Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

For over 15 years now, there’s been an ASPI presentation on the defence budget at the Australian Defence Magazine’s annual defence industry conference. Mark Thomson did the lion’s share of them, but I’ve been the bunny in the headlights for the last couple of them—including this year’s. Mark retired from ASPI a couple of weeks ago, and I’m on a countdown to next month, so today’s appearance was in many ways a valedictory defence industry talk.

It’s an interesting time to be reflecting on the defence budget and the state of Australia’s defence industry policy settings. To paraphrase the prime minister, there’s never been a more exciting time to be in local defence industry. In stark distinction to the disappointments that followed the 2009 defence white paper (and the only marginal improvement after the 2013 white paper), the past two federal budgets have fully delivered on the fiscal promises of the 2016 paper. While the big ramp up of investment in new equipment is just getting underway, defence got a 6.5% real budget increase this financial year. Australian wage earners should be so lucky.

For those who care (and you really shouldn’t), the defence budget this year is 1.9% of GDP. On current projections of the defence budget and GDP growth, it will hit the ‘magic’ figure of 2% sometime around 2020. Nothing significant will happen when it does.

The mid-year economic and fiscal outlook (MYEFO, PDF) was fairly neutral for the defence budget, just bringing forward a little money from the last two years of the forward estimates into the next couple of years. (Note that ‘little’ is relative here—it amounts to a billion dollars.) The broader economic outlook in the MYEFO contained a slight downgrading of projected GDP growth for this year (from 2.75% to 2.5%) but predicts 3% growth in the three subsequent years. Recent history suggests that those projections will prove to be slightly optimistic, and we can never rule out a major shock in the world economy—that’s really what cruelled the 2009 defence white paper, which was prepared before the full impact of the GFC was apparent. But failing a major downturn, the money will be there for defence if government priorities don’t shift.

The one danger lurking in the wings for defence is actually good news on the economic front: the budget deficit is shrinking, and doing so faster than previously predicted. The MYEFO projects a deficit of $23.6 billion this year (down from $29.4 billion at budget time) and $20.5 billion next year. And it might be still better than that, as recent Department of Finance data shows. Mark Thomson has written extensively about the tendency for governments to grab money back from the budget to reach surplus a year earlier if the difference is small enough. The most egregious cases—at least as far as defence is concerned—were the Swan/Gillard budgets, when a narrow surplus seemed possible (how innocent we all were back then), but there are precedents from both sides of politics. With an election set for 2019, the narrowing of the deficit might portend some ‘borrowing’ from the outer years.

Not that all of the challenges facing Defence are from the government’s control of the purse strings. If all the money gets delivered, Defence has to be able to spend it. And there’ll be a lot to spend. Five years ago, the defence capital investment program amounted to $5.7 billion and represented just 22.4% of the overall budget. This year it is $11.6 billion and 33.4% of the pie. By the middle of the next decade it will be $19.2 billion (in this year’s money)—fully 40% of a substantially larger budget.

In my ADM talk last year I fretted about the implausibility of getting enough project approvals through the National Security Committee of the cabinet to keep the white paper program on track. It seemed like a very big ask. The average number of approvals (both first and second pass) over the preceding 15 years (i.e. after the Kinnaird reforms) was 22, while at least 44 were required in 2016–17 to keep on track. Even the biggest years saw just 27 approvals. I couldn’t see how it was all going to work.

I was wrong. The 2016–17 Defence annual report cites no fewer than 15 first pass, 31 second pass and 15 ‘other types of IIP project approvals’. I wish I could tell you how they did it—and how robust those numbers are—but there simply isn’t enough information in the public domain to tell. For reasons best known to itself, the government has decided that it will be highly selective in the approvals it announces.

Nonetheless, that’s good news, right? I wish I could be so sure. Of the approvals that have been announced, several of them have big unanswered questions about project fundamentals. Mark Thomson and I wrote about some of them late last year, and nothing I’ve heard since has made me any more confident that the technical specifications and industrial arrangements have been sorted.

That matters. There’s abundant data that shows the bad outcomes that ensue from rushing into complex projects. (See my earlier piece here and the GAO report linked to therein.) And that was, of course, the rationale for the Kinnaird two-pass process in the first place—to spend time and money before final approval to reduce risk and improve project outcomes. As near as I can tell, the Kinnaird reforms had a positive impact on project cost and schedule estimates (with the effect most noticeable on costs), but effectively acted to slow down the number of approvals by requiring more upfront effort.

So the sudden flurry of approvals, accompanied by apparent confusion in some big projects, makes me think that everything old is new again. It’s possible that the can has just been kicked down the road and that rapid approvals today will be tomorrow’s projects of concerns. Time will tell.

In my last post, I considered the high-level strategic policy implications of strengthening Australia’s relationships with the US and other nations as part of an effort to support the US national defence strategy (NDS). That will require greater coordination between Australia, the US and our Asian partners on capability development.

One contribution we could make immediately is to acquire the ability to carry out long-range strikes, thus filling a gap in the ADF’s force structure as envisaged in the 2016 defence white paper and the integrated investment program (IIP). As I’ve explored previously, that could involve installing naval land-attack cruise-missile systems on submarines and naval surface combatants. Or, in the longer term, we could acquire common long-range bomber systems alongside the US. That would demand careful diplomatic coordination in the region to avoid misperceptions and reassure our partners about why we’re acquiring such a capability. We’d need to make it clear that the overall objective would be to counter China’s advantages in anti-access and area denial (A2AD) operations.

Achieving that outcome is not going to be a quick process. There’s no technological ‘easy fix’, and Chinese efforts to enhance A2AD with new weapons will certainly accelerate. The NDS provides some broad guidance, though no specifics, on possible approaches, emphasising a need for a joint force (taken to include a coalition component) that can ‘strike diverse targets inside adversary air and missile defense networks to destroy mobile power projection platforms’. It argues that forces that can ‘deploy, survive, operate, manoeuver, and regenerate in all domains’ and operate from ‘smaller, dispersed, resilient adaptive basing’ would be particularly important. And it talks about developing advanced autonomous systems and using artificial intelligence to gain a competitive military advantage.

Australia should identify the key operational domains in which it can contribute most effectively to countering A2AD at a reasonable cost and within a fairly short period. First, we should strengthen our anti-submarine warfare (ASW) capabilities, particularly for supporting expeditionary operations as part of a coalition alongside the US and other partners in the Western Pacific. That could involve enhancing our broad area undersea domain awareness by deploying fixed and deployable sensor arrays, combined with greater coordination with allies that operate ASW-capable ships and patrol aircraft in disputed maritime regions. Building and sharing a common operating picture of the undersea battlespace, not just in our maritime approaches but in areas such as the South China Sea, would be a useful regional response to the growing challenge posed by ever-quieter Chinese submarines.

Accepting a need to blunt A2AD will also demand that we quickly gain and maintain a knowledge edge in wartime. In future conflicts that’s going to become more challenging as China and Russia develop counter-space and cyberwarfare capabilities designed to attack our command and control networks, and as they exploit systems such as hypersonic weapons to compress time and space in the operational environment. So Australia needs to focus more on ensuring access to, and control of, both space and cyberspace as future operational domains.

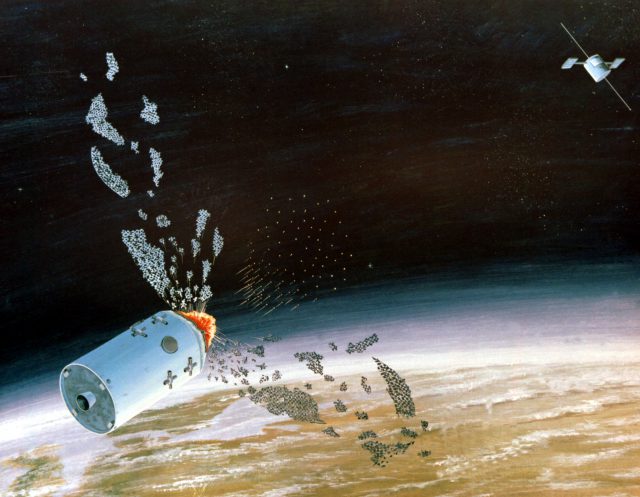

The space domain is becoming more important as joint and coalition forces increasingly rely on space systems to fight information-based warfare. To adapt the warning of Lord Montgomery of Alamein, if we lose control of space, we lose the war and we lose it quickly. Australia can contribute to US space resilience and boost deterrence in space by developing an ability to support the reconstitution of US space assets after an adversary’s counter-space attack. Thankfully, Australia seems to be ready to take steps to develop indigenous space capabilities, and looks to do more in the ‘space segment’. We are well placed to develop small satellites and offer southern hemisphere space launches in support of our allies. This would build on our ongoing contribution to space situational awareness as a member of the Five Eyes Combined Space Operations partnership.

The cyber domain is increasingly linked to space. Adversary counter-space capabilities are beginning to include ‘soft kill’ mechanisms, including cyberwarfare. Efforts to develop coalition-based offensive and defensive cyberwarfare capabilities can strengthen space resilience and threaten an opponent’s space systems, reinforcing the credibility of deterrence against counter-space attacks. Cyber might not be a tangible capability like warships, but winning in cyberspace is just as important as winning at sea.

We need to take some bold steps if we’re to respond effectively to a more dangerous security outlook. This will mean challenging some sacred cows in the defence white paper and IIP. That would be hard, but not impossible.

Acquiring new weapons and equipment would require boosting defence spending above the planned 2% of GDP, but we must be prepared to spend more, based on a hard-headed assessment of what capabilities are most relevant to the emerging operational environment.

Finally, we need to resolve the strategic disconnect between our recognition that the security situation is deteriorating and our relaxed attitude towards obtaining the equipment we need to defend ourselves. A prime example is the promised fleet of 12 future submarines, the first of which won’t reach the fleet until 2032 at the earliest. And we won’t have more than six until the mid-2040s. In the meantime, we’re dependent on upgrading what by the 2030s will be an ageing Collins fleet to keep pace with the rapidly changing undersea warfare capabilities of our adversaries. Fast-tracking the future submarine project would make a lot of sense given the challenges looming on the horizon.

The release of the Trump administration’s 2018 national defence strategy (NDS) in January highlighted a more dangerous threat environment with an assertive China and aggressive Russia at the top of US concerns. The document states that ‘it is increasingly clear that China and Russia want to shape a world consistent with their authoritarian model—gaining veto authority over other nations’ economic, diplomatic and security decisions’. China and Russia are certain to push back against the new US strategy, and thus the stage is set for a new period of major-power competition akin to the Cold War.

The US plans to enhance cooperation globally by developing ‘an extended network [of allies] capable of deterring or decisively acting to meet shared challenges of our time’. It also wants to reinforce ‘collaborative planning and deepen interoperability in a manner that could also include supporting foreign partner capability development to ensure an ability to integrate with US forces’. In the Indo-Pacific region, the US says it will build ‘a networked security architecture capable of deterring aggression, maintaining stability, and ensuring free access to common domains’ and ‘bring together bilateral and multilateral security relationships to preserve a free and open international system’.

Australia must quickly respond by talking to Washington about US expectations of its allies. We can’t afford to send mixed signals like we did recently, with defence minister Marise Payne supportive of the NDS one day, and foreign minister Julie Bishop distancing Australia from its key message the next. Our policy on the alliance has to be coherent and robust. The government should explore ways to strengthen the US–Australia alliance that enhance the likelihood of the NDS’s success and, at the same time, improve Australia’s security in a more contested environment.

The NDS refers to developing more survivable and dispersed basing arrangements in the face of a Chinese anti-access and area denial (A2AD) capability that’s increasingly long-range, accurate and responsive. Our contribution to that effort could include giving the US more access to Australian military facilities. For example, we could offer the US Navy home porting rights in Fleet Base West, and expand the enhanced air cooperation component of the US–Australia Force Posture Initiatives to a sustained presence, rather than only short-term rotations. That would enhance the survivability of US forces in the face of Chinese A2AD in East Asia, and reinforce extended deterrence below the nuclear threshold. It would also contribute to a more credible strategic deterrence posture for the US against China overall.

Strengthening our alliance arrangements will require us to discriminate between critical security interests and secondary concerns. If we’re going to help build the webs between the spokes in the ‘hub and spokes’ security arrangements, we must be careful to avoid commitments in which there’s a mismatch between our interests and the risks involved. That may call for some hard-headed choices about where, when and what we contribute. Making those decisions may be the most challenging aspect of developing a higher defence profile in Asia.

The Turnbull government has recently made good progress in facilitating closer defence relations with Japan, and is once again supporting a revival of the US–Japan–India–Australia ‘quadrilateral’ dialogue. These diplomatic efforts suggest useful pathways to playing a greater security role in Asia alongside the United States. But they do carry risks. We must not be naive about building ties that bind. We have to distinguish carefully between partners we want to cooperate with and those we seek a closer alliance with, because the latter group potentially entails defence obligations. These strategic conundrums aren’t new, but they’re becoming more acute and will force Australia to engage in a more mature strategic debate in more adverse circumstances. Our strategic holiday is coming to an end.

Indonesia also must, of course, be a priority for Australian defence diplomacy because it sits in the maritime fulcrum of the Indo-Pacific region, astride vital sea lanes and maritime straits. If China is to dominate Southeast Asia through the South China Sea, it ultimately must control Indonesian waters as well. The territorial dispute over Indonesia’s exclusive economic zone around the Natuna Islands, and China’s declared ‘nine-dash line’ which overlaps that zone, is likely to be a focal point for future crisis in Indonesian–Chinese relations.

Maintaining our strategic partnership with Indonesia is important because, as Stephan Fruehling noted recently, unless China gains access to, or control of, bases in Indonesia (as Japan did in 1942), the strategic geography makes it much harder for China to threaten Australia directly, at least in a sustained and substantial way. We should work alongside the US to boost Indonesian naval capabilities because a more powerful Indonesia that’s able to resist Chinese pressure on the high seas in turn limits Chinese territorial ambitions.

Taking on greater defence burden-sharing in Asia to support the US and counterbalance China will have significant defence capability and budget implications. I’ll consider those issues in my next post.

Strategic relations exhibit a sort of dialectic. Australia scans for regional developments that might affect its security, and regional nations assess Australia’s responses to its strategic environment and respond in accord with their own interests.

We can assume that China will pay close attention to any substantive changes in Australia’s defence policy, and respond. And some significant changes are being discussed. The growing strength of China and the putative decline in US power have engendered a spirited discussion of what Australia’s defence policy response should be. Adjustments to the level of funding for defence and changes to force structure are being promoted, and the acquisition of nuclear weapons is being discussed. None of that would go unnoticed.

China would be cognisant that Australia is already the 12th-biggest defence spender globally, and that Australia’s defence budget won’t reach its target of 2% of GDP until 2020–21. The defence budget currently accounts for roughly 6% of government spending. So, what Australia does with its defence dollar is already undoubtedly of great interest to China.

If, as widely suggested, Australia were to acquire an ‘anti-access and area denial’ capability—a costly restructuring of the ADF—it probably wouldn’t greatly worry China, especially if there was little chance of the US interfering militarily. The disparity in defence expenditure alone would give China confidence that it will continue to be more than a match for Australia’s conventional forces quantitatively.

In addition, China already possesses significant indigenous military-industrial capability, and the nature of its political economy allows China’s leaders to concentrate on quickly building high-capability, technologically advanced weapons systems.

China’s indigenous development of two fifth-generation fighters (the J-20 and J-31) and the advanced Beidou-3 GPS satellite constellation, and its investment in robotics and artificial intelligence, space programs, naval shipbuilding and aircraft carrier production are evidence of the country’s rapidly growing and modernising military-industrial complex. Beijing will easily also account for any qualitative improvements in Australia’s conventional forces into the future.

Whether or not Australia should go nuclear is altogether a different matter. Except in nations like China and Russia, the shortage of qualified engineers and operators is ‘one of the biggest challenges for the nuclear community’. Building a nuclear industry and workforce will in itself ensure that it’s a long process.

The discussion about Australia’s acquisition of nuclear weapons takes place largely in isolation from considerations of China’s nuclear weapons policy. China holds a relatively small number of nuclear weapons—at 270 warheads, it has slightly fewer than France and a few more than the UK.

Beijing’s stated policy is no first use of nuclear weapons ‘at any time or under any circumstances’. China regards nuclear forces as useful only for their deterrent effect. That is, ‘China will not attempt to win a nuclear war or use nuclear weapons to establish hegemony.’ Chinese strategic policy doesn’t see the use of nuclear and conventional forces as connected, and the Chinese ‘have complete faith in China’s no-first-use commitment and believe it greatly contributes to avoiding escalation’.

Nevertheless, unlikely as it may be, this longstanding policy might change. Some argue that just the existence of a nuclear arsenal and delivery capacity means it has to be taken into account. So if, contrary to the current understanding of Chinese nuclear policy, it was assumed that China would be willing to use the threat of a nuclear attack to deter Australia from using its conventional forces, it makes sense for Australia to have nuclear weapons.

Does it, though? In this situation, presumably, China would seek to prevent Australia from becoming nuclear-armed. What are its options? Beijing might seek to garner international support to censure Australia for not abiding by its commitments to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). If international moral pressure was unsuccessful, then China could up the ante by seeking a Security Council resolution, or even sanctions, against Australia. Economic, financial and trade sanctions against Australia by China—and most likely also by sympathetic pro-NPT nations—would have devastating effects on Australia.

Alternatively, or in parallel, China could take covert and overt direct action against Australia’s efforts to acquire a nuclear capability. That could range from cyberattacks to preemptive strikes on nuclear facilities, or from a maritime blockade of major ports to even a short war.

The key issue here is time. Australia has none. China has plenty. China’s conventional military power will always be more than a match for Australia’s. China would have ample opportunity to disrupt Australia’s acquisition of a nuclear capability, and probably at great cost to Australians. Sustained Australian political or public support for nuclear weapons would seem unlikely.

It has been suggested that if the risk of an attack from China is regarded as low, then ‘doing nothing is a perfectly credible response’. Alternatively, whether or not an attack from China is credible, to plan on a course of action that can never result in security for Australians doesn’t make strategic sense. The only thing more remote than an attack by China would be Australia’s chances of prevailing.

The long-term relationship with China can’t be built on planning for conflict. That could be a provocative, self-fulfilling endeavour. The future of Australia in East Asia lies in diplomacy, multilateralism and economics. The highest priority of our national policy should be avoidance of war involving China.

The US National Defense Strategy paper, which was unveiled by Defense Secretary James Mattis on 19 January, is a brutally frank statement of the threats facing America.

This is the Pentagon’s first new defence strategy in a decade and it carries the personal endorsement of Mattis, who proclaims that it is ‘my intent to pursue urgent change’.

The paper stresses that great-power competition, not terrorism, is now the primary focus of US national security. The US is emerging from a period of strategic atrophy, aware that its competitive military advantage has been eroding. Sixteen years of war, the longest continuous run of armed conflict in the nation’s history, ‘has created an overstretched and under-resourced military’, Mattis says.

The central challenge to US security is the re-emergence of long-term, strategic competition by what the paper calls ‘revisionist powers’. It is increasingly clear that ‘China and Russia want to shape a world consistent with their authoritarian model’—gaining veto authority over other nations’ economic, diplomatic and security decisions.

China is leveraging military modernisation, influence operations and predatory economics to coerce neighbouring countries and reorder the Indo-Pacific region to its advantage. Beijing will continue to pursue a military modernisation program ‘that seeks Indo-Pacific regional hegemony in the near term and displacement of the United States to achieve global preeminence in the future’.

Russia seeks veto authority over nations on its periphery ‘to shatter the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and change European and Middle East security and economic structures to its favor’. The subversion of democratic processes in Georgia, Crimea and eastern Ukraine is serious enough, ‘but when coupled with Moscow’s expanding and modernizing nuclear arsenal the challenge is clear’.

Thus, the US is facing increased global disorder with a security environment that’s more complex and volatile—including from rogue regimes such as North Korea and Iran—than any it has experienced ‘in recent memory’.

The new strategy commits the Department of Defense to build a more lethal joint force, strengthen alliances, and radically reform the department’s business practices. Mattis acknowledges that failure to meet these three key objectives will result in decreasing US global influence. And without sustained and predictable investment in its forces, the US will rapidly lose its military advantage.

For decades, the United States has enjoyed uncontested or dominant superiority in every operating domain. Mattis observes that in the past the US could generally employ its forces when it wanted, assemble them where it wanted and operate them how it wanted. Today, however, that’s no longer the case and every domain is contested.

Long-term strategic competition with China and Russia requires both increased and sustained investment because of the magnitude of the threats they pose to US security and the potential for those threats to increase in the future. Deterring or defeating such long-term strategic competitors is fundamentally different from managing the regional adversaries that were the focus of previous US strategies in the post–Cold War era.

So, what are the implications of all this for Australia? The great strength of this US defence strategy is the realistic geopolitical picture it paints of the world. It is decidedly grimmer in its outlook than either the 2016 Australian defence white paper or last year’s foreign policy white paper.

This should be a wake-up call for Australia. From Washington’s perspective, China isn’t the only threat. While Russia might be a weaker power than China at present, it is a more dangerous one and Canberra needs to understand that.

Moreover, while the Indo-Pacific is ranked ahead of Europe and the Middle East in the Pentagon’s list of key regions where aggression needs to be deterred, there’s no evidence that the US is capable of defeating two major-power regional contingencies—for example, China and Russia—at the same time.

As might be expected, the attention given to the strategic outlook is much more persuasive than the sections of the paper dealing with the future force structure and the urgent need to reform the performance of the Department of Defense. Little is offered other than generalities about the need to rebuild military readiness and field ‘a more lethal force’.

As for reform of the department, there are lots of meaningless modern management words used about the need to ‘drive budget discipline and affordability to achieve solvency’ and ‘streamline rapid, iterative approaches from development to fielding’. But the fact remains that the Pentagon has for decades resisted introducing a culture of performance in which results and accountability really matter.

But it isn’t only the Pentagon that’s recalcitrant in this regard. As Mattis said at the launching ceremony, ‘no enemy in the field has done more harm to the readiness of the US military’ than the combined impact of defence spending cuts, worsened by operating under continuing congressional resolutions for nine of the last 10 years.

All of this suggests to me that Australia needs to refocus on its own region of primary strategic concern, building the military capability to ensure that we can deny our vulnerable approaches to any potential adversary—including China.

Paul Dibb and Richard Brabin-Smith recently opined that our strategic situation has changed for the worse and that the warning time clock is ticking. I think they’re right. We were able to cruise through the post–Vietnam War period without doing too much thinking about our strategy or force structure (though don’t tell Paul or Brab I said that) because there was nothing major to worry about in our hemisphere. That’s clearly far from the case now. The question is, then, ‘What do we do about it’?

Dibb and Brabin-Smith’s prescription is for an overhaul of our force preparedness, with a possible future step of developing an anti-access and area denial (A2AD) strategy. Hugh White’s response mostly agrees, but cautions that a lot of thought, work and money—he has previously suggested in excess of 2.5% of GDP—would be required to develop the forces that could withstand a Chinese assault on Australia. He also makes the important observation that the ADF force structure would look very different from the one we’re in the process of spending a couple of hundred billion dollars on. White is a long-term advocate of a ‘focused force’ that is more heavily weighted towards A2AD.

But before we can start redesigning our military forces, or doubling down on defence spending, we need to come up with answers to some fundamental questions. Why would China attack Australia? If it did, what form might an attack take? And—the biggy—how do we propose to counter China’s nuclear arsenal?

A possible answer to the first question is that prudent planning worries more about capability than about intent. If a regional country has the capability to attack us, so the reasoning goes, then we’d better be able to defend ourselves should they choose to do so. ‘Capability over intent’ has been something of a mantra in Australian defence planning for decades now, and it was a handy excuse to keep buying replacements for ageing force structure elements in the absence of any obvious hostility in our extended neighbourhood.

But that’s a poor reason to divert hundreds of billions from hospitals, schools and the NDIS. Optimists can make a plausible case that China already has ready access to Australian natural resources and is well down the track to securing its own part of the world from external threats. They might also add that nothing in President Xi Jinping’s China vision seems to suggest expansionism beyond those territories that China has claimed at various times throughout its long history.

But I think there are plausible ways in which Australia and China could fall out badly enough to make the use of armed force possible. The most likely is by Australia taking the American side in a conflict between China and the United States. But even if the US largely opts out of Asian affairs in the future, we could still get into China’s sights. It would be morally questionable for Australia to continue to do business as usual with Beijing if, for example, China attacked Japan or Taiwan—both of which are credible possibilities—or another neighbour, such as Vietnam. An Australian embargo of exports to China could put us on a collision course (as it did with Japan in 1941).

So Dibb and Brabin-Smith might be right about the possibility of a future conflict with China. Or at least it’s plausible enough to require defence planning. The next question is what sort of conflict might we find ourselves in? Here’s where a little more caution is required. Australian strategists are much too glib when talking about ‘our region’. Geography still matters, especially where power projection is concerned. Listening to local debates, you could sometimes be forgiven for thinking that Australia and China share a Colorbond fence down the sideway. To seriously threaten Australia with conventional force, China would need to develop considerably more long-range power-projection platforms than it currently has, or even has planned. This isn’t Europe. We don’t share a land border with our potential adversary—there’s an intercontinental distance between us and China.

Realistically, rather than invasion or large-scale disruption, we’re talking about strikes against Australian targets of the sort that the US can launch today from its surface vessels, long-range aircraft and submarines. To hedge against that, we’d need to do exactly what China has been busy doing for the past 20 years to counter possible American strikes: develop an A2AD capability. In that respect, Dibb, Brabin-Smith and White are spot-on—the defence force needed to do that is quite different from the one we’re about to invest in. For a start, we wouldn’t be building a dozen large warships. We would be building more submarines, aircraft and missiles that could threaten Chinese power-projection assets. (Incidentally, I think we could do that with a defence budget not much bigger than today’s if we were prepared to make the tough calls on priorities.)

But there’s still one thing missing. China is a nuclear power. If it really wanted to threaten Australia, it wouldn’t be limited to threatening strikes with relatively small conventional weapons. That’s the element that sets the Australia–China scenario apart from today’s China–US dynamic in which both sides have nuclear weapons. If we seriously want to be able to independently hold China at bay, we need to counter a nuclear threat as well as a conventional one. Following their respective logics through to their conclusion, Dibb and White have both discussed the nuclear issue in recent pieces, but they both equivocate on actually suggesting that we need to go down that path. Dibb says:

There is no present requirement foreseen for Australia to develop a nuclear weapons capacity. But the history of advice to successive governments suggests, should our strategic circumstances look like deteriorating disastrously, it might be prudent to revisit reducing the technological lead time.

In his new Quarterly Essay, White says:

The chilling logic of strategy therefore suggests that only a nuclear force of our own, able credibly to threaten an adversary with major damage, would ensure that we could deter such a threat ourselves.

But he then steps back, neither ‘predicting nor advocating that Australia should acquire nuclear weapons’, while allowing that ‘it is untenable to think that this won’t mean the question will have to be re-examined’.

The coyness, and willingness to defer grappling with the logical conclusion of their arguments, effectively leaving it to future strategists, is surprising. Either our defence prospects have changed so much that we need to worry about being attacked by a nuclear-armed major power and drastically change our defence policies, or they haven’t. It’s true that extra conventional arms will provide additional deterrence in some scenarios, but almost by definition they wouldn’t involve an existential threat to our sovereignty.

There is a serious strategy discussion to be had and the recent discussion is a start, but it’s dangerously incomplete. Pursuing the force structure changes suggested by White could result in us spending many billions of dollars for little extra security. The key question, which we shouldn’t dance around, is whether we judge the risk of an attack from China to be high enough and serious enough to warrant developing an independent nuclear deterrent. Conversely, if we judge the risk to be small, doing nothing is a perfectly credible response. Sitting in between—worrying about the prospect but taking inadequate (though prodigiously expensive) steps to hedge against it—doesn’t seem very sensible.

Times change and we change with them, as the saying goes. Much the same could be said of warning times: as our strategic circumstances change, so we should reassess the consequences for contingencies that the ADF might be involved in and their associated levels of warning.

Warning time is a key concept. It has a pervasive effect on defence planning, being a strong determinant of the force structure, including the purpose and structure of reserve forces. It is a similar determining factor for the readiness spectrum of the ADF’s force elements and the associated levels of sustainability. At least in theory, it should have a strong effect on defence policy for industry. Perspectives on warning time are integral to the assessment and management of strategic risk. If views on warning time are too optimistic, the nation is subject to an inappropriate level of risk; if too pessimistic, then we incur unnecessary expense with little compensating benefit.

Over most of the past 40 years, Australia has been able to take a relaxed approach to warning time. Starting in the 1970s, the key observation was that the potentially hostile capabilities that might be used against us were at only modest levels. Further, it was difficult to imagine an issue of sufficient weight to cause military action against us to be contemplated. These conclusions led to the concept of the core force and expansion base: the capabilities of the ADF would be sufficient to handle those lesser contingencies that might arise in the shorter term, and be the basis for expansion in the event of serious strategic deterioration in the longer term.

This approach to defence policy accepted that motive and intent could change relatively quickly, given a sufficient catalyst, but that it would take an adversary considerable time—10 to 15 years—to develop the level of capability, including doctrine, necessary to mount a serious assault on Australia. Over the years, the structure and preparedness of the ADF evolved to be consistent with this policy, although the diligence with which these principles were applied tended to depend on the level of defence funding that was available at the time. Development of the force structure also reflected the priority for strong maritime forces and the defence of the sea–air gap to our north. While some elements of the ADF were ready to move within hours, such as counterterrorist forces, most elements were at a more relaxed state of alert, with readiness times varying between weeks, months and, in the case of parts of the reserve forces, years. Training levels and sustainability were influenced as much by the need for the ADF to meet high professional standards as by considerations of warning time.

In our recent paper, Australia’s management of strategic risk in the new era, Paul Dibb and I argue that times have indeed changed, and that it is now necessary to reassess warning times and the consequences for preparedness and the force structure. The basic proposition is that with the rise of China and its ambitious program of modernisation and expansion of its armed forces, it is no longer the case that potentially hostile forces have only modest levels of capability. Further, these capabilities will continue to increase over the years ahead. This situation takes away the main argument of previous decades that contingencies in the shorter term would necessarily be at a low level and that warning times for more serious contingencies would be long. This is not to ascribe to China (or anyone else) the motive and intent to conduct military operations against Australia; that is a separate argument. But it is to recognise that warning times based on assessments of motive and intent will necessarily be shorter—and more ambiguous—than those based on evidence of the absence of capability, as was so strongly the case in earlier decades.

It is important not to be alarmist: contingencies, least of all serious ones, are not waiting for us around the next corner. Nevertheless, Australia’s new and evolving circumstances will be more demanding. At the very least, the prospect of shorter warning times calls for a thorough review of the readiness and sustainability of the ADF. This review should include the expansion base, reserves and industry in its scope. In our paper, we suggest that areas which need attention for the shorter term include a sustainable surge capacity for round-the-clock operations, munition stocks, fuel resupply (especially in northern Australia), and forward operational bases. Even if the government cavils at the expense of higher levels of preparedness or is otherwise not persuaded by the arguments, Defence should at least identify the steps that would need to be taken to position itself to respond to contingencies within whatever warning time turns out to be available.

This week, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute turned 16. Happy birthday! Yet once more this seems a birthday in relative isolation. The institute itself remains keen to communicate, but increasingly I worry that few are listening or talking back.

As Robert O’Neill explained in a blog post last year, ‘When I began [as ASPI chairman,] Prime Minister Howard emphasised to me that he needed contestable advice … The Government also wanted another dialogue partner in the public debate.’

ASPI continues on that mission, but outside a few veritable institutions such as the Lowy Institute or my own Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at the ANU, it’s not clear that dialogue and contestability exist. Even if the turmoil in world events has led to an uptick in media op-eds, the most important institution for debate, our federal parliament, remains largely silent.

Australia’s political system is deliberately adversarial. We have two chambers, both divided into halves. In each chamber, a formal position of ‘Leader of the Opposition’ exists. Yet in recent years one of the holders of that post has taken to declaring that ‘keeping our people safe is above politics. The security of our nation runs deeper than our political differences’.

The reason for the silence and desire not to argue or oppose is bipartisanship. As Stephen Conroy, Labor’s former shadow defence minister put it in a speech to an ASPI conference, ‘Labor strongly believes that the best outcomes for Australia’s national security are achieved through consensus and bipartisanship. This was our starting point when considering the 2016 Defence White Paper.’

Whatever the good intentions that sentiment derives from, the outcome has not been a ‘constructive and engaged’ discussion, but silence. Despite the strategic turmoil of our region, we have only a weak idea about what the Labor party accepted or rejected from the last white paper. And while the strictures of government require some modicum of discipline, it’s notable how little we’ve heard from government on how to update that document in light of worsening security trends. As I argue in a new report, our current desire for bipartisanship is putting our country at risk.

I don’t blame the politicians entirely for this silence. I know they take seriously the importance of defence policy decisions and the risks when sending the ADF to fight. Yet they’re rarely allowed to publicly express their concerns or differences over how to achieve strategic goals. Polling shows that two-thirds of the Australian public prefer a bipartisan approach. Equally, many former members of the ADF and expert commentators regularly call for our politicians to ‘keep the politics out of it’.

This not a new phenomenon, as Howard’s support for ASPI in 2001 indicates. Australia’s bipartisanship on national security and defence issues emerged in the early 1980s. Yet where that was a negotiated truce between the left and the right, with the former accepting the US alliance and the latter a diffused policy that prioritised Asia, today it has become a straitjacket that restricts our national ability to deal with the evolving regional order.

Ultimately, that’s bad strategy. There’s simply too much going on, too many issues to be across, too many causes and effects to link together for any one person to understand and grapple with it all. Yet that’s what our system requires. The man or woman occupying the prime minister’s office must make those choices. The inputs to their decision, resting on the Department of Defence and a few outside voices like ASPI, remain almost as narrow as they were 16 years ago.

Not only has our parliament’s silence impeded our ability to think through what needs to change, it also hurts our capacity to ensure the right ideas remain. As Andrew Shearer and Michael Green remarked a few months ago, of all the challenges facing the ANZUS alliance, ‘[p]erhaps most important of all is the need to renew the Australian public’s understanding of the essentiality of our alliance’. Under President Trump, the alliance is suffering a thousand small cuts, yet bipartisanship keeps the supporters effectively gagged.

In a quieter time and place, perhaps it wouldn’t matter. We could place our faith in the talented professionals across our civilian and military agencies to advise the prime minister and assume that was enough. But these are not quiet times. Many of the big defence and security decisions are political: how do we assess China’s intentions, would the Australian people support deployments to protect Japan or South Korea, should we rush in new defence capability, and what do we do if the US continues to be erratic and distracted?

Since 1901, the Australian prime minister has had responsibility to decide national strategy and defence policy. It has worked well and I see no reason to change it. But what’s different today from earlier periods of strategic turmoil, such as 1905–13, or 1956–76, is that today our parliament and wider society aren’t helping to inform the PM’s decisions.

ASPI can do only so much. To truly have ‘contestable advice’ and a dialogue partner for the government, we need our parliament to throw off the shackles of bipartisanship and debate freely and openly the changing world before us and our path to security. Let’s hope ASPI’s next birthday is a more crowded affair, with more voices heard around the cake.

It really does make a difference who occupies the White House. Acknowledging that point seems beyond many commentators and policymakers in Australia. Yet, failing to recognise how important individuals can be may leave allies floundering as they struggle to keep up with the consequences of the Trump regime.

The great hope in Australian policymaking circles, of course, is that President Trump will be socialised by the institutions, traditions and practices of which he is now the most pivotal player. Trump’s recent address to Congress was seized upon by optimists and apologists alike as evidence of a more “presidential” style as the leader of the free world recognised the responsibilities of the Oval Office.

Within days that comforting illusion had been shattered by a series of ill-considered Tweets about his predecessor—someone who actually did look presidential and was the personal embodiment of many of the virtues and values that are frequently part of the rhetoric, if not the practice, of American policy inside and outside its borders. Indeed, for all the criticisms of Obama’s supposed indecisiveness, he looks better by the day when contrasted with the present incumbent.

The big question for observers of American politics—and the world more generally—is: Will Trump transform Washington more than it changes him? The assumption that the American system’s checks and balances, much less its political culture will rein in Trump and his advisors looks increasingly like wishful thinking.

Trump and his strategist-in-chief, Steve Bannon, appear to have a visceral distrust of the very institutions of government that they’re conspicuously failing to manage effectively. For Bannon in particular, the existing institutions of government are actually part of the problem; a “deep state” filled with political opponents who have to be torn down before something more effective and politically amenable can be put in its place.

Unfortunately for the rest of the world, the impact of that agenda won’t be confined to the US itself. On the contrary, America’s continuing economic and strategic importance means that many states are likely to suffer significant collateral damage as the policy revolution takes hold in the US.

Given that the Trump administration has only been in power for a couple of months its impact has already been remarkable. Trade deals have been shredded in favor of 19th century mercantilism; allies have been put on notice about America’s heightened expectations. In Trump’s world, it’s not even clear what the distinction between friend and putative foe actually is, as the administration’s murky ties with Russia remind us.

Trump’s admirers might claim that his famously transactional approach to policymaking rightly privileges America’s neglected national interest and brilliantly wrong-foots opponents. Critics might argue, that the entire administration lacks focus, much less a grand strategy, and blindly lurches from one Tweet-induced crisis to another. Even America’s closest friends should be considering their options in such circumstances.

In Australia’s case we ought to remember we’ve been here before. George W. Bush’s monumentally misguided decision to invade Iraq is now widely and rightly seen as one of the greatest and most unnecessary strategic blunders of recent years. Not only did it destabilise the Middle East in ways that are still reverberating with disastrous consequences, but it also sucked Australia into a series of conflicts that had little immediate strategic relevance.

At least Bush and his advisors looked like the sort of “rational actors” that populate the pages of international relations textbooks. The policies of the likes of Wolfowitz and Cheney may have proved to be delusional and hubristic, but they were in keeping with a well-established American approach to strategic policy generally and to the Middle East in particular. Even Jimmy Carter had promised to do whatever might be necessary to maintain American influence in the Persian Gulf.

The Trump administration looks positively irrational by contrast. It’s not just the absence of a clear narrative about the administration’s intentions that’s so concerning for friend and foe alike, but that the Trump regime seems to groaning under the weight of its own internal contradictions. Questionable, inexperienced and/or compromised appointments, flagrant conflicts of interest, and a famously thin-skinned president with a seemingly limited attention span and little knowledge of international affairs add to the overall sense of chaos and ad hocery.

We’ve barely begun a Trump era which could, theoretically at least, go on for another eight years. It’s hard to imagine what the world might look like if that happens. At the very least it’ll be a sobering reminder to academic observers that in the age-old debate about the relationship between structure and agency, agency really does matter—even if it doesn’t really know what it’s doing.

This piece is drawn from Agenda for Change 2016: strategic choices for the next government.

The defence of Australia’s interests is a core business of federal governments. Regardless of who wins the election on 2 July, the incoming government will have to grapple with a wide range of security issues. The Australian Strategic Policy Institute will soon release a Strategy report which provides a range of perspectives on selected defence and national security issues, as well as a number of policy recommendations. (Canberra-based readers can come along to the report launch on Tuesday 7 June.)

ASPI produced a similar brief before the 2013 election. A comparison of this year’s edition with the 2013 Agenda for Change paper shows that there are some enduring challenges, such as cyber security, terrorism and an uncertain global economic outlook. Natural disasters that affect large groups of people are a constant feature of life on the Pacific and Indian Ocean rim.

Some of the problems we wrote about in 2013 have already been addressed by decisions taken by the outgoing government—though it’s rare to be able to lay complex problems to rest in perpetuity. In February this year we got a Defence White Paper that set out over $150 billion of future investment, which should ameliorate the looming defence resourcing issues we identified back then. Similarly, the Department of Defence is undergoing a root and branch reform following the 2015 First Principles Review, which includes measures that address some shortcomings we noted in the old structure. And we’ve just had the release in April of a Cyber Security Strategy document that sets out the way ahead for the government’s response to a growing online threat.

There are also some challenges that didn’t seem so acute only three years ago but need attention now. Recent events in the South China Sea have markedly ratcheted up regional tensions. North Korea’s increasingly sophisticated nuclear and missile programs continue to destabilise North Asian security. And ISIS has emerged as a serious military threat in the Middle East and an exporter of global terrorism, both by sending operatives out to other countries, and by recruiting locals through an online propaganda program.

The incumbent for the next term of government will have to deal with these issues—and probably some that aren’t obvious now. For example, the incoming Abbott Government could scarcely have thought that an airliner shot down over the Ukraine would provide an early test of its approach to national security. We hope that our 2016 Agenda for Change report provides a good ‘incoming brief’ of the nation’s security issues as we see them today, but we recognise that events will overtake some of our prognostications and policy recommendations. We’re not likely to be short of issues to analyse in the years to come, and ASPI will continue to provide its blend of strategic analysis and policy development, not just for government, but to inform the public discussion of important issues.

In the lead up to the launch of Agenda for Change 2016, The Strategist will present a series of posts drawn from the publication.