Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

When the US Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman Mark Milley announced, ‘We’re at war with Covid-19, we’re at war with terrorists, and we’re at war with drug cartels’, he articulated a fear shared by many who watch illicit non-state actors. Transnational organised crime and terrorist groups have a crucial thing in common: their business models are built around exploiting governance dysfunction and vulnerabilities. It’s inevitable that they’d seek to capitalise on the strain the Covid-19 pandemic is placing on state institutions and a potential emerging security gap.

In Asia, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime is struggling to bring the region’s law enforcement agencies together to share information and intelligence and to plan and conduct joint operations. Face-to-face meetings of intelligence officials have been indefinitely postponed, public security ministers and senior officials are in lockdown, and frontline law enforcement, border and customs officials are being tasked with the impossible. The pandemic is exposing fatal flaws in the capacity and response of the public security sector.

Transnational organised crime syndicates and terrorist groups are also having to rethink and adapt in response to the challenges and opportunities posed by the pandemic. From a cyber and crime–terror nexus lens, two dynamics are evident: there’s likely to be greater convergence between organised crime syndicates and terrorist groups, and that will lead to greater access to and activities in the cyber domain by both criminal and terrorist organisations.

The recent upsurge in cyberattacks against organisations and individuals is significant. That activity is expected to increase as perpetrators use the Covid-19 crisis to carry out attacks themed around the virus by distributing malware packages. Interpol has issued a warning to organisations at the forefront of the global response to the outbreak that have also become targets of ransomware attacks.

Cybercriminals are likely to exploit an increasing number of attack vectors as employers institute telework arrangements and allow remote access to their organisations’ systems and networks. Interpol warns that frontline hospitals, medical centres and public institutions are being targeted by cybercriminals.

Terrorist organisations will also try to take this opportunity to further their objectives. The latest issue of the Islamic State’s al-Naba newsletter says that the security ‘distraction’ of countries trying to control and respond to the spread of Covid-19 leaves an opening for jihadists to exploit. The US Department of Homeland Security has warned that ‘extremist groups are encouraging one another to spread the virus … to targeted groups through bodily fluids and personal interactions’.

Agencies tasked with combating these threats must recognise the crime–terror nexus as a key dynamic. Organised crime and terrorist groups often operate along a continuum of degrees of convergence that are agnostic to the groups’ differing objectives. Terrorists’ pursuit of ideological, political or religious aims can be synchronistic with transnational organised crime’s pursuit of profit and other material benefits. Essentially, the commonality is the facilitation of goods and services. But it can also lead to hybrid organisations such as Abu Sayyaf in the Southern Philippines and the FARC in Colombia.

For non-state actors who naturally operate in the shadows of states, the cyber domain offers refuge.

Both organised crime and terrorist groups are recruiting from new demographics. Terrorist organisations, as they increase in popularity, diversify their human capital needs and acquire members with advanced training and expertise, enabling these groups to operate in new areas.

The cyber domain—to which social media is the gateway—has significant appeal as a battlefield to the millennial jihadist. This makes terrorist groups more agile and more adaptive and therefore harder to disrupt. In the past, groups such as al-Qaeda and IS used the internet mainly to recruit young jihadists and promote their beliefs.

Terrorist groups now tend to have in-house cyber expertise and can branch out into actual cyber terrorism. And, importantly, groups that don’t have the capabilities can gain access to these services through client–patron relationships with organised crime syndicates.

As countries continue to close their borders (and keep them closed) due to Covid-19 and the movement of goods and people becomes increasingly restricted, transnational organised crime and terrorist groups will likely increase their reliance on commercially based relationships and hybrid tactics. They will look for new zones of exploitation, and that will include the cyber domain.

The crime–terror lens offers insights into both the services and the access to capabilities that organised crime provides to terrorists. This includes the services cybercriminals provide to facilitate illicit activities by terrorist groups in the cyber domain—which is distinct from cyberterrorism.

The crime–terror nexus has changed the way in which these cybercriminals operate. They use methods that increase the effectiveness of terrorist operations and logistics. For example, operational capabilities of terrorist organisations are enhanced through transnational organised crime syndicates acting as facilitators and providers of services. In the cyber domain, it can include cyber criminals providing hacking capabilities or supplying malware packages to disrupt targeted states, facilitate operations or launder and move funds. Organised crime networks have also used information and communications technology to facilitate various forms of traditionally offline activities, such as trafficking of people and ordnance of interest to terrorist groups.

As governments, international organisations, civil society, and the public and private sectors scramble to respond to the pandemic, there’s a risk that their usual policies and practices to curb organised crime will be weakened or become outdated. This has significant implications for the fight against both organised crime and terrorism. One key to success lies in understanding the nexus between the two.

The cyber domain presents new opportunities for convergence. Policing the digital world will therefore become increasingly important and increasingly difficult. The Covid-19 pandemic demands new mediums and modes of engagement. Illicit non-state actors operating in grey zones are potentially well placed to take advantage of the pandemic and turn risk into revenue.

The Covid-19 pandemic has sent the world into perilous, uncharted territory from which no country will emerge unscathed. More than half of the global population is under some form of lockdown. All economies, rich and poor, are falling into recession and can limit the fallout only by working together.

China—the pandemic’s first epicentre—offers insight into the need to work together. The months-long lockdown of Hubei province, together with strict movement restrictions across the country, caused a nearly 40% drop in year-on-year industrial profits in January and February. Factories began to reopen in March, but have faced order cancellations, postponements and payment delays as overseas buyers struggle to cope with the pandemic’s effects.

So, even as public health is recovering, the speed of China’s economic recovery will depend at least partly on the rest of the world. Given how deeply interconnected the global economy is, this will be true for every country: even as the pandemic is controlled at home, disruptions elsewhere in the world—and, potentially, additional waves of outbreaks—will impede recovery.

Global supply chains tell a similar story. Even before the pandemic, supply chains were absorbing the impact of two years of trade disputes between China and the United States. Now, they’re dealing with a combination of production stoppages, transportation disruptions and plummeting global demand. The World Trade Organization estimates that global trade may fall by as much as 32% this year. Meanwhile, unemployment is skyrocketing in many economies: in the past five weeks, a record 26.4 million unemployment claims have been filed in the US alone.

It is high time we recognised how irrevocably connected and interdependent the world has become. No country can win on its own, despite what some may think. As the world confronts a severe recession and humanitarian catastrophe, nationalist political posturing is the last thing anyone needs.

The only way to minimise the pandemic’s fallout is with solidarity: to protect their own people, national governments must collaborate to develop solutions that benefit all people. The first step is to remove protectionist tariffs and other trade barriers, thereby ensuring that critical goods—especially medical supplies and equipment, and food and other essentials—are delivered wherever they are needed. Nobody is safe until everybody is safe.

Solidarity also means protecting jobs, incomes and livelihoods everywhere. Among other things, this demands practical measures to keep small and medium-sized enterprises afloat—a point that the International Chamber of Commerce recently underscored. SMEs account for a significant share of jobs in most major economies and provide many of the goods and services we use daily. To ensure that a general slowdown doesn’t cause lasting structural damage, these firms must be protected.

But the imperative extends beyond propping up existing firms long enough to return to business as usual. As we chart a pathway out of the Covid-19 crisis, we should aim to create a better future, shaped not by competition, with countries weaponising the trade and other ties that underpin shared prosperity, but by mutually beneficial cooperation.

As we work to revitalise multilateralism, we must also reshape it in a way that recognises and reflects the many dimensions of global interdependency. This means, first and foremost, ensuring open and sustainable global trade, which is a proven means of enabling all countries—large and small, rich and poor—to achieve economic growth and alleviate poverty. Trade also underpins global peace and stability, by giving everyone a stake in the same world system.

Establishing such a system requires more than removing the tariffs, administrative impediments and ‘behind the border’ measures that encumber the movement of basic consumer products, industrial goods, and especially technology. Countries must recognise that either we all win—with people everywhere gaining access to the tools they need to improve their quality of life, develop industries and innovate—or we are all worse off.

That means drastically improving access to trade finance, especially in the emerging economies, where there’s a funding gap of over US$1 trillion. Insufficient trade and investment finance hits SMEs especially hard, hampering their ability to expand or innovate in good times and to survive in bad times. That’s why the International Chamber of Commerce has called on banks to boost bridge funding to companies to mitigate the worst effects of the Covid-19 crisis, and allow companies to continue to trade through a financial shortfall.

But much more needs to be done. While boosting trade finance during the 2008 global financial crisis helped to catalyse the global recovery, progress has since stalled. To ensure a sustained recovery from this crisis, and the development of a more resilient and inclusive global economy in the longer term, trade finance must occupy a permanent place on the global agenda.

Reviving multilateralism and ensuring open trade are entirely achievable objectives. They require no new laws or additional resources, only commitment and solidarity. The payoff—equitable and sustainable development—would be massive.

Humanitarian aid has long proved critical in times of crisis. Now, in the midst of a crisis gripping the entire world, all of us must recognise the importance of humanitarian trade.

Australia has so far managed the Covid-19 pandemic as well as anywhere else on the planet, except perhaps our near neighbour New Zealand or the vibrant techno-democracy of Taiwan.

That’s lucky, because if our federal, state and territory governments and our population had not cooperated on the drastic social-distancing measures put in place in the past few weeks, the horrific scenes we’ve seen in New York would be happening right now in Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth and Brisbane.

In that alternative universe that we were just a few days and decisions away from, we wouldn’t be hearing restive Australians asking what all the fuss is about. We’d all be angry and energised about the lack of protective equipment and ventilators in our overwhelmed hospitals and we’d all be asking why our governments and our companies couldn’t supply us with what we urgently needed.

That alternative future we have so far narrowly avoided has a close connection to our $40 billion per annum defence organisation, because the Department of Defence and the Australian Defence Force have some eerily similar needs for rapid development and production of technology.

So, defence is also the organisation that we should be able to turn to for rapid development and production of systems—whether ventilators or other equipment—in future crises, military or otherwise. That’s the advantage organisations with big budgets and high technology needs have, if orchestrated and organised properly.

It’s not news to anyone involved in defence policy and capability that the rapid change in civil technology is also affecting the balance of advantage between the world’s militaries. For Australia and our allies, there’s a lot of bad news here about Chinese, Russian, Iranian and even North Korean militaries’ and intelligence services’ rapid development and adoption of technologies. Terrorist organisations like Islamic State (no, they’re not dead, not even resting) are also skilled at rapidly making and fielding very dangerous systems—improvised explosive devices, armed drones and even cyber systems.

Depressingly, our defence organisation, like numerous Western militaries, is struggling to cope with the pace of change. Instead, it has doubled down on its long lead time approach to developing and acquiring military equipment, which is why we see the bulk of the government’s $200 billion integrated investment program for defence going into ships, submarines and big armoured vehicles that are taking years—decades, in the case of the ships and future submarines—to design, build and get into service.

Even if these lumbering capability programs are still useful when they eventually turn up, they won’t succeed alone. The big manned subs will need to work with legions of small unmanned, disposable systems that can inform and protect them against enemy ‘kill webs’ of manned and unmanned systems. The same is true for the air force’s joint strike fighters, the navy’s future frigates and the army’s big armoured vehicles.

So, our defence organisation will need to do two things. Operationally, Defence and the ADF need to be able to respond to technological and tactical surprises, like when an adversary unexpectedly fields a new and highly destructive weapon such as a directed energy gun, or uses a biotech weapon that ‘out-stealths’ the most advanced system in Australia’s or America’s arsenal. And, to do so, they must be able to out-innovate adversaries. That’s done by developing and fielding new weapons and protective systems very fast, whether they are countermeasures that protect against the adversary’s weapons or even more powerful or effective weapons that overturn the adversary’s advantage.

The ADF has done this before as a one-off, crisis-driven exercise. That story is told in Brendan Nicholson’s history of the Bushmaster protected mobility vehicle and the counter-IED systems used with it during Australia’s part in the Afghanistan war. So, it’s possible.

But Defence needs to get beyond one-off, ad hoc solutions for this abiding technological problem. That can only be done by creating a focal point in Defence that has this as its primary task.

A seed for this approach is Defence Minister Linda Reynold’s announcement that Chief Defence Scientist Tanya Monro is heading up a new Defence-led rapid response group. Its task is to ‘help increase domestic stocks of invasive ventilators, as part of Australia’s response to the Covid-19 outbreak’. It will do this by coordinating ‘the activities between public and private stakeholders, … harnessing Defence Science and Technology’s capabilities and facilities, and utilising existing expertise in specialist research engineering and technology development’.

There’s a deep irony here, though: the government is creating this group because Defence has the latent capacity to do this urgent work well by using its own scientific and engineering expertise, and by taking advantage of partners it already has in academia and industry. But it has no standing arrangement or dedicated section that takes advantage of these latent strengths and applies them to meet the ADF’s own already obvious and urgent military needs.

The new group will undoubtedly do fantastic work. The obvious question, however, is why such a group wasn’t already part of Defence’s permanent structure. If it had been, not only would the ADF be able to keep up with and outpace potential adversaries’ capability development, but Defence would also not need to stand up an ad hoc group in a time of crisis. We would be weeks ahead on the ventilator challenge by now.

May Monro succeed beyond her and Reynolds’s wildest expectations. And may this lead to Defence doing what the future military operational environment, and our current pandemic, require: creating and operating a permanent, well-resourced rapid response group. That will mean that in future times of military conflict, or grave national crisis like we have now, Australia will be able to rapidly develop, manufacture and operate machines and systems we need urgently in numbers. This is only going to be more necessary in our turbulent future.

The Covid-19 pandemic, much like a major war, is a defining moment for the world—one that demands major reforms of international institutions. The World Health Organization, whose credibility has taken a severe beating, is a good place to start.

The WHO is the only institution that can provide global health leadership. But, at a time when such leadership is urgently needed, the body has failed miserably. Before belatedly declaring the Covid-19 outbreak a pandemic on 11 March, the WHO provided conflicting and confusing guidance. More damaging, it helped China, where the crisis originated, cover its tracks.

It is now widely recognised that China’s political culture of secrecy helped to turn a local viral outbreak into the greatest global disaster of our time. Far from sounding the alarm when the new coronavirus was detected in Wuhan, the Chinese Communist Party concealed the outbreak, allowing it to spread far and wide. Months later, China continues to sow doubt about the pandemic’s origins and withhold potentially life-saving data.

The WHO has been complicit in this deception. Instead of attempting independently to verify Chinese claims, it took them at face value—and disseminated them to the world.

In mid-January, the WHO tweeted that investigations by Chinese authorities had found no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission of the virus. Taiwan’s 31 December warning that such transmission was likely happening in Wuhan was ignored by the WHO, even though the information had been enough to convince the Taiwanese authorities—which may have better intelligence on China than anyone else—to institute preventive measures at home before any other country, including China.

The WHO’s persistent publicising of China’s narrative lulled other countries into a dangerous complacency, delaying their responses by weeks. In fact, the WHO actively discouraged action. On 10 January, with Wuhan gripped by the outbreak, the WHO said that it did ‘not recommend any specific health measures for travellers to and from Wuhan’, adding that ‘entry screening offers little benefit’. It also advised ‘against the application of any travel or trade restrictions on China’.

Even after China’s most famous pulmonologist, Zhong Nanshan, confirmed human-to-human transmission of the virus on 20 January, the WHO continued to undermine effective responses by downplaying the risks of asymptomatic transmission and discouraging widespread testing. Meanwhile, China was hoarding personal protective equipment—scaling back exports of Chinese-made PPE and other medical gear and importing the rest of the world’s supply. In the final week of January, it imported 56 million respirators and masks, according to official data.

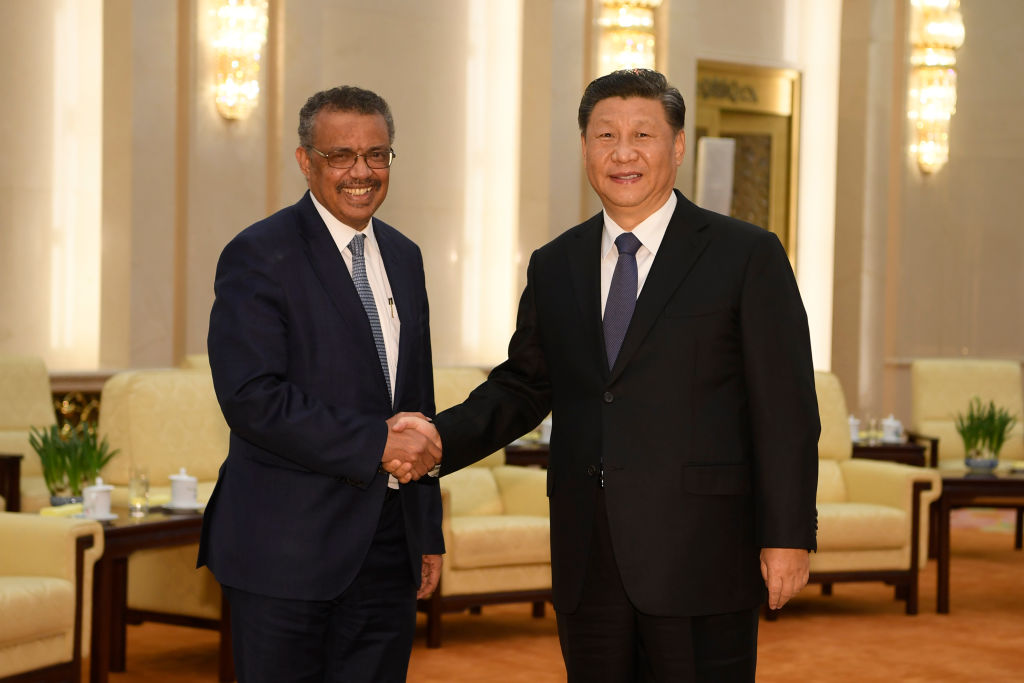

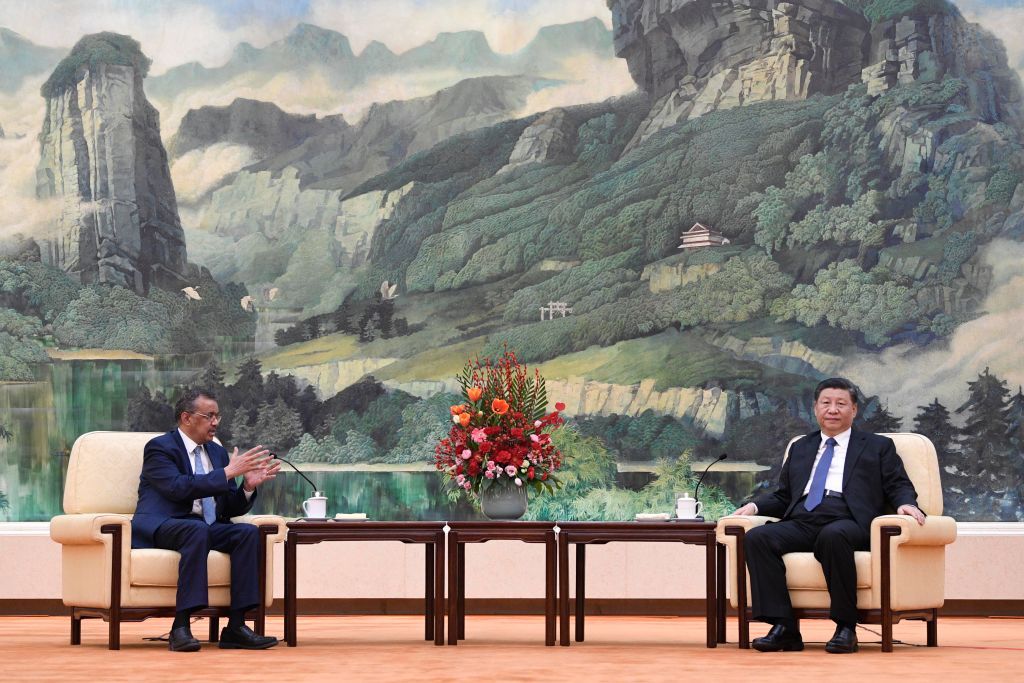

By the time the WHO finally labelled the epidemic a public-health emergency on 30 January, travellers from China had carried Covid-19 around the world, including to Australia, Brazil, France and Germany. Yet, when Australia, India, Indonesia, Italy and the US imposed restrictions on travel from China, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus roundly criticised the actions, arguing that they would increase ‘fear and stigma, with little public-health benefit’.

At the same time, Tedros extolled Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ‘very rare leadership’ and China’s ‘transparency’. The bias has been so pronounced that Japanese Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso recently noted that, for many, the WHO is looking more like the ‘Chinese Health Organization’.

Yet, despite the WHO’s repeated deference to China, the authorities there did not allow a WHO team to visit until mid-February. Three of the team’s 12 members were allowed to visit Wuhan, but no one was granted access to the Wuhan Institute of Virology, the high-containment laboratory from which a natural coronavirus derived from bats is rumoured to have escaped.

China didn’t always enjoy deferential treatment from the WHO. When the first 21st-century pandemic— SARS—emerged from China in 2002, the agency publicly rebuked Chinese authorities for concealing vital information in what proved to be a costly cover-up.

Why has the WHO changed its tune? The answer is not money: China remains a relatively small contributor to its US$6 billion annual budget. The issue is the WHO’s leadership.

Tedros, who became the agency’s first non-physician chief in 2017 with China’s support, was accused of covering up three cholera outbreaks while serving as Ethiopia’s health minister. Nonetheless, few would have imagined that, as WHO chief, the microbiologist and malaria researcher would be complicit in China’s deadly deception.

The WHO’s faltering response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak underscored the imperative for reforms before Tedros was at the helm of the agency. But, rather than overseeing the needed changes, Tedros has allowed political considerations to trump public health.

As the costs of the mismanagement continue to mount, a reckoning is becoming all but inevitable. An online petition calling for Tedros to resign has garnered almost a million signatures. More consequential, President Donald Trump’s administration has suspended the WHO’s US funding, which accounts for about 9% of its budget.

The world needs the WHO. But if the agency is to spearhead international health policy and respond to disease outbreaks effectively, it must pursue deep reforms aimed at broadening its jurisdiction and authority. That won’t happen unless and until the WHO rebuilds its credibility, beginning with new leadership.

Covid-19 is a crisis of globalisation, propagated by around 800,000 international flights carrying over 100 million people across borders every week, along with the cruise liners carrying half a million or so tourists in any week of the year.

The planes have now vanished from the skies and the cruise ships from the oceans, with their passengers disappearing like a swarm of bees back into their hive. International travel will be the last industry to re-emerge after the viral wave has subsided.

The crisis has also brought fresh questioning about the value of international trade and investment. For decades consumers across the world have lapped up the goods manufactured in China with unrivalled efficiency and at an unbeatable cost. Over a 20-year period, from the late 1980s to the global financial crisis in 2007–08, the blossoming of China along with many other emerging nations sent trade volumes soaring from 35% of global GDP to 60%.

It’s as if politicians have suddenly awakened from a long slumber to discover that supply lines—the arteries of globalisation—have transformed into chains of dependence.

As Prime Minister Scott Morrison explained earlier this month, ‘To be an open trading nation—that has been a core part, a core part of our prosperity over the centuries. But equally, we need to look carefully at our domestic economic sovereignty as well.’

He later clarified that this meant ensuring that Australia had profitable, competitive and successful domestic industries with the capability to deliver critical supplies. He indicated it also meant ‘diversifying our trade base’.

The government’s National Covid-19 Coordination Commission, established to guide its response to the crisis, has taken on the task of planning a manufacturing revival. ‘It needs to be modern, efficient, high-tech and focused on the things we need’, the commission’s chair, former Fortescue chief executive Nev Power said, adding that a lot of Australia’s manufacturing was ‘very old fashioned’ and in need of investment.

Power has asked former Dow Chemical chief executive Andrew Liveris to help craft the policy. Liveris told the Australian Financial Review, ‘Australia drank the free trade juice and decided that offshoring was OK. Well that era has gone. We’ve got to now realise we’ve got to really look at on-shoring key capabilities.’

There’s a parliamentary inquiry underway considering whether Australia is too reliant on China and too dependent on foreign investment. The political momentum is probably unstoppable, but a new report from a colleague at the United States Studies Centre suggests that turning back the clock on globalisation will leave us all the poorer.

The study by USSC trade program director Stephen Kirchner explores what steps Australia should take to close the gap between Australian and American living standards and productivity. Australia has persistently lagged the United States by 15% to 20%.

There was a period in the 1990s (often attributed to the economic reforms of the Labor governments of Bob Hawke and Paul Keating) when the gap narrowed, which greatly reduced levels of industrial protection while opening Australia’s economy to global capital markets with the floating of the Australian dollar.

Those reforms exposed Australian businesses to global competition and made it possible for them to expand internationally. Without the protection of high tariff walls, the business sector had to become more productive if it was to compete.

Australian businesses proved adept at deploying developments in information technology and telecommunications in ways that boosted productivity. This was also a function of the new openness of the economy to global influence.

Kirchner says the lack of significant economic reform since the early 2000s and the growing burden of regulation in Australia relative to the US have caused the gap to widen again. He argues that it can be closed only by further exposing the Australian economy to the global economy.

The Swiss KOF Economic Institute compiles an index measuring the global connection of nations taking in such variables as ease of cross-border flows of goods, services, investment, migration and capital. Australia is middle-ranking overall, but on the economic sub-index it ranks second last, with only the US below it among the 59 nations that are tracked.

As the country with the highest productivity in the world, the US doesn’t suffer from its relative insularity; however, improvements in Australia depend upon its ability to draw in the latest innovation, business practice and expertise from around the world.

Rankings on the KOF Globalisation Index have an established cross-country relationship with living standards. Kirchner estimates that a 1 percentage point improvement on the index would lift Australia’s productivity by 0.3%.

If Australia matched the global exposure of Germany or the UK, which rank 23rd and 24th on the index, its productivity would be 5 percentage points higher, closing around a third of the gap with the US.

The study also observes that for every percentage point gain in US productivity, Australia’s productivity gains 0.95 percentage points. While we largely track the US, we never catch up.

He notes that Australia’s high migration levels, at least until the Covid-19 crisis, have contributed to productivity. More than half the increase in Australian graduates since 2013 hold degrees from overseas universities or are non-citizen holders of Australian degrees. That addition to Australia’s human capital has come without any investment from Australian taxpayers.

Kirchner argues that government policy should aim to place the economy at the frontier of globalisation if Australia is to catch up with the US. ‘Increased foreign direct investment, freer digital commerce and increased immigration offer significant and under-appreciated productivity benefits that require few changes in legislative or policy frameworks to capture.’

In the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, public policy is heading in precisely the opposite direction. Having accepted a dramatic fall in economic activity and living standards as a necessary price for combating the virus, it may be that politicians are prepared for further sacrifices in the cause of economic sovereignty.

The coronavirus pandemic will affect the power of countries in different ways. The biggest impact will be reductions in the economic, and therefore military, strength and relative power of competing major states.

The American historian Walter Russell Mead says that ‘the balance of world power could change significantly as some nations recover with relative speed, while others face longer and deeper social and political crises’.

Henry Kissinger’s view is that ‘the world will never be the same after the coronavirus’. He stresses the need for the democracies to defend and sustain the liberal world order. A retreat from ‘balancing power with legitimacy’ will cause the social contract to disintegrate both domestically and internationally. The challenge for world leaders is to manage this crisis while building the future, he says, and ‘failure to do so could set the world on fire’.

Most importantly, the pandemic has widened the confrontation between the US and China, with uncertain results for Australia.

China stands to be a loser, not because its economic power won’t bounce back, but because its ideology forced this pandemic on the rest of the world when it could have been contained at the very outset. By suppressing information about the outbreak in Wuhan, the authorities lost the world at least four to six vital weeks when Beijing could have contained what is now an unprecedented global disaster.

China had been warned about the origins of the 2003 SARS epidemic, which, like the coronavirus, started in a major Chinese city. In both instances, the virus appears to have been transmitted to humans from wild animals sold in China’s wet markets. The leaders from President Xi Jinping down will carry the legacy of their denial and repression as a millstone that will be long remembered outside China as causing large numbers of unnecessary deaths worldwide.

In one fell blow, China has fatally undermined the advantages of globalisation—not only in a health sense, but also in Western countries’ dependence on China for medical drugs and equipment. Countries such as the US will diversify away from such reliance on China, even if that increases costs.

America’s reputation has also been damaged, by its inability to provide leadership in arguably the worst crisis since the end of the World War II. Allan Gyngell, a former head of Australia’s Office of National Assessments, has said that the US ‘looks irrevocably weakened as a global leader’. While China is now belatedly ‘offering its resources and experience in handling the virus to build relationships with other countries’, including in Europe, he notes that the US is ‘absent from any international leadership’.

President Donald Trump has failed to provide consistent and credible responses as the crisis has unfolded.

Rather than prompting a multilateral response, the Covid-19 crisis has ramped up extreme nationalism and harsh border-protection measures as the virus spread rapidly from one country to another. Nations are becoming acutely introverted as they give absolute priority to staving off massive deaths and the threat of calamitous economic damage, and even collapse for some.

In the longer term, this pandemic will likely fade away and most, but not all, advanced economies will snap back into economic growth. But it will be the most damaging crisis by far that our populations have experienced. The remarkably sudden and abrupt onset of this calamity will lead to greater uncertainty, and even fear, about our futures.

Australia will find itself weaker in the post-pandemic world. Serious economic damage may well have a long-term impact on cohesion and trust in our society. The reputation of our American ally has been badly damaged. And it remains to be seen whether we should allow our trade with China to resume its previous predominance.

A major lesson we should learn is to diversify our economic relationships and become more self-reliant, including in terms of our national security. This will involve a radical rethinking of the credible circumstances in which we will have to take the lead during security crises in our region without American involvement.

We will need to re-examine our vulnerabilities in such key areas as fuel supplies, critical infrastructure, and protective and offensive cyber resources. We should rapidly develop a new strategic posture, giving high priority to long-range missile attack capabilities to deter any power from threatening our strategic space.

A further serious geopolitical issue should not be underrated. It’s highly likely that neighbouring countries, critically important to us strategically, will suffer severe structural damage to their societies and economies. The health systems of Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Timor-Leste, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu may be overwhelmed, with very high death rates.

They will need our help to fight this virus and to restructure their economies. Australia and New Zealand should lead the way. If we don’t, China will probably step in and offer massive economic and medical assistance as it seeks to entrench a sphere of influence in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific, which will directly threaten our own security.

The future of the democracies in Australia’s primary area of strategic interest to our north and east must deeply concern Australian policy planners. We should ensure that our natural focus on our own serious problems doesn’t lead us into the trap of isolationism.

Indonesia, with over 270 million people, and Papua New Guinea, with nearly 8 million, must be priorities. If the coronavirus overwhelms their potentially fragile societies, we should be prepared to contribute generously to a prolonged and expensive effort to rebuild their health systems and economies. It’s not in Australia’s interests to see such strategically crucial neighbours collapse.

Australia’s former ambassador to Indonesia John McCarthy believes that the Covid-19 crisis could fuel support for extremist groups in Indonesia and place the nation’s stability at risk. We need to think carefully about the geopolitical impact of the virus on countries in our immediate region and give it our highest priority.

The nation-state has decisively reasserted itself as a prime actor in the global fight against Covid-19. There will be much greater calls for self-reliance, but as the international community becomes more fractious and the liberal order recedes, we must not lurch into a new bout of introversion.

The history of coronaviruses is littered with environmental degradation, superstition, rampant illegal trading in wildlife, and complacency.

Earlier this century, a global panic was triggered by one such virus, SARS, and there were what look in hindsight like half-hearted attempts to develop a vaccine. Some formulations worked in animal tests but were shelved when they failed to produce the right antibodies in people. That research faded away when the world mistakenly believed the SARS threat had passed.

The new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, which causes Covid-19, has shown the modern medical world to be worryingly on the back foot, while foolish old-world superstitions persist about the medicinal power of wild animal parts from the most endangered and most trafficked species. This illegal industry is backed by serious and organised crime.

Animal-borne infectious diseases such as those caused by coronaviruses are an increasing threat to global health and security. More than 60% of 335 new diseases that emerged between 1960 and 2004 were zoonotic. Increasingly, these diseases are linked to habitat destruction and ecosystem disruption, which come from urbanisation, deforestation, logging, mining and rapidly increasing human populations.

The global illegal trade in wild animal products helps fuel epidemics, often in countries in which ‘wet’ markets operate. There, live animals and fish, often called ‘bushmeat’, are bought and sold. Interpol and the non-governmental organisation TRAFFIC say this trade has long been linked to gun and drug crime and illegal deforestation and mining.

Weak international laws make it difficult for NGOs like TRAFFIC to track and prosecute the criminal gangs behind the wildlife trade. Although the wet markets in China, including the one in Wuhan, were officially shut down in the initial stages of the outbreak, many have since reopened.

China also instituted a ban on the sale of wild animals for human consumption, which remains in place. But wildlife experts believe the trade has gone deeper underground and animals are now being kept in even worse conditions. That allows viruses to cross to new species. In Gabon, traders are said to be keeping pangolins hidden, though they are still selling them.

Unless the international wildlife trade is stopped, new coronaviruses will pose a threat to human communities. Many nations don’t even have laws making the importation of banned wildlife and products illegal. Where legislation does exist, penalties can be inconsistent.

Coronaviruses are known to be widespread in bats, and in March 2019 China was identified by virologists from Wuhan as a country at particular risk of a SARS- or MERS-type epidemic.

SARS is believed to have crossed from bats to people via civets, while MERS made the transition via camels. A recent paper in the journal Current Biology confirmed that pangolins are the most likely intermediate species in the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from bats to humans.

Our new world of zoonotic diseases requires much more than vaccines. Governments are increasingly reluctant to police environmental and wildlife laws. Those that allow environmental protections to be overridden or ignored include Australia, Brazil and China.

Weak environmental protection laws in Western countries reflect how little global leaders think or care about the cause-and-effect linkages between environmental stress and the health of human populations. The costs of not caring have not yet sunk in.

Without control of both the illegal wildlife trade and more general environmental destruction, development of antivirals and vaccines will fall short. Over time, we should expect new global zoonotic diseases far worse that Covid-19 to emerge. Taking environmental and animal crimes seriously will give better insight into how these viruses spread into human populations.

The Coalition for Epidemic and Preparedness Innovation is a global alliance that finances and coordinates the development of vaccines against emerging infectious diseases. A coalition of scientists that includes researchers from the University of Queensland and the CSIRO are working on producing a vaccine against Covid-19 vaccine; pre-clinical trials have started for two potential candidate.

But vaccine development is slow and fraught with issues of safety and the difficulties of mass production and distribution. It’s not known yet whether the vaccines being trialled will produce effective antibodies in people. The world will need to keep managing Covid-19 without a vaccine for many months to come.

The Covid-19 crisis is demonstrating that protecting nature and wildlife is not a luxury but a necessity if we are to save lives, livelihoods and economies. Added challenges come from the fact that wild animals are now increasingly ‘farmed’ alongside poultry and pigs.

Future epidemics will include varieties of influenza, which can spread to humans from chickens and pigs, as happened with H1N1 and H5N1. Farming practices need serious scrutiny at the global level.

We have only just entered this new era of viruses and our current medical technologies are woefully inadequate to treat us in this new world. Many experts still operate in silos and there’s been far too little international cooperation among specialists such as epidemiologists and virologists.

Hopefully, the scale of the destruction wrought by this latest coronavirus will force the changes the world needs.

Long before people and goods were traversing the globe non-stop, pandemics were already an inescapable feature of human civilisation. And the tragedy they bring has tended to have a silver lining: perceived as mysterious, meta-historical events, large-scale disease outbreaks have often shattered old beliefs and approaches, heralding major shifts in the conduct of human affairs. But the Covid-19 pandemic may break that pattern.

In many ways, the current pandemic looks a lot like its predecessors. For starters, predictable or not, disease outbreaks have always caught the authorities off guard—and they have often failed to respond quickly and decisively.

Albert Camus depicted this tendency in his novel The plague, and China’s government embodied it when it initially suppressed information about the novel coronavirus. US President Donald Trump did the same when he minimised the threat, comparing Covid-19 as recently as last month with seasonal flu. As an official in Camus’s novel said, the plague is nothing but ‘a special type of fever’.

Leaders’ lack of foresight has often left people with only one real defence from disease outbreaks: social distancing. As Daniel Defoe noted in A journal of the plague year, his memoir of the bubonic plague outbreak in London in 1665, the municipal government banned events and gatherings, closed schools and enforced quarantines.

Nearly two millennia before London’s Great Plague, during the epidemic that killed at least a third of Athenians near the end of the Peloponnesian War, the Greek historian Thucydides observed that if people made contact with the sick, ‘they lost their lives’. As a result, many ‘died alone’, and funeral customs were ‘thrown into confusion’. And, owing to the high death toll, the dead were often ‘buried in any way possible’.

During the Covid-19 crisis, lockdowns and other social-distancing protocols have similarly prevented people from visiting their dying loved ones and upended funeral traditions. In China, families are reportedly encouraged to bury their dead quickly and quietly. Satellite images show mass graves being dug in Iran. New York City officials have also ramped up mass burials, intended for those who have no next of kin or families who can afford a funeral. Some cemeteries in London have run out of graves.

Another parallel between the current pandemic and its predecessors is the tendency to embrace experimental palliatives. During the pandemic of so-called Spanish flu a century ago, scientists blamed bacterial infections, and designed treatments accordingly. We know now that influenza is caused by a virus; no bacterial vaccines could protect against it.

Of course, researchers working on Covid-19 have a much more advanced understanding of disease. But, as we await a bespoke cure or vaccine, existing antivirals—such as those long used for malaria—are being tested, with mixed results. The use of one such drug, chloroquine, has raised concerns after patients receiving it showed signs of heart-related complications.

And then there are the bogus cures that invariably emerge—‘infallible preventive pills’, as Defoe called them. Today, charlatans—aided by social media—have made similarly false and dangerous claims, suggesting that anything from snorting cocaine to drinking bleach can protect against Covid-19. Trump himself has touted hydroxychloroquine as a potential ‘game changer’, despite the lack of testing—prompting one couple to attempt to self-medicate. The husband died; his wife barely survived.

The economic disruption caused by Covid-19 also has plenty of precedent. The second-century Antonine Plague caused one of the most severe economic crises in the history of the Roman Empire. The Plague of Justinian—which initially erupted in 541–542 and recurred intermittently for two centuries—did the same to the Byzantine Empire.

Epidemics not only ravage economies, but also throw societal inequalities into sharp relief, deepening mistrust in the status quo. Disease may not discriminate between rich and poor, but their living conditions always make the poor and marginalised more vulnerable. Machiavelli, who witnessed—and probably died in—the plague in Florence in 1527, viewed the outbreak as the direct result of misrule. Criticisms of China, Trump, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and others have echoed this sentiment.

Others view epidemics through the lens of conspiracy theories. Marcus Aurelius blamed Christians for the Antonine Plague. In Christian Europe, the 14th-century Black Death was blamed on Jews.

Imagined culprits behind the Covid-19 crisis include radiation from 5G technology, the US military, the Chinese military and—no surprise—Jews. Iran’s state-controlled media has warned people not to use any vaccine developed by Israeli scientists. Publications in Turkey and Palestine have defined Covid-19 as an Israeli biological weapon. White supremacists in Austria, Switzerland and the US have blamed the Jewish financier and philanthropist George Soros, who they believe hopes to thin out the world population and cash in on a vaccine.

Despite these similarities, the Covid-19 pandemic is likely to stand out in a crucial way: it is unlikely to upend the established order. The Antonine and Justinian plagues encouraged the spread of Christianity throughout Europe. The Black Death drove people towards a less religious, more humanistic view of the world—a shift that would lead to the Renaissance. The Spanish flu prompted uprisings, massive labour strikes and anti-imperialist protests. In India, where millions died, it helped to galvanise the independence movement.

The Covid-19 pandemic, by contrast, is more likely to reinforce three pre-existing—and highly destructive—trends: deglobalisation, unilateralism and authoritarian surveillance capitalism. Almost immediately, calls for reducing dependence on global value chains—already gaining traction before the crisis—began to intensify. Efforts by the European Union to devise a common strategy have again exposed the bloc’s old divisions. Trump has now decided to suspend US funding allocated to the World Health Organization. And, under the cover of the fight for life, authorities beyond just China or Russia are trampling on liberties and invading personal privacy.

Two world wars have shown that a global order organised around egocentric nationalism is incompatible with peace and security. The pandemic has highlighted the urgent need for a new balance between the nation-state and supranational institutions. Without that, the devastation wrought by Covid-19 will only increase.

Covid-19 has shone a spotlight on accountabilities and practices in the international cruise ship industry. Until now, the developed world has been in love with the industry, which has been growing at 15% per year, offering a range of experiences from small luxury vessels cruising the Antarctic to floating parties in tropical climes. But the pandemic has shown that cruise shipping is essentially an unregulated industry that has thrived in an environment lacking rules. Will Covid-19 change that?

More than 100 cruise ships with thousands of crew on board are currently sitting off the coast of the United States. Most ships of this size are potential hotspots for Covid-19—they house large numbers of people in close confines, with little ability for social isolation. The US Navy is grappling with the same problem with the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt in Guam, but, unlike the military, the cruise ship industry isn’t an instrument of state and companies have been resisting government pleas for them to leave and return to their home ports.

One of the reasons nations struggle with managing ships in their waters is the practice of using ‘flags of convenience’. Under longstanding maritime law, all ships must be registered to a nation-state. Flying a flag of convenience is a practice that enables a ship to be owned and operated by a company in one nation but registered in another. Often, these ships are registered in a country that doesn’t have the means to support them in remote corners of the world and that offers cheap registration with minimal regulation of safety and employment conditions.

The practice of using flags of convenience began during the Prohibition era when the US banned the transport of alcohol for human consumption and shipping companies looked for alternative business options. That period extended from 1920 until 1933 and led to many shipping companies registering their vessels in Panama in an attempt to bypass the legislation.

Flags of convenience became more widely used following World War II with the expansion of the maritime trade. By offering registration as a commodity, several small nations saw opportunity in providing low registration fees, relaxed regulation, an easy registration process, and reduced standards surrounding inspection, employment and other conditions. These nations include well-groomed tax havens like Bermuda and states like Liberia, Sierra Leone and the Marshall Islands. Many of these countries have little to no ability to control the behaviour of the ships’ owners or captains.

In cargo ships and oil tankers, the practice facilitated the hiring of crew from international labour pools without the need to adhere to labour laws in home countries, such as paying the minimum wage, or to respond to seamen’s unions. Of the 100,000 British sailors registered in the 1960s, only around 27,000 remained employed by the mid-1990s. At that time, there were around 1.3 million seafarers drawn from places with cheaper labour costs such as the Philippines, Indonesia, South Asia, Russia and Ukraine.

In addition, merchant shipping has required fewer and fewer crew over time—a 100,000-ton bulk carrier today may have only 15 crew members on board. Self-isolating 15 individuals on a ship up to 450 metres long isn’t a problem compared with trying to quarantine the huge numbers of people travelling and working on cruise ships.

It was the ever-expanding cruise ship industry that garnered the most advantage from flags of convenience, primarily to minimise labour costs. A ship carrying 4,000 or 5,000 passengers needs hundreds of crew to feed, service and pamper what amounts to the population of a small city.

The cruise industry operates on fine margins. On average, the revenue per passenger on a typical cruise is US$1,791 and expenses are around US$1,564, a margin of 12%. Without passengers, few of the expenses can be offset, so there’s no motivation to sail the ship halfway around the world to a home port without passengers.

As we’ve seen during the Covid-19 crisis, if a port won’t allow the crew ashore, and the owners won’t pay for them to return home, the ship and crew are stranded at sea like some 21st century Flying Dutchman. Many of the crew are under contracts that provide for travel home only two or three times a year. They are now in lockdown on board these ships, with no obvious way home. What effect will that have on their mental and physical health?

The pandemic has raised serious questions about the practice of using flags of convenience. Should we continue to allow the cruise industry to operate in the shadows without rigorous regulation and oversight? Or is it time to end the practice and return to requiring ships to be registered in the nation-state of the company that owns them?

Plagues bring out the best and worst in pharaohs, as they do in party secretaries, presidents, and directors of the World Health Organization. There’s nothing like a high-pressure crisis to test a leader’s mettle.

In the US, the pandemic has exposed a president who is inclined to blame others for America’s troubles and to claim personal credit for remedial action. In China, it has exposed the Chinese Communist Party as an equally narcissistic institution shielding its followers from ‘hostile foreign forces’ while advancing implausible solutions for the world’s problems. China’s party leadership denies culpability for the global pandemic while demanding a note of thanks simply for doing what it should.

Between them, leaders in China and the US are presenting problems for the one institution on earth designed specifically to manage communicable disease outbreaks, the World Health Organization. Covid-19 has exposed a leadership team in the WHO with little experience managing an outbreak of non-communicable narcissistic disorder in the world’s two most powerful countries.

To this point, the damage wrought by China’s leadership is far and away the more serious.

The WHO acceded a year ago to Chinese government pressure to acknowledge traditional Chinese medicine, since revealed as a plausible source of the Covid-19 pandemic. At the time the coronavirus was leaping from animal to human hosts in Wuhan in October 2019, CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping was telling a conference in Beijing that he applauded ‘efforts to promote [traditional Chinese medicine] internationally and fully develop its unique strength in preventing and treating diseases’. For some years he had been lobbying the WHO to recognise traditional Chinese medicine as a legitimate form of medical treatment. In May 2019, the WHO’s governing body bowed to Beijing’s pressure.

Scientists and public health specialists were appalled. One was quoted as saying that the WHO’s ‘failure to specifically condemn the use of traditional chinese medicine utilising wild animal parts is egregiously negligent and irresponsible’.

Second, late last year the WHO ignored questions from Taiwanese health authorities alerting the agency to signs of human-to-human transmission in Wuhan at a time when Beijing was downplaying concerns over social transmission. The WHO is obliged by the terms of its agreement with China to deny Taiwan formal recognition, but there’s nothing in its agreements compelling the WHO to ban Taiwan’s participation in health matters or reject the specialist knowledge and expertise Taiwan can bring to the table. This is a further result of political lobbying from Beijing.

At that time, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus accused the government of Taiwan of levelling racist slurs against him, an accusation fiercely denied by Taiwan but reinforced by an online army of trolls based in China, pretending to be Taiwanese nationals, ‘apologising’ for offending Tedros. Once again this suggests unhealthy collusion between the WHO leadership and Beijing.

By his actions, the director-general inflicted reputational damage on the WHO. Taiwan’s exceptionally low rate of infection and mortality in the Covid-19 pandemic has made Taiwan a poster child advertising the benefits of being excluded from the WHO and relying instead on alternative sources of information and analysis. The WHO doesn’t come out well when a country so clearly benefits from having nothing to do with it.

Third, the WHO was slow in sharing information about the Covid-19 pandemic and, as US President Donald Trump reminds us, it parlayed misinformation from China in its public communications. But Trump is wrong in attributing this to ‘China-centric’ behaviour on the agency’s part.

There was certainly misinformation coming out of China. Local officials in Wuhan delayed reporting evidence of human-to-human transmission to Beijing for some weeks after the earliest cases came to their attention, and they prevented reliable informants among health professionals from sharing what they knew. Authorities in Beijing remained silent for a further week after receiving confirmation of local human-to-human transmission in mid-January. Xi only went public on 20 January.

That was not the WHO’s doing. The agency may have been naive in taking China’s authorities at their word, but as an organisation made up of members, that’s how the WHO operates: it shares information offered by its member states. When they can manage it, individual member states are responsible for gathering and sharing information on domestic health issues. The WHO, on the other hand, is uniquely responsible for monitoring the point at which domestic public health issues become global ones.

A key question for the WHO is how it managed reporting on human-to-human transmission beyond China’s borders. On this pivotal question there’s little basis for the claim that the WHO showed undue caution on account of pressure from China.

In fact, it had other reasons to tread very carefully. Early in the spread of Covid-19, health experts at the WHO were keen to avoid coming across as unduly alarmist in their public statements because they had been roundly condemned a decade earlier by European and other Western countries for taking a more proactive stance during the 2009–10 H1N1 pandemic. When that pandemic failed to unfold on the scale the WHO anticipated, the agency was accused of crying wolf.

That earlier H1N1 controversy is referenced in recent WHO statements on Covid-19 as a kind of cautionary lesson framing its approach to the global spread of the new disease. Addressing a press conference on 17 February 2020, WHO Executive Director Michael J. Ryan reminded all media present that WHO officials ‘need to be careful’ in handling information on Covid-19 in light of earlier public criticism over the H1N1 pandemic.

In this case, his caution was ill-advised, but it had nothing to do with China. In 2010 it was European agencies that blasted the WHO for sounding a false alarm on H1N1. The chair of the Council of Europe’s health committee was reported as saying that the WHO’s early call was ‘one of the greatest medical scandals of the century’ resulting in the waste of US$18 billion on preventive measures and pharmaceuticals to little purpose. The emergency committee advising the WHO was alleged to have been ‘subject to undue commercial influence’ from the big pharmaceutical companies that profited from the WHO’s H1N1 call.

Senior staff at the WHO still bear the scars of that controversy and tread cautiously before making public statements about the global spread of infectious diseases, not because they are ‘China-centric’ but on account of trenchant Western media criticism endured in years past.

The fate of the WHO now lies in the hands of Washington and Beijing, the one threatening to cut off funds, the other willing as ever to trade favours for improper influence. Beijing’s influence over the organisation has little to do with funding. China is the world’s second largest economy and over the decades has been an enormous beneficiary of WHO programs. And yet in 2019 its financial contributions to the WHO were less than those of Norway or Australia, let alone the US or UK.

China’s political influence is out of all proportion to its financial contributions because it controls access to one-fifth of the world’s population—a critical factor in world health reports—and because it can marshal support among smaller nations across the UN system to secure strategic advantages throughout the UN system. Beijing’s favoured currency is trading in political favours, and it will go on minting favours indefinitely whether or not Trump follows through on this threat to withdraw funding.

It is up to other countries, including Australia, to expose the damage Beijing’s collective narcissism and Trump’s narcissistic personality disorder are visiting upon us all. We could start by pressuring the WHO to reverse its decision on traditional Chinese medicine, and to make way for Taiwan at the table, and we could continue working together to ensure that the WHO puts health ahead of politics whenever it confronts unreasonable demands from member states.

Trump is often likened by his fervent followers to a latter-day Moses leading his people out of bondage to the promised land. But he is just another pharaoh lashing out to escape responsibility for his own actions.