Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

On 23 February, India accounted for 11 million of the world’s 112 million Covid-19 cases and 156,498 of 2,848,247 world deaths. Only the US had more cases and the US, Brazil and Mexico have recorded more deaths than India. Yet India’s Covid mortality rate of 113 deaths per million—only 35% of the global average of 319—places it 112th of 221 countries and other locations (including, for example, the cruise ship Diamond Princess) covered by Worldometers.

I discussed India’s Covid situation in the global context in an academic article in January. What’s interesting since then is the extent to which India is suddenly attracting world attention. One component of this is the surprisingly low mortality rate considering the many adverse initial conditions in the country.

The second is the overdue recognition that India is a vaccine superpower with a US$42 billion pharmaceutical sector, including US$20 billion worth of exports in 2019–20, a point I alluded to in a Strategist article in June. In combination with the country’s emphasis on vaccine affordability and access, this gives India the potential to be the pharmacy to the world.

It also gave India the self-confidence to refuse emergency-use authorisation for the Pfizer vaccine, based on trials in Germany and the US, unless it met the Indian regulator’s demand for a local safety and immunogenicity study as a ‘bridging trial’. Pfizer withdrew its application.

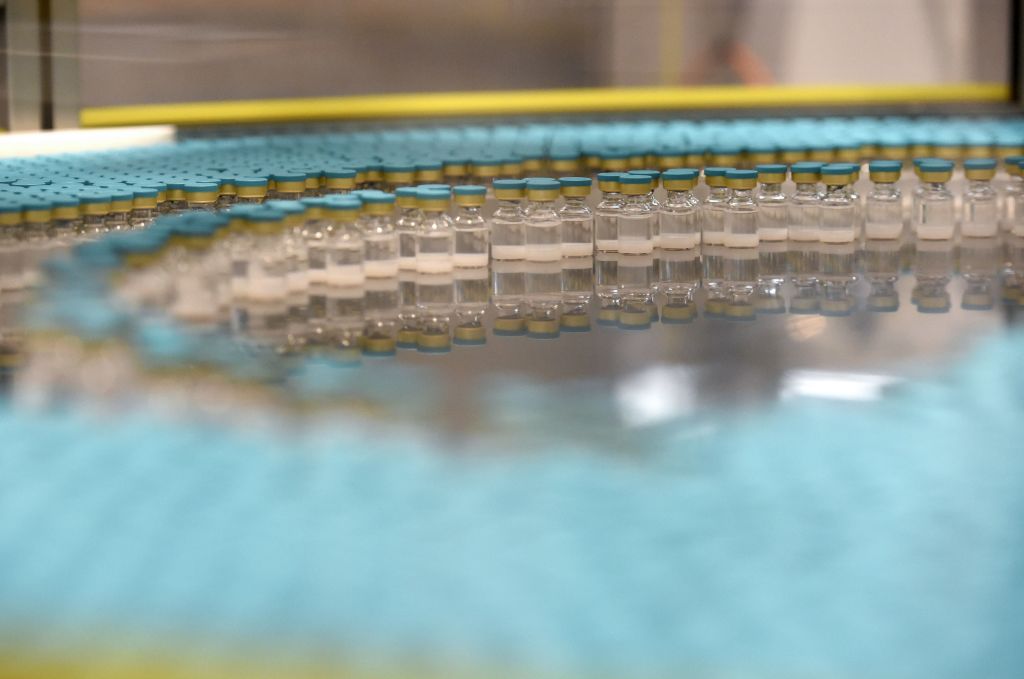

As with everything else, India does things by scale. In January, the BBC noted that India produces 60% of world vaccines by number of doses. The Guardian published an interview with Adar Poonawalla, CEO of the Serum Institute of India, the single largest manufacturer of Covid vaccines in the world by volume, on 14 February. It expects to be making 100 million doses per month by the end of March. Another company, Bharat Biotech, has the goal of making 200 million vaccines annually.

Matching India’s impressive private-sector manufacturing capacity scaled up to meet world needs is the emerging character of India’s vaccine diplomacy. The key consideration driving the country’s vaccine exports is a careful balance between world needs and demand. This echoes the government’s commitment to prioritise the poor, the vulnerable and the frontline workers in the domestic vaccination drive.

India has enormous experience in implementing mass-vaccination programs for smallpox, tuberculosis, polio and other illnesses. At full stretch, India will be vaccinating 85 million people per month. By 22 February, in 38 days India had vaccinated 11 million people. The goal is to cover 300 million people by the end of July.

India’s donations to neighbouring countries Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Maldives and Bhutan are nearing 6 million doses. India has pledged another 10 million doses to Africa and 1 million to UN health workers. As Indian vaccines arrived in Johannesburg, Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar tweeted on 2 February: ‘In it together. Made in India vaccines land in Johannesburg, South Africa. #VaccineMaitri’ (maitri means friendship.) Afghanistan, Myanmar, Mauritius, the Seychelles, Kuwait, Morocco and Brazil are also in queue.

Meanwhile, Pakistan has been the beneficiary of Chinese largesse with a donation of 1 million doses of the Sinopharm vaccine in two consignments. At the virtual meeting of the World Health Assembly on 18 May, President Xi Jinping affirmed that a coronavirus vaccine would be ‘a global public good’ and represent ‘China’s contribution to ensuring vaccine accessibility and affordability in developing countries’.

It’s worth noting that this language is a challenge to the big (by market capitalisation) Western pharmaceutical firms’ drive to enforce intellectual property rights on all countries. China and India have been the leaders against that, arguing for affordable access for the people of poor countries as a higher priority.

Peter J. Hotez, co-director of the Center for Vaccine Development at Texas Children’s Hospital and a former science envoy in the Obama administration, argues that compared to China and Russia, India’s approach is ‘more of a pure expression of true “vaccine diplomacy”’. ‘The likelihood is that India is going to rescue the world in making low-cost high-quality vaccines available and responding quickly to the new variant to adjust their vaccines accordingly.’ By contrast, China seems more intent on linking exports to exerting political influence, he said.

Duke University’s Global Health Institute notes that, in an ugly outbreak of vaccine wars, rich nations comprising just 16% of the world’s population (including Australia) have cornered 60% of the global vaccine supply (4.2 billion doses) and low-income countries have secured only 270 million doses. Yet even on purely self-interested calculations, the equitable distribution of vaccines is essential: the rich world cannot be free of the threat of Covid-19 unless all countries have reached herd immunity by a combination of pre-existing immunities, infection and vaccination. Recreating a healthy rules-based international order that breaks down barriers to the free flow of masks, protective gear, test kits and pharmaceutical supplies would be a global public good.

Last April, Prime Minister Narendra Modi exhorted India to become ‘the global nerve centre of … multinational supply chains in the post Covid-19 world’. In his virtual address to the UN General Assembly on 26 September, Modi boasted that India’s pharmaceutical industry had sent essential medicines to more than 150 countries and promised: ‘India’s vaccine production and delivery capacity will be used to help all humanity in fighting this crisis.’

