Australia’s disaster response should build resilience

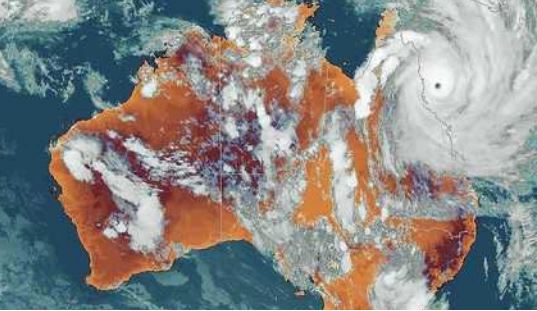

When ASPI’s Cyclone Tracy: 50 Years On was published last year, it wasn’t just a historical reflection; it was a warning. Just months later, we are already watching history repeat itself.

We need to bake resilience into infrastructure, supply chains and communities, ensuring they are prepared for the next disaster, not just rebuilt to fail again.

This requires: a long-term effort to disaster-proof communities; cross-industry collaboration to strengthen supply chains; and a national resilience strategy.

In 1974, Cyclone Tracy forced Australia to rethink disaster preparedness. But in the five decades since, we’ve seen flood after cyclone after fire.

The February 2025 floods across northern Queensland—from Cairns to Townsville—once again exposed the region’s vulnerabilities.

Communities in Ingham and Cardwell faced widespread devastation. For two weeks, road networks were severed, triggering food shortages and economic disruption. In Cairns, homes that had only just been repaired after Cyclone Jasper were inundated again, highlighting the compounding effect of disasters. Townsville, while spared the catastrophic flooding seen in 2019, remains at risk and may not be as fortunate next time.

In response, the federal government has committed $84 million to strengthen disaster resilience in northern Queensland—a necessary but vastly insufficient sum.

The cost of inaction is rising rapidly, not only in infrastructure damage but in the long-term economic and social stability of the region.

The weaknesses seen during the February floods were not new. Essential supply chains were crippled as roads disappeared under floodwaters. The housing crisis worsened as displaced families were left scrambling for shelter in an already overstretched market. Small businesses, the backbone of regional economies, were once again left picking up the pieces.

And yet, the response remains the same: mop up, rebuild, repeat.

Communities need immediate disaster relief. But real resilience isn’t about recovery—it’s about making sure the same destruction doesn’t happen again.

That means disaster-proofing communities by:

—Retrofitting homes in high-risk areas with stronger materials and flood-resistant designs;

—Updating building codes for future-proofed development;

—Reinstating and expanding the Resilient Homes Fund to cover cyclone- and flood-prone regions;

—Reviewing the insurance system so unaffordable premiums don’t leave people uninsured; and

—Investing in community-led preparedness, building resilience with local knowledge and digital tools.

While much of the focus remains on housing and road repairs, supply chain resilience continues to be overlooked. When floods cut off road transport, food shortages quickly followed. The conversation remained reactive, surfacing only after supply lines had already collapsed. There was no plan to use alternative routes.

Collaboration across industries can strengthen supply chains and critical infrastructure. It should include review processes after disasters.

Australia’s national logistics framework must embed resilience into infrastructure planning. Maritime transport, for example, could have played a much stronger role in maintaining essential goods distribution. But without a contingency plan, there was no mechanism to pivot away from road transport.

Australia needs a national resilience strategy to consider ways to bolster northern infrastructure, supply chains and communities.

The strategy should consider alternative freight corridors to reduce reliance on flood-prone roads. This could include pre-established plans for emergency supply distribution via maritime transport and would require strengthening port infrastructure.

Beyond supply chains, emergency infrastructure must also be adaptable. For example, the temporary single-lane bridge built by the Australian Army over Ollera Creek restored access between Townsville and Ingham, but was unsuitable for heavy vehicles.

A national resilience strategy should also consider strategically positioning maritime assets. Historically, HMAS Cairns has supported various naval vessels, including landing craft. Given the region’s vulnerability to cyclones and flooding, relocating both light and heavy landing craft to Cairns would enable faster disaster response across the region. HMAS Cairns is already well-equipped to support and service these vessels.

This isn’t just a northern Queensland problem; it’s a national crisis. The Colvin Review found that 87 percent of Commonwealth disaster funding is spent on recovery, while the economic cost of disasters is projected to reach $40.3 billion annually by FY2050. The Insurance Council of Australia advised that redirecting funds from the 9 percent stamp duty on insurance premiums to resilience measures could save $6.3 billion by 2050. Yet, funding remains locked in a reactive cycle—fixing damage rather than preventing it.

As we head into a federal election, there’s a risk that disaster resilience becomes just another political football—but it shouldn’t be. The escalating costs of disasters affect all Australians, regardless of who is in power.

Fifty years ago, Cyclone Tracy forced Australia to rethink how it built cities, leading to sweeping reforms in building codes and urban planning. Queensland Premier David Crisafulli has repeatedly stated a commitment to ‘building back better’. It’s time to turn those words into action.