Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

The government has made its long-awaited decision on the first phase of LAND 400, Defence’s megaproject to acquire new armoured combat vehicles. And the even bigger decision on the future frigate is likely soon to follow.

The successful tenderer for the combat reconnaissance vehicle was Rheinmetall’s Boxer. It’s not clear yet why the government chose the Boxer over its competition, BAE’s AMV35. While the prime minister stated the number of jobs that would be created, he said that the selection was the result of a rigorous testing process that assessed the Boxer as ‘the most capable vehicle’.

Minister for Defence Industry Christopher Pyne was also at pains to state that the government went with Defence’s recommendation and that ‘politics played absolutely no part in the decision’. If that’s the case it was a remarkable decision, but one made for the right reasons.

It’s no secret that major defence capability decisions are being made in a defence industry environment that’s very different from when these projects were first developed. It can be amazing what a difference a few years can make.

The Abbott Coalition government came to power with a defence industry policy that was essentially indistinguishable from its broader industry policy. Subsidies were a bad thing, and just as the government wasn’t going to subsidise Australian industry to build cars, so it wasn’t going to pay extra to build military equipment in Australia. Defence’s investment plan was first and foremost about military capability, not nation building or supporting local industry.

Times (and prime ministers) have certainly changed, and changed quickly. The government released a new Defence Industry Policy Statement as part of the 2016 white paper. More recently, the government released the Defence Export Strategy aimed at boosting Australian industry’s share of the global market. Defence industry featured as a major source of ‘jobs and growth’ in Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s election campaign.

By all accounts the big primes competing for the combat vehicles (and frigates) have gotten the government’s message that if they want to have a shot at winning, in addition to having a capable platform they also need well-developed Australian industry plans that maximise Australian industry participation in both the build and sustainment supply chains.

The contenders have thought hard about how to get Australian industry involved in the build and, perhaps more importantly, in the through life sustainment of the vessels and vehicles. If these plans provide a better understanding of the cost, schedule and risk implications of Australian industry participation, that’s a good thing.

Unfortunately other audiences have gotten other messages, which has led to rather undignified boosterism from state governments and local media. To the extent that their claims to be the most deserving rely on any arguments other than state-based parochialism, it’s that Australian content—whether dollars, jobs or steel—should be the ultimate determinant in the government’s selection.

That would be the worst approach to take. These decisions are too important to get wrong. The frigates and combat vehicles will provide the core of Australia’s maritime and land combat capability well into the second half of this century. For better or worse, the Australian Defence Force will have to live with the outcomes of these decisions for decades. Each decision must be made on the basis of which contender provides the best balance of capability, cost and risk. If, in the 2030s and 2040s, the government of the day needs to commit them to achieve its goals, the question of how much Australian steel they used will be irrelevant.

The reasons that Defence and subsequently the government chose Boxer over the AMV35 will take some time to emerge. By all accounts both contenders were viable candidates and a huge leap in all aspects of capability from the ASLAV vehicles that the project is replacing. From Ben Roberts-Smith’s recent comments, possibly on the basis of leaked selection trials, the Boxer performed better under blast testing, which is perhaps not surprising since the Boxer is bigger and heavier, carrying more armour. The Boxer is a more recent design and appears to have a more advanced suite of self-defence systems and sensors for all-round situational awareness.

All of this means that the Boxer is likely to be more expensive. Until now the government has stated that it would acquire 225 CRVs, but its Boxer announcement states that only 211 vehicles will be acquired. It may be that in its overall calculus of cost, capability and risk, the government chose quality over quantity. This would be quite consistent with Australia’s historical approach.

The project cost announced by the prime minister of $5.2 billion is beyond the upper end of the $4–5 billion budget in Defence’s Integrated Investment Program. It would be interesting to know whether Defence had to find money in other projects to top up LAND 400 to allow it to acquire sufficient vehicles.

Whatever the case, making a decision that isn’t squarely based on capability doesn’t only put Australia’s servicemen and women at risk. It also potentially denies the government itself of the capability it needs to meet its core responsibility of defending Australia.

So far it looks like the government is making its decisions for the right reasons.

PS. For those who have just arrived from Mars, the AMV35 was to be assembled in Victoria. The Boxer will be assembled in Queensland, with substantial input from Victorian businesses. After the initial disappointment wears off, Victoria’s $373.6 billion economy will likely survive.

One part of my talk at the Australian Defence Magazine’s annual defence industry conference that didn’t make it into my previous post was a digression about the recently released defence export strategy. Rob Bourke’s recent post picked up on a few of the points I covered, so I’ll confine myself to a critique of the government’s stated aim of making Australia a ‘top ten’ supplier of armaments.

As Rob already pointed out, establishing a baseline of the current level of defence exports isn’t as easy as you might hope. There’s no single unambiguous source of data, and the $1.5–2 billion figure in the strategy isn’t obviously relatable to specific products. Defence used to issue an annual report on Australian arms exports, but that stopped after 2003–04. More recently the Defence Export Controls office has put out a statistical report of export permit applications and their outcomes. That data is incomplete and potentially misleading for two reasons. First, not every approved application results in exports to the full value of the approval. Second, it’s not mandatory for exporters to provide the department with the value of the goods or services in question—some do and some don’t.

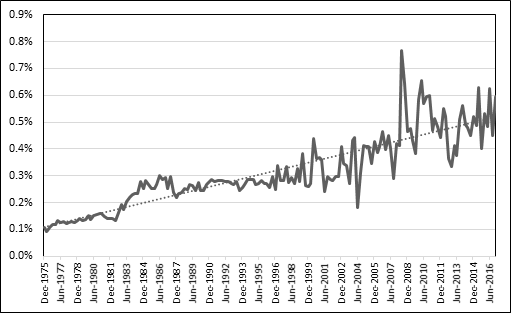

With all those caveats, it’s hard to do solid analysis—at least if we’re depending on accurate in-year values. But it’s still possible to make some observations about relative performances over time and in comparison to other countries. The necessary data resides in the arms transfer database maintained by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). Their bespoke methodology for denoting the value of arms sales includes a ‘trend indicator value’ (TIV) that ‘represent[s] the transfer of military resources rather than the financial value of the transfer’. The SIPRI numbers have been misread by some as dollar figures, but it’s not a bad way to smooth out the quirks of the international arms market—such as arms deals that aren’t cash transactions, but involve complicated trade arrangements in part or whole payment.

