Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

The United Nations Climate Change Conference better known as COP26 that’s underway in Glasgow might conclude with a big international agreement. But whatever tactical successes are achieved at COP26, the results are likely to mark a strategic setback for humanity—at least when compared to the hopes of climate activists.

The world is missing target after target. This should not be surprising: while a growing number of countries have set net-zero targets, for example, very few have credible plans to meet them. And even if we did meet existing targets, that would not be enough to achieve the 2015 Paris climate agreement’s main goal: limiting global warming to 1.5℃ above pre-industrial levels.

In fact, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s latest report warns that the planet is likely to reach the 1.5℃ limit in the early 2030s. As long as multilateral engagement is defined by nationalism, power politics and emotion, rather than solidarity, law and science, our future will continue to grow bleaker.

At the height of the Cold War, the American television series The Outer Limits told the story of an idealistic group of scientists staging a fake alien invasion of earth, in the misguided hope that they could avert nuclear Armageddon by giving the world a common enemy against which to unite. When faced with the prospect of extinction, the logic went, the Soviet Union and the United States would turn their attention from competition to shared survival.

Today, nobody needs to contrive a common cause. Climate change poses as great a threat as any alien invasion. But, far from shocking national leaders out of their petty competition, it is being wielded as a weapon in a many-sided propaganda war. From Brazil and Australia to China and the US, countries are trying to game climate negotiations in order to shift the costs of adaptation onto others.

For example, the Brazilian government is trying to get the world to pay it to stop destroying the Amazon rainforest. Chinese President Xi Jinping will participate in COP26 only by written statement, and Russian President Vladimir Putin will not attend at all.

Meanwhile, the advanced economies—including those that proudly claim to be committed to climate action—have broken their promise to provide US$100 billion annually to support the climate transition in the global south. And even if they did deliver, it wouldn’t be enough.

Developed economies are finding increasingly coercive ways of shaping other countries’ behaviour. Commitments by most of the Western and multilateral development banks to stop financing coal (now joined by China) restrict options for grid expansion in developing countries where demand for power is growing rapidly.

Influential countries have also urged the International Monetary Fund to attach green conditions to debt relief for poor countries, as well as to its new allocation of special drawing rights (the IMF’s reserve asset). And the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism—a non-trade barrier intended to force exporters to Europe to shift to green production—disproportionately hurts small emitters in Africa and Eastern Europe with a lot to lose.

This is not to disparage coal bans, green financing and carbon pricing. On the contrary, these tools have a crucial role to play in changing how the global economy works. But that doesn’t mean we can disregard the (very serious) consequences for developing economies. Instead, we need to create a new grand bargain focused on supporting adaptation in the developing world.

More broadly, we must ensure that any multilateral agreement for tackling climate change is governed by international law, rather than dependent on the will of individual countries. And decision-making should be driven by scientific truths, not political slogans.

The Paris climate agreement’s predecessor, the Kyoto Protocol, adopted in 1997, was broadly in line with this approach: it was a multilateral treaty, with legally binding international targets determined by the world’s best scientists. But the protocol also had many flaws and it didn’t end up going far.

The Paris accord took a very different tack. It was hailed as a triumph because hopes for any agreement were so low. But it entailed a major compromise: it was based on non-binding commitments known as nationally determined contributions. Countries could simply pursue the energy policies on which they had already decided, while pretending they were working together to tackle climate change. Not surprisingly, current NDCs are wholly inadequate to achieve the agreement’s stated goals.

To be sure, climate-change COPs have often made important—if often procedural, boring and technical—contributions to the climate fight. But showboating and power politics have stood in the way of real progress. And the media and civil-society circus that surrounds the conferences—intended to enforce accountability and transparency—has often impeded negotiators’ ability to get things done.

More fundamentally, COPs have failed to produce a model of global governance that can tame power politics, let alone forge a sense of shared destiny among countries. And there is little reason to believe this time will be different.

Of course, the problem extends beyond UN climate change conferences. While economic globalisation has lifted millions out of poverty, it has fuelled an increasing concentration of wealth. In this context, efforts to advance shared interests can become less appealing, because they produce asymmetrical rewards.

Add to that the psychology of envy unleashed by social media and it becomes all the more difficult to shift people’s focus from their relative position in the global pecking order to the common good. These trends have undermined faith in the power of government and fuelled pessimism about the possibility that any solution will emerge.

The result is what social scientists call a collective action problem. Leaders and citizens alike conclude that the most rational short-term strategy is to pay lip service to the cause and hope others will solve the crisis. Meanwhile, the planet burns.

Will soaring prices for coal, oil and gas speed their replacement by renewables or foster a surge of investment in fossil fuels?

The new political economy of climate change is facing a head-on collision with the old-fashioned market economics driven by supply and demand in global energy markets. Australia finds itself uncomfortably at the point of impact.

The radical green fringe which in the 1970s postulated human-induced climate change has gone mainstream with 64 nations now having some form of carbon-pricing scheme raising revenue. Australia and the United States are among a tiny handful of developed nations that do not.

The Australian government’s adoption of a net-zero emissions target for 2050 doesn’t reflect a damascene conversion by the prime minister who four years ago brandished a lump of coal in federal parliament to mock the opposition’s embrace of renewables. Rather, it reflects an appreciation of the formidable forces building internationally which are also reflected in the Australian electorate.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg expressed the motivation clearly in a speech to the Australian Industry Group in September. ‘Climate risk has become one of the key issues raised in my discussions with CEOs, investors and counterparts, here and overseas,’ he said.

‘Considerations around climate risks are now being hard-wired into how global financial institutions allocate capital—at both a firm and country level—and how they engage with clients and companies.

‘We cannot run the risk that markets falsely assume we are not transitioning in line with the rest of the world.’

Frydenberg said Australia had long depended on imported capital to fund the economy. Banks secured around 20% of their wholesale funding from global markets; foreign investment in Australia stood at $4 trillion while foreign investors held about half the government’s bonds.

‘Reduced access to these capital markets would increase borrowing costs, impacting everything from interest rates on home loans and small business loans, to the financial viability of large‑scale infrastructure projects. Australia has a lot at stake.’

