Switzerland’s Brexit moment

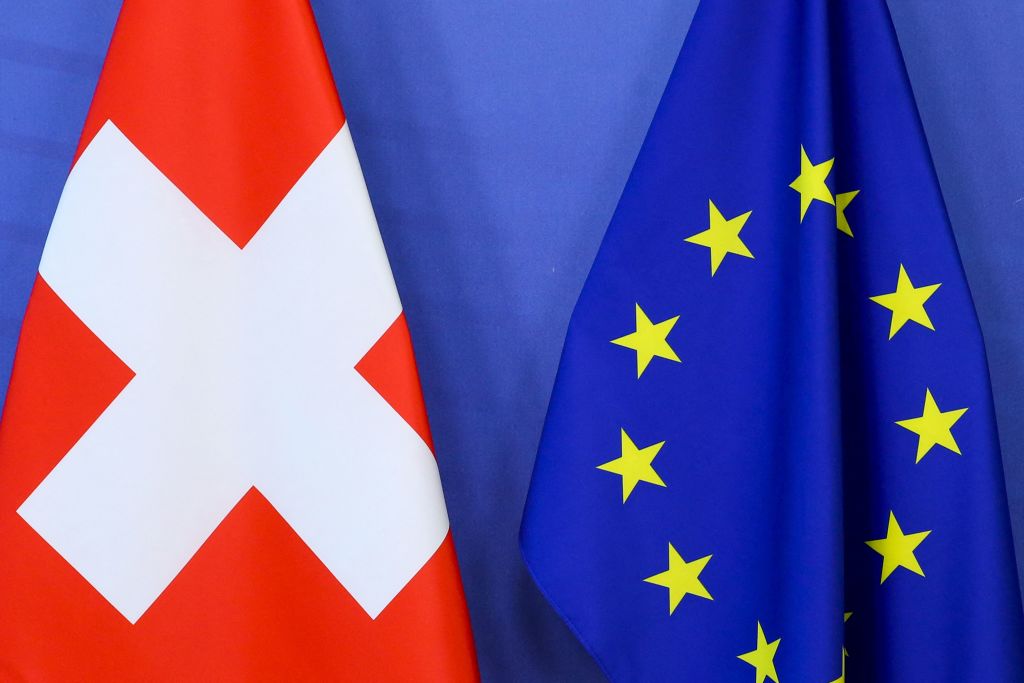

The Swiss government’s recent withdrawal from long-running negotiations on a framework agreement with the European Union has triggered a deep crisis in relations. For the EU, the fallout is manageable: economic relations will erode but the union will carry on. For Switzerland, the consequences could be more dramatic. With Switzerland’s future access to the EU’s single market in jeopardy, its walkout might now require a Swiss rethink of its relationship with the bloc almost as fundamental as the United Kingdom’s after the 2016 Brexit referendum.

Switzerland is not an EU member state, but in many respects it comes close. Through some 120 bilateral agreements, Switzerland is a member of the border-free Schengen Area, is closely integrated with the EU in areas such as transport, research and the Erasmus student-exchange program, and enjoys full access to the single market in sectors from finance to pharmaceuticals.

All told, Switzerland probably benefits more from the single market than any other European country—and pays little in return. A 2019 Bertelsmann Stiftung study found that the single market boosts Swiss annual per capita income by €2,900 ($4,576) per year—well above the EU average of €1,000 ($1,578) —whereas Switzerland’s corresponding financial contribution (when it is paid) in effect cost the Swiss less than €14 ($22) per capita per year.

Switzerland’s free lunch is not only economic. The main problem with the ‘bilateral way’, cherished by the Swiss since they voted ‘no’ to the European Economic Area (EEA) in a 1992 referendum, is the lack of continuous updating of single-market law in Switzerland. Swiss public opinion has long held that ‘foreign judges’ should have no role in interpreting the country’s laws. Yet, this clashes with the single market’s requirement of uniform application of supranational rules.

The Institutional Framework Agreement (IFA) that the EU and Switzerland reached in 2018, after five years of negotiations, was a belated attempt to put bilateral relations on a sustainable footing and pave the way for further Swiss access to the EU market. To secure it, the EU again made significant concessions in the face of Swiss sovereignty concerns.

Rather than requiring automatic incorporation of single-market law, the EU allowed for three years of internal Swiss procedures to adopt it (including possible referendums). And instead of insisting on sole jurisdiction for the Court of Justice of the European Union, the EU agreed to an arbitration-based dispute-settlement mechanism that would seek the CJEU’s intervention only for interpreting concepts of EU law.

Significantly, the EU also conceded that the IFA would cover only five market-access agreements, from transport to free movement of persons. The 1972 bilateral free trade agreement remained off-limits, with the two sides issuing only a statement of political commitment to its future modernisation.

But despite these concessions—which would place at risk the single market’s level playing field—the Swiss government never signed the IFA, or even defended it. On the contrary, the Swiss strategy was always to come back for more—until they walked away.

The talks had been made difficult because of disagreements over state-aid rules. Under the IFA, the EU offered a two-pillar arrangement whereby the EU rules would apply in Switzerland but would be implemented through an autonomous Swiss surveillance mechanism with powers equivalent to the European Commission’s. But when the EU negotiated its post-Brexit relationship with the UK, some in Switzerland thought that the UK received a ‘better’ state aid deal.

This ‘Brexit envy‘ is entirely unjustified. Whereas Brexit involved the UK’s complete departure from the single market, the entire purpose of the IFA was for Switzerland to remain within it.

The even bigger thorn in the EU’s side has been Switzerland’s remonstrations against the bloc’s citizens’ freedom-of-movement rights to Swiss social security benefits, and its concerns about downward pressure on domestic wage levels. Here too, the Swiss have a weak case.

Following the Swiss 2014 referendum ‘against mass immigration’, the EU conceded that Swiss law could require Swiss employers to give priority to domestic job seekers. The IFA grants exceptions—provided these are non-discriminatory and proportionate—to protect Swiss wage levels. And the CJEU has recognised that freedom of movement is not absolute and that economically inactive EU citizens may be excluded from other member states’ social benefits.

The EU could not concede more. Precisely because these tricky issues are not unique to Switzerland, the EU cannot give the Swiss a free pass. Treating all countries alike matters not only for the integrity of the single market, but also for the EU’s political viability. If the EU were to give non-members privileges that even members don’t have, more might head for the exit. The EU and Switzerland must find solutions within a common framework of rules, not outside them.

Many in Switzerland fail to recognise their exorbitant privileges vis-à-vis the EU, and that this cherry-picking cannot continue after Brexit. The Swiss government has shown little interest in a fair single-market settlement with the EU and, having broken off talks, now faces some immediate economic consequences.

For starters, future single-market access in electricity and health is off the table. And on 26 May, Switzerland lost access to the EU market for new medical devices, because the EU–Switzerland mutual recognition agreement was not updated. Machinery and chemicals are next in line. Bit by bit, the two economies will decouple in these sectors, at an estimated cost to Switzerland of up to €1.2 billion ($1.9 billion) per year.

The EU must soon make other hard choices, not least concerning Switzerland’s participation in the bloc’s Horizon Europe research program. Research cooperation is obviously mutually beneficial. But with the Swiss holding up their financial contributions and spurning efforts to find viable institutional solutions, the EU seemingly has little choice but to put its foot down.

The EU–Switzerland rupture comes as the UK government also is brazenly confronting the union by stepping away from key provisions of the Ireland – Northern Ireland protocol and asking the EU to adapt. With Norwegian support for the EEA increasingly unstable, several of the EU’s wider economic partnerships are in play.

But it’s the Swiss who face the most difficult choices. A recent opinion poll showed that more than 60% of Swiss are in favour of the IFA. But similar majorities support the EEA model, or even the model of EU–UK and EU–Canada agreements.

As the commission reminded the Swiss government after it broke off the talks, the bilateral relationship urgently needs modernising. Instead, it’s entering the unknown.