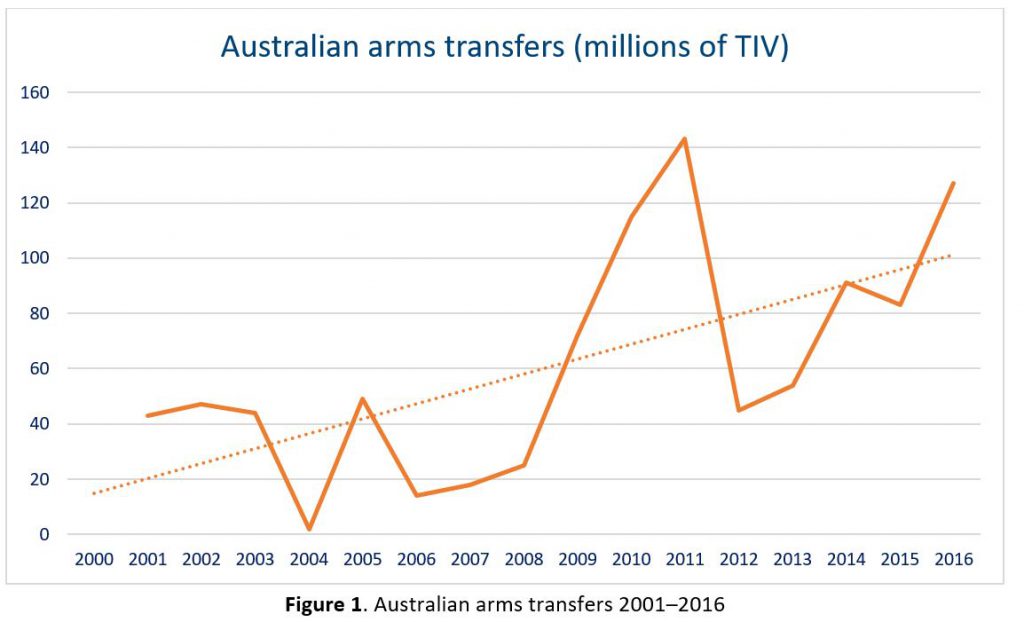

Figure 1 above shows Australian arms exports since 2001, in TIVs. The data is volatile, but there’s an underlying average annual increase of about five million TIVs (dotted line). So the government’s defence export drive builds on an existing trend. (Although that reasonably strong long-term growth raises the question of just how much additional government assistance is needed.) More careful management of existing assistance—better marketing and a focus on matching local production to customer needs—could boost the market for Australian-produced weapons.

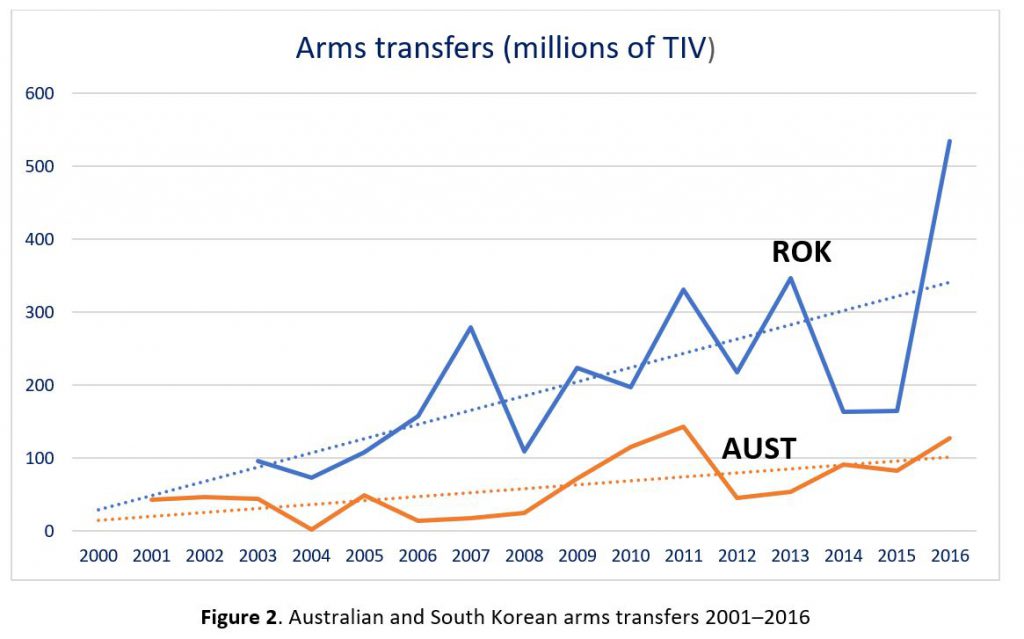

So far, so good. But Australia isn’t the only country aiming to sell more defence materiel to help grow its economy and offset the cost of producing its own weapons. Many of the countries on the identified list of future market growth are trying the same thing—especially the UK and the US. To see how hard it might be to move higher up the ladder, Figure 2 shows the comparative data for Australia and South Korea (ROK). I chose South Korea because it’s a country not dissimilar to Australia in terms of size, and because at number 15 it sits pretty much midway between Australia’s spot at number 19 and the top ten spot we’re covetously eyeing.