Frydenberg noted that major investing institutions like BlackRock, Fidelity and Vanguard were committing to zero emissions. A US database reports that almost 1,500 investing institutions around the world, with a combined worth of US$40 trillion, have committed to divesting from fossil-fuel businesses.

So the political economy of climate change is both acting to reduce demand for fossil fuels by imposing taxes on carbon that stimulate a shift to renewables and also squeezing supply by choking the flow of funds going to fossil-fuel-intensive industries.

And yet the world still depends on fossil fuels for around 80% of its energy. Right now, fossil fuel prices are soaring. Coal—the most reviled of all fossil fuels—hit a record of US$269.50 per tonne on 6 October, with Australia’s coal out of Newcastle setting the global benchmark price. Australia is the world’s largest coal exporter.

Oil prices have soared from last year’s extraordinary low of US$12.80 to US$83.60 a barrel, the highest in seven years. Spot prices for liquefied natural gas have also been at record levels, with the commodity now fetching more than US$50 per million ‘British thermal units’, a phenomenal increase from as little as US$2 a year ago.

Demand for energy has surged as the global economy emerges from the pandemic-induced recession. Investment in renewables has grown rapidly over recent years but has weakened in most fossil fuels, partly because of the pressure of investment and financial institutions that are increasingly shunning the sector. The result is shortages and soaring prices.

A market economist would say that taxes on carbon emissions to reduce demand for fossil fuels are the best way to achieve a shift in energy consumption patterns. Subsidising renewables is less efficient, and waiting for technological solutions is equivalent to prayer.

But trying to quash supply by starving new projects of capital or by regulatory fiat will only result in the prices that provide an incentive for new projects which will be funded by someone, if not the major institutions, when the profits are high enough.

The political economist will respond that all weapons must be deployed if the imperative of shutting down the fossil-fuel industry is to be achieved.

This clash between the political economy of climate change and the market economics of the energy industry was on display last week when the secretary-general of the United Nations, Antonio Guterres, commented that the top hydrocarbon-producing state in the US, Texas, needed to look beyond oil and gas to renewables. ‘If Texas wants to remain prosperous in 2050 or 2070, Texas will have to diversify its economy and Texas will have to be less dependent on oil and gas,’ he said.

The Texas governor, Greg Abbott, responded that the UN should ‘pound sand’—a US idiom equivalent to ‘jump in a lake’—tweeting, ‘The world is reeling from spiraling fuel costs caused by premature over-reliance on renewable energy. High fuel costs punish middle class families & stoke the supply chain crisis. Texas oil & gas is needed right now.’

A savage article in the New York Times about Australia’s lack of commitment to curbing emissions noted that the New South Wales government had approved three new coalmines in the past month and had 20 new coalmining projects under review. India’s Adani Group is forging ahead with the construction of the world’s largest coalmine west of Rockhampton in Queensland.

‘At a time when climate change and those who fight it demand that coal be treated like tobacco, as a danger everywhere it is burned, Australia is increasingly seen as the guy at the end of the bar selling cheap cigarettes and promising to bring more tomorrow,’ the paper said.

While spending on coal exploration is still far below the $1 billion a year peak reached during the resources boom, the $450 million invested in 2020–21 in Queensland and New South Wales is more than double the level of the previous year.

Woodside Petroleum is expected to give the go-ahead in December to a new $16 billion LNG plant to service its Scarborough field off Western Australia. It would be the first investment approval for an Australian LNG plant in a decade following the resources-boom investments that made Australia the world’s biggest LNG supplier.

Fossil fuels account for around 20% of Australia’s export earnings. The Department of Industry’s , compiled in June before the latest surge in prices, predicted that earnings from coal, LNG and oil would soar almost 40% over 2021–22 to surpass $100 billion.

Although much of the profit from Australia’s fossil-fuel production goes to overseas shareholders, enough remains in Australia through wages, superannuation earnings, taxes and royalties for the industry to be an important contributor to the Australian economy that no government can ignore.

So despite the plan to reduce Australia’s net emissions to zero by 2050, which relies on advances in technology rather than any government suppression of either supply of or demand for fossil fuels, it is possible that the world’s investing institutions will make the sort of adverse judgements about Australia that Frydenberg fears.

It could be argued that Australia would be in a better position to continue supplying fossil fuels if it were doing something meaningful to curb demand, although it’s likely that any such proposition would fall on deaf ears among the political economists shaping climate policy in both the public and private sectors around the world.

These are demanding times. Geopolitical tensions are rising, primarily—but not exclusively—between China and the United States. Yet, at the same time, there is a deep need for inclusive global cooperation to fight the pandemic and meet the threat of climate change. How the leading powers manage these competing demands will set the course of global development in the years and decades ahead.

Over the past few weeks, the US and China have attempted to establish some guardrails to prevent rising tensions from spiralling out of control. Following a recent meeting in Switzerland with his Chinese counterpart, Yang Jiechi, US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan spoke about the need for ‘responsible competition’ between the two countries—a choice of words we haven’t heard before.

But as welcome as this rhetoric is, the reality is that the US and China are still locked in a deepening rivalry. The decision by the US and UK to supply Australia with nuclear submarines—the delivery of which will not come for many years—was intentionally framed to seem like a major strategic move to counter Chinese maritime expansion. Similarly, at a two-day meeting in Pittsburgh last month, EU and US officials outlined an agenda for new talks on trade and technology, placing special emphasis on the need for defensive measures against China. In Washington, speculation about a potential Chinese invasion of Taiwan is running rampant and driving numerous decisions.

An increasingly authoritarian and assertive China isn’t the only geopolitical concern. Russia, too, poses a revisionist threat, with President Vladimir Putin issuing pronouncements that openly challenge Ukrainian sovereignty and cast doubt on the utility of diplomacy in handling the war in Ukraine’s Donbas region or issues stemming from Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Just as many in the US see a drift towards war with China over Taiwan, many in Europe worry about a similar escalation with Russia over Ukraine.

But the need for cooperation to meet even larger challenges should be obvious. When world leaders gather in Rome later this month for the G20 summit, they will have to confront the fact that we have made it only halfway (at best) in our fight against the Covid-19 pandemic.