‘Sicken thy neighbour’ policies led dozens of countries to impose restrictions, including outright bans in some cases, on exports of critical medical supplies like masks, medicines, ventilators and disinfectants. Espousing nationalist rhetoric and policies, while abandoning international cooperation, aggravated the crisis. Governments can better protect the people they claim to represent by reversing the equation—ditching pandemic nationalism and embracing global cooperation instead.

Finally, albeit somewhat unfortunately, there’s also an element of schadenfreude in Indian circles that a developed Western country like Canada, whose do-gooder instinct often leads to irritating moralistic lectures on India’s perceived human rights failings, should see its Prime Minister Justin Trudeau phoning Modi on 10 February in a plea to boost vaccine supplies. Modi said India ‘would do its best to support Canada’s vaccination efforts’, but the request came too late to make the cut in India’s initial allocation of vaccines, subject to export restrictions because of the massive domestic need, to 25 countries.

As the global rollout of vaccines against Covid-19 gathers pace, there are already reports of a vibrant black market for the various vaccine candidates. A black market usually springs up fairly quickly when there’s a shortage of an item and people are prepared to pay substantial sums to obtain it. With Covid-19, there’s the added incentive for buyers of avoiding death or serious illness.

There are clearly the ingredients for a black market to thrive—the vaccines are being produced in large quantities, some supply chains are not secure, and some wealthy people will pay to jump the queue or obtain a preferred vaccine. This in turn will lead to corruption of those distributing and administering vaccines and those prepared to trade their priority place in the vaccination queue for money. The problem will be particularly acute in less developed countries.

The most profitable markets for black marketeers will be places where many people have died, vaccines are unavailable, and there is substantial corrupt wealth. Ukraine, for example, has registered more than 1.3 million Covid-19 infections and nearly 26,000 deaths in a population of 40 million. The Ukrainian government was slow to buy vaccines, hoping to get them free from the European Union, and has yet to launch its vaccination campaign. Ukraine is waiting for the delivery of 20 million vaccine doses from the Serum Institute of India and the global COVAX scheme, as well as vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech, Oxford/AstraZeneca and Novavax.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian police are investigating reports that some wealthy and influential Ukrainians were inoculated after paying up to $4,700 per dose, probably of the Pfizer vaccine. Reports suggest that the vaccine could have been brought in from Israel and that several top Ukrainian officials and business figures have been unofficially vaccinated.

If the vaccine has come from Israel, Israeli organised crime groups could be involved.

At least seven different Covid-19 vaccines are now being used around the world. The most desirable are the Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca vaccines. In the US, the Food and Drug Administration has approved emergency use of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, and UK regulators have approved all three. The WHO has approved the use of vaccines by Pfizer, AstraZeneca and the Serum Institute of India (Covishield), but it has not yet finalised approval of the Moderna vaccine.

In the US, there’s ongoing concern that people may try to manipulate the vaccination system at the state level in various ways—for example, by claiming essential-worker status, exaggerating their health risks, and using political influence or wealth to gain a vaccination advantage. There’s also a concern about vaccine theft.

The black-market price of the vaccine will be based not only on effectiveness and demand but also on ease of transportation and storage.

The most valuable are the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, which have shown 94% and 92% effectiveness, respectively, followed by the AstraZeneca vaccine with around 80% effectiveness. All supposedly require two doses, but the first dose of the Pfizer vaccine is 85% effective, according to a study in The Lancet medical journal, so a second dose may not be essential.

The initial cost of the vaccine is probably not a factor for black marketeers given the size of the potential profit margin. The AstraZeneca vaccine reportedly costs about $4.50 per dose, compared to Pfizer at $25 per dose and Moderna at around $47. (AstraZeneca says it’s not making a profit on the vaccine, while Pfizer and Moderna are discounting their prices for large orders.)

Logistically, the AstraZeneca vaccine would be easier for black marketeers to handle since it can be stored and transported at 4°C, while the Pfizer vaccine must be transported at –70°C. The Moderna vaccine may be stored between 2°C and 8°C for up to 30 days.

A shortage of any pharmaceutical soon leads to the production of fake items that can be passed off as the real thing. On the dark web, prices for Covid-19 vaccines seem to vary from a few hundred dollars to a few thousand. Many of the products are likely to be fakes.

In the US, Covid-19 scams have been widespread since the start of the pandemic, including more recently for access to vaccines. The FBI has warned of hackers, criminals and scam artists attempting to disrupt the vaccine supply chain or targeting vulnerable citizens.

In Australia, the Therapeutics Goods Administration is working closely with the Australian Border Force to prevent and detect the illegal importation and supply of vaccines. The TGA warns that it will take action against suspected illegal activity, noting: ‘Breaking the laws related to therapeutic goods in Australia can result in substantial penalties, fines or imprisonment.’

As the world bets on vaccines as a way out of the Covid-19 pandemic, vaccine candidates have quickly become a vehicle for national influence. China, Russia and India, for example, are each quick to publicly celebrate, through traditional media and official social media accounts, every new country that signs up to use their vaccines.

Stories are often promoted that emphasise the safety and affordability of countries’ vaccines. However, as vaccine-producing countries jostle for market share and political leverage for their products, some are prepared to resort to disruptive or deceptive tactics.

The battle over vaccine narratives has led to online influence and disinformation campaigns that aim to mislead or to amplify potentially negative news about rival vaccine candidates without proper context. Such behaviour could erode public trust and vaccine uptake, delaying global efforts to eradicate the disease and recover from the severe social, political and economic damage caused by the pandemic.

Russia reportedly went so far as to launch a covert disinformation campaign in 2020 designed to target and discredit the AstraZeneca/Oxford University vaccine. And already this year, both Chinese and Russian state media and official social media accounts have amplified unfavourable reporting about the Pfizer vaccine.

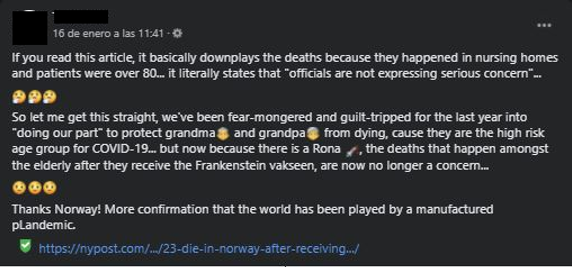

In early January, the Norwegian Medicines Agency reported that around 30 people died after receiving the Pfizer vaccine, most of whom were described as ‘frail’ nursing-home residents. While Pfizer is an American company, the vaccine was developed by an international team.

The news attracted considerable attention, including in Australia, where the government sought more information from Pfizer and Norwegian health authorities. It remains unclear ‘whether the reported deaths following COVID-19 vaccination are simply a function of age and declining health, or whether the vaccine may have played a role’, according to ABC News. The Norwegian Medicines Agency has since said there was not yet evidence of a direct link.

These reports were seized on by media in China and Russia, as well as by anti-vaccination influencers on social media. In addition to highlighting the deaths in Norway, one narrative pushed by state-linked media outlets focused on perceived double standards by Western media in their coverage of negative stories about their countries’ candidates. A 15 January editorial in the Global Times suggested that ‘major US and UK media were obviously downplaying’ the deaths.

Chinese and Russian vaccines have faced tough questions about their efficacy and the robustness and transparency of their testing regimes. In recent weeks, a Brazilian trial of a vaccine made by China’s Sinovac Biotech found that it was 50.4% effective at preventing symptomatic infections in ‘very mild’ cases, a lower success rate than was initially indicated.

Tweeting about the Norwegian Pfizer incident on 16 January, a reporter for China’s state-owned broadcaster CGTN asked whether any ‘major US or European media’ had picked up the story. ‘Not that I can see’, she wrote. ‘Imagine if 13 people are assessed to have died from Chinese-made #vaccines, it would have made headlines EVERYWHERE!’

The same day, she tweeted two screenshots of headlines about potential Pfizer vaccine-linked deaths in Germany. Without context—10 older people reportedly died out of an estimated 800,000 Germans vaccinated—the screenshots paint a frightening picture of the vaccine’s potential side effects.

Both tweets were retweeted by Zhao Lijian, a spokesperson for China’s foreign ministry, who has more than 877,000 followers.

On Facebook, the 15 January Global Times story received at least 7,200 interactions on public posts, according to the social monitoring platform Crowdtangle. It was shared by the verified account of French politician François Asselineau, which received the most Facebook interactions, followed by his party page, Union Populaire Républicaine.

Another story on 19 January said Chinese health experts were advising Australia to halt approval for the Pfizer vaccine following the deaths in Norway. ‘Australia should broaden its choices of COVID-19 vaccines, such as purchasing Chinese-produced inactivated vaccines’, the article said.

The claimed lack of Western media coverage of alleged Pfizer vaccine-related deaths was also echoed by Russian state-linked social media accounts and outlets. Sputnik News ran a story claiming, ‘Despite numerous signs of the Pfizer vaccine having side effects, the American shot has not received that much scrutiny in the mainstream media.’

The Twitter account linked to Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine, @sputnikvaccine, shared the Global Times opinion piece, commenting, ‘A view from China on vaccine politics and double standards of media coverage’, as well as other reporting about the Norway incident. Since late 2020, the account has tweeted news coverage highlighting the price of the Pfizer vaccine compared with Sputnik V and the risk of allergic reactions to the Pfizer vaccine.

Russia Today has also reported on Pfizer side effects that have not been confirmed as definitively linked to Covid-19 immunisation. For example, a link to a story in Russia Today about one woman’s potential yet unconfirmed side effects received more than 11,000 interactions in the form of reactions, comments and shares on Facebook, according to Crowdtangle, and was shared by a number of prominent anti-vaccination influencers.

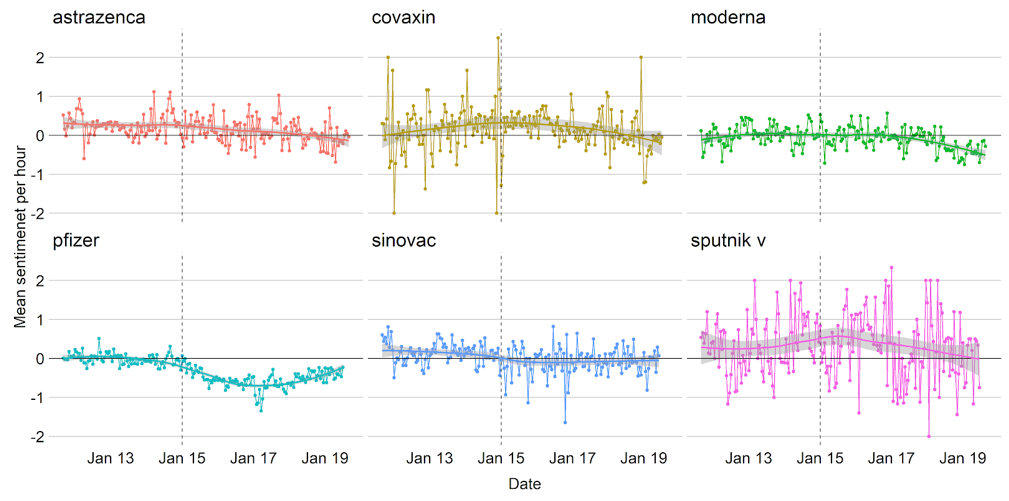

Our analysis of 455,940 tweets mentioning vaccine-related terms between 11 January and 19 January found an overall shift towards negative sentiment on vaccines following the Norwegian Medicines Agency report. This suggests that negative portrayals of one vaccine might erode public trust in all vaccination programs.

Tweets mentioning ‘pfizer’ had the greatest relative increase in negative sentiment across the eight-day period. Sputnik V and Covaxin both also had highly variable sentiments reflecting polarising debates over each vaccine on Twitter. In the graphic below, positive and negative numbers represent degrees of positive and negative sentiments.

The amplification of stories about vaccine side effects or deaths that are not definitively linked to immunisation without proper context has the potential to undermine public health and may be seized upon by the anti-vaccination community.

A number of anti-vaccination influencers also jumped on the Pfizer story. Similar to the CGTN reporter’s tweet about Pfizer, some users posted screenshots of media headlines that could cause fear when presented without context on social media networks such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

News outlets must take particular care with their headlines, recognising how they can be displayed in screenshots and posted on social media to serve particular agendas. As CNN has reported, headlines without proper context create ‘the risk that people see only that there have been fatalities and get the false impression coronavirus vaccines are dangerous’.

Proper scrutiny of all Covid-19 vaccines is essential to ensure public trust and safety. And as vaccination programs roll out around the world, reporting about allergic reactions and deaths will continue—even when a clear link with a recent inoculation has not been established. If nations continue to deliberately amplify such stories without proper care, it could have a dangerous impact both on vaccine uptake and trust in the public health agencies tasked to deal with ending the pandemic.

Covid-19 is a gritty and primitive specimen—so primitive that scientists dispute whether it qualifies as a form of life. But it is wickedly contagious and possessed of fiendishly advanced stealth capabilities.

The pandemic erased ‘normality’ across most of our planet, effortlessly riding the tentacles of globalisation to every corner of the world, paying no greater heed to geopolitical divides than to religious, racial or political boundaries.

Separation and lockdown became the global norm. The pandemic gradually reduced the distracting cacophony of the international system to a whisper, leaving all states unusually exposed. This inadvertent additional transparency intensified the inflammatory effect the virus had on a number of international relationships.

The scale of the economic penalty paid to weather the pandemic has been immense—essentially immeasurable—as are the social, political and other changes tangled up with this huge scar on humanity’s timeline. The world will feel and work differently when Covid-19 is behind us.

In one decisively important sense, the pandemic has been a transformational watershed: its impact on the character of the US–China relationship. China and the United States have been prepared to see their difficult bilateral relationship fracture precipitously and be effectively stripped of every residual positive attribute.

Far from rekindling suppressed instincts of collegiality, the crisis saw the two premier states defiantly flaunting the distinctive features of their governmental systems. Beijing and Washington engaged in a bitter and emotional exchange on the causes, management and probable effects of the pandemic. The consequences of this emotional divorce—if it is simply allowed to run its course—are incalculable.

A critical element of this estrangement was a mutual impatience to be rid of the deep economic entanglements that had developed over the decades of engagement.

Among the more confident predictions of new or strengthened propensities post-Covid was the winding back of globalisation: to restrain or qualify the post–Cold War willingness to allow market forces free rein to determine the supply chain for all products.

As major-power relations deteriorated in the new century, some began to question the wisdom of this philosophy, at least for products deemed highly sensitive for national security or health. Many consider that while efficiency may have been king in the past, the Covid experience will see it displaced for an indeterminate period by resilience.

Economists, of course, have warned that market dynamics and the profit motive constitute formidable forces that can only be diverted at considerable cost to the state and/or the consumer. There are also important wider considerations.

International trade, joint ventures and reciprocal direct investment are self-evidently a crucial medium for developing common interests between states, including a shared resistance to issues that generate tension and confrontation and put those common interests at risk. This belief—that economic interdependence strengthens the peace between states—has long been part of the enduring drive for genuinely freer international trade. It’s an aspect of our world that we jettison to our peril.

Economic interdependence may not guarantee peace, as the events of August 1914 attest, but it can still prove invaluable.

An illuminating indicator of the intensity of the political clash between the US and China that the pandemic brought to a head is what happened to the rules-based order. That order—which had developed from the foundations laid by the US in the immediate aftermath of World War II—had been flagged as an issue for most of the new century.

Most states were prepared to concede, albeit discretely, that the prevailing order had been instrumental in the strong improvement in their international standing and future opportunities. But a few also signalled reservations because that they had not participated in its design.

The US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 without a clear mandate from the UN Security Council damaged the aura of authority and acceptance associated with the order. The issue surged to a new plateau over the manner in which Crimea was reincorporated into the Russian Federation in 2014 and China’s dramatic construction of artificial islands in the South China Sea in 2014–15, developments that put stress on central components of the order: the UN Charter and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea.

The stresses of the pandemic disquiet distilled into the contention that alternatives to liberal democracy were available that were more effective and offered a superior basis for a revamped set of norms and guidelines to underpin international order.

A core axis of resentment about the prevailing order has been exposed as the perceived contention that liberal democracy and the market economy was and remained an evolutionary pinnacle in humanity’s aspiration to devise the optimal system of governance.

A cluster of states—the strongest of which is China—increasingly contend that, over the very long periods of time that they have been coherent communities, they have evolved distinctive social contracts and means of giving effect to such contracts. These arrangements—and associated notions of such core themes as democracy, human rights and the rule of law—may in some respects differ quite sharply from the liberal democracy model.

But these states now insist that it is unacceptable to in any way question their legitimacy or to portray them as having anything other than equivalent status.

In an address to the Institute of International and Strategic Studies at Peking University in April 2020, China’s foreign minister elected to put it in the following terms: ‘China and the US are facing increasingly prominent contradictions in social systems, values and state interests.’

While openness and clarity about a contentious issue is an important step forward, it does not promise a durable solution. That is almost certainly the case here.

Among the foundational principles that were drawn from the history of the first half of the 20th century and that informed the US approach to order is that the concentration of power was a threat to the primacy of the individual and to international peace because errors of judgement could be more directly translated into massive and irreversible actions.

The solution was deemed to lie in deliberate disaggregation and institutionalised power-sharing. The democracy/market economy model was not intended or expected to deliver the most efficient and effective governance. Rather, the objective was to provide the strongest governance consistent with the state being subordinate to its citizens.

In contrast, the thinking that animates China’s leadership—from the writings of Confucius to Marx, Lenin and Mao—points to the state taking comprehensive responsibility for the nation’s destiny, insisting on correspondingly exclusive ownership of the instruments of power and recasting the concepts of rights, obligations and rewards in collective rather than individual terms.

At the practical level, these somewhat esoteric notions translate into sharp differences in the role of the state in business affairs. That, in turn, gives rise to concerns that these differences preclude a level playing field or fair competition for national and foreign markets.

The body of rules seeking to provide a level playing field for international commerce and related matters such as the protection of intellectual property and market access—or a system to ensure fair competition between private enterprises from all nations—are without doubt the most widely and continuously accessed component of the rules-based order. These were roughly the issues that defeated US–China negotiations in 2018–19.

This development does not fundamentally challenge the importance of a rules-based order, but it does leave hanging whether it is possible to envisage an order that is devoid of a normative foundation.

In a year when Australian and other parts of the world have been battered by savage storms, intense bushfires, a pandemic or a combination of all three, it’s time to rethink how we approach threats to our national security.

The warning is delivered by West Australian Labor MP Anne Aly in the third volume of ASPI’s After Covid-19 series edited by Genevieve Feely and Peter Jennings.

Aly notes that the past decade has demonstrated that contemporary threats to our security and wellbeing come from unconventional sources in a landscape that’s much more complex and multidimensional, and much less predictable.

She writes that it’s 75 years since the end of World War II but, where conflict has endured, that milestone will have warranted little more than a passing nod—‘or perhaps a cynical sigh’.

‘In other parts of the world, consumed by the Covid-19 pandemic, the anniversary might give us pause to reflect on the changing landscape of international and national security’, she says.

For Australians, the year began with the bushfires blistering through the nation’s heart. A grieving population assessed the damage, dusted itself off and drew on strength and compassion to recover. Then the pandemic swept through China, Europe, Asia, North America and Australia.

Covid didn’t respect borders, form an orderly queue or discriminate, says Aly. ‘It can’t be shot at, bombed, arrested, turned back or sent home. Our front line of defence doesn’t wear army fatigues and carry a gun but is made up of ordinary Australians—hospital staff, nurses, retail workers, security guards, childcare workers, teachers and police.’

She says the ‘traditional’ hard strategies involving military force, policing, intelligence and legislation have proved insufficient for ensuring long-term security. They should be combined with soft power to respond to the root causes of issues such as violent extremism by considering social, economic, political and historical contexts.

In this diverse collection of political views, House of Representatives Speaker Tony Smith describes how Australia’s parliament adapted to the pandemic with new rules and practices. The institution proved resilient, and practical changes were adopted with bipartisan agreement and the use of technology.

For the first time, MPs took part in some parliamentary proceedings remotely, says Smith. The fact that proceedings were already broadcast via the internet, radio and television meant that Australians could observe the work of the House even when public access to the chamber was suspended.

Greens senator for WA Jordon Steele-John says the pandemic exposed fault lines in systems and flaws in approaches to problem-solving. It’s shone a light on the fragility of our economy in the face of external pressures, exacerbated global tensions and set the scene for an explosion of economic inequality.

We’ve arrived at a crossroads, Steele-John says. Do we continue to spend billions on military technology and further exacerbate global tensions, or invest in solutions to the real health and environmental challenges we’re all facing and focus on fostering global cooperation and conflict resolution to address people’s needs in a post-Covid world?’

Steele-John says billions are wasted on military posturing while real needs in Australia and the region are ignored. ‘It’s this type of tired, hawkish thinking that’s taking focus away from understanding, and prioritising, the real challenges before us and for which we can effectively plan’, he says.

‘The reality of our time is that we’re living in an age of climate crisis and accelerated ecological collapse. Right now—not in some distant future—climate change is putting the things that we care about at risk.’

New South Wales Liberal senator Jim Molan writes that Australia faces two challenges, Covid-19 and its deteriorating strategic environment, and it needs a national security strategy to manage both.

Molan says Covid has created an acceptance of change while the strategic situation has been recognised and key countermeasures have been initiated in defence, foreign interference, manufacturing and cybersecurity.

He says Australia has achieved great things as a liberal democracy, but it’s been rich and secure enough to hide imperfections and inefficiencies. ‘That era has finished’, he says. ‘To just re-establish the nation that we were before the pandemic wouldn’t be a triumph or even an achievement. It would be a lost opportunity, a tragedy, and possibly an existential one.

‘We have an obligation to turn the post-Covid period into Australia’s renaissance though vision, policies and strategies that create a self-reliant, prosperous, sovereign nation at no permanent cost to our real freedoms.’

Victorian Labor senator Kim Carr says there’ll be no return to normal when the pandemic recedes. Ways of thinking that dominated past policymaking are no longer tenable, he says. ‘The pandemic has comprehensively demonstrated the failure of neoliberal economics.’

That was, says Carr, a vision of Australia as essentially a farm, a quarry and a beach, but not a place where people make things.

Australians found that initially the nation couldn’t produce enough personal protective equipment for healthcare workers or enough ventilators for intensive care units in hospitals.

Carr says the government has accepted that Australia needs a thriving manufacturing sector if it’s to avoid such a crisis again.

Some kinds of manufacturing, such as steel, aluminium, cement, chemicals and plastics, are strategically vital, he says. ‘And, because those heavy industries are big energy consumers, the question of how to revive manufacturing can’t be separated from the question of how to provide reliable supplies of affordable energy while also meeting our international obligations on climate change.

‘It’s only by building sovereign capabilities in manufacturing that we can diversify Australia’s economic base and thereby reduce our exposure to the impact of global downturns and our excessive dependence on certain markets, most notably China.’

South Australian Liberal senator David Fawcett says Covid-19 has brought supply-chain integrity into stark focus and exposed vulnerabilities in commercial practices which often rely on components imported ‘just in time’. Disruption in supply can undermine Australia’s ability to function as a first-world nation.

The current federal approach to procurement can’t be relied on to deliver value for money in critical areas when under stress, says Fawcett, and the nation must ask three vital questions:

The answers will make Australia more resilient and capable of responding independently to threats or crises, Fawcett says.

Greens leader Adam Bandt writes that in successfully responding to the pandemic, Australian governments did unexpected things. ‘Governments put scientists ahead of vested interests. The wellbeing of Australia’s peoples was put ahead of a budget surplus. The public healthcare system was exalted’, he says.

Covid-19 also exposed neoliberalism’s frailties, says Bandt, shown in the exclusion of casual workers from the JobKeeper wage subsidy, the use private contractors to run hotel quarantine, the failure to regulate for-profit aged care, and a market-driven approach to housing supply that allowed public housing to be treated as a low-quality, residual solution for people in need.

Australia, like most of the rest of the developed world, also stumbled in the early days of Covid-19 because it hadn’t heeded the advice of scientists and hadn’t adequately prepared for a pandemic, says Bandt.

‘The lessons here are clear’ he says. ‘We must put science at the centre of policymaking at the same time as we put care at the centre of political strategy. We must do this not just to prepare for the next pandemic but because the next emergency that scientists are warning us of is already here, threatening our health, our security and our species’ very existence. For all the deprivations brought about by Covid-19, they pale beside the looming impacts of the climate crisis.’

Apocalyptic works of fiction, like Stephen King’s The stand and Wolfgang Petersen’s Outbreak, have a relatively standard script for pandemics. Think an initially small-scale mystery illness identified by a weary doctor. Cue the scene where a roomful of government officials exhale sharply as a map simulation shows an exponentially increasing number of infections, marked by red dots. There is a depressing similarity between this narrative and what we’ve been experiencing in 2020.

Of course, we’ve been lucky enough to avoid the fall of humankind, and zombies. However, we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that, while there are promising vaccines in development, there’s no miracle cure yet.

In 2018, two years before Covid-19 emerged, global health expert Jonathan Quick, in his book The end of epidemics, wrote the script for this latest pandemic. He warned the world that ‘denial, complacency and hubris’ might stand in the way of our preparation for a novel virus. And for the most part it did, including here in Australia.

Covid-19, despite its devastating health, social and economic costs, hasn’t been an apocalyptic event. It has, however, been a defining moment in our national understanding of the risk of pandemics.

This global crisis has shown us, especially during the first few months of 2020, that Australia may not be as resilient as we had once hoped. I’m not referring to toilet paper here, but to our medical countermeasure preparedness: everything from the ability to manufacture personal protective equipment to researching vaccines.

For most Australians, 2020 has shown us that national investments in medical countermeasures are a wise insurance policy.

The risk of another global pandemic emerging has not changed since January. The likelihood and consequences of a similar event occurring tomorrow remain the same. However, for the time being, our intellectual and emotional understanding of that risk has evolved.

Before Covid-19, the Australian government knew the potential risks of a pandemic. And it had advance knowledge of the vulnerabilities in our preparedness.

In 2012 and 2017, the Defence Science and Technology Group led audits of Australia’s capabilities in medical countermeasures (MCM). These reviews allowed the departments of Defence, Health, Industry, and Foreign Affairs and Trade to assess Australia’s MCM capacity for product development and deployment.

The 2017 audit found that Australia had a dispersed and relatively small but experienced community with expertise relevant to MCM product development, including vaccines, therapeutics, diagnostics and devices.

Unfortunately, those responsible for our MCM faced several enduring challenges. Our MCM product development capability, in many instances, lacked the critical mass necessary to be effective. And the capability we did have wasn’t vertically integrated in a way that would support onshore end-to-end product development.

The 2017 report revealed an acute shortage of appropriate expertise in product development, manufacturing, regulatory science, translational medicine, toxicology, clinical pharmacology and project management. And there was a lack of appropriate national training programs to develop this expertise.

Of more significant concern, and as we’ve learned during the Covid-19 pandemic, Australia had limited facilities suitable for manufacturing MCM products.

Critically, these audits led to the establishment of the national MCM initiative at DMTC (formerly the Defence Materials Technology Centre), which aimed to support informed recommendations for MCM investment. However, investment was slow, and Covid-19 found Australia wanting in MCM preparedness and still highly dependent on overseas supply chains.

The next audit wasn’t due to be conducted until 2022. However, Covid-19 highlighted an urgent need for it to be brought forward with an expanded scope beyond MCM to include personal protective equipment, modelling and simulation, medical devices, hazard management and sensing systems. This audit is to be completed by mid-2021.

The audit, known as the ‘national health security resilience assessment’, will be conducted using an integrated and secure digital platform. This system allows for real-time updates and will enable government stakeholders to visualise Australian expertise and capacity to respond to a range of emerging threats.

Importantly, this time around the review will dig much deeper into our national preparedness. It’ll examine the capacity of the Australian research and development sector to manufacture and distribute priority products and solutions that can build sovereign resilience.

The audit will need to carefully consider Covid-19’s lessons, including the impacts of cascading risks. This broader approach will allow policymakers to identify how the sector has matured in response to a range of threats, including pandemics, and where future investment may need to be focused.

With our newfound national awareness of pandemic risk, this audit is well timed. For it to be a success, though, everyone—whether in the private, public or not-for-profit sector—needs to get involved. It’ll also be critical for those carrying out the assessment to approach the task with a fresh perspective and a willingness to respond decisively.

Think tanks and key leaders from around the world will meet in a massive online event this week to search for ways to reset history in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

On Friday 20 November, ASPI will take part in the ‘Global Town Hall’, a set of moderated discussions on foreign and security policy matters with a strong focus on the Indo-Pacific region.

It will take in the pandemic, the implications of climate change and cooperative measures that might head off disaster, and the impact of nationalism and populism, and examine the likely role of the United States under Joe Biden and in the fallout from Donald Trump’s reign.

ASPI’s executive director, Peter Jennings, spoke with Dr Dino Patti Djalal, a veteran Indonesian diplomat and the founding director of the Foreign Policy Community of Indonesia think tank, which initiated the discussions.

Jennings observes that out of the Covid catastrophe has come opportunities for such discussions and it has proven easier to get key people together online than it was before the pandemic when speakers flew around the world to conferences.

‘I think it’s a great idea and in particular I’m intrigued with the idea of tracing the clock of the globe as we go around the world with different think tanks handing over to counterpart think tanks’, says Jennings.

Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo will make the scene-setting keynote address.

Australian participants include Foreign Minister Marise Payne and former prime minister Kevin Rudd. The foreign ministers of Indonesia, China and Russia will speak.

Djalal says the world is facing one of the greatest crises in modern history and notes hopefully that crises usually lead to change.

‘We want to examine how we guide and work for that change to ensure that we don’t return to the world as it was but that we have a stronger and better world’, he says.

Djalal will open proceedings with a session examining how 2020 has been so different to previous years and anticipating what will happen in the next year or two.

This opportunity for a ‘great social reset’ will be discussed by Payne, former East Timorese president José Ramos-Horta, Malaysian MP Nurul Izzah Anwar and the Reverend Kyoichi Sugino, deputy secretary general of Religions for Peace, an international coalition of religions seeking an end to violence.

India’s External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar will be keynote speaker in a session on ‘The Indo-Pacific and the Covid-19 crisis: What are the next steps?’

Jennings will be a panellist with former permanent secretary in Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs Bilahari Kausikan; Professor Richard Heydarian, a non-resident fellow at Stratbase ADR Institute; and Dr Ruan Zongze, executive vice president and senior fellow at the China Institute of International Studies.

Rudd will be a panellist in a session titled ‘Geopolitical reset: Is a world of more cooperation, less rivalry possible?’ The keynote speaker for the session will be Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi.

Other panellists will be former Indonesian foreign minister Marty Natalegawa and Professor Kishore Mahbubani, distinguished fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Asia Research Institute.

They’ll search for ways to build a just, equitable and harmonious global society. ‘And if there is going to be a geopolitical reset, what will it look like?’, asks Djalal. ‘What impact will Biden have as US president?’ And what happens to nationalism and populism during the time of Covid as leaders come under pressure to deliver rather than being able to play the demagogue?

Another session will examine the need to provide the people of the world with equal access to Covid-19 vaccines when they become available and, asks Djalal, ‘is that realistic, or utopia?’

The likely consequences of climate change will figure strongly. ‘I do believe that as we aim for economic rebound, it should not just be about achieving normal growth but it should be about achieving a decarbonised economy’, Djalal says.

The final session will be on ‘Welcome back, America’ with, says Djalal, ‘a big question mark’.

‘We are yet to see how President-elect Joe Biden will return America to activism and leadership, which we all hope, of course.’

For more information and to register for the Global Town Hall, click here.

In mid-September, Jakarta governor Anies Baswedan reinstated a partial lockdown in a bid to prevent the Indonesian capital’s hospitals from being overwhelmed. With nearly 12,000 active cases of Covid-19 in the city, ICU beds were projected to reach full capacity within six days.

The lockdown was moderate by international standards. People were required to remain at home, work from home if possible and wear masks when outside. Schools were closed and lessons were conducted online, and 11 essential sectors, including public markets and transport, were permitted to operate at a reduced capacity.

But contradictory lockdown regulations and disciplinary procedures by local and central governments left many people confused or unwilling to comply.

On 15 October, after a steady drop in case numbers, Baswedan announced that some of the restrictions on Jakarta’s residents and businesses would be gradually relaxed. These reduced measures may be insufficient, considering the pandemic’s pressure on Indonesia’s already vulnerable healthcare system. The isolation and ICU wards in Jakarta’s Covid referral hospitals were around 65% full at the time of the announcement.

Indonesia’s national health scheme, Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional (JKN), is nevertheless an impressive program both in ambition and reach. Initiated in 2013 by President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s government, the JKN aims to provide affordable, comprehensive health and dental care to over 221 million Indonesians. With around 96 million low-income earners accessing treatment at no cost, the JKN has transformed Indonesian healthcare from a luxury expense to a widely accessible service.

Primary healthcare is provided through thousands of small community health centres known as Puskesmas, from which patients can be referred to hospitals for secondary and tertiary treatment. However, the standard of healthcare varies, and some regional areas lack services provided in urban centres.

Structurally, the JKN is comparable to England’s National Health Service. It’s a state-run health organisation funded by both government and some patient contributions, which operates at a deficit.

But, even before Covid, the sheer number of non-contributing patients in Indonesia made the program financially unsustainable. Only around 8% of healthcare recipients are paying members. There’s no mechanism to collect outstanding payments, and it’s estimated that 40% of booked contributions remain unpaid. Recently the JKN has required significant government bailouts, sparking public discussion on whether low-income Indonesians should start paying monthly fees.

When Covid emerged, the JKN was financially compromised and vulnerable. Gadjah Mada University epidemiologist Riris Andono warned, ‘It’s not good. We are not prepared.’ He described shortages of intensive care facilities, personal protective equipment and other crucial equipment, including ventilators.

Some members of the international community have stepped up. China has donated several tonnes of PPE and Covid testing equipment. In May, Japan delivered 12,200 Avigan influenza tablets to Indonesia to mark the two nations’ cooperation in the fight against Covid.

Australia donated US$4.2 million in June through the World Health Organization to strengthen Indonesia’s laboratories and help protect patients and workers at health facilities. New Zealand committed NZ$5 million to UNICEF towards Indonesia’s Covid response.

Indonesian officials have been reassuring the public that inequalities in the health system won’t hinder or delay access to a Covid-19 vaccine once one is available. The chair of Indonesia’s Covid Taskforce described Indonesia’s approach to vaccine negotiations as ‘aggressive’, noting it has ‘already secured the vaccines from several partners’.

In September, Indonesia renewed its agreement with UNICEF, safeguarding the nation’s access to potential vaccines for Covid-19 and other illnesses far below the likely market price, and ensuring affordable national distribution.

Indonesia has welcomed international collaboration in vaccine research. Its Bio Farma pharmaceutical company is trialling a vaccine locally in Bandung with China’s Sinovac Biotech, using Indonesian volunteers. Mayor of West Java Ridwan Kamil went so far as to suggest that government officials should volunteer for the trial.

Alongside Sinovac Biotech, China’s Sinopharm and CanSino have pledged to supply their Covid vaccines to Indonesia. All three companies are aiming to begin delivery in November. To further ‘accelerate’ its vaccine access, Indonesia recently sent a team of officials to China to carry out inspections at each of the companies.

The November timelines are both ambitious and optimistic, particularly given that all three companies are still conducting clinical trials.

So, how will Indonesia’s healthcare system fare in the interim?

Indonesia lacked sufficient medical staff prior to Covid, with only 0.2 general practitioners and 1.4 nurses per 1,000 people in 2019. Trainees are overseeing Covid testing to free up health workers in hospitals, but high infection rates and unrelenting demand are taking a huge toll.

Death rates for healthcare workers are among the highest globally. By mid-September, Indonesia had already lost 115 doctors and at least 82 nurses, and thousands more have contracted the virus, forcing health facilities to close.

High community transmission among civilians and healthcare workers, low rates of testing and overwhelmed health facilities are being met with only moderately strict and inconsistent lockdown regimes. This puts patients at risk and significantly restricts the health care that the system can provide.

The pandemic has exposed key vulnerabilities in Indonesia’s health security and sharpened calls for reform.

US management consultants McKinsey & Company has said that if these vulnerabilities are met with policy changes, structural and financial reform, and a renewed focus on personnel training and supply chains, Indonesia could emerge with much stronger health security in the long term.

But in the meantime, the toll is rising. While government rhetoric focuses on a hypothetical vaccine, the healthcare sector needs more attention now.

When the Jewish new year began late last month, Israel was enduring its second nationwide lockdown, after daily per capita Covid-19 infection and death rates reached some of the world’s highest levels. How did a country with practically closed external borders, sophisticated technological and institutional capacities, a high-quality and efficient health-care system, and a culture of solidarity in wartime fail so spectacularly at addressing the pandemic?

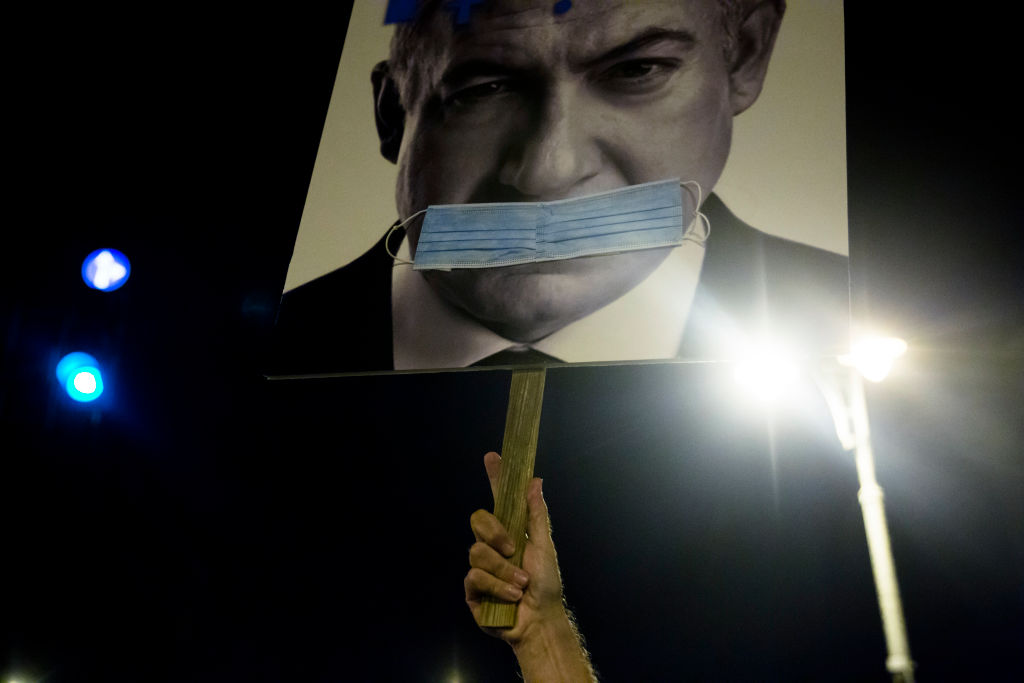

Although long years of neoliberal economics have certainly taken their toll on the country’s welfare system, the answer lies elsewhere. Partly, it is Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s deceitful, divisive approach to managing the crisis—and to governing more generally—that has been laid bare. But, more fundamentally, Israel’s pandemic failure reflects the deeply fragmented society and dysfunctional political system of which Netanyahu has taken advantage throughout his career.

The virus has exposed Israel as a polarised federation, whose various tribes put their sectarian interests ahead of the common good. The ultra-Orthodox community, for example, has sought to exercise its autonomy above all—and it has paid the price, with the country’s highest Covid-19 infection rates. Though this community comprises only about 12% of Israel’s population, it accounts for about half of all infected people over 65 and under 18. Until recently, Israel’s Arab community—21% of the population—did not lag far behind.

But Israel’s minorities do not have a monopoly on the defiance of norms. Breaking conventions, an innate lack of discipline, and disregard for authority—the very traits to which some experts attribute the country’s extraordinary creativity as a ‘start-up nation’—are national hallmarks. Netanyahu and his ministers who were caught violating the precautionary rules they had imposed on the country reflect a broader phenomenon; the government hasn’t exactly been a role model for the unruly public.

Netanyahu has built his career on stoking sectarian divisions. In contrast to French President Emmanuel Macron, who has now launched a campaign against ‘Islamist separatism’ in France, Netanyahu has thrived on a rapidly escalating Kulturkampf. In particular, he has formed a corrupt coalition with the ultra-Orthodox community, whose political support he has bought with the labour and sacrifice of other segments of society.

For starters, he actively encourages the unproductive, burdensome lifestyle of the ultra-Orthodox, who have staggeringly high fertility rates (averaging 7.1 children per woman, compared to 3.1 overall). Moreover, barely half of ultra-Orthodox men participate in the labour market. And the community includes about 135,000 yeshiva students, who refuse military service and study only scripture—an education that leaves them unfit for modern life.

Who pays for this lifestyle? Israel’s dynamic, secular middle class, which produces much of the country’s wealth, carries the burden of military service and accounts for a large share of the government’s tax revenues.

Now, the pandemic is compounding these costs. Rather than heeding expert advice and imposing targeted lockdowns on hard-hit communities—such as the ultra-Orthodox—Netanyahu chose nationwide measures, punishing the groups that make Israel’s economy run to avoid targeting a key constituency. The entire country is effectively a hostage to political expediency.

But Netanyahu’s motivation for imposing another lockdown extends well beyond mollifying the ultra-Orthodox community. His corruption trial, which has already been delayed by his lawyers’ obstructive tactics, will resume in January. Netanyahu would eschew no dirty trick to disrupt the proceedings, which threaten to keep his bribery and corruption scandals, and questions about his fitness to lead, in the national consciousness.

Netanyahu’s anti-corruption trial is also a key motive for his repeated thwarting of an agreement on a new budget. As long as there is no agreement, there will be regular opportunities to dissolve parliament and hold new elections, an outcome that might finally enable Netanyahu to form a coalition willing to bar the indictment of a serving prime minister.

To be sure, in late August, Netanyahu agreed to a 100-day extension with his coalition partner, the Blue and White party’s Benny Gantz, narrowly avoiding Israel’s fourth election in two years. But that probably reflects the fact that opinion polls indicate a sharp decline in support for Netanyahu’s Likud party. Netanyahu probably hopes that this will change by the time the next budget deadline arrives.

In the meantime, he is hoping to change the conversation, not by providing real leadership, but by stifling dissent. He has been using the Covid-19 crisis as a pretext for conducting China-style digital surveillance and sharply limiting the freedom to protest.

Mass demonstrations over Netanyahu’s alleged corruption and the government’s handling of the pandemic have been raging for months. To get protesters off the streets—and out of the news—Netanyahu backed a rule banning protesters from holding demonstrations more than one kilometre from their place of residence, under the guise of stopping the spread of Covid-19. The measure was also aimed at appeasing his Orthodox allies, as it created a false symmetry between the ban on protests in open spaces (where the risk of infection is minimal) and the restriction of prayers in synagogues (known infection hotspots).

But the move backfired. Unable to participate in the single localised protest in front of the prime minister’s Jerusalem residence, demonstrators began protesting close to home—all across the country.

This nationwide display of popular rage is also a model of creative, orderly civic resistance. The array of groups leading the charge—with names such as ‘Black Flag’ and ‘Crime Minister’—largely comprise young, educated and conscientious Israelis and many self-employed workers facing severe economic hardship. They are unlikely to give up easily, despite Netanyahu’s best efforts.

But while Netanyahu’s narcissistic leadership demands resistance, the upheaval in Israel carries significant risks. Israel is besieged not only by a deadly virus, but by identity politics, sectarian strife and dishonest leadership. As the economic consequences of lockdown multiply, social and political tensions will only rise. As President Reuven Rivlin noted ominously last week, ‘the air is full of gunpowder’.

There is no single future until it happens, and any effort to envision geopolitics in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic must include a range of possible futures. I suggest five plausible futures in 2030, but obviously others can be imagined.

The end of the globalised liberal order. The world order established by the United States after World War II created a framework of institutions that led to a remarkable liberalisation of international trade and finance. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, this order was being challenged by the rise of China and the growth of populism in Western democracies. China has benefited from the order, but as its strategic weight grows, it increasingly insists on setting standards and rules. The US resists, institutions atrophy and appeals to sovereignty increase. The US remains outside the World Health Organization and the Paris climate agreement. Covid-19 contributes to the probability of this scenario by weakening the US ‘system manager’.

A 1930s-like authoritarian challenge. Mass unemployment, increased inequality and community disruption from pandemic-related economic changes create hospitable conditions for authoritarian politics. There is no shortage of political entrepreneurs willing to use nationalist populism to gain power. Nativism and protectionism increase. Tariffs and quotas on goods and people increase, and immigrants and refugees become scapegoats. Authoritarian states seek to consolidate regional spheres of interest, and various types of interventions increase the risk of violent conflict. Some of these trends were visible before 2020, but weak prospects for economic recovery, owing to the failure to cope with the Covid-19 pandemic increase the probability of this scenario.

A China-dominated world order. As China masters the pandemic, the economic distance between it and other major powers changes dramatically. China’s economy surpasses that of a declining US by the mid-2020s and China widens its lead over one-time potential contenders like India and Brazil. In its diplomatic marriage of convenience with Russia, China increasingly becomes the senior partner.

Not surprisingly, China demands respect and obeisance in accordance with its increasing power. The Belt and Road Initiative is used to influence not just neighbours but partners in places as distant as Europe and Latin America. Votes against China in international institutions become too costly, as they jeopardise Chinese aid or investment, as well as access to the world’s largest market. With Western economies having been weakened relative to China by the pandemic, its government and major companies are able to reshape institutions and set standards to their liking.

A green international agenda. Not all futures are negative. Public opinion in many democracies is beginning to place a higher priority on climate change and environmental conservation. Some governments and companies are re-organising to deal with such issues. Even before Covid-19, one could foresee an international agenda in 2030 defined by countries’ focus on green issues. By highlighting the links between human and planetary health, the pandemic accelerates adoption of this agenda.

For example, the US public notices that spending $700 billion on defence did not prevent Covid-19 from killing more Americans than died in all its wars after 1945. In a changed domestic political environment, a US president introduces a ‘Covid Marshall Plan’ to provide prompt access to vaccines for poor countries and to strengthen the capacity of their healthcare systems. The Marshall Plan of 1948 was in America’s self-interest and simultaneously in the interest of others, and had a profound effect on shaping the geopolitics of the ensuing decade. Such leadership enhanced US soft power. By 2030, a green agenda has become good domestic politics, with a similarly significant geopolitical effect.

More of the same. In 2030, Covid-19 looks just as unpleasant as the influenza pandemic of 1918–20 looked from 1930 and with similar, limited long-term geopolitical effects. Prior conditions persist. But, along with growing Chinese power, domestic populism and polarisation in the West, and more authoritarian regimes, there is still some degree of economic globalisation and a growing awareness of the importance of environmental globalisation, underpinned by a grudging recognition that no country can solve such problems acting alone.

The US and China manage to cooperate on pandemics and climate change, even as they compete on other issues such as navigation restrictions in the South or East China Seas. Friendship is limited, but rivalry is managed. Some institutions wither, others are repaired and still others are invented. The United States remains the largest power, but without the degree of influence it had in the past.

Each of the first four scenarios has about one chance in 10 of approximating the future in 2030. In other words, the chances are less than half that the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic will profoundly reshape geopolitics by 2030. Several factors could alter these probabilities. For example, the rapid development of effective, reliable and cheap vaccines that are widely distributed internationally would enhance the probability of continuity and reduce the probability of the authoritarian or Chinese scenarios.

But if US President Donald Trump’s re-election weakens America’s alliances and international institutions, or damages democracy at home, the probability of the continuity scenario or the green scenario would decrease. On the other hand, if the European Union, which was initially weakened by the pandemic, succeeds in sharing the costs of member states’ response, it could become an important international actor capable of increasing the likelihood of the green scenario.

Other influences are possible, and Covid-19 may produce important domestic changes related to inequalities in healthcare and education, as well as spurring the creation of better institutional arrangements to prepare for the next pandemic. Estimating the long-term effect of the current pandemic is not an exact prediction of the future, but an exercise in weighing probabilities and adjusting current policies.