Australian policymakers’ attitude to the role of northern Australia in the nation’s defence mimics a cicada’s life cycle. For a brief period, it’s out in the world, flying around and making a huge amount of noise, just long enough to mate and create the beginnings of the next generation. That noise and flurry is followed by years of quiet gestation and subterranean tunnelling by the new generation, before the cicada’s brief time in the sun returns.

The last time real attention was paid to what our regional environment means for defence in the north of Australia was in Paul Dibb’s 1986 Review of defence capabilities and the 1987 defence white paper. Following that work, the Australian government invested billions of dollars in bases and bare base infrastructure in the north, with a real focus on the Northern Territory.

RAAF Base Tindal became and remains a core base for air force fighter jet operations, and the army took real steps to create a functional and serious presence in the north. An arc of bare bases was constructed—like RAAF Base Scherger on Cape York and RAAF Base Learmonth in Western Australia.

The other big initiative in our north has been the joint Australia–US force-posture work that started in 2011 and has brought rotating US Marine deployments to Darwin that exercise with our military and various regional militaries. That welcome set of initiatives is more about US engagement in Australia and our region than about how we will meet our own defence needs.

A problem for this policy area is that commentators have a habit of getting very simplistic very fast. If you advocate a greater defence presence in northern Australia, you’re just resurrecting the Dibb review and have an overdeveloped sense of paranoia about small numbers of men in black raiding Darwin infrastructure and Territorians’ cattle stations.

If you see the value of drawing in the more advanced infrastructure and larger population centres in southern Australia and on the east coast, you’re just one of those defeatist, pre-Federation types who wants to withdraw south of the Brisbane line during conflict and wants to see all money and activity flow to your own favoured state.

And the US presence has brought a new layer of discussion to the debate. Unfortunately, this is often about the risks and advantages of having US forces on Australian territory and the pragmatic issues involved—like who funds what, and the regimes for managing the behaviour of visiting and local militaries.

None of this introspection engages much with the real strategic drivers that make a serious Australian defence presence in our north a compelling and increasingly urgent matter of strategic policy and capability planning.

Unsurprisingly, as a geographer and a strategic analyst, Dibb got some big things right that still matter. Australia’s defence must take advantage of our geography, and any credible Australian military must be able to project and sustain substantive levels of force from Australia’s northern land mass and offshore territories.

Similarly, defence planning should indeed take advantage of the deeper infrastructure, industrial support and demographic bases in our southern and eastern population centres to produce and sustain the complex systems that make up modern defence capabilities. The deep technical ecosystem required to operate and sustain the range of advanced platforms and systems the ADF has and is acquiring can’t just be a parochial effort out of any given state or territory. It requires a national approach to industry policy and to skills and workforce.

But defence in the north has, like the cicada, moved back into the light. And that’s because of Australia’s changing strategic environment.

That environment is characterised by two big trends.

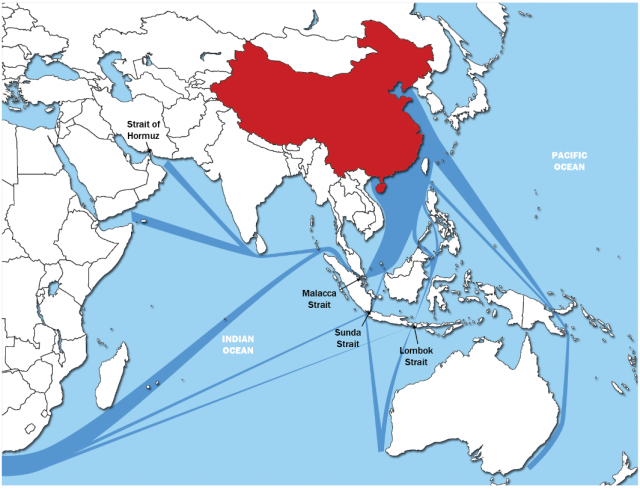

First, regional nations continue to get richer and more capable, including in their ability to project military power within and beyond their own territories—meaning that near-region partners like Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore are becoming more important in Australia’s security and diplomacy. Australia needs to do more to engage with these partners, and the north of Australia is a gateway for that to happen.

Second, great-power competition and potential conflict have returned to the forefront of world affairs. China and the US are now actively engaged in deep strategic competition and arm-wrestling over political, economic and strategic relationships and technological dominance across our Indo-Pacific region. There are credible prospects of a major military conflict between these great powers over the next couple of decades, which, if it happens, will most likely spill beyond a bilateral conflict into a wider regional war.

The north’s significance in this context is that it’s the closest point from which Australia can project and sustain military force. And the expanse of territory means that it allows dispersal of forces and power projection from multiple places.

The size of the north makes it more important as a counter to the increasingly lethal and long-range systems that can target single points of failure in an adversary’s defence effort (think Guam or Hainan Island as missile-aiming points).

So, to make the north a growing strategic advantage in our defence planning, we need to respond to these bigger strategic trends. We also need to take advantage of the growth in population, industrial capability and infrastructure that has occurred in the north since the foundational thinking of the Dibb review.

That means thinking about how the north can empower and deepen our broader regional relationships. The Northern Territory government’s close relationship with Indonesia should be part of this, as it can help pave the way for growing defence and other industry connections out of the north with Indonesia.

It also means doing what the US Marines in Darwin do: using the regional proximity to increase bilateral and regional exercising and engagement with partner militaries.

Proximity matters. Even for fast surveillance aircraft like the RAAF’s new P-8 Poseidons, the transit time from Edinburgh in South Australia to Darwin is over three hours, and that means we get some six hours’ more range and endurance up into our region if we operate out of Darwin instead of RAAF Base Edinburgh.

The real thinking, innovation and resourcing, though, need to be driven by the implications for Australia of the growing great-power competition and geopolitical conflict that we’re seeing. Major conflict is a worst-case scenario, but that’s why governments invest in high-end militaries.

Being able to sustain and operate Australia’s military in the event of a wide regional conflict involving the major powers entails a big shift in priorities and investment that must include our northern presence and infrastructure.

Despite the base reinvestment program in the 2016 defence white paper, our military would still struggle to sustain lengthy operations from the current northern infrastructure.

A simple but key example is fuel supply for air operations out of Darwin and Tindal. Fuel tanker convoys on the highway cannot be an adequate solution. Similarly, our bare bases need to be configured to be able to operate and support an increasingly wide range of capabilities, not just the big platforms like P-8 aircraft or even the joint strike fighter. They also need to be hardened and have dispersed operating areas so that they can continue to function in the much more lethal threat environment of modern long-range war.

Both strategic trends mean it’s time to have a new discussion about the nature and level of our defence presence in the north. The paradigm has changed since 1987, so what’s the new framework for thinking about a future-ready ADF presence? Industry needs to be an active participant in this discussion and the resulting actions.

It’s time for the cicada that is our northern defence thinking to take wing again. Let’s stretch the time it has in the sun long enough to understand and make the necessary changes.