At a recent summit hosted by US President Joe Biden, representatives from more than 100 governments, international institutions, businesses and civil society organisations committed to vaccinating ‘70% of the population in every country and income category’ by next September. That target is still a long way off. At the moment, approximately 38% of the global population has been fully vaccinated, and there is a glaring and dangerous inequity between high- and low-income countries. Indeed, high-income countries have administered 32 times as many doses per inhabitant as low-income countries.

The truism that no one is safe until everyone is safe is as relevant as ever. There’s no guarantee that the Delta variant will be the last mutation to trigger new epidemic waves. It is humanity versus the virus. We urgently need to mobilise additional resources to distribute not only vaccines but also tests and treatments. In this context, China’s potential contributions cannot be ignored. It produces more vaccines than any other country, and it will play a key role in any new global structures that are created to prevent or fight future outbreaks (any one of which could be far more dangerous than Covid-19).

Likewise, when global leaders meet for the UN climate change summit (COP26) in Glasgow next month, they will have to make up for lost time. A recent report from the International Energy Agency paints an alarming picture of how much work there is to be done to decarbonise the economy. This year, we will see the second-highest increase in carbon-dioxide emissions in history, indicating no progress towards a 2050 net-zero emissions target. Worse, governments’ current pledges cover less than 20% of the reductions needed by 2030 to keep global warming within 1.5°C of the average pre-industrial temperature.

Everyone must do more, but few single actors are as important as China. If it doesn’t reduce its enormous dependence on coal, global targets will remain out of reach. China’s recent announcement that it will end its overseas financing of coal projects is potentially very significant: that alone could reduce emissions by as much as the EU reaching net zero by 2050. But even then, China and everyone else will have more to do.

As with the pandemic, climate change puts all of humanity on the same side against a threat that could all too easily spiral out of control. To be sure, today’s geopolitical tensions are real, and issues like Taiwan and Ukraine must not be neglected. Democracies have every reason to stand together against revisionist aggression. But the pandemic and climate change are problems that can be addressed effectively only if everyone is committed to working together. Achieving that outcome will require true global statesmanship, and progress towards it must be the standard against which diplomacy is judged.

Nation-building can drive economic prosperity, social cohesion and resilience, but we need to engage with the complexity of our modern world to develop pragmatic solutions that address several issues. The temptation to rate one priority higher than another is strong, but we need to avoid binary choices. When it comes to climate policy, that can be challenging.

We’re seeing this now in Australia with the debate about committing to a net-zero emissions target by 2050. Despite support for the target from states and territories and the Business Council of Australia’s recent proposal for more ambitious 2030 targets, we’re still debating targets rather than focusing on how we should make the transition away from fossil fuels.

Whatever the target, we need to pursue a range of whole-of-community, cross-sector transition strategies. Carbon farming is one of the many approaches already being used.

Carbon farming refers to agricultural or land management practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions by capturing carbon in vegetation or soils or minimising emissions. The carbon credits generated from carbon farming can be used to offset emissions generated in other activities. Credits can be transferred through a commercial transaction to organisations seeking to offset their carbon generation. Eligible projects include activities related to vegetation management, agriculture, energy consumption, waste, transport, coal and gas production, and industrial processes.

Extensive effort to develop accounting and management methodologies to support carbon farming is paying off. Around 700 carbon farming projects are underway across Australia that together have reduced emissions by about 60 million tonnes or around 10% of Australia’s total emissions. And an increasing number of projects are being established in northern Australia.

The Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative) Act 2011 provides farmers, pastoralists, forest growers and landholders with opportunities to generate credits that can be traded in domestic and overseas carbon markets.

Given the scale and location of the Defence Department’s landholdings, there’s significant potential for the defence organisation to engage more actively with carbon farming. Defence emits around 1.6 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per year, which is more than half of all federal government emissions. Around 50% of Defence’s emissions come from the defence estate. In a recent Strategist article, Michael Thomas and Anthony Bergin suggested that Defence ‘undertake an audit of its estate for carbon offsetting and sequestration opportunities’.

The NT government has declared its intent to transition to a low-carbon economy and has set a target of net-zero emissions by 2050. Carbon offsets are expected to support achievement of the target as part of a broader emissions reduction strategy. While the voluntary carbon credit market under the Northern Territory Aboriginal Carbon Strategy is smaller than the federal government’s Emissions Reduction Fund, it is expected to grow and contribute to emissions reductions, particularly through fire management on savannahs.

The Aboriginal Carbon Foundation estimates that there are 55 savannah projects underway in the north which have generated $20 million in carbon credits, with around $112 million in carbon credits contracted under the Emissions Reduction Fund. These projects aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through a strategic fire management program focused on early-season burning and ‘cool’ planned burns, which generate relatively low greenhouse gas emissions. The intent is to prevent or reduce the scale of unplanned and more destructive late-season fires, which generate higher greenhouse gas emissions.

Indigenous communities in the north are embracing carbon farming—not as a binary option but to generate community income, increase local employment and develop local skills and, equally important, to enhance people’s connections with the land and build a socially engaged community.

But the results are mixed for farmers and pastoralists and the benefits for their communities are not as clear. While carbon farming allows individual landholders to establish a more reliable income stream by storing carbon in vegetation and trees, it is having a negative impact on the sustainability of local communities.

Queensland’s Paroo Shire has been in the spotlight in recent months because of the negative impacts that carbon farming in the shire is having on local communities. By the end of 2020, Paroo’s 47 carbon farms had earned more than $40 million and the region expects to generate around $230 million over the coming decade.

The concern is that corporations are buying up large landholdings and not contributing to the local community by generating local jobs, keeping families in the area or supporting local businesses. There’s also debate about adverse environmental impacts that some Paroo farmers say were caused by an increasing wild dog population.

In contrast, the Budjiti Aboriginal Corporation in southwest Queensland is embracing carbon farming as a means of regenerating the environment, creating income for traditional owners and returning to traditional land management practices.

As the NT government develops its broader policy to guide the application and administration of carbon offsets, it should take communities’ recent experiences of carbon farming into account to ensure that the economic, social and resilience benefits are optimised.