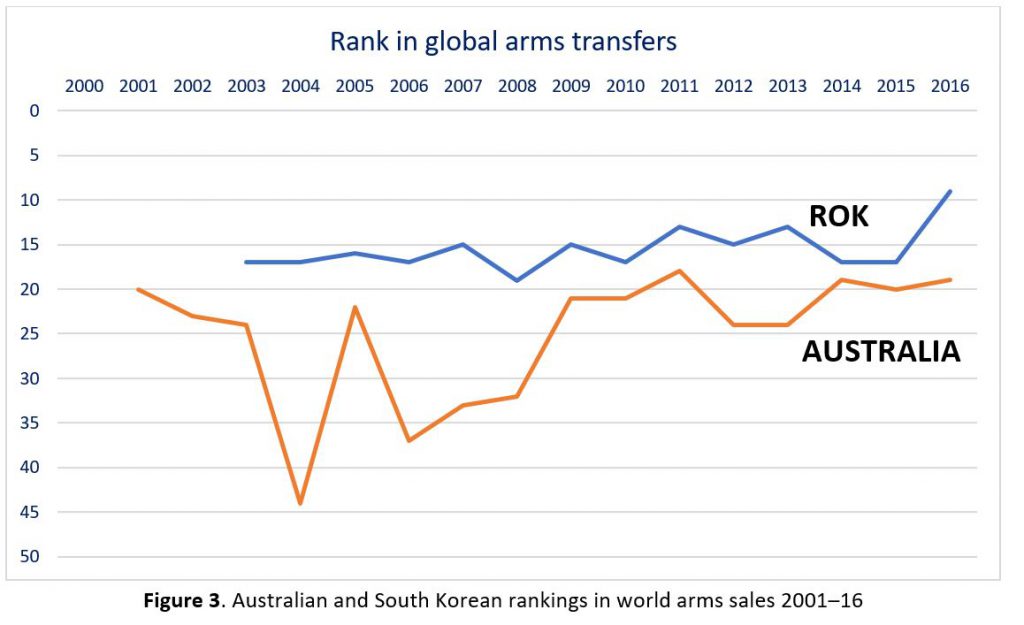

Figure 3 shows the ranking of the two countries over time. The ROK has been between 19th and 13th for the past 18 years, making a big leap last year into 9th place. That was almost entirely due to one big sale of trainer aircraft to Iraq—about which more later.

The main takeaway from those last two charts is that the ROK has mostly trod water in the rankings since 2001, despite increasing its arms sales more than twice as fast as Australia. To get past the ROK (and other intervening nations), we’d need to at least triple the growth in our sales over an extended period. It’s possible, but I wouldn’t bet on it.

To see how hard it can be to move relative to other countries all trying to do the same thing, back in 2006 the Howard government had ambitions to make Australia an energy exporting ‘superpower’. At the time Australia was in 8th place on the world export rankings with a market share of 2.4%. A decade later we were still in 8th place with the same market share—and that’s in a field where we have comparative advantages.

Finally, it would be remiss not to mention ethical concerns about arms sales. Aid and other groups have been vocal in their opposition to the new push. There are moral hazards in selling weapons, such as exported materiel turning up on the ‘wrong’ side of a conflict or being used in questionable operations. (And not just sales—helicopters gifted by Australia to PNG in the 1990s ended up being used in offensive operations in Bougainville, despite the PNG government previously agreeing to quarantine them from such use.)

And there are hazards even if nothing gets used ‘incorrectly’. Some of the biggest companies in the defence world—including some we deal with—have been found to have engaged in illegal deals, particularly when selling to countries where corruption and bribery are an established part of the business landscape. And, as a salutary reminder, there are some very big question marks over the very transaction that pushed the ROK into the top ten for the first time.

There are lessons in others’ experiences. The UK has had success with its ‘team UK’ model of deep cooperation between the government (including the armed forces) and British companies to win contracts. That can involve subsidies, offsets, or side deals and payments. But the pressure to secure deals can make what looks like a good idea at the time look less good later. Big defence deals have long tails, and have at times led to allegations of corruption and other scandals for companies and governments. Avoiding those pitfalls will require judgement of what’s in Australia’s interests, a clear and viable commercial business case, and transparency about the transactions. All that will make going up the export leader board that much harder.

Based on the volume of media coverage, the casual observer might be forgiven for thinking that Australia’s planned build-up of defence capital equipment has more to do with jobs and growth than national security. Yet, relative to the size of the investment, the amount of information available publicly on the economic impact of the proposed build-up is meagre. A number of stakeholders have recently attempted to fill a void in the availability of economic impact data, but with limited success—leaving reliable information on the industry ‘missing in action’.

Early this year, Minister for Defence Industry Christopher Pyne noted the defence industry’s contribution to Australia’s overall economic growth as measured in the National Accounts. From a 34% rise in the defence expenditure component of gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) in the December quarter 2016, the minister concluded that the industry had emerged as a ‘major reason’ for economic expansion across the economy as a whole measured by GDP.

Unfortunately, that assessment overlooks a number of important factors: the defence component of GFCF accounts for a small proportion of GDP; that component includes defence facility investment as well as the capital equipment investment normally associated with the definition of the defence (manufacturing) industry; the GFCF figure includes imported equipment; and quarterly figures are highly volatile, suggesting the appropriateness of trend data rather than the seasonally adjusted data that were used. The upshot is that the defence industry accounted for between less than 2% and 14% of the overall rise in GDP over the quarter—and the lower figure is a distinct possibility.

Defence’s naval shipbuilding plan then emerged to provide job estimates for the future submarine, future frigate, offshore patrol vessel and Pacific patrol boat projects. Covering nearly $95 billion of defence expenditure, the plan had the potential to plug a significant gap in the industry economic impact puzzle.

But the results are incomplete and inconsistent. While the economic benefits of the projects are noted, no mention is made of their potential economic costs—not even the costs associated with the government having to pay for the vessels by raising taxes, reducing expenditure elsewhere or borrowing more money. And job numbers for each project are calculated using different methodologies over different time frames, which effectively precludes them being combined to give a useful sectoral view. To what degree the results could, or should, comply with new government economic impact reporting requirements under the 2017 Commonwealth Procurement Rules is unclear.

An October report focusing on naval shipbuilding’s economic impact on South Australia added only marginally to the knowledge base. Here again the results are difficult to assess: no, more illuminating, national data are provided; economic benefits are included but economic costs are not; shipbuilding figures are combined with ship sustainment figures, making the individual contribution of building difficult to determine; and claims that shipbuilding and sustainment in South Australia will create new forms of economic activity equal to the state’s mining industry are proffered in the absence of important contextual information showing that mining accounts for only around 1% of statewide employment.

Outside the naval shipbuilding arena, an earlier economic impact report commissioned by Defence examined the effects of Australian industry’s participation in the Joint Strike Fighter global supply chain program. As the posterchild for the defence industry’s role in the development of advanced manufacturing in Australia, the program holds a position of special interest from a jobs and growth perspective.

