How the Collins submarine fleet went from near zero to hero

For most of the past decade, Australia’s six Collins class submarines have provided the nation with a fine underwater warfare capability. Designed to meet operational requirements beyond the capabilities of other conventional submarines, the government of the day has been able to rely on the availability of several highly capable submarines.

But it hasn’t always been that way. In fact, it was nearly 20 years after the delivery to the navy of the first of type, HMAS Collins, before the navy and government could reliably plan around the availability of submarines that were fit for purpose. For a long time, more than $10 billion of investment had provided the nation with very little payback in terms of a credible defence capability. Submarines spent years out of commission and availability across the fleet dwindled—sometimes to near zero.

The story of how the Collins class was finally brought up to a high standard of reliability is the subject of my new ASPI report, Nobody wins unless everybody wins: the Coles review into the sustainment of Australia’s Collins class submarines.

The problems with the Collins class began early. The building and delivery of the boats became highly politicised and the negative aspects that can reasonably be expected from any complex project—cost overruns, schedule slippages and technical problems that take time and effort to resolve—became consistent headline fodder. ‘Dud subs’ was a label that stuck.

That perception could have been put to bed once all the bugs had been ironed out and the submarines successfully put into use. After all, the original project problems with the F-111 were also well publicised and the subject of political point-scoring and public discontent with the cost. But once in service, the fuss died down, and the F-111 became something of a favourite at air shows and public displays—to the point of there being quite a bit of grumbling when they were retired.

Instead, in the years following the delivery of the last of the Collins class in 2003 and the resolution of most of the remaining technical issues, a new set of negative headlines started to appear. Partly through publicly available sources and partly through leaks from disaffected people within the submarine service and industrial support base, the parlous state of the fleet was revealed. A series of studies and reviews over the years—as many as 18 by some counts—identified issues and made recommendations but nothing seemed to make a lasting impression.

Within the world of submarine management, relationships between the operator (the navy), the contractor (ASC, a government-owned enterprise based in Adelaide owned by the Department of Finance) and the group within the Department of Defence responsible for project management (the Defence Materiel Organisation—DMO) had become highly dysfunctional and occasionally outright hostile.

By 2011 it was clearly that something drastic had to be done. The long lead time for the Collins class replacement meant that discussions for the successor class needed to start and early decisions about the direction of that project would be required. But it simply wasn’t possible to get traction on another very expensive submarine project when the existing fleet was essentially moribund—it would seem a case of throwing good money after bad.

The answer was for the government to sponsor yet another review. Many observers at the time (including me) were sceptical that another such exercise was unlikely to do much more than rearrange the proverbial deckchairs. In my ASPI role at the time I spoke to many of the key individuals involved. Opinions varied on many points of detail, but there was a unanimous view across the entire enterprise that it was someone else’s fault. Many meetings were called, with the usual outcome being that the warring parties would have another meeting at some future time. In between those meetings, metaphorical wagons were circled and arguments marshalled for future stoushes.

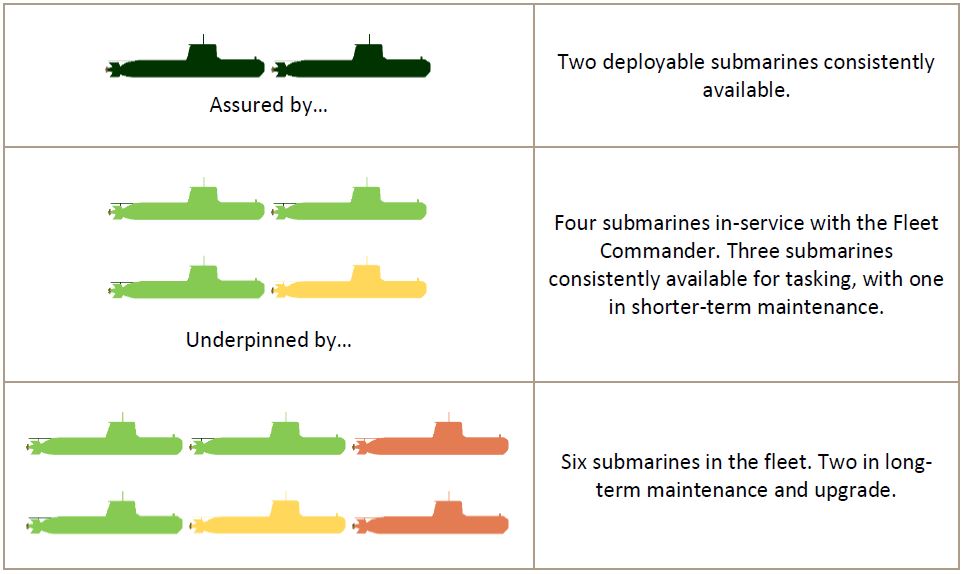

Many of the key players are quoted in my new report, and their views are often expressed quite candidly. That’s because at heart the woes of the submarine fleet were due to organisational issues and the breakdown of trust between the parties. The maintenance people at ASC felt that they were being micromanaged by the DMO to the point of not being able to do what they needed to do. The DMO felt that ASC were taking advantage of a contract that paid them whether or not the submarines were being maintained efficiently. The navy, ultimately the customer for submarine availability, didn’t have a clear understanding of what it could expect from a fleet of six submarines—and didn’t have a clear statement of its requirements in any case.

The review team that was put together was headed by John Coles, a British naval architect and engineer who had already established a track record for sorting submarine maintenance problems in the United Kingdom. The team was formidable—it wasn’t a consultancy group of generalists, but a small group of career professionals with hard-won specialist knowledge in submarine sustainment. That was to prove a crucial factor in the success of the review—the deep understanding of the business within the review team meant that nobody could pull the wool over their eyes.

It didn’t take Coles and his team long to work out that the Collins class submarines were fundamentally sound but the system (being generous with the term) put in place to support them wasn’t fit for purpose. And they also found that everyone wanted to fix the problem but that nobody agreed on what the causes of the problem were.

The whole story was a fascinating one to pull together. I’d tracked the facts and figures over the years, often reporting them here on the Strategist. And I’d been buttonholed at ASPI and Defence functions by enough people anxious to explain why those other guys were to blame to know that there were deep cultural divides at play.

The new ASPI publication explains how the ‘Coles review’ (as it became universally known) solved the problem. There was no magic formula: the answer was to work out in detail what needed to be done, who was best placed to do it, and then make sure that the delegated authorities and accountability mechanisms were in place to let them get on with it. The title of my report comes from Coles’ approach of making everyone a winner by enabling them to kick the goals they needed to kick while others did the same.

The improvement that followed the review and its implementation was swift and dramatic. The review did a comparative study of six other submarine-operating nations and found that Australia’s performance was by far the worst. In a couple of years, that had turned around to the point where Collins submarine availability exceeded the international benchmark, to the relief and delight of everyone involved.

There’s much more to the story than this brief overview, and there are lessons that go well beyond the narrow task of submarine sustainment. I hope the report gets widely read within the departmental and industrial organisations responsible for managing defence projects and delivered capabilities.

In particular, I hope those charged with the even more demanding task of preparing for Australia to get into the business of supporting, operating and one day building nuclear-powered submarines appreciate what they are getting into. As the experience with the Collins class showed, buying the hardware—however expensive and complicated that process can be—is only the beginning.

Source: John Coles,

Source: John Coles,