Carbon farming is producing economic benefits and is offsetting our carbon footprint. The challenge is to ensure that other benefits are achieved by weighting economic, social and resilience effects equally. Carbon farming could represent a form of nation-building that drives sustainable economic, social and environmental outcomes at the regional level. But we need to avoid binary choices if we are serious about transitioning to a net-zero emissions world.

Pick any sector of the European economy, and you will find a lot of companies cutting greenhouse-gas emissions. But, while sectors like construction, electricity production and agriculture now emit much less than they did in 1990, transport emissions have increased by 33%. Unless we put the brakes on transport pollution soon, the European Union will have a very hard time reaching its climate goals.

There is an important economic dimension to the challenge ahead. Europe’s highly competitive automotive and transport industry plays a key role in driving its economic growth and employment. If Europe falls behind in developing and adopting sustainable technologies within the next decade, it will pay a high price.

The EU cannot afford to follow Asia and North America’s lead on sustainable technology. Nor can it keep taking baby steps. Instead, policymakers must act boldly to accelerate the transition to sustainable transportation by supporting innovation and dismantling barriers to green investment in the sector.

Innovation does not mean only inventing new technologies. More fundamentally, it means devising new ways of doing things. And when it comes to transport, plenty of technologies that are already available can drive rapid progress on sustainability.

For example, electric vehicles and battery technology are becoming more advanced, accessible and affordable by the day. Battery costs have declined by more than 80% since 2010, and sales of electric cars increased globally by 73% in 2018 alone. Meanwhile, big data, artificial intelligence and digitisation are enabling further innovations, from ride-sharing platforms to self-driving cars. Given that cars, trucks and other road vehicles account for more than 70% of all transport emissions, the potential for progress is huge.

Yet cutting-edge technologies are not the only way to achieve more sustainable transport systems. During the Covid-19 pandemic, cities across Europe created temporary bicycle lanes, leading to a surge in cycling. Some heavily trafficked roads, such as Paris’s Rue de Rivoli, were also transformed into pedestrian zones.

These initiatives not only promoted zero-emissions transport and helped local businesses survive the pandemic, they also proved that significant progress can be made with measures already at hand.

Still, overcoming many transport challenges will demand much more research and development. Slashing emissions from ships and planes is one clear example. More broadly, large and timely investments are needed to cut technology costs, increase efficiencies, support first-movers and create new markets.

But investing in new green technologies is risky. We often don’t know what the big breakthroughs will look like or which technologies will prevail. It’s hard to commit large amounts of capital to charging networks or hydrogen gas if it is not clear which fuels people’s vehicles will be using.

Faced with a high degree of uncertainty, firms and public institutions often adopt a wait-and-see attitude and delay investment. With banks wary of taking the plunge, many companies in Europe cannot find the investment they need to support innovation. In the meantime, investors might continue to finance old, ‘dirty’ technologies, in order to meet short-term needs.

Changing investors’ calculations requires creating financial tools that spread risk among many parties, along with policies and regulations that make it easier to develop new infrastructure and technology.

Public banks such as the European Investment Bank have a vital role to play here. By taking advantage of loan guarantees, venture capital and public-private partnerships, we can take more chances on innovative start-ups, research projects, demonstration plants, and the commercial deployment of new technologies.

Already, the EIB has backed an early demonstration plant by Northvolt in Sweden to develop some of the world’s most modern batteries and has committed financing to the Dutch company Allego to deploy ultra-fast vehicle charging stations in many European cities. We are also assisting in the rollout of 5G mobile networks across Europe. This will enable superior communication between connected vehicles, making driving much safer and improving the chances that technologies like self-driving cars will succeed. The EIB is also a key supporter of electric trains and trams across Europe, the goal being to reduce the number of cars and trucks on the road.

We constantly review new financing plans for European start-ups developing electric bicycles, vision sensors for autonomous vehicles and charging systems. And our advisory services help cities across Europe achieve objectives like finding new financing for electric buses or designing towns that encourage cycling and walking.

Yet the climate crisis demands global solutions. That’s why the EIB is also supporting green transport far beyond Europe’s borders. For example, we backed the construction of metro systems in the Indian cities of Bangalore, Lucknow and Pune. And, together with the World Bank and the governments of Luxembourg and Germany, we established the City Climate Finance Gap Fund, which focuses on launching green investments in the Global South, including in the transport sector.

But the fact remains that there is not enough public money in the world to finance the transition to a low-carbon future. Ultimately, the private sector must take the lead. Major industrial players, entrepreneurs and grassroots organisations must adopt a more agile, daring and even revolutionary approach. The EIB will be there every step of the way, offering guidance and sharing the risk.

Record-breaking temperatures and extreme weather across Europe and North America in recent months should leave little doubt that we have entered a make-or-break decade on climate. To create a sustainable future, we must embrace creativity and openness, ensuring that Europe’s brightest minds and boldest initiatives receive the support they deserve.

Within weeks, Prime Minister Scott Morrison will almost certainly announce an Australian commitment to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. He will do so with an eye to the domestic politics of the upcoming election, but also under pressure from key allies such as the United States.

Having committed to sharing sensitive nuclear submarine technology with Australia, Washington now will expect Canberra to contribute more on the climate front. In his recent meeting with the US president, it’s highly likely that Morrison reassured Joe Biden that Australia will sign up to net-zero emissions before the Glasgow climate conference, with the precise timing hinging on sensitive ongoing discussions within the Coalition. If so, it shouldn’t be surprising that climate change references in the AUSMIN and Quad joint statements mostly reflected Australia’s existing climate commitments or that the Americans refrained from publicly ramping up climate pressure during Morrison’s visit.

Recent reports also suggest that opposition to the climate commitment is diminishing inside the Coalition. The PM’s negotiating position is reinforced by the fact that every state and territory has already committed to net zero by 2050. New South Wales also recently announced that its 2030 emissions reduction target will increase from 35% to 50%.

Three related aspects of Morrison’s upcoming announcement will be key in terms of its credibility internationally and its domestic political impact, including on the election. The first concerns the nature and scale of the concessions Morrison makes to secure the support of his Coalition colleagues. Emissions are typically sorted into seven sectors across the economy, and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has said that reductions are needed in all of them, including mining and agriculture. These last two are areas that some National Party ministers are keen to protect. The credibility of the government’s net-zero commitment will be undermined if these sectors are excluded. It will also be undermined if securing the Coalition’s support comes at the cost of significant pork-barrel funding to key Nationals constituencies.

