Budgeting for Australia’s nuclear-powered submarines

The upper estimate of $368 billion for Australia’s acquisition of eight nuclear-powered submarines is an impossibly large number. Stacked in $100 bills, each 0.14 millimetre thick, the pile would rise to about 500 kilometres. You could build 1,000 40-storey buildings in Sydney, buy every single house and apartment in Adelaide, or make a gift of $40,000 to every household in the country.

The figure is more conjectural than realistic. It’s what you get when you estimate that the program will add about 0.15% of GDP to defence spending over a 30-year period. As the Australian Financial Review’s Phil Coorey noted, the National Disability Insurance Scheme will cost $2 trillion over the same time.

With GDP currently around $2,000 billion a year, a 0.15% increase would be equivalent to around $3 billion a year, adding roughly 8% to the defence budget.

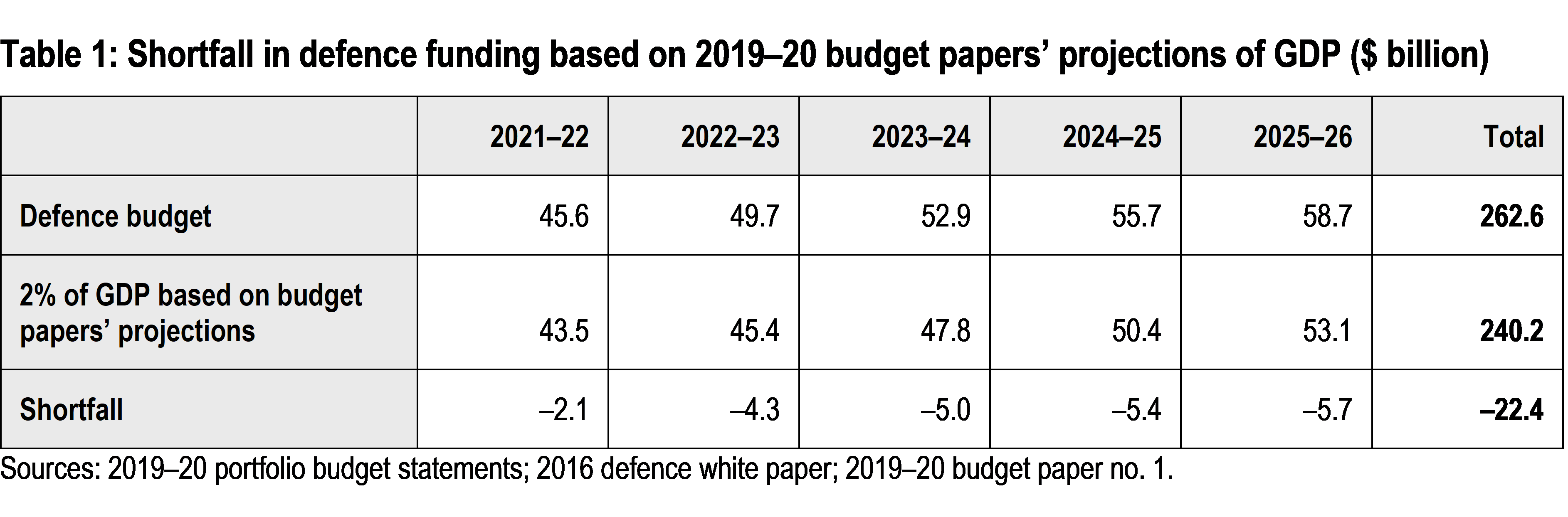

That sounds less scary. Defence Minister Richard Marles has endeavoured to make it sound even more benign, noting that around half the sum required over the next decade has already been allocated in the budget to pay for the now-cancelled French submarines and suggesting it won’t really cost taxpayers anything over the next four years.

Two-thirds of the $9 billion cost in that period is offset against savings from not buying the French submarines, and the $3 billion balance is to be absorbed elsewhere in the defence budget.

Although the early phases of the project are relatively clear, with $2.5 billion to be given to the United States to upgrade its shipyard and another $2 billion to upgrade the Adelaide submarine yard, the cost of designing and building new nuclear submarines from scratch in collaboration with the United Kingdom is beyond any realistic reckoning. It could be 0.15% of GDP or a multiple of that. It is unlikely to be less. The timing of that spending is similarly beyond calculation.

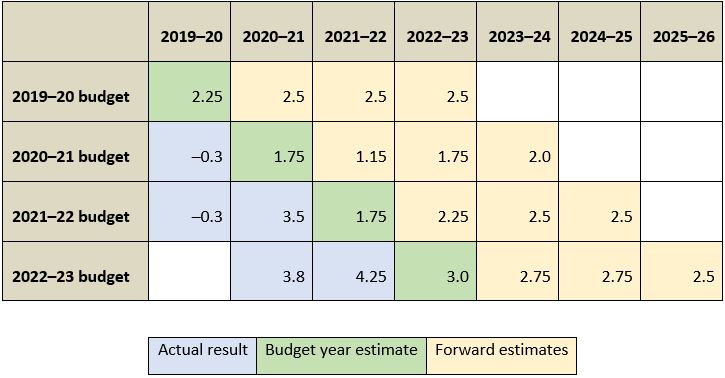

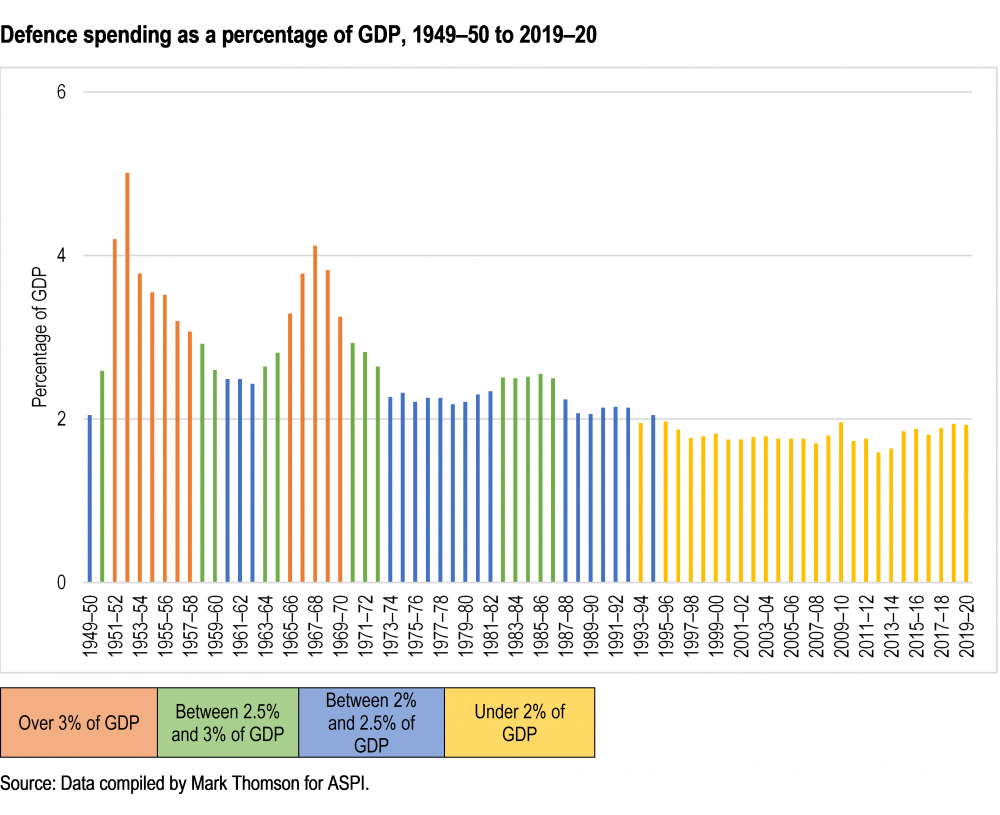

Marles commented that the investment in submarines was part of a build-up in defence spending from 2% of GDP to 2.2%. The 2020 defence strategic update noted that defence spending was no longer linked to GDP, to avoid having to adjust it whenever the pace of economic growth changed. However, the measure remains a useful benchmark both to compare defence with other calls on the public purse and to assess international relativities.

When the defence budget was cut by $5 billion in 2012 in a vain effort to return the federal budget to surplus after the global financial crisis, it was noted that defence spending had dropped to 1.56% of GDP, the lowest level since 1938. Australia had a substantial overseas military commitment at the time in Afghanistan, but the war on terror was essentially ‘low tech’.

Geopolitics has become a lot more complex since then.

China has emerged as an assertive global power, intensifying a rivalry with the United States. North Korea has become a capable nuclear power and efforts to prevent Iran from a similar achievement have faltered. In the wake of its invasion of the Ukraine, Russia now defines the US, and by extension the West, as an ‘existential threat’.

Without entering a debate over whether nuclear submarines are the best response to this more menacing world, it’s easy to see why successive governments have decided a higher level of defence spending is warranted. The question remains whether Australia can afford it.

The state of federal finances will be updated in next month’s budget, but the new Labor government’s first budget, released last October, painted a sombre picture of the outlook, with slowing world and domestic growth as global economies wrestled with spiralling energy prices and inflation. The previous government had anticipated paring away the budget deficit and bringing net debt back to zero before the end of the decade, but the October update saw the deficit stuck at 2% of GDP for years to come and debt continuing to climb.

Only 10 of the 36 advanced nations in the International Monetary Fund’s latest budget survey are running budget surpluses, and the average deficit is about twice the size of Australia’s. However, Australia has an unusual vulnerability. For most countries, the prices fetched by their exports and paid for their imports are fairly stable. In inflationary times like now, both are rising, but the relativity between the cost of imports and the earnings from exports doesn’t change a great deal from one year to the next.

Australia’s exports, by contrast, are subject to the wild swings of commodity markets, while imports are overwhelmingly manufactured goods with unit costs under downward pressure as the economies of scale improve. The relationship between export and import prices (known as the terms of trade) matters for the federal budget because roughly a third of the income from exports flows to the government in tax revenue.

Australia’s terms of trade have enjoyed an almost 20-year boom, thanks to the rapid development of China. The terms of trade is measured as an index, and for most of the previous 50 years to 2005, it averaged around 60 points, rarely deviating by more than plus or minus 10 points. However, it now sits at 110 points, almost double the historical average. That translates into roughly a $275 billion a year boost to the national economy, with $90 billion flowing to the federal budget.

Until the early 2000s, it was thought that Australia’s terms of trade were in a slow but long-term decline. The thinking was that economies would increasingly value high technology, while the steady improvement in economies of scale in the resources sector would bring a reduction in costs.

Instead, the China boom has elevated Australia close to the top of world rankings of living standards. It costs the big miners less than US$20 a tonne to dig up the iron ore that they have lately been selling to China for US$125. It can be argued that Australia’s investment in nuclear submarines is being financed by China.

There’s data for Australia’s terms of trade going back 150 years, and historically, booms have always been followed by busts. The danger for Australia and its plan to acquire nuclear submarines is that the premium for Australia’s exports disappears.

A global recession would do it, but so too would a move by China to a slower, less infrastructure-intensive growth path. Without the China premium on our exports, a budget deficit of 2% of GDP could blow out to three or four times that. With credit-rating downgrades, there would be pressure from global financial markets for the government to slash spending wherever it could, including defence.

The alternative would be to raise taxes. Among advanced nations, Australia is one of the lowest taxing countries; only the US, South Korea and Switzerland raise less as a share of GDP. Australia’s taxes raise 27% of GDP, compared to an advanced nation average of 32% and France at 45%.

Defence is not the only sector requiring more federal funding, with ever-increasing demands for social spending, industry support and infrastructure. The time to be raising taxes to strengthen the budget is before a crisis strikes—preferably now.

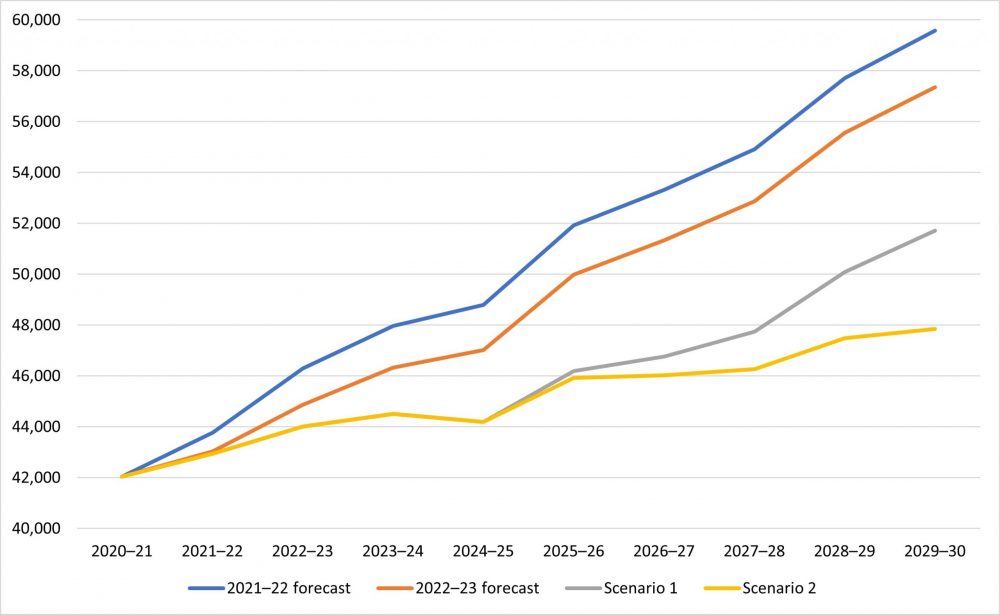

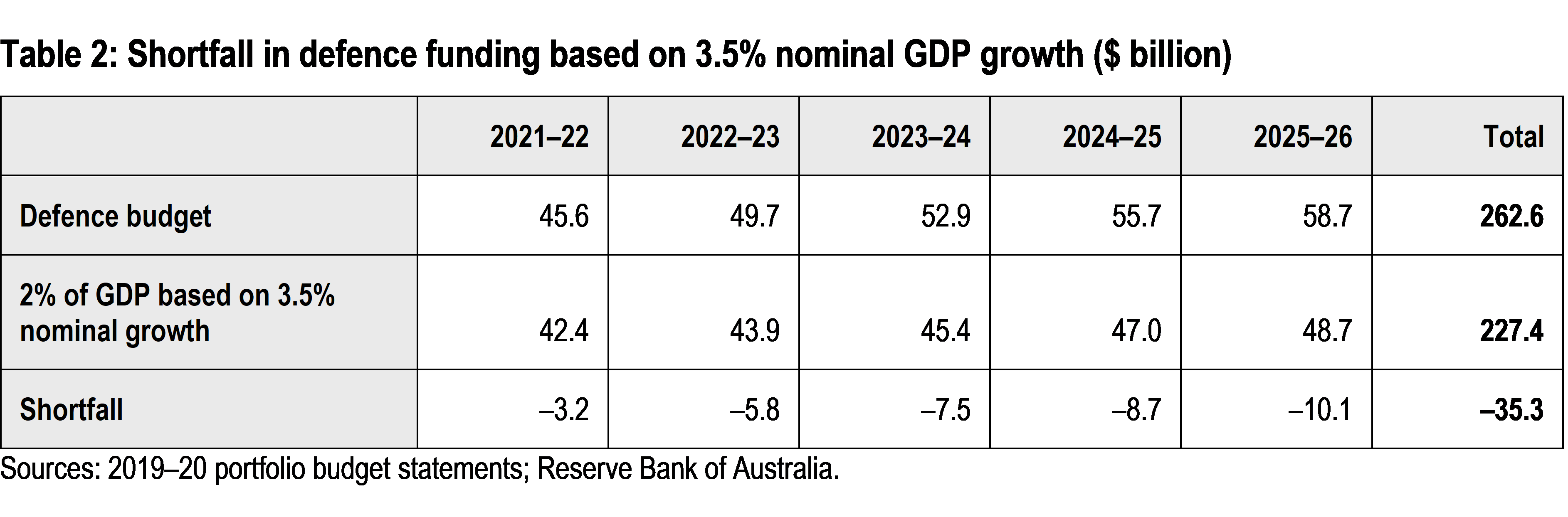

That sort of projection is probably a worst-case scenario (hopefully). But short of economic miracles, the white paper’s fixed funding line is going to substantially exceed any 2% of GDP line. For them to align, average annual nominal GDP growth of around 5.5% would be needed, a much better result than Australia has managed over the past decade. In light of the copious analysis that suggests GDP growth is being driven largely by immigration rather than by enhanced productivity, sustained nominal growth of 5.5% seems unlikely.

That sort of projection is probably a worst-case scenario (hopefully). But short of economic miracles, the white paper’s fixed funding line is going to substantially exceed any 2% of GDP line. For them to align, average annual nominal GDP growth of around 5.5% would be needed, a much better result than Australia has managed over the past decade. In light of the copious analysis that suggests GDP growth is being driven largely by immigration rather than by enhanced productivity, sustained nominal growth of 5.5% seems unlikely.