To its credit, the study considers economic costs as well as economic benefits. However, as ASPI has already observed, the report’s estimates of economic impact are difficult to reconcile. The modelling appears to be underpinned by a somewhat unusual assumption: even after sales contracts for the JSF expire, the people those contracts help to employ can be retained, presumably as a result of the companies involved gaining enough additional capability through the JSF program to attract a completely new clientele.

State governments have over a number of years attempted to estimate what the defence industry might add to their economies. New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia have all generated relevant reports. Nonetheless, the scope of data in those documents varies enormously and not all states and territories appear to have attempted an industry profile. Moreover, the reports don’t provide all-important insights into Defence’s future procurement plans and appear to rely to at least some degree on Australian Bureau of Statistics data, which isn’t structured to reflect the special characteristics of defence manufacturing. Boeing recently commissioned an economic impact study of its activities around Australia. However, with a single-company focus, the study’s contribution to broader public policy is limited.

An outstanding feature of Defence investment in industry is that even the largest investment projects tend to have a small relative economic impact when measured on a national basis or even in terms of the economies of most states and territories. However, their effects at a regional level can be a lot more significant. Ironically, the attempts to measure economic impact noted above pay little, if any, attention to the regional dimension.

Australia’s defence industry is being exposed to the operational and technological needs of high-technology defence forces and the global prime contractors in a way they’ve never experienced before. To survive, and to flourish, Australian defence companies must understand and master the innovation process—they need to become innovators.

Australia’s defence industry is awaiting the release of two key government documents: the defence industry capability plan, which is expected next year, and the defence export strategy, which is expected by the end of this year. They’ll complement the ground-breaking Defence White Paper, Defence Industry Policy Statement and Defence Integrated Investment Program, which were released in February 2016.

Those three documents have had a profound effect: they represent the most significant change in Australia’s defence industry policy for a generation or more. They point to a destination of international industry competitiveness and prosperity, with about $1.5 billions’ worth of assistance in getting there, thanks to the Centre for Defence Industry Capability, Defence Innovation Hub and Next Generation Technology Fund.

One of the vehicles that will help Australia’s defence industry reach that destination is innovation. Why the focus on innovation? Because, as I pointed out previously, a small country trying to equip, deploy and sustain a small, high-tech defence force won’t derive either an operational advantage or an economic advantage from trying to do the same thing as everybody else, only cheaper. Innovation—in equipment, organisation and process—is the difference between being ordinary, vulnerable and irrelevant, on the one hand, and effective, strong and resilient, on the other.

However, after decades on what has often been a starvation diet, many parts of the defence industry need to get into condition to start the journey and engage fruitfully with more forward-leaning defence customers, both domestically and overseas. In a global market that leaves Australia wide open to players from around the world, Australian defence companies are being asked to compete globally, both for direct sales and for the opportunity to become supply-chain partners. To do either, they need to deliver value, to be resilient, reliable, well-run businesses.

The Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre’s recent report highlights the fundamental importance of innovation as a component of industry capability, enabling Australian manufacturing firms (which includes most of the defence industry) to compete on value and not simply on cost. To be fair, some Australian defence companies have always understood that and behaved accordingly; the rest of the industry is having to catch up.

Innovation is something new and slightly scary for defence companies reared on a diet of ‘build to print’ and tiny portions of genuine opportunity. The word itself engenders suspicion: is it a ‘buzz word’? A fashionable preoccupation? It’s certainly not universally understood within the defence industry.

For anybody who thinks the defence industry is special, by the way, I have bad news: it’s not. The defence market is special and unique, but the defence industry is like any other high-tech industrial market for capital goods and services. The good news is that the factors that make a non-defence company a successful innovator apply also to defence companies, so there’s plenty of supporting literature and no black magic involved. Of course, every project is different (some subtly, some quite significantly), but generally speaking there are common preconditions for innovation success. They reside in the intrinsic attributes and routine behaviours of the companies involved.

Once you understand that the defence industry isn’t that different, the processes, procedures and practices set out by a swag of authors who’ve studied innovation success in other sectors make sense.

A defence innovator needs technological mastery, but that’s not enough in itself. It also needs business mastery if it is to be sustainable, reliable and resilient, and therefore a trusted supplier and partner (or competitor). It needs access to the ‘smarts’ developed by others because no company, however big, can possibly be an expert in everything that it does—that means partnering with research establishments, universities and other companies (something Australian industry and academia are famously poor at doing). And it needs to engage closely with Defence—the ADF, the bureaucracy and the Defence Science and Technology Group.

Boiled down to their essentials, the preconditions for innovation success are surprisingly simple: be a technical and subject-matter expert in what you do; appoint a leader who actually wants to innovate; break down silos and allow multidisciplinary teams to flourish; invest in R&D and prototyping capabilities; look for partners whose expertise complements (or even completes) your own; and, above all, understand your market and customer intimately. (The full list is here.)

There are some defence companies that get it: not surprisingly, a few are represented on bodies like the CDIC Advisory Board. But they are far ahead of the rest of the industry on this journey. The defence industry capability plan and export strategy may provide better directions—and if they do, it’s a sign that Defence is getting it also. But industry must complete the journey itself and probably won’t make it without embracing the challenges of the innovation process.

With the federal government committed to spending 2% of GDP on defence over the next decade, Australia’s naval shipbuilding sector is set to undergo a renaissance that will drive the development of a new wave of skills and jobs, while allowing hundreds of domestic companies to tap into lucrative and sustainable global supply chains.

While some have forecast the demise of manufacturing in Australia, this commitment to building a sustainable shipbuilding industry will see supply and support facilities ramp up right around the country. It’s an opportunity for Australia to build a sustainable, world-class export industry capitalising on the government’s investment in shipbuilding.

We are living, unfortunately, in an increasingly unstable environment. Governments around the world are seeking to better equip their militaries to provide national security to their populations. Australia is well placed, as a respected middle power with solid relationships around the globe, to generate new export opportunities as it builds its own military capability.

The minister for defence industry, Christopher Pyne, has identified the Middle East as one area where Australian companies could pick up lucrative contracts.