The second aspect will be how ambitious the intermediate emissions reduction target is. A weak 2030 target will suggest the government is kicking the can down the road, and will call into question Australia’s ability to meet the 2050 deadline. Australia’s current commitment is to reduce greenhouse gases by 26–28% below 2005 levels by 2030. The PM is likely to increase that somewhat in his announcement, perhaps to 30–35%. US officials have suggested the figure should be closer to 50%, in line with the more ambitious targets set by many of our closest allies.

The third relates to how the government proposes to achieve the emissions reductions. It’s reasonable and responsible for the Coalition to choose measures that minimise the cost to the nation of achieving net zero. But the choices necessarily require many assumptions, including about the pace of technology development. Generally, the more the commitment relies on new or untested technologies, such as carbon capture and storage, the less credible it will seem.

The US government invested billions of dollars in carbon-capture demonstration projects that were never completed and it recently suspended indefinitely its only commercial power plant using the technology. The same applies to relying heavily on carbon offsets to achieve reductions. Carbon-offset schemes suffer from many flaws, including the absence of an official international standard for carbon accounting for the offsets. They are seen as a useful component of the response, but not as a substitute for deeper national reductions.

Australia’s action on climate change will certainly feature prominently in the election campaign, including these three aspects of the PM’s forthcoming net-zero announcement. Morrison has recently suggested that he may not attend the Glasgow conference because, as he put it, ‘I have to focus on things here and with COVID. Australia will be opening up around that time.’ If he doesn’t go, it will reinforce views in the electorate that the government isn’t taking climate change seriously. If Covid-19 is the reason he skips Glasgow, when so many other heads of state are attending, criticism of the government for the slow pace of the vaccine rollout could resurface. The political risks have further increased for Morrison with former PM Malcolm Turnbull’s and Fortescue Metals Group chief Andrew Forrest’s recent announcements that they’ll be attending the climate meeting.

Less than a year ago, it seemed almost inconceivable that this government would commit to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. A number of factors have contributed to a change, including the election of Biden, the growing climate commitments of Australia’s key trading partners, the continuing rapid decreases in the costs of renewable energy and battery storage technologies, the commitment of financial regulators and the world’s largest asset managers to address climate risk and, of course, the rapidly increasing frequency and severity of global climate disruptions, including the Black Summer bushfires here in Australia, which directly affected almost 60% of Australians.

The Australian public is increasingly concerned about climate change and calling for strong responses from the government. It remains to be seen if the electorate will view the PM’s plan for achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 as a sufficiently strong response to the climate threat.

India’s commitments under the 2015 Paris climate agreement, which aims to limit global warming to well below 2°C relative to pre-industrial levels, include three quantifiable objectives. By 2030, the country aims to reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP by 33–35%, ensure that renewable energy sources account for about 40% of its installed power capacity and, through afforestation, create an additional carbon sink of 2.5–3 billion tons of carbon dioxide equivalent.

International observers like Climate Action Tracker and Climate Transparency regard India as one of the few G20 countries to be ‘2°C compatible’ and on track to fulfil its so-called nationally determined contributions (NDCs) under the Paris accord. But even if India achieves its NDC targets and adopts measures to help keep global warming to 1.5°C, on current trends its CO2 emissions in 2030 could be about 90% higher than in 2015.

India must therefore decarbonise more, and fast. But India also needs to invest in manufacturing and infrastructure to improve its competitiveness, create enough jobs to lift a third of its 1.3 billion people out of poverty and increase its chances of meeting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Achieving these objectives without drastically increasing carbon dioxide emissions will require India to pursue a radically different green growth strategy.

This will not be easy. True, with renewable energy sources currently accounting for 140 gigawatts, or 37%, of India’s 380 gigawatts of installed power capacity, the country looks set to achieve its 40% target by 2030. But only 15.5% of the electricity consumed in India is clean, while the remainder is sourced through fossil fuels. That is primarily because large additions of renewable-energy capacity do not translate into lower CO2 emissions in linear fashion. The effect instead depends on the capacity utilisation of renewable sources, the grid’s capability to absorb variable power and the flexibility of power systems to ramp up during peak loads.

While India is the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, its per capita electricity consumption is among the world’s lowest, at about one-third of the global average. But it is imperative that the country’s electricity consumption increases as the economy continues to develop.

The energy sector alone accounts for 78% of India’s greenhouse gas emissions, while industry is responsible for 7%, and agriculture and land use 10%. Within the energy sector, industry is the biggest consumer of electricity, using 42% of India’s output. As the country’s low per capita resource consumption rises towards the global average, and with demand for carbon-intensive commodities such as steel, cement and chemicals expected to grow, electricity consumption is likely to increase at least threefold between 2014 and 2030.

Structurally transforming the Indian economy will entail a shift in the share of GDP from agriculture to industry and services, accompanied by a reduction in energy poverty and improved access to reliable electricity. This would be the required development trajectory for achieving the sustainable development goals, but it would result in India increasing its CO2 emissions.

So, how, and to what extent, can India decarbonise? The solution lies in deploying clean technology on a large scale, reducing the cost of finance, and pricing and paying for emissions mitigation.

To promote both decarbonisation and economic development through a green investment and growth strategy, policymakers should consider adopting a sequenced approach. They could start by investing in large-scale renewable-energy projects, before electrifying transportation and then expanding and integrating distributed green energy for cleaner electricity access.

The next step would be to create additional rural non-farm livelihoods in agricultural processing (milling, grinding, crushing and packaging), storage and warehousing. After that, policymakers should aim to increase energy efficiency in heating, cooling, lighting and electric motors. India also will need to adopt clean technologies such as carbon capture and storage, hydrogen as a fuel and reducing agent for steel, and green cement manufacturing. And it must expand its forestry-based carbon sinks on a massive scale.

Speeding up decarbonisation in line with India’s NDC calls for massive investments totalling some US$2.5 trillion by 2030. Most emissions-mitigation technologies require large upfront capital investments relative to subsequent operating costs, which is why India’s relatively high cost of finance is an important factor. And increased risk perceptions of the country—including climate-related financial risks—make it difficult to reduce borrowing costs for climate investments. Large-scale green investments in India therefore may not provide adequate risk-adjusted returns.

