Donald Trump and the Kindleberger trap

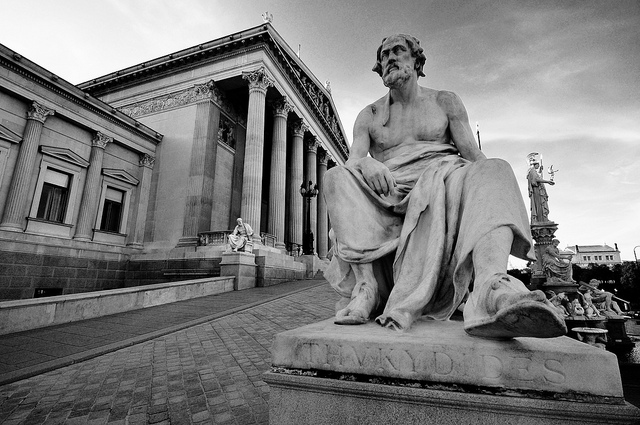

As US President-elect Donald Trump prepares his administration’s policy toward China, he should be wary of two major traps that history has set for him. The ‘Thucydides Trap,’ cited by Chinese President Xi Jinping, refers to the warning by the ancient Greek historian that cataclysmic war can erupt if an established power (like the United States) becomes too fearful of a rising power (like China). But Trump also has to worry about the ‘Kindleberger Trap’: a China that seems too weak rather than too strong.

Charles Kindleberger, an intellectual architect of the Marshall Plan who later taught at MIT, argued that the disastrous decade of the 1930s was caused when the US replaced Britain as the largest global power but failed to take on Britain’s role in providing global public goods. The result was the collapse of the global system into depression, genocide, and world war. Today, as China’s power grows, will it help provide global public goods?

In domestic politics, governments produce public goods such as policing or a clean environment, from which all citizens can benefit and none are excluded. At the global level, public goods—such as a stable climate, financial stability, or freedom of the seas—are provided by coalitions led by the largest powers.

Small countries have little incentive to pay for such global public goods. Because their small contributions make little difference to whether they benefit or not, it is rational for them to ride for free. But the largest powers can see the effect and feel the benefit of their contributions. So it is rational for the largest countries to lead. When they do not, global public goods are under-produced. When Britain became too weak to play that role after World War I, an isolationist US continued to be a free rider, with disastrous results.

Some observers worry that as China’s power grows, it will free ride rather than contribute to an international order that it did not create. So far, the record is mixed. China benefits from the United Nations system, where it has a veto in the Security Council. It is now the second-largest funder of UN peacekeeping forces, and it participated in UN programs related to Ebola and climate change.

China has also benefited greatly from multilateral economic institutions like the World Trade Organization, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. In 2015, China launched the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, which some saw as an alternative to the World Bank; but the new institution adheres to international rules and cooperates with the World Bank.

On the other hand, China’s rejection of a Permanent Court of Arbitration judgment last year against its territorial claims in the South China Sea raises troublesome questions. Thus far, however, Chinese behavior has sought not to overthrow the liberal world order from which it benefits, but to increase its influence within it. If pressed and isolated by Trump’s policy, however, will China become a disruptive free rider that pushes the world into a Kindleberger Trap?

Trump must also worry about the better-known Thucydides Trap: a China that seems too strong rather than too weak. There is nothing inevitable about this trap, and its effects are often exaggerated. For example, the political scientist Graham Allison has argued that in 12 of 16 cases since 1500 when an established power has confronted a rising power, the result has been a major war.

But these numbers are not accurate, because it is not clear what constitutes a “case.” For example, Britain was the dominant world power in the mid-nineteenth century, but it let Prussia create a powerful new German empire in the heart of the European continent. Of course, Britain did fight Germany a half-century later, in 1914, but should that be counted as one case or two?

World War I was not simply a case of an established Britain responding to a rising Germany. In addition to the rise of Germany, WWI was caused by the fear in Germany of Russia’s growing power, the fear of rising Slavic nationalism in a declining Austria-Hungary, as well as myriad other factors that differed from ancient Greece.

As for current analogies, today’s power gap between the US and China is much greater than that between Germany and Britain in 1914. Metaphors can be useful as general precautions, but they become dangerous when they convey a sense of historical inexorableness.

Even the classical Greek case is not as straightforward as Thucydides made it seem. He claimed that the cause of the second Peloponnesian War was the growth of the power of Athens and the fear it caused in Sparta. But the Yale historian Donald Kagan has shown that Athenian power was in fact not growing. Before the war broke out in 431 BC, the balance of power had begun to stabilise. Athenian policy mistakes made the Spartans think that war might be worth the risk.

Athens’ growth caused the first Peloponnesian War earlier in the century, but then a Thirty-Year Truce doused the fire. Kagan argues that to start the second, disastrous war, a spark needed to land on one of the rare bits of kindling that had not been thoroughly drenched and then continually and vigorously fanned by poor policy choices. In other words, the war was caused not by impersonal forces, but by bad decisions in difficult circumstances.

That is the danger that Trump confronts with China today. He must worry about a China that is simultaneously too weak and too strong. To achieve his objectives, he must avoid the Kindleberger trap as well as the Thucydides trap. But, above all, he must avoid the miscalculations, misperceptions, and rash judgments that plague human history.