There’s no reason not to also look closer to home, to the Asia–Pacific region where governments are seeking to build their defences amid growing regional instability. With close neighbours, such as Indonesia, the government has taken the fight to the scourge of people smuggling, successfully disrupting an evil trade. Minor war vessels have played a key role.

As well, the rate of piracy and maritime crime in Southeast Asia continues to be a concern. Maritime intelligence company Dryad, for example, in its most recent analysis posted in February 2017, reported that these activities in the waters off the southern Philippines are posing a significant threat to seafarers.

The $3 billion offshore patrol vessel program, in which Lürssen is a shortlisted bidder, provides a further opportunity for Australia to play an even stronger role in building regional capability in this crucial area.

In terms of strengthening Australia’s naval shipbuilding capacity, positive signs are already emerging. Global giant Thales has just announced plans to revitalise the Carrington Marine Services Precinct at the Port of Newcastle, creating an estimated 70 jobs in the development phase alone. This is great news for the Hunter Valley and a small but tangible sign of a growing confidence in a sustainable shipbuilding sector.

The major catalyst for this future prosperity is the federal government’s $90-billion-plus investment in new surface warships and submarines. This has generated global interest in the shipbuilding world, considering both the immediate benefits and longer term prospects in the region.

The opportunity to develop a credible, innovative and sustainable shipbuilding industry in Australia—which can eventually compete for export contracts against established incumbents such as France, Spain, Italy and South Korea—is very much in the sights of both the government and foreign shipbuilders. There’s no reason this can’t be achieved, but the scale of the challenge shouldn’t be underestimated.

The naval shipbuilding plan is an excellent starting point, but, given the scale of the undertaking, it’s time to establish guiding principles around which governments, industry and other stakeholders, such as Australia’s allies, can rally. Mistakes of the past must be recognised and avoided, along with the peaks and troughs that have contributed to shipbuilding’s so-called valley of death.

As a middle power, Australia should embrace a competitive naval shipbuilding sector that avoids a model based on having one key customer (the government) and a small oligopoly of shipbuilders. A vibrant naval shipbuilding sector must be underpinned by competition and free enterprise, and an export industry is the key to making that happen.

The Department of Defence, which is overseeing the implementation of the shipbuilding plan, must ensure that excellence and innovation in design and shipbuilding processes are promoted to demonstrate that Australia stands with the world’s best.

It will be critical to invest in shipbuilding skills, and the government has made an important start with the announcement of the Naval Shipbuilding College. The college will be headquartered in Adelaide but will provide education and training opportunities across the country. This is critical.

Australia needs to build its skills base right around the nation, not just in Adelaide and Perth, even though those cities will underpin much of the initial phase of the program. Other regional areas and cities—including Far North Queensland, Darwin, Melbourne, and regional NSW, Victoria and Tasmania—must be able to leverage the numerous opportunities that will flow through the design and build phases and then through the ongoing sustainment programs.

With most of the 12 offshore patrol vessels to be stationed at Darwin, a multimillion-dollar investment in highly skilled maintenance and other jobs will be required to support them. This will include engineering and other trades necessary to support a fleet of world-class vessels above and beyond the support that Darwin-based industry already provides. It will also offer new opportunities for Darwin-based small and medium-sized enterprises to provide a range of services with the potential to tap into global supply chains.

The opportunities are endless for Australia to work with its allies and some of the world’s leading shipbuilders and designers to develop an exciting export industry.

With careful nurturing and the right investment in skills and training, Australia can create a sustainable naval shipbuilding industry that will, in decades to come, stand as a testament to the forward thinking of this generation.

It has been a little over a year since the government released its Defence Industry Policy Statement. As well as setting a new world record for using the word ‘innovation’ in a single document, the Statement also elevated industry to the status of a fundamental input to capability. As I’ll briefly explain, I think it’s the latest attempt to square the circle that is the big-D Defence and industry relationship. I don’t think it’s doomed to failure by any means, but nor do I think it’s guaranteed to work.

And this isn’t the first time we’ve tried to do industry differently. We’ve tried baroque variations on ‘industry as FIC’ before, a recent example being Strategic Industry Capabilities and Priority Industry Capabilities. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with the idea of identifying those areas of industry that are truly critical to the delivery and support of ADF equipment. But with the PICs and SICs we made the multiple errors of identifying too many—including some that weren’t critical by any sensible measure—not putting any money where the policy’s mouth was and, in at least one high profile case, we identified a priority area and encouraged substantial local investment, before deciding that the global market could provide a solution that better met Defence’s requirements. Those sorts of experiences leave a sour taste for industry.

It’s hard to get the relationship between Defence and industry right. Defence industry policy is necessarily an exercise in balancing competing interests. I think it’s fair to say that before the latest industry statement there was a prevailing view in industry that Defence’s view was too much one of competition at all costs—even when it came at the cost of a local industry player that was expecting to get a good run because of being in a PIC or SIC business.

The First Principles review took a hard look the relationship between industry and defence and decided that it needed some work. I expect that they heard many of the same stories that Mike Kalms and I did when doing the legwork for the industry policy under David Johnston. The FPR was the origin of the ‘industry as FIC’ policy, though it didn’t explain precisely how that change would fix the relationship. And for the reasons I explained a few minutes ago, there will always be tension there—there aren’t too many losing bidders in competitive processes that stand back to reflect on the beauty of the experience.

At one level I can understand the logic of industry as FIC, because suitable industry support is clearly critical to both developing and sustaining the ADF’s capability. And I agree that the relationship between Defence and industry isn’t always as synergistic as it could be. So I think a new approach might work, but there are a couple of underdeveloped aspects that I think need further intellectual development.

First, there’s the simple observation that the new FIC isn’t like any of the others. It doesn’t belong to Defence, and it’s not an asset that the department can manage through its own internal processes. Industry has its own interests and goals, and a profit motive that requires it to look at the Commonwealth as a source of revenue. None of the other FICS are like that. With his capability manager hat on, a service chief can task his people to rewrite doctrine or change the services personnel policy. He can swing resources around to do more training if he thinks it’s needed. Defence facilities and the wider estate are managed internally, again with input from the capability managers. There’s a Logistics Command that is responsive to service needs. In other words, all of the other FICS are within the control of either a service chief or a Defence committee into which the chief has a direct input.

But a service chief can’t tell Thales or Boeing or Austal, or an SME, what their corporate priorities are—at least not in the same direct way they can direct the development of the other FICS. It’s true that Defence has some sway over industry priority setting; the $195 billion of capital investment over the next decade is certainly enough to get their attention. But that brings me to the second way in which defence industry differs from the other FICS—the party/counterparty nature of the relationship. Defence wants to spend the money for capability outcomes and protect its own interests. Industry is happy to help to deliver the capability outcomes, but what it really wants is the money.

When spending that $195 billion, it will be the duty of those in Defence signing those contracts on the behalf of the Commonwealth to do the best they can to obtain value for money for the taxpayer. That requires a degree of arm’s length to the relationship quite different to the intimacy of the relationship between the capability managers and the other FICS.

So there are some things that need to be worked out. And if it encourages some broader thinking about the ability of industry to deliver now and in the future within Defence’s capability development and acquisition processes, that’s a good thing. To give one example, if ‘industry as FIC’ means that the notion of value for money is extended beyond a narrow focus on the contract of the moment, that would likely be a good thing. Decisions on specific projects are often only locally optimal—that is, it’s the best decision for that particular purchase—but mightn’t look so flash when the whole portfolio of defence projects or the whole of life management of capability are taken into account.

A simple example is contracting for construction projects without thinking about supporting the platforms after delivery—just as is the case for the three Hobart class vessels about to be delivered. A truly smart buyer would have been thinking about ‘building for support’ a decade ago, and looking for ways to provide incentives for the builder to reduce through-life costs. The Chief of Navy certainly has an interest in making sure his new vessels are supportable, as well as driving down through-life costs. Instead, just as we did with the Collins class, we’ve built first, and thought about support later.

But let’s be clear: you don’t need to elevate industry to a FIC in order to think about it during the capability development process. The ability of the market to provide the desired capability or, conversely, the costs associated with creating an industrial base to get what we want should be part of the development of a business case for investment.

If Defence reduces ‘industry as FIC’ to a few prescribed steps in the new capability development process, I don’t think we’ll gain anything. “Sought industry input – tick!” won’t help anyone. Nor will industry expectations of getting an inside rail. What this should be all about is a respectful, mature relationship where information is exchanged (or bought and sold) when appropriate and expectations are realistic. To be honest, I don’t care how it’s badged. “Industry as a FIC” is as good as anything.

In March 2017, the Minister for Defence Industry told ABC radio that ‘We know the defence industry is driving the economy.’ He backed up that claim by referring to the just-released National Accounts for the December quarter, saying, ‘it showed that defence spending had increased by 15.2 per cent over the year and 34 per cent in that quarter alone and was showing up as a major reason for the increase in growth’.

Of course, defence spending hasn’t increased by anything like either of those figures. What’s probably happened is that one of his staff noticed the line in the ABS release that says, ‘public investment increased 7.7% during the quarter driven by Defence (34.2%) and….’.

The statisticians weren’t talking about defence spending, but rather the impact of defence investment on ‘fixed capital formation’. Checking through the ABS spreadsheets, it turns out that defence fixed capital formation for the December quarter was 15.1% higher than the corresponding figure a year before. So, almost certainly, the Minister was referring to defence fixed capital formation.

Now if you take defence-related fixed capital formation to be a proxy for Australian defence industry (I’ll explain later why it’s not) the Minister’s claim begins to make sense. Crunching the numbers, defence-related fixed capital formation contributed 0.15% to the quarterly GDP growth of 1.1%. But that doesn’t mean that defence industry was ‘a major reason for the increase in [economic] growth’. To understand why, we need to look at how GDP is calculated in the National Accounts:

GDP = Final Consumption Expenditure + Gross Fixed Capital Formation + Exports of goods and services – Imports of goods and services

Final Consumption Expenditure is the value of what’s purchased for consumption (food, clothing, medical services, etc.). Gross Fixed Capital Formation is the value asset purchases (building, railways, fighter aircraft, etc.).

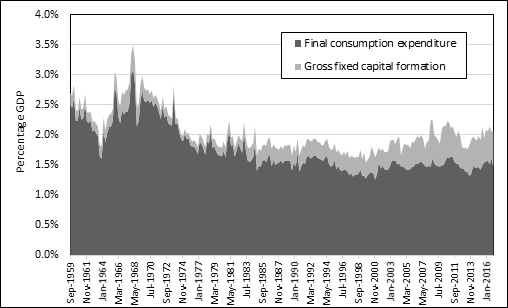

The ABS provide figures for defence final consumption and fixed capital formation (but not for exports and imports). Figure 1 shows the results going back to 1959, seasonally adjusted. Not surprisingly, the total mirrors the share of GDP spent by the government on defence. Defence final consumption is large because it includes personnel costs, as well as items such as rations, fuel, uniforms, and equipment maintenance.

Figure 1: Defence related contributions to GDP in the national accounts, 1959–2016

Note also that fixed capital formation has been growing as a share of GDP since at least the early 1970s. Fixed capital formation includes the construction of defence facilities and the purchase of new equipment. It’s been growing because (1) increases to the price of military equipment have outpaced inflation, and (2) the ADF has been becoming more capital intensive (including through the post-2000 defence build-up).

So far, no surprises: you spend a couple of percent of GDP on defence and it shows up as a couple of percent of GDP in the National Accounts. You’d worry if that weren’t the case.

But what about defence industry ‘driving the economy’. There are two problems with Minister’s statement.

First, the quarterly figures for defence fixed capital formation are too volatile to deduce anything from either a quarterly or annual quarter-to-quarter figure. The figures for the past eight quarters (working backwards) were: 34.2%, -28.6%, 30.0%, -7.4%, 32.2%, -35.3%, 29.6% and -5.1%. You can’t sensibly extract a trend from such volatile data over a brief time—it’s like looking for evidence of global warming by comparing today’s temperature with yesterday’s.

If you want to understand the economic importance of defence fixed capital, it’s the long-term share of GDP that matters. On that basis, shown in the Figure 2, there’s no short-term trend to be seen, and the long-term trend is an increase of a mere one-hundredth of a one-percent of GDP per annum.

Figure 2: Defence-related fixed capital formation as a share of GDP, 1959 to 2016

Second, as already mentioned, defence-related fixed capital formation is a poor proxy for defence industry. To start with, it includes the value of imported defence equipment (which is why the equation for GDP subtracts imports). It’s entirely possible that the 34.2% jump referred to by the Minister came from a surge in defence imports. In recent years, less than 40% of Defence’s procurement budget has been spent in Australia. Once that’s considered, the 0.5% of GDP attributed to defence fixed capital formation falls to 0.2% of GDP. And, yes, defence exports add a further boost, but it’s too small to worry about in the national accounts. In addition, defence-related fixed capital formation includes facilities construction, which is both substantial ($1.5 billion this year) and entirely unrelated to defence industry.

A focus on fixed capital formation also ignores the substantial contribution that defence industry makes to sustaining ADF capabilities. Materiel sustainment resulted in around $4 billion of local expenditure in 2015–16, compared to only $2.4 billion on equipment purchases. But the money spent on local sustainment was always going to happen, irrespective of the government’s ‘buy Australian’ defence procurement policy. The tyranny of distance means there’s usually no practical alternative to supporting defence assets locally.

To recap, far from ‘driving the economy’, defence industry contributes modestly to the national accounts. That’s to be expected; the National Accounts are roughly a case of what you put in, you get out. Moreover, the quoted growth of 34% in fixed capital formation comes from data that’s far too volatile to sensibly extract short-term trends—even if that weren’t the case, defence-related fixed capital formation is a decidedly poor proxy for defence industry.

With so much emphasis on generating jobs and growth from defence production, you’d think that the government would be getting the best economic analysis available to guide its decisions. Yet, as this example shows, that’s not the case. I wonder whether the economic analysis underpinning the looming wave of ‘nation building’ defence mega-projects is any better.

This is an extract from the forthcoming ASPI Defence Budget Brief.

I had the good fortune to be in Perth last week as a speaker at the WA Chamber of Commerce and Industry’s Defence Conference. The ‘take home’ messages of my presentation were:

One of the comments I got in the Q&A session really reminded me where I was. I was asked ‘why do you say that programs won’t be delivered? The oil and gas industry does complex projects on time and budget all the time. Just point us at it and we could make it happen’.

There was a touch of hyperbole about that, because challenging oil and gas projects certainly aren’t immune to cost and schedule problems. But there was some wisdom there as well. I visited the Australian Marine Complex during the peak of the resources boom work, and was deeply impressed by the scale of the enterprise and the expertise I found there. There was a sense of urgency I hadn’t seen at even the most professionally run defence industrial sites, which also spilled over to the onsite defence industries.

As the resources boom further recedes and resource extraction construction projects wind down, expertise and capacity is being freed up in the west. Not surprisingly, companies there are eager to apply their skills to new work in the defence sector. It’d be nice if they could bring a sense of urgency across as well.

But there’s also naivety in the wider industry sector regarding defence contracts. For better or worse, it’s not surprising that Defence is wary of letting significant contracts to players without a proven record of working for government more broadly, or defence specifically. Defence gets enough bad press (including here on The Strategist) for project underperformance, and it’s gun shy enough without taking on the additional risk of engaging contractors who don’t know the landscape. So it tends to fall back on the established players, at least as the prime contractors. It’s a variation on the old saying that ‘nobody ever got fired for buying IBM‘. (Although the ABS gave it a shot.)

But there’s a vicious circle there. The usual defence primes are so used to dealing with the ponderous mechanisms of government that they don’t push back against them. And when it comes to contract negotiation, companies are tempted to pad schedules and costs to minimise (but unfortunately not eradicate) the risk of being embarrassed by failing to deliver.

Clearly both sides need to move their world views, and to recognise the strengths and constraints of the other. Perhaps the easiest shift is on the business side of the fence. KPMG’s Mike Kalms told the Perth meeting that even the most capable firms in the wider industrial sector have to make themselves more ‘defence ready’, including learning the language of defence procurement. And, importantly, companies that have been working in the resources sector have to be able to convince government that they won’t opt out if resources prices soar again.

One way to do that is to buy into firms who already have an ‘in’ and longevity in the defence area. The impressive WA-based firm Civmec has taken that approach. They’ve already established their international competitiveness in the oil and gas sector. As an aid to moving into defence business, they recently bought the Newcastle firm Forgacs, which participated as a build partner in the air warfare destroyer project. And they used their own money to build a submarine section as a demonstration of their prowess.

It’s harder for the smaller players to get in, but some recent developments should help. New government portals provide an entry point for small-to-medium enterprises, which should help them to negotiate the sector.

But perhaps the biggest change needs to be on the government side. In order to embrace even the most capable of players from the wider industrial sector, defence acquisition and government will have to be less risk averse. That will probably mean the odd embarrassment down the track—but it’s not like that doesn’t happen anyway.

The unprecedented focus on Australia’s defence industry during the current federal election campaign has highlighted the role the industry can play in developing sovereign capability and industrial self-reliance in key areas of defence procurement.

In equal measure defence industry is now being recognised as a valuable contributor to both jobs and capability.

The Defence Industry Policy Statement which accompanied the Defence White Paper stated that, for the first time, the Government has formally recognised the vital role of Australian defence industry as a discrete, fundamental input to capability. The Defence organisation will now fully consider both industrial capabilities and the capacity of Australian businesses to deliver to Defence.

This formal recognition has been welcomed across industry as has the acknowledgement that a formal framework is required to identify and manage those sovereign industrial capabilities to be maintained and supported by Defence.

The new arrangements will be closely monitored by industry and it would appear that the first test for the new approach will be for the selection of a combat system integrator for the future submarine.

Under the old regime support of the Collins-class submarine combat system was deemed to have been a priority industry capability. Whether an analogous arrangement will be secured for the integration and sustainment on the same AN/BYG-1 combat system on the RAN’s future submarine will depend very much on this important selection.

Strong guidance for this decision was provided in the Future Submarine Industry Skills Plan produced by the Department of Defence in 2013.

Amongst other things, the report measured the strength of Australia’s combat system workforce and found that considerable experience and skill resided in the people who commenced the Air Warfare Destroyer combat system integration task in 2005—the same core team that had previously worked on the Collins replacement combat system. Importantly, it stated:

‘The benefit of having an established proven team is much greater than generating a new team of experienced people. The team comes with people who know each other—teamwork and proven tools and processes.’

The report noted that, had the AWD task been undertaken by a newly formed team, ‘it would have required more time and budget because of low productivity and time spent by the team working out roles and dependencies.’ For the purposes of the future submarine the report made the strong conclusion that it takes time to grow individual skills and more time to grow proficient teams.

It’s no coincidence that one team for the future submarine integration role offers not only the largest combat system workforce in Australia and the promise of 700 Australian jobs, but nominated key personnel with more than 150 combined years of in-country Australian submarine combat system integration experience. By any measure this represents the basis for a sovereign submarine combat system integration capability for Australia.

After making such a strong statement about the importance of blue collar jobs to the city of Adelaide it would be incongruous to rely on a fly-in fly-out workforce to provide the sovereign, high end systems integration roles Australia requires.

The forthcoming decision on the combat system integrator for the future submarine therefore offers a genuine opportunity for Defence to demonstrate the strength of its commitment to a truly sovereign Australian defence industry.

I’ve been trying to understand the government’s policy on defence industry. Having read the recent Defence Industry Policy Statement (DIPS) it seemed straightforward, but then I looked closely at the Prime Minister’s recent announcement about submarines. Unless I’m missing something, it looks like we have a fundamentally new policy even as the ink dries on the old one.

I’ve been trying to understand the government’s policy on defence industry. Having read the recent Defence Industry Policy Statement (DIPS) it seemed straightforward, but then I looked closely at the Prime Minister’s recent announcement about submarines. Unless I’m missing something, it looks like we have a fundamentally new policy even as the ink dries on the old one.

The 2016 DIPS is an unsurprising document. Like most government glossies, it talks up its big-ticket ‘announcables’. Specifically, $1.6 billion over ten years to establish:

The first two initiatives will be funded entirely by redirecting $870 million from existing programs. While there’s some relabelling afoot, the joint defence industry CDIC is a new concept. The remaining $730 million for the technology fund will come from Defence’s investment program. On the scale of defence spending, $73 million a year is a significant but not over-the-top investment in new technology.

So much for feeding the technology chickens; there are two other aspects to defence industry policy that are much more important. The first is ensuring that the ADF has access to the industry capabilities it needs. To this end, the existing Priority and Strategic Industry Capability framework will be replaced by a Sovereign Industrial Capability Assessment Framework ‘to improve the identification and management of the sovereign industrial capabilities that develop and support our ADF capabilities’. In addition, industry has been recognised as a Fundamental Input to Capability with the goal of driving ‘more formal consideration of industry impacts through the early stages of the capability development life cycle’. Responsibility for doing so will fall on the Capability Managers (a.k.a the service chiefs and the Vice Chief of the Defence Force) who will be assisted by the CDIC.

The test of this new approach will come with the new Defence Industrial Capability Plan, promised for 2017, with sovereign industrial capabilities identified through a ‘collaborative process between Defence and the CDIC’. Past attempts to identify key defence industry capabilities have succumbed to special pleading by incumbents in a case of ‘we have to do what we do because it’s what we do’. The stronger role of industry in the new process can only increase the influence of existing firms.

The other critical question for defence industry policy is how much preference will be given to local suppliers. In the 1980s and 90s we had explicit programs, such as the Australian Industry Involvement scheme, that favoured local suppliers irrespective of cost. More recently, however, governments have taken a more economically rational approach that saw equipment purchased off-the-shelf from overseas while creating opportunities for local firms to bid competitively into global supply chains.

The new DIPS maintains the existing overarching approach to defence procurement. That is, apart from sovereign requirements, decisions will ‘seek to achieve the best value for money’ with consideration of ‘opportunities to maximise internationally competitive Australian industry involvement’.

Thus, in terms of what matters, the new DIPS reflects continuity. There’s no changed preference for local suppliers, and the arrangements for managing sovereign industry capabilities aren’t markedly different to the old ones for priority/strategic industry capabilities. If there has been a noteworthy change, it’s probably the extra $73 million a year to invest in ‘game-changing technologies’.

But defence industry policy is a slippery beast. It’s always possible to hide a preference for local suppliers behind a fig leaf of preserving sovereign capability. Moreover, if firms bidding for defence contracts think there’s an advantage in offering high local content, they’ll happily do so and pass on the costs. For these reasons, the government’s actual procurement decisions, and how it explains those decisions, are every bit as important as its declared policy. Which brings us to the submarine announcement.

When asked about local content in the submarine program, the Prime minister said:

‘I am determined that every dollar we spend on defence procurement as far as possible should be spent in Australia, and our commitment to that is precisely for the reasons that Marise and I and Christopher and the Vice-Admiral have spoken about. Because when we invest in Australian industry and jobs, Australian technology, we are strengthening our whole economy.’

Apart from expressing an unqualified preference for local suppliers in stark contradiction to the DIPS, the Prime Minister stressed the economic benefits of doing so. It wasn’t an isolated mention; the same point is made at three other points during the announcement. Yet, the DIPS says absolutely nothing—not a single mention—about using defence procurement to build a stronger economy.

It’s not that there’s an iron-clad strategic argument for building submarines in Australia, otherwise the government wouldn’t have asked for offshore and hybrid options from the contenders. Rather, a judgement has been made that the cost premium for local production, which the government concedes exists, is outweighed by economic and other benefits. That might be the case, but it’s not reassuring that the government refuses to disclose the cost premium or to release the economic impact report it commissioned on the submarines (at a cost of $387,000). If it’s such a good deal, why are we being kept in the dark?

There’s no denying that there were political factors behind the submarine decision, but that doesn’t mean that there hasn’t been an important change in policy; it merely explains why. Mindful of what the Prime Minister said in Adelaide, future bidders for defence contracts will be packing in as much local content as they can, with the risks borne by the ADF and the costs by taxpayers.

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria