Australia must accelerate development of defence technology to deter war

Many people rejected the very idea of building a modern defence technology company when I founded Anduril Industries in 2017. They thought the international rivalries and confrontations of the past had faded with the end of the Cold War and modern conflict would remain a limited affair. It was almost unfathomable in a time when a ‘rules-based order’ promised eventual prosperity for all that a major war between great powers could occur in such an interconnected global economy.

Such wishful thinking has yielded to the harsh reality of the present. A year after Moscow began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Ukrainian people continue to fight bravely for survival in a war that has killed and wounded hundreds of thousands, with no end in sight. The West has flooded Ukraine with arms and equipment. And in the small Ukrainian city of Bakhmut we have witnessed savage trench warfare not seen since World War I.

Meanwhile, in the Indo-Pacific, aggressive Chinese military exercises and missile launches over Taiwan have become the ‘new normal’. North Korea recently threatened to use waters near South Korea and Japan as its ‘shooting range’. And China’s use of economic blackmail and threatening posture towards Australia and other neighbours have heightened fears in the region of a future conflict.

This dangerous world is why Anduril exists: because the West must have critical tools to preserve our way of life, uphold the values of free and fair societies and deter powerful adversaries from dominating weaker nations.

You can’t credibly deter war without superior technology. If the Ukrainians had an arsenal of technologically sophisticated weaponry from the start, if they were a prickly porcupine that nobody wanted to cross, then this conflict likely never would have started.

America’s tech industry has catapulted forward, while our defence industrial base, which once produced technology beyond what we imagined in science fiction, has largely stopped innovating. There’s more artificial intelligence in a Tesla electric car than in any US military vehicle and better computer vision in your Snapchat app than in any system the Department of Defense owns.

Tomorrow’s weapons—autonomous systems, cyber weapons and defences, networked systems and more—are enabled through software. And the talented software engineers who can build faster than our adversaries reside in the commercial tech sector, not in defence industry.

China and Russia are determinedly seeking asymmetric advantage using technologies developed for the consumer and business sectors and applying them to their military projects. They’ve been spending their resources on, for example, cheap autonomous systems that are uniquely suited to go up against exquisite weapons that cost an enormous amount of money per shot.

Anduril recognises the important role Australia plays in the Indo-Pacific. As an island continent with a relatively small population, Australia faces unique security challenges—primarily its need to defend a vast coastline and maritime border from adversaries. Fortunately, advanced technologies like autonomous systems, sensor fusion, computer vision and artificial intelligence can provide Australian soldiers, sailors and aviators with asymmetric capabilities to help them do more with less.

As retired Australian Army major general Mick Ryan says, such technologies ‘are too cheap, too available and too capable for military and other national security institutions to ignore’. And this new tech will increasingly take on the dull, dirty and dangerous jobs, so that warfighters can operate safely out of harm’s way, understand their surroundings and focus on making critical decisions.

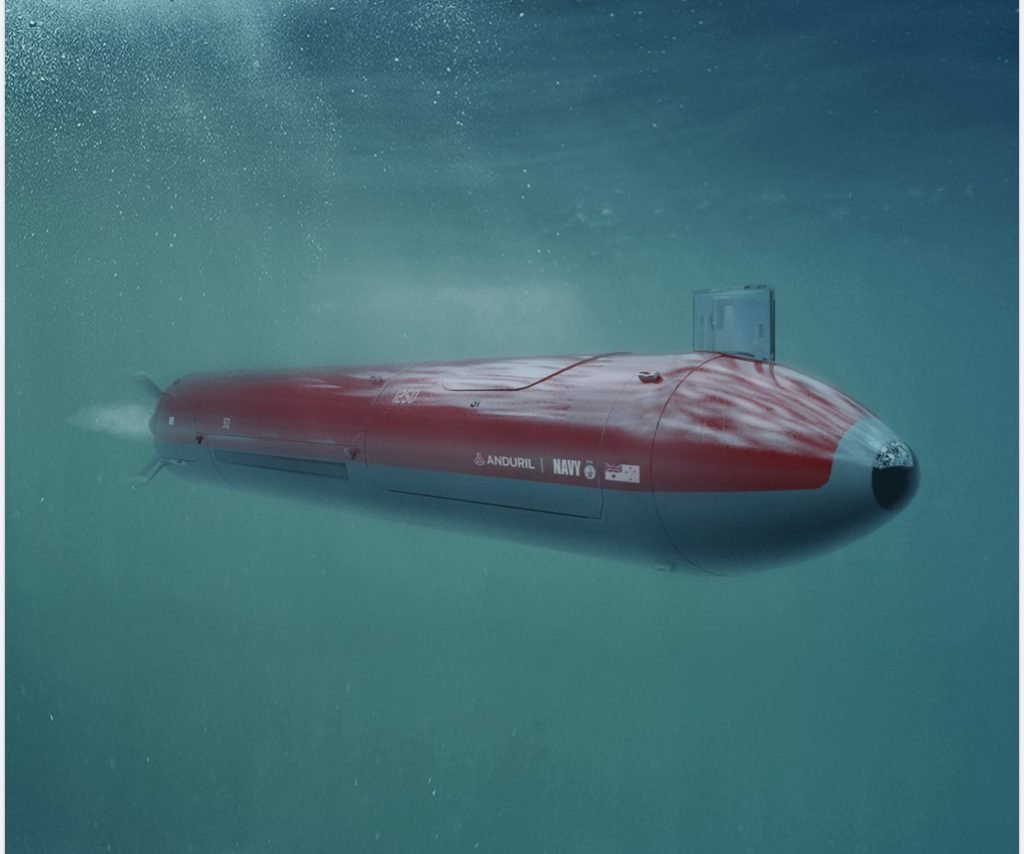

In December, my company partnered with the Royal Australian Navy and the Defence Science and Technology Group to build extra-large autonomous underwater vehicles to survey and protect Australia’s vast coastline. These Ghost Shark submarines are designed to scout and patrol waterways without risking human life. Australia will be able to see what’s hiding beneath the waves along its massive maritime border, autonomously monitoring the seas while making it harder for the submarines of any adversary to operate there.

This is the kind of smart tech that can deter war. But such capabilities are only developed by investing in military technology to remain competitive, provide an effective deterrent and prevent conflict.

Unfortunately, there’s no secret government silo of advanced technology to save us if war breaks out. If the allied democracies are to prevail, we will need action at scale. The only way we’re going to end up with a silo of advanced technologies is if we build it—and not just Anduril. We need dozens of new innovative companies and tens of thousands of new engineers who uphold the values of a free and fair society to modernise our military.

Fortunately, there’s still time, and so many in Australia, the US and elsewhere are committed to securing a future that is safe, prosperous and free. That future will be assured so long as our military personnel are provided with advanced technology today to face the challenges of tomorrow’s battlefield.