonymous with burning fossil fuel. Conversely, if Europe panics and locks in fossil-fuel price subsidies and new investments in long-term gas infrastructure, it will have squandered a historic opportunity.

Even as we move toward a medium term in which renewables can provide stable and affordable energy, other obstacles will arise. We will need ample affordable energy, both to power everything that can be electrified and to provide zero-carbon fuels for industries, products and activities that cannot. We therefore must build the new green-energy infrastructure as quickly and cheaply as possible.

But ‘fast and cheap’ does not always align with security or dependency concerns. The new concept of ‘friend-shoring’ implies that Europe will want to source all essential parts of its energy infrastructure from allies and friendly partners as a means of ensuring reliable supplies. But while achieving near self-sufficiency through domestic green infrastructure production and friend-shoring is ultimately possible, it is not the cheapest or the fastest option in the short term.

Europe will need to engage more widely with neighbours and global partners to scale up green industries and reduce the marginal costs of green technologies. European electorates will demand fast, cheap, clean and secure energy, but satisfying them is unattainable in the short term. Once again, we are back to hard political choices. Creative political solutions can help, but politicians will have to decide on a strategy and then convince the public to come along with them. Europeans should expect nothing less of their leaders.