The EU needs fiscal union

European economic policymakers have had a packed schedule lately. First, the European Central Bank’s governing council gathered to deliberate on what would become its 10th consecutive interest-rate hike. Then, the European Union’s Economic and Financial Affairs Council met for an as-yet-inconclusive negotiation about reforms to EU fiscal rules. Finally, European ministers, central-bank governors and regulators held their traditional informal meeting to discuss economic governance and fiscal and monetary policy coordination. Unfortunately, however, none of these meetings is likely to bring the changes Europe needs.

When the Covid-19 crisis erupted, European authorities and central bankers moved quickly to implement a powerful, innovative response that few would have thought possible. But the resulting increase in public debt, together with the recent bout of inflation, has spooked policymakers. Now, some EU member states—particularly those that had reservations about the pandemic spending—are advocating a return to austerity, and the ECB has once again embraced a hawkish stance. Will this be a transient episode of reform fatigue, or is Europe poised to return to its old ways for good?

The European Commission, along with many central bankers and finance ministers, recognises that an asymmetric federation with one central bank and many fiscal authorities, each operating according to national fiscal rules, has a deflationary bias. But even though this tendency clearly puts the EU at a disadvantage compared to the United States—which can respond to crises with a far more supportive mix of policies—the political will to counter it is nowhere to be found.

The European Commission’s proposal for reforming EU fiscal rules is a case in point. Despite being less stringent than the stability and growth pact that is now in place, it includes many undesirable pro-cyclical elements. The implication is that today’s weakening growth will be accompanied by a sharp fiscal consolidation. If adopted in their current form, the proposed changes would require the EU to increase its overall structural primary surplus by an estimated 0.65% of GDP annually from 2025 to 2028. That is a significant figure—and it’s even higher in the cases of France (1.1%) and Italy (0.9%).

To achieve that level of surplus, the EU would have to undertake a coordinated fiscal tightening. And, in fact, the European Commission is already forecasting that scenario in 2024, just as the ECB has announced that monetary policy will remain in restrictive territory.

The problem, of course, is that excessive tightening under these conditions will have serious negative consequences. By 2025, at which point the ECB will probably have started its next easing cycle, one can expect monetary–fiscal crosswinds that will hamper growth and increase the likelihood of below-target inflation, as occurred in 2013–16. At the same time, the lack of fiscal space will limit public investment in critical strategic areas such as defence, energy, climate mitigation and adaptation, and technology.

Make no mistake: without some form of fiscal federalism that supports common expenditures to advance shared objectives, the EU is doomed. If the new fiscal rules are to be credible, more fiscal space must be created at the federal level. Recognising this is the first step towards breaking the EU’s longstanding political impasse (which has been reinforced by a lack of mutual trust and courageous leadership) and guiding the negotiations that follow.

On an optimistic note, the need for closer fiscal union and cohesion in tackling looming challenges is now widely recognised. However, reforms to achieve such outcomes are still viewed as tasks for the future rather than as urgent priorities. As long as the can is being kicked down the road, European fiscal and monetary policy will continue to do harm, potentially killing the patient before the cure arrives.

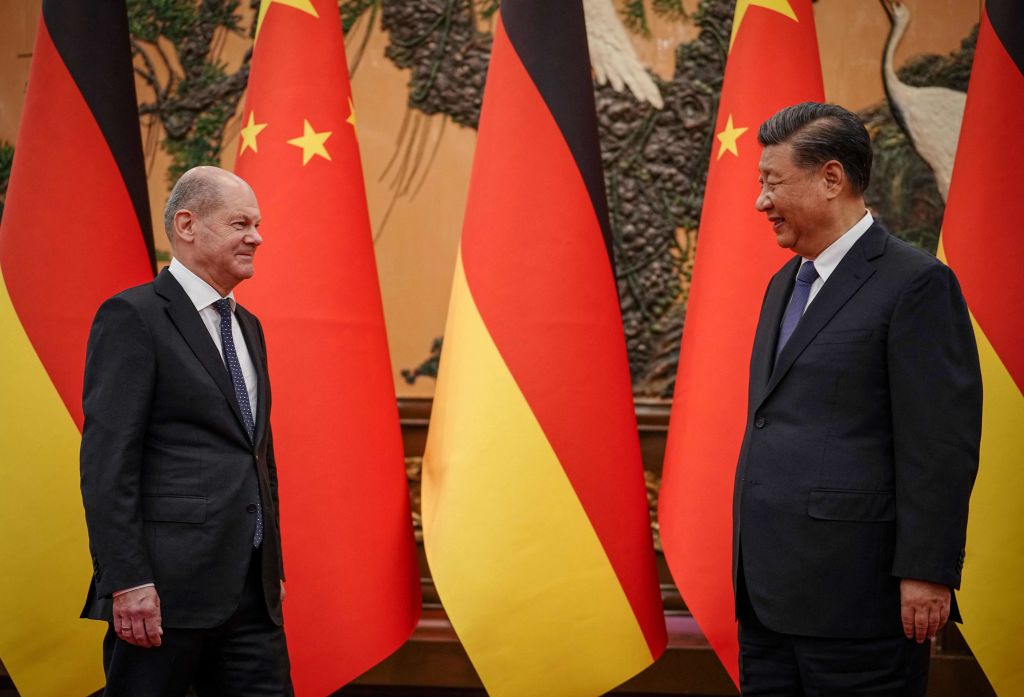

To be sure, macro policies aren’t everything, and the EU has a full plate in dealing with other urgent issues such as migration, market competition, banking regulation and the fallout from Russia’s war in Ukraine. But as long as there’s an excessive emphasis on stability over growth, Europe will remain mired in stagnation, convergence on common solutions will be difficult to achieve, and popular support for the EU will be at risk. This matters because economic integration without political support is neither desirable nor possible.

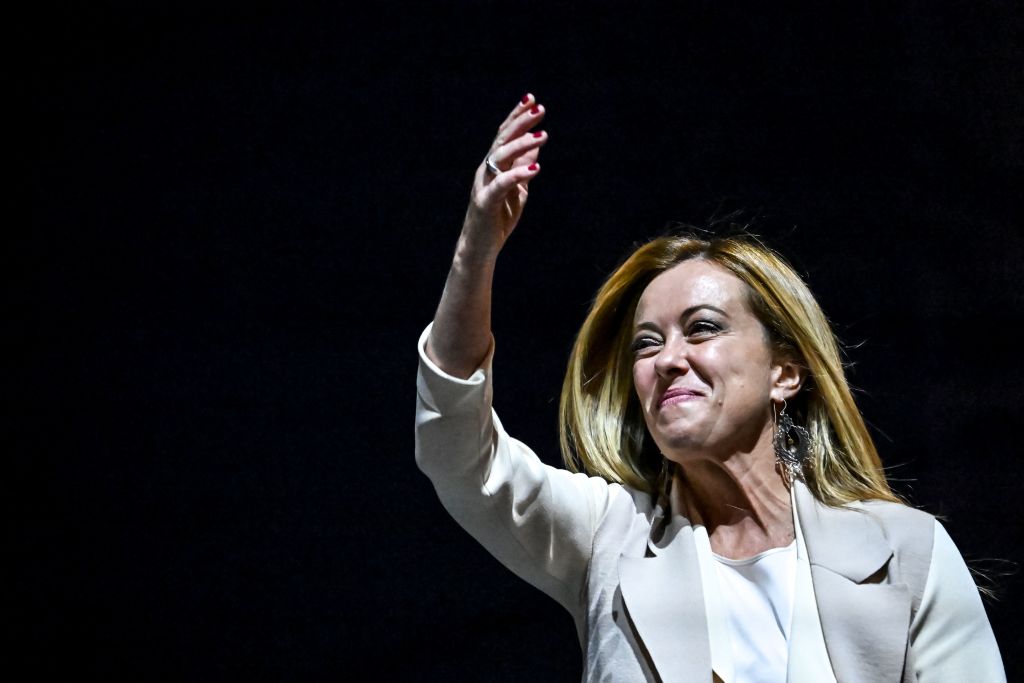

Next year’s European Parliament elections will be an important test, demonstrating the extent to which Europeans support a meaningful reform agenda and reject a return to the EU’s old ways. We can only hope that they choose wisely, and that it’s not too late.