Germany’s homegrown Q menace

On 1 August 2020, about 30,000 people gathered in Berlin to protest against Covid-19 lockdown measures. Although the event, organised by the Stuttgart-based Querdenker movement, defied a ban on public gatherings, it was ultimately a relatively peaceful affair. That was not the case with the next anti-lockdown demonstration in the capital, on 29 August.

Most of the 38,000 participants in the 29 August rally—which took place after an administrative court in Berlin overturned a police ban on the demonstration—did behave peacefully. But a splinter group of 450–500 protesters, many from the far right, attempted to storm the Reichstag. The assault was neither as violent nor as well planned as the one on the US Capitol that would take place on 6 January 2021—fuelled by America’s own ‘Q’, QAnon—but it was the first time since the Nazi era that the building had been violated. This does not bode well for Germany.

Fast forward to 1 August 2021. The Querdenker had applied for permission to stage a demonstration involving about 25,000 people, which the city declined on the grounds that the movement had repeatedly violated pandemic requirements. The organisers went to court and lost. However, a motorcade was allowed.

But the motorcade turned out to be a ruse. Instead, groups of Querdenker sympathisers started to march from different parts of the city with the alleged aim of congregating at the Brandenburg Gate and in front of the Reichstag. A rather surreal scene ensued. The 7,000 Querdenker, maskless and disregarding hygiene measures, enjoyed playing cat and mouse with the police, who had seemingly underestimated the likelihood and scale of the illegal rally, and the potential for violence.

A play on words, ‘Querdenker’ connotes contrariness on one hand and lateral thinking on the other. The movement was launched in April 2020 by a Stuttgart-based software engineer, Michael Ballweg, to promote one cause: the end of Covid-19 lockdowns.

According to Ballweg and his followers, public-health measures during the pandemic violate the German people’s constitutional rights, including that of free assembly. This is not untrue. But the government’s position—which reflects extensive deliberation in parliament and the courts—is that these temporary violations are warranted, given the severity of the Covid-19 threat.

The Querdenker are unconvinced. They accuse the government of using the pandemic as a pretext to establish a dictatorship. Their favorite slogan, chanted at many a lockdown protest, is ‘Peace, freedom, no dictatorship.’

Following the events of August 2020, the ‘peace’ part of that slogan is increasingly being called into question. So is the Querdenker movement’s focus on constitutional rights during Covid-19 lockdowns. As the movement has grown—there are now local chapters in 59 German cities—it has expanded the scope of its argument.

A recent Querdenker press release claims that the government has used the pandemic to create a ‘state of permanent surveillance’ and grant new powers to police and border guards, ‘in order to further restrict human rights across Europe’. Moreover, the movement asserts, the government has forced people to ‘lose their jobs … work overtime, forego wages, and ruin their health’, and destroyed young people’s future prospects by restricting education. Germany is now facing ‘the greatest redistribution from the bottom up, and a wave of expropriations of historic proportions’, and Querdenker will not ‘turn a blind eye’ to it.

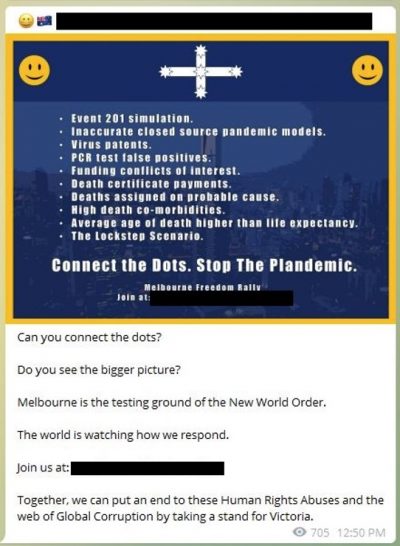

By linking its main concern to issues like state surveillance and economic inequality, the Querdenker movement has drastically expanded its potential support base. Anti-vaxxers, anarchists, libertarians, right-wingers and esoteric groups of all stripes have joined the cause. This is not unusual for a social movement of this kind, but it doesn’t do much for the Querdenkers’ credibility.

Ballweg denies Querdenker’s proximity to—let alone association with—extremists, claiming that such perceptions are the result of misleading and biased media reporting. But the most comprehensive study of the Querdenker movement, conducted by the sociologist Oliver Nachtwey and his team at Switzerland’s University of Basel, suggests otherwise.

The study covered pandemic-related protests in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. It found that movements were heterogeneous, comprising several, often disparate social groups. What united them was a sense of alienation from political institutions, established parties and the mainstream media.

This alienation, the study suggests, makes these movements vulnerable to conspiracy theories. Perhaps unsurprisingly, therefore, Querdenker demonstrations increasingly display anti-Semitic tendencies, though the movement is neither particularly xenophobic nor Islamophobic.

Querdenker is, Nachtwey and his team note, profoundly libertarian, and its followers tend to espouse beliefs in alternative medicine and holistic and spiritual thinking—a perspective closely linked to a distrust of modern medicine and science more broadly. Ultimately, they tend to share three key personality characteristics: fact resistance (typical of conspiracy theorists), a strong belief in their own version of the truth, and a self-righteousness bordering on arrogance.

A rightward shift is amplifying these tendencies. While Querdenker cannot be considered a right-wing movement, Nachtwey and his colleagues warn that the potential for radicalisation is rising. The right-wing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) has already voiced its support for the cause, and members of the Reichsbürger, a right-wing fringe group that denies the legal existence of the federal republic and seeks to reinstate some version of the pre-1918 German empire, have often participated in its rallies.

The question now is how Germany should respond. Some have called for Querdenker to be outlawed and its 59 chapters declared illegal. But the government has little appetite for such a drastic move, which could backfire, inciting more—and more violent—illegal demonstrations. One might also hope that, as the pandemic recedes, so will the Querdenker.

Yet, even if the movement fades, the alienation and distrust of authorities that have fed it are unlikely to go away. These same forces fuelled the Islamophobic Pegida movement, which held weekly rallies in Germany in 2015, but eventually dissipated, leaving behind a relatively small group of right-wingers. And they may well power the rise of another such faction after the next controversial political development.

It is these underlying drivers that the German government—and others, as this is hardly a uniquely German phenomenon—should be aiming to address. Profound transformation fuels anxiety and can make people feel, in the words of sociologist Arlie Hochschild, like ‘strangers in their own land’. Political ‘entrepreneurs’ like Ballweg—or, in the United States, former president Donald Trump—draw on these feelings to win support for themselves or their causes.

The lesson is as simple as it is challenging: governments must listen carefully, understand people’s anxieties, and identify actual and potential protest leaders before they engage, debate or try to convince the public of some crazed conspiracy theory. Over time, this approach can reduce the likelihood that destabilising extremist and populist movements will emerge, or at least lessen the risk of violence. In the meantime, these groups will remain a menace to society—and to democracy.