Trump could make Asia more united

US President Donald Trump has raised the spectre of economic and geopolitical turmoil in Asia. While individual countries have few options for pushing back against Trump’s transactional diplomacy, protectionist trade policies and erratic decision-making, a unified region has a fighting chance.

The challenges are formidable. Trump’s crude, bullying approach to long-term allies is casting serious doubt on the viability of the United States’ decades-old security commitments, on which many Asian countries depend. Worse, the US’s treaty allies (Japan, South Korea and the Philippines) and its strategic partner (Taiwan) fear that Trump could actively undermine their security, such as by offering concessions to China or North Korea.

Meanwhile, Trump’s aggressive efforts to reshape the global trading system, including by pressuring foreign firms to move their manufacturing to the US, have disrupted world markets and generated considerable policy uncertainty. This threatens to undermine growth and financial stability in Asian economies, particularly those running large trade surpluses with the US—such as China, India, Japan, South Korea and countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Currency depreciation may offset some of the tariffs’ impact. But if the Trump administration follows through with its apparent plans to weaken the US dollar, surplus countries will lose even this partial respite, and their trade balances will deteriorate. While some might be tempted to implement retaliatory tariffs, this would only compound the harm to their export-driven industries.

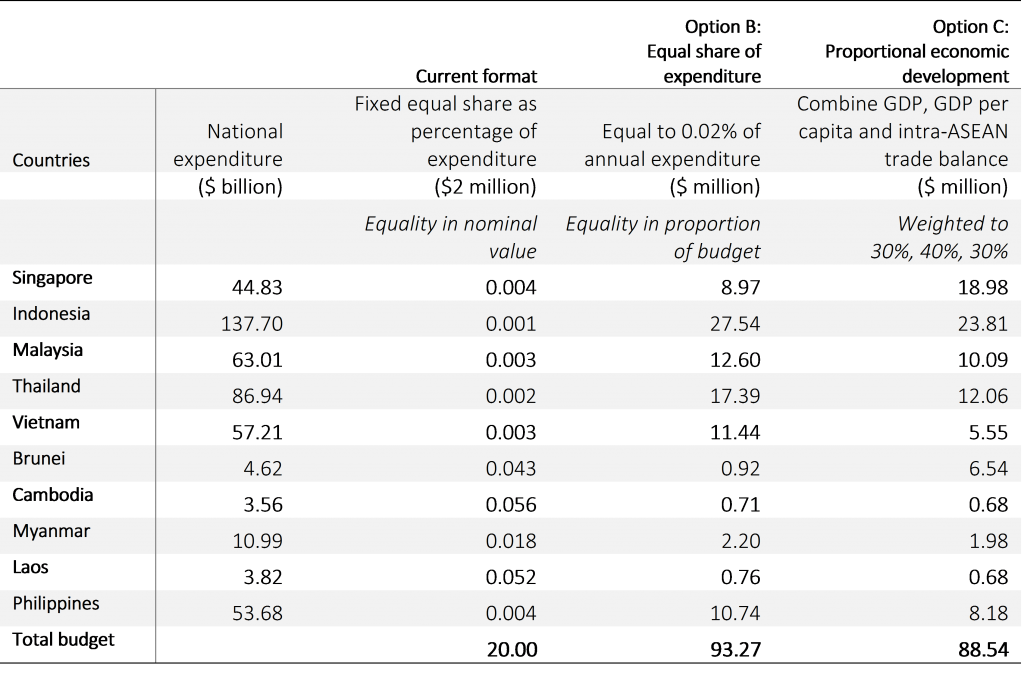

Acting individually, Asian countries have limited leverage not only in trade negotiations with the US, but also in broader economic or diplomatic disputes. But by strengthening strategic and security cooperation—using platforms such as ASEAN, ASEAN+3 (with China, Japan and South Korea), and the East Asia Summit—they can build a buffer against US policy uncertainty and rising geopolitical tensions. And by deepening trade and financial integration, they can reduce their dependence on the US market and improve their economies’ resilience.

One priority should be to diversify trade partnerships through multilateral free-trade agreements. This means, for starters, strengthening the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership—which includes Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Britain and Vietnam—such as by expanding its ranks. China and South Korea have expressed interest in joining.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership—comprising the 10 ASEAN economies, plus Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea—should also be enhanced, through stronger trade and investment rules and, potentially, the addition of India. Given the Asia-Pacific’s tremendous economic dynamism, more robust regional trade arrangements could serve as a powerful counterbalance to US protectionism.

Asia has other options to bolster intra-regional trade. China, Japan and South Korea should resume negotiations for their own free-trade agreement. Japan and South Korea are a natural fit, given their geographic proximity and shared democratic values. The inclusion of China raises some challenges—owing not least to its increasingly aggressive military posture in the region— but they are worth confronting, given China’s massive market and advanced technological capabilities. With the US putting economic self-interest ahead of democratic principles, Asian countries cannot afford to eschew pragmatism for ideology.

Beyond trade, Asia must build on the cooperation that began after the 2008 global financial crisis. The Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation, which provides liquidity support to its member countries (the ASEAN+3) during crises, should be strengthened. Moreover, Asian central banks and finance ministries should work together to build more effective financial-stability frameworks—robust crisis-management arrangements, coordinated policy responses and clear communication—to stabilise currency markets and financial systems during episodes of external volatility.

Trump is not the only reason why Asia should deepen cooperation. The escalating trade and technology war between the US and China is threatening to divide the world into rival economic blocs, which would severely disrupt global trade and investment. But there is still time to avoid this outcome, by building a multipolar system comprising multiple economic blocs with overlapping memberships. By fostering economic integration, within the region and beyond, Asian countries would be laying the groundwork for such an order.

In an age of geoeconomic fragmentation, Asian countries could easily fall victim to the whims of great powers. But by strengthening trade partnerships, reinforcing financial cooperation, enhancing strategic collaboration and building economic resilience, they can take control over their futures and position Asia as a leading architect of a reconfigured global economy.