How to deal with the increasing risk of doing business with China

Can Australia stop the Chinese government’s economic coercion against our government and businesses? Yes.

All it would take is for Australian political leaders and parliaments to align our national policies, laws and directions with those of the Chinese government. Shutting up when we have differences and making decisions aligned with Beijing’s acts, wishes and decisions would be the most business-friendly China policy for Australia and every other country to adopt.

That’s pretty much what a set of interests and voices in Australia is calling for when it talks of ‘resetting the relationship’.

But it’s also very difficult. Unavoidable differences in national interests are becoming more stark as China’s national power grows and as the Chinese Communist Party uses that power more coercively domestically and internationally.

China’s aggressive expansion of its boundaries through forcible seizure of South China Sea landforms and the coercive patrolling of the maritime area within its large ‘nine-dash line’ claim is one example.

In Australia, Chinese foreign interference has led to new laws and seen cyber hacking of our parliament and political parties. And now, the Chinese ambassador’s threats of economic coercion have been followed by actual coercion disguised as arcane technical difficulties around our barley and beef exports.

The pressure is intended to force policy change in Australia—to stop Australia building international support for an inquiry into the pandemic’s causes.

Economic pressure on industries like barley and beef doesn’t just make a direct point to our political leaders about the consequences of acting against the Chinese government’s interests; it creates pressure within Australia on those leaders. Hence the free advice that former politicians and business types are giving the government.

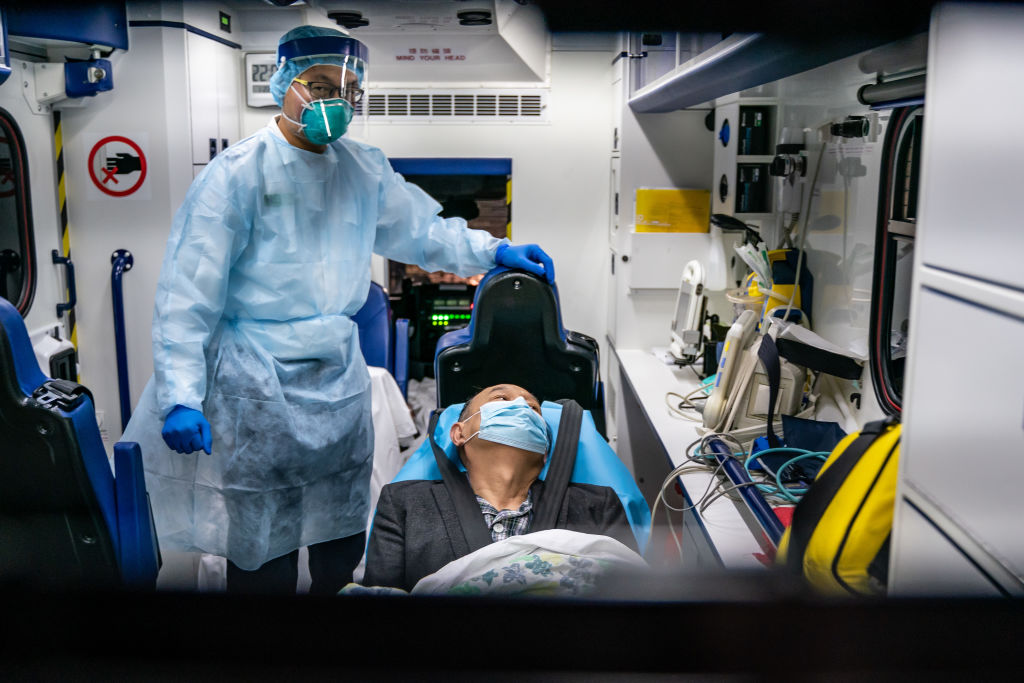

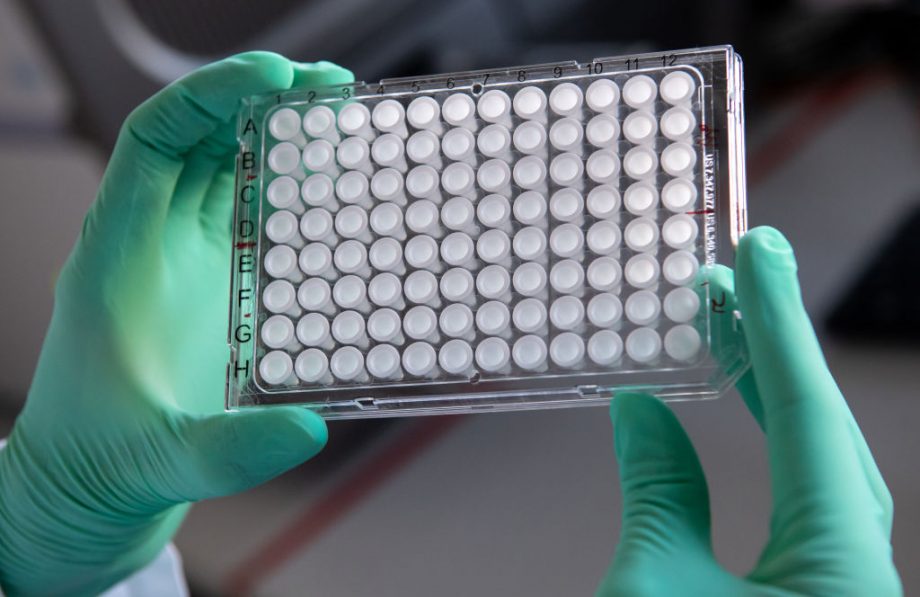

Let’s remember what this latest bout of coercion is about. The pandemic started in China, according to the World Health Organization, and has now infected some 4.4 million people, killed more than 300,000 worldwide and caused what looks like a global depression. Australia’s prime minister has called for a credible international inquiry into how the pandemic started and what was done, and not done, to prevent its spread.

So, 80 million people don’t see a credible international inquiry as in their interest—because they’re members of the CCP. Another 7.7 billion occupants of planet earth do want to know how this pandemic happened and how we can prevent future ones.

A credible inquiry will detail the actions of Chinese government officials, leaders and authorities in the early days of the pandemic that repressed information and prevented early international action with and in China that may have prevented the pandemic or lessened its impact.

This is a radioactive issue for the Chinese government domestically, because it cuts to the heart of its capacity to govern in the interests of the people rather than itself. And it’s a radioactive issue internationally because a credible inquiry would reflect on the Chinese government’s trustworthiness and competence.

It would also deflate the misinformation campaign China is waging to obscure the pandemic’s causes and virus’s origin. The stakes are enormous for the Chinese government—which explains its blunt economic coercion and fiery statements.

For Australia, one easy answer would be to stop pushing for an inquiry and leave it to others to prosecute. But making it somebody else’s problem is exactly what the Chinese government wants. If Australia stops building support for the inquiry, the lesson to others is clear: don’t be the first to speak up against Chinese acts that are against your interests.

It would also show that coercion works, and all bullies love it when their behaviour brings rewards. The result is not less bullying.

Australia taking the lead on key global issues matters. The role of 5G technology in national security and economic prosperity is an example. Australia’s carefully explained decision to exclude high-risk vendors from building our 5G network sparked a wave of deep international consideration. What we do matters—and the Chinese government knows this.

And we are not alone. Many nations are dealing with a coercive, powerful Chinese government that uses its economic weight to pressure them, all because they’ve acted in their national interests. Norway suffered Chinese economic coercion over the Nobel prize that affected its smoked salmon exports. South Korea suffered boycotts of consumer goods when it installed a US missile defence system for its own security against North Korea. Japan faced down Chinese government threats on critical mineral exports. And we’ve seen testing of Australian thermal coal exports for radiation (!) as one of the ‘technical difficulties’ coinciding with Chinese government displeasure.

Even the US National Basketball Association and the world’s airlines have been subjected to coercion, in the NBA’s case because an official had the nerve to support pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong. The airlines incurred disfavour over their naming of Taiwan on flight boards.

It’s not tone or management of the relationship that’s causing Chinese coercion. It’s a clash of interests and values. Until Australia and other countries stop being democracies, stop thinking that freedom of speech and human rights are important, and stop taking decisions in the interests of our own sovereignty and security, we will bump into Chinese government interests and actions.

As Chinese government aggression increases, the business risk for all companies trading with China is growing. The pandemic is an example, but it has really just highlighted a problem that was growing before it.

Counterintuitively, it’s a great time for Chinese authorities to wield the economic coercion weapon. Every government and company is anxious about its economic viability post-Covid-19, and every part of the global economy is depressed because of it. So, each sale and market becomes more important, and threats become more powerful.

And Chinese consumer demand is depressed because, despite the hype, China is not back to business as normal. So, threats to reduce trade in multiple commodities are free gifts for the Chinese government. Chinese demand for Australian beef and barley is likely to fall anyway because of deadened consumer demand. Why not pretend the pain inflicted on our industries is a result of the clash between our governments?

Let’s keep calm and stay clear and simple on what our interests are and why decisions are being taken and directions pursued. Dealing with each issue on technical grounds while realising it’s part of a bigger picture is smart, and that’s what the government seems to be doing. We also need to remind ourselves that cutting trade with Australia inflicts pain on the Chinese economy, and that’s not a simple calculation for the regime.

The bigger remedy, though, is for all businesses—and that includes our universities—to factor increasing risk into doing business with China. This adjustment to corporate planning and strategy will do as much to diversify our economy as a set of government policies. Over time, it will reduce the leverage that the Chinese government has over our economy and our parliament, and that’s no bad thing.