That means India requires interventions from government and intergovernmental institutions to enable finance to flow toward decarbonisation investments. These measures could include creating pooled or specific risk-mitigation mechanisms to ‘de-risk’ finance; shifting investments from banks to financial markets; reducing reliance on credit ratings for lending and investment; measuring, registering and pricing carbon mitigated incrementally beyond NDC targets; and compensation for additional perceived risks borne by banks and institutional investors.

The risks are indeed high. A long coastline, widely varying seasonal monsoons and significant dependence on agriculture make India highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. This is evident from increasingly frequent cyclones, droughts and erratic temperatures across the country.

India therefore requires climate-adaptation investments that would preserve ecosystems and reduce coastal erosion while protecting livelihoods. Because the private sector usually perceives core adaptation investments as economically unviable, the public sector must lead by making suitable investments and developing public–private partnership business models to attract private investors.

Indian policymakers should thus regard meeting national climate targets under the Paris agreement as only a first step. The far bigger challenge is to foster sustainable green growth that provides a better future for India’s people while also helping to protect the planet.

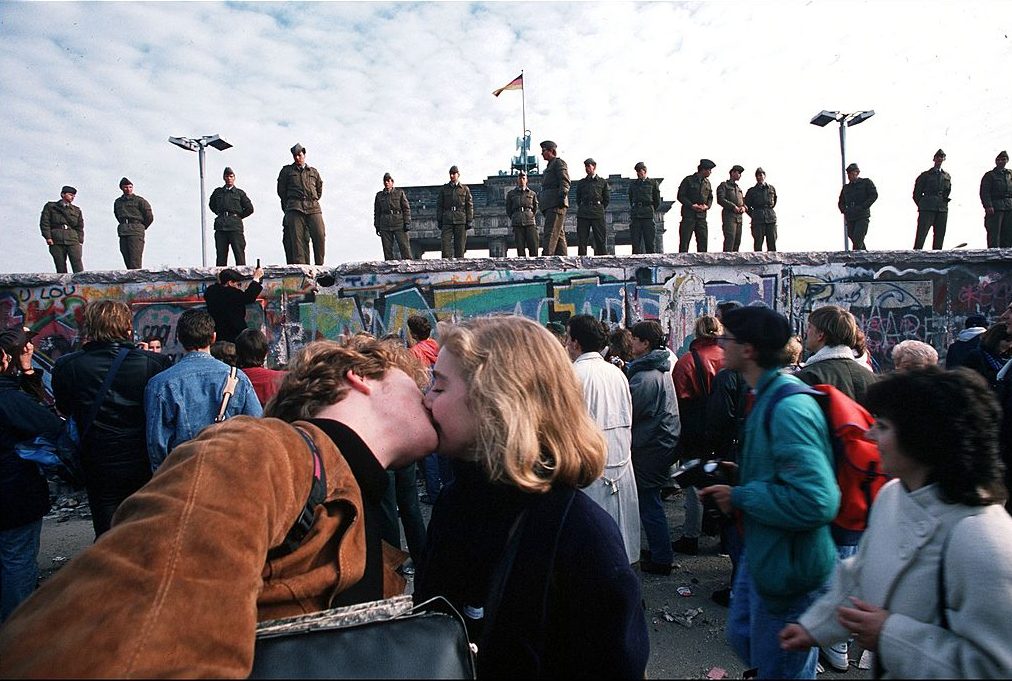

My political awakening coincided with the systemic changes that unfolded following the collapse of communism in Hungary in 1989. I was both fascinated and overjoyed by my country’s rapid democratisation. As a teenager, I persuaded my family to drive me to the Austrian border to see history in the making: the dismantling of the Iron Curtain, which allowed East German refugees to head for the West. Reading many new publications and attending rallies for newly established democratic political parties, I was swept up by the atmosphere of unbounded hope for our future.

Today, such sentiments seem like childish naivete, or at least like the product of an idyllic state of mind. Both democracy and the future of human civilisation are now in grave danger, beset by multifaceted and overlapping crises.

Three decades after the fall of communism, Europe is again being forced to confront anti-democratic political forces. Their actions often resemble those of old-style communists, only now they run on a platform of authoritarian, nativist populism. They still grumble, like the communists of old, about ‘foreign agents’ and ‘enemies of the state’—by which they mean anyone who opposes their values or policy preferences—and they still disparage the West, often using the same terms of abuse we heard during communism. Their political practices have eroded democratic norms and institutions, destroying the public sphere and brainwashing citizens through lies and manipulation.

Nativist populism tends to be geared toward only one purpose: to monopolise state power and all its assets. In my country, Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s regime has almost captured the entire state through the deft manipulation of democratic institutions and the corruption of the economy. Next year’s parliamentary election (in which I am challenging Orban) will show whether Hungary’s state capture can still be reversed.

I believe that it can be. But to hold populists wholly responsible for the erosion of our democracy is to mistake cause and effect. The roots of our democratic shortcomings run deeper than the ruling party’s fervent nationalism, social conservatism and eagerness to curtail constitutional rights. Like the rise of illiberal political parties in older Western democracies, democratic backsliding in Central and Eastern Europe stems from structural issues such as rampant social injustice and inequality. These problems owe much to the mismanagement and abuse of the post-1989 privatisation process and transition to a market economy.

Older, well-established democracies are experiencing similarly distorted social outcomes. With the development of a socially minded welfare state in the immediate post-war decades (a period that French demographer Jean Fourastié famously called ‘les trente glorieuses’), economic growth in Western democracies allowed for a massive expansion of the middle class. But this was followed by a wave of neoliberal deregulation and market fundamentalist economic and social policies, the results of which have become glaringly visible today.

More than anything else, it was the radical decoupling of economic growth from social welfare that let the illiberal populist genie out of the bottle and broke the democratic consensus in many countries.

Even worse, our generation is cursed with more than ‘just’ massive political and social upheaval. We are also facing a climate crisis that calls into question the very preconditions upon which modern societies are organised. Progressives like me see this, too, as a direct consequence of how our economic system works. Infinite, unregulated economic growth—capitalism’s core dynamic—simply is not compatible with life on a planet with finite resources. As matters stand, our capitalist system drives more extraction and generates more emissions every year.

Faced with such challenges, we cannot allow ourselves to succumb to fatalism or apathy. Progressives, after all, must believe in the promise of human progress. Our institutions and economic policies can be adapted to account for changing circumstances. Injustices that alienate people from democracy can be rectified. Channels for democratic dialogue can be restored.

As the mayor of Budapest, a major European city, I can attest to the fact that local governance matters. Whether it is through democratic engagement, emissions reductions or social investment (areas where we have already made significant strides despite fierce resistance from the Orban regime), local governments are well positioned to improve citizens’ lives. And by doing so, we can also create synergies and new models that will contribute to larger-scale progressive change. So, beyond what we do on our own, the city of Budapest is eager to contribute to all international efforts aimed at preserving democracy and a liveable planet.

To that end, we will hold the Budapest Forum for Building Sustainable Democracies this month to bring together a wide range of stakeholders, including mayors, European Union officials, activists and high-profile academics. Participants will discuss strategies for tackling the most pressing policy challenges of our time, and then provide forward-looking, practicable policy recommendations.

As part of the forum, Budapest will also host a Pact of Free Cities summit to build a broader global network of progressive mayors and city leaders who are committed to the defence of democracy and pluralism. More than 20 city leaders—from Los Angeles to Paris and Barcelona to Taipei—are joining an alliance created by the capital-city mayors of the Visegrad Four (the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) in December 2019.

Martin Luther King, Jr. said that those who want peace must learn to organise as effectively as those who want war. The same is true of democracy. With the Budapest Forum and the Pact of Free Cities, Budapest intends to help organise forces from all segments of society to ensure a democratic and liveable future in Central and Eastern Europe and beyond. We must win the intellectual fight against nativist populism and the civilisational fight against climate change—and we must do both at the same time.

In the lead-up to the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party last month, hundreds of Chinese coal mines were ordered to shut down to ensure the celebrations weren’t marred by any fatal accidents.

There had been a spate of coal- and gas-related tragedies, but the enforced closures led to shortages, contributing to rising prices for coal both for power stations and steel mills.

According to the South China Morning Post, 130 mines with a combined capacity of 186 million tonnes a year were closed in Shanxi, the biggest coal-producing province, while similar measures were implemented in other provinces.

The shutdown pushed prices to new peaks. Domestic Chinese thermal coal prices reached the equivalent of US$150 a tonne, and the metallurgical coal needed by steel mills rose above US$300 a tonne. Those prices are more than double the levels earlier this year.

The China Coal Transport and Distribution Association called on state-owned coal miners to restart their shuttered operations, and the National Development and Reform Commission authorised the release of 10 million tonnes of coal from the government’s strategic stockpile.

The coal market highlights the irreconcilable pressures confronting the Chinese government.

It wants to lower carbon emissions in line with Xi Jinping’s promise to the United Nations last year of a peak in China’s emissions by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2060. China’s embrace of ambitious climate targets was designed to get ahead of America on the eve of last year’s US presidential election.

The Chinese authorities also want to reduce the dependence of economic growth on real estate and infrastructure, which are pushing debts to unsustainable levels. There’s also concern that the unbridled growth of the steel industry as it responds to demand from these sectors is contributing to inflation by dragging commodity prices ever higher.

In pursuit of these goals, the government has ordered steel production this year not to exceed the 1.05 billion tonnes produced in 2020. It has also handed out some economic punishment to Australia by banning purchases of Australian coal, on which it had spent $14 billion in 2018–19.

On the other hand, the authorities are concerned that China’s growth would have slowed last year without the benefit of the government’s stimulus spending on real estate and infrastructure and they fear more of the same will be required over the year ahead. They worry that slow growth will raise unemployment and undermine popular support for the government.

For the moment, the concern about slowing growth appears to be winning. Steel prices have fallen in the wake of a politburo statement last Friday that ordered local governments to rein in their ‘campaign-style’ carbon-reduction plans, saying work to meet emissions targets should be ‘orderly and unified’.

Although the politburo’s comments are Delphic, the Financial Times cited the interpretation of Morgan Stanley that ‘With the politburo’s comment, we expect steel production controls will be more gradual paced going forward.’

Beijing believed that local authorities were taking the order to cut emissions and steel production too literally, particularly after steel production had surged 11% in the first six months of the year. Harsh cutbacks to steel production were pushing up the price of steel as construction and industrial firms tried to secure supplies. If the steel mills couldn’t respond to the demands of the infrastructure and property-development industries, China would struggle to reach its growth targets.

University of Peking finance professor Michael Pettis says it’s important to distinguish between what Beijing refers to as ‘high-quality growth’ driven by industrial output and household consumption and ‘residual growth’, which is the infrastructure and real estate spending unleashed whenever the central government’s growth targets look like being missed.

In a newsletter, he says there has been a fierce debate over whether Beijing should be more concerned by rising debts or slowing growth. He argues that the ‘residual growth’ costs more to the economy than it delivers and brings no gain to living standards. But he says the central government is likely to force local governments to increase their support for property and infrastructure developments over coming months, pushing GDP growth towards 8% this year and raising debt levels to new heights.

Reducing carbon emissions will become a lower priority, and China’s steel mills and power stations will continue to struggle with shortages of their key commodities, coal and iron ore.

It may be reading too much into Friday’s politburo statement, but it’s striking that at the meeting of G20 climate and energy ministers in Italy last month, China joined India and Russia in opposing a resolution to mandate the shutdown of coal-fired power and to ban international finance of coal mining.

The stance taken by the trio has cast a shadow over hopes for a radical strengthening of global climate action at the Glasgow climate conference in three months. China’s burst of good intentions last year on curbing emissions may be confronting economic reality.

The decision to ban Australian coal, which has been enforced since last October, has been problematic for both China’s steel mills and its power stations. Although the steel mills have been able to replace Australian coal with Mongolian coal, the latter is lower quality and industry analysts say its use without blending with the high-quality coal that Australia is known for will result in damage to the coke ovens at the major mills and ultimately the loss of steel-making capacity.

