The Defence White Paper gives an excellent description of the Asia Pacific but is calm about its dangers. It is heartening on the ADF’s capacity to defend the nation and its near neighbourhood and rightly reaffirms ANZUS and the US role: ‘It is unambiguously in Australia’s national interest for the US to be active in our region as economic, political and military influence shifts towards it’. It’s also correct not to name China as an adversary. Saying what we stand for in the Asia Pacific, and how we plan to protect it, is more pertinent than saying who we fear.

The Defence White Paper gives an excellent description of the Asia Pacific but is calm about its dangers. It is heartening on the ADF’s capacity to defend the nation and its near neighbourhood and rightly reaffirms ANZUS and the US role: ‘It is unambiguously in Australia’s national interest for the US to be active in our region as economic, political and military influence shifts towards it’. It’s also correct not to name China as an adversary. Saying what we stand for in the Asia Pacific, and how we plan to protect it, is more pertinent than saying who we fear.

But we can’t hide the fact that China is probing on multiple fronts for more space and clout, sustaining quarrels with numerous neighbours who are Australia’s friends. The only reason Australia is not among those nibbled, along with Japan, Vietnam, Philippines, India and others is that’s so far away. This partially justifies the White Paper’s silence, but is short-sighted.

There is no integration of the Alliance with the overall regional picture to manage what is a marked new challenge to the status quo. The White Paper seems reluctant to state the values that bind Australia and its friends together. Stating our values is not provocative. If that’s a message to China, it’s in the eye of the beholder.

The White Paper speaks eloquently of the need to protect prosperity and stability. But where do these two desiderata come from? Long-term stability comes from democracy and freedom of the individual. Prosperity comes through free markets and free trade. Happily, China has embraced the values of economic liberalism to a considerable extent, but they are not Chinese values. Rather they are long-time Western values, and if the US and its allies don’t defend them they might not endure.

Confusion over Japan is related to this point. You can’t talk of the US and China as the two ‘global powers’ and relegate Japan to ‘regional power’. It is not just that in a decade or two the labels might have to be changed, but right now the White Paper’s assessment of power undervalues democracy and free markets in the making of stability.

True, the entire White Paper assumes the centrality of a US-led equilibrium to Australia’s security and prosperity. But it’s content with a vague hope to ‘develop the security structures on our region to help ensure cooperation…’. Lame references to ‘rules of conduct’ and a ‘rules-based global order’ (which doesn’t exist) send no message to Beijing that Australia opposes the weakening of the existing equilibrium in the Asia Pacific. Beijing respects strength more than Western-derived rules of conduct.

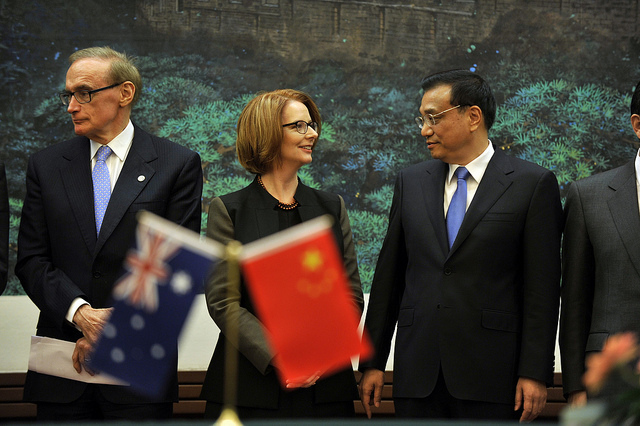

Ross Terrill of Harvard’s Centre for Chinese Studies is a visiting international senior fellow at ASPI. Image courtesy of Flickr user Julia Gillard.