Rising China, troubled America, crouching Australia

Not too far back in Australian history, large amounts of anger and angst—buried not too deep in the national psyche—would have arisen if Chinese warships had conducted exercises in Australia’s maritime approaches.

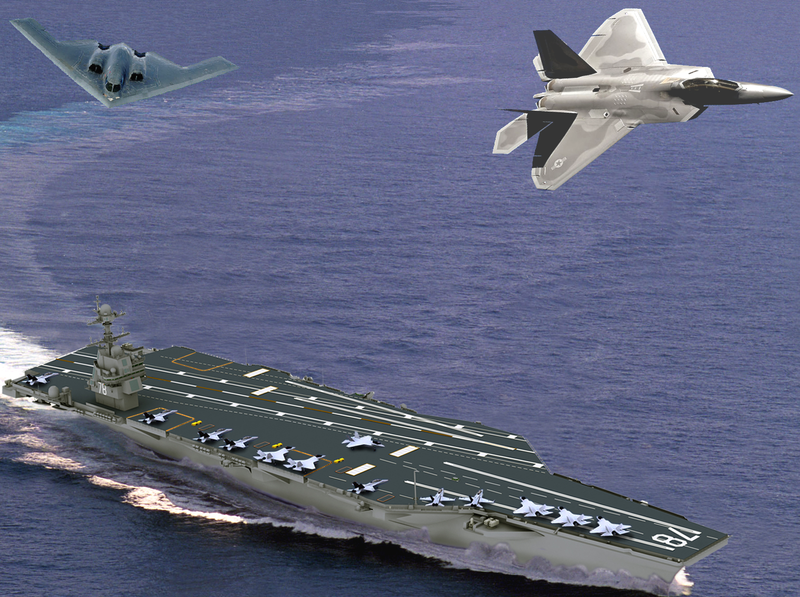

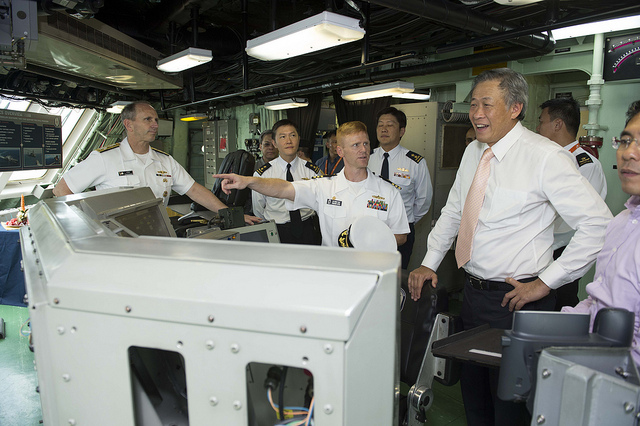

Now, for the first time, China’s Navy has done just that. Two Chinese destroyers and a landing ship carried out the exercise—as legal as it was unannounced—between Christmas Island and Java, before heading out into the Indian Ocean. Little wonder the Australian Air Force ‘scrambled’ and did some surveillance.

No public anger is on show but some low-level angst is about. Rory Medcalf and C.Raja Mohan argue that China’s going Indo-Pacific and the exercise is ‘a wake-up call to anyone still doubting China’s long-term intention to be able to project force in the Indian Ocean.’ Read more