China’s biggest source of thermal coal imports, in Australia’s absence, has been Indonesia, but its production has been hampered by heavy rainfall, and supplies from Russia and South Africa have also been interrupted.

A drought in southern China cut the availability of hydro power. Although China has been rolling out wind and solar power, their intermittent supply means the country has been relying more heavily on coal to meet the surge in demand for power over the summer.

For both metallurgical and thermal coal, the ban on Australian imports has resulted in a two-tier market, with Chinese buyers having to pay more for coal than the rest of the world. Australia is having to settle for lower prices, but has largely succeeded in replacing China as a customer.

The capacity of the Australian Defence Force and other key agencies must be increased urgently to enable them to deal simultaneously with climate-driven disasters at home and in the region while countering worsening security threats, food shortages and mass people movements.

This grim warning is delivered by climate change specialist Robert Glasser in a report, The rapidly emerging crisis on our doorstep, released by ASPI today. An internationally respected climate specialist, Glasser was previously the United Nations Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Disaster Risk Reduction.

He now heads ASPI’s new Climate and Security Policy Centre established to help increase Australians’ understanding of the cascading effects of rapidly increasing temperature rises including flooding, hunger caused by a sharp reduction in crop sizes and declining fish stocks, conflict and mass people movements.

Glasser says Australia urgently needs to think about political, economic and security tipping points generated by climate change. ‘Any one of the increasing risks would be serious cause for concern for Australian policymakers, but the combination of them, emerging nearly simultaneously, suggests that we’re on the cusp of an unprecedented and rapidly advancing regional crisis.’

One of the areas likely to be worst hit by accelerating climate change will be maritime Southeast Asia (MSEA), directly to Australia’s north, and Glasser says the emerging regional impacts could overstretch the nation’s operational capacities to act, such as by creating demands on the ADF to simultaneously support disaster relief at home while responding to fast-growing regional security challenges.

Glasser says the MSEA region is exceptionally affected by the hazards that climate change is amplifying. ‘Those hazards will not only exacerbate the traditional regional security threats that currently dominate military and foreign policy planning in Canberra, such as the rise of China, terrorism and separatist movements, but also lead to new threats and the prospect of multiple, simultaneous crises, including food insecurity, population displacement and humanitarian disasters that will greatly test our national capacities, commitments and resilience. So these hazards have serious implications for regional economic development, political stability and security.’

He says there’s a growing realisation in Australia and in its Quadrilateral Security Dialogue partners, the United States, Japan and India, that climate change will have an increasingly serious impact on regional security.

‘The posture, training and capabilities of the ADF will need to change so that it can be part of Australia’s response to more frequent, higher impact regional natural disasters. Its capability set will also need to evolve to equip it to operate at greater scale and in places affected by large natural disasters,’ he says.

MSEA faces a dangerous constellation of simultaneous climate hazards, says Glasser. The sea level there is rising four times faster than the global average, driven by climate change and other factors. It has the world’s highest average sea-level rise per kilometre of coastline and the largest coastal population affected by it.

Climate tipping points are thresholds that, once exceeded, trigger cascading impacts, such as the sudden release of massive amounts of methane gas from thawing arctic permafrost, which would greatly accelerate warming.

Australia must ensure it has the capacity to lead regional responses to the many natural disasters emerging from a warming climate, Glasser says.

‘We can’t wait for the severity of the situation on our northern doorstep to become obvious before we act, as the pace of climate change impacts is rapidly accelerating and many of our responses to those threats require long lead times to identify, plan and implement, particularly as they will require multilateral as well as national responses.’

The Bureau of Meteorology has begun supporting national security agencies to identify the potential impacts of adverse weather and climate on food security, refugee migration and conflict.

Glasser says this must become part of a much wider, whole-of-government process involving Defence, Home Affairs, Foreign Affairs and Trade, CSIRO, Health, Agriculture, and other departments and agencies.

US President Joe Biden’s whole-of-government approach to climate change demonstrates what can be done when the issue is put at the centre of national security planning, Glasser says.

Australia should identify priority investments to build the capability within Defence, Foreign Affairs, the intelligence agencies, Home Affairs and other departments to recognise emerging climate impacts and establish an ongoing process to re-evaluate the evolving strategic equation in the light of regional developments and as our capacities and understanding improve.

With that greater knowledge, we’ll also be in a better position to identify opportunities, such as aid interventions, to reduce the risk at critical points but also to make investments that build our capacity for regional stabilisation and humanitarian response missions.

‘It’s becoming increasingly clear that the Australian aid program will need to scale up its efforts to strengthen regional resilience to climate change, particularly in MSEA. Recent compelling analysis suggests that helping less developed countries to adapt to climate change can reduce the likelihood of conflict and forced migration,’ says Glasser.

MSEA is also a hotspot for cyclones, which strike the Philippines more often than any other country. The warming climate is making these cyclones more powerful and, together with sea-level rise, is rapidly amplifying storm surges and flooding.

‘In only a matter of decades, what has historically been a 1-in-100-year extreme flood will become an annual event across much of the region,’ Glasser says.

Regional temperatures may rise by 1.5°C within a decade, driving extreme weather which will have major impacts on food security, the availability of water, and disease. The region will also experience more frequent swings from extreme heat and drought to severe floods.

Crop yields will be reduced by rising temperatures, changes in rainfall, the expansion of the reach of crop pests and shifts in predators that keep crop pests in check. The number and duration of heatwaves are already increasing, with hundreds of millions of people already exposed to extreme heat, including in the agriculture sector. Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines are among the most at risk of the heat-related loss of labour capacity.

Scientists have determined that by 2040, at 2°C of warming, Southeast Asia’s per capita crop production may decline by a third. At the same time, it will become increasingly difficult for nations to import food to feed their populations.

Fish stocks are declining as they move away from warming waters and as the coral reefs that provide their breeding areas collapse.

Glasser says regional nations have made enormous economic progress in recent decades, with the Indonesian economy projected to become the world’s fourth largest by 2050. ‘But there remain significant vulnerabilities that will become sources of instability as the climate continues to warm, particularly in Indonesia and the Philippines, where about a quarter of the countries’ populations live on less than US$3.20 per day.’

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria