A rising power looks down under: Chinese perspectives on Australia

Today ASPI has released a Strategy paper examining Chinese perspectives on Australia. Dr Jingdong Yuan has drawn from official Chinese documents, leaders’ statements, media coverage, academic analyses, and interviews with specialists to provide a detailed insight into Chinese views of Sino-Australian relations. Using this insight, Dr Yuan provides recommendations to the government on the continued development of the growing relationship between Australia and China. Here’s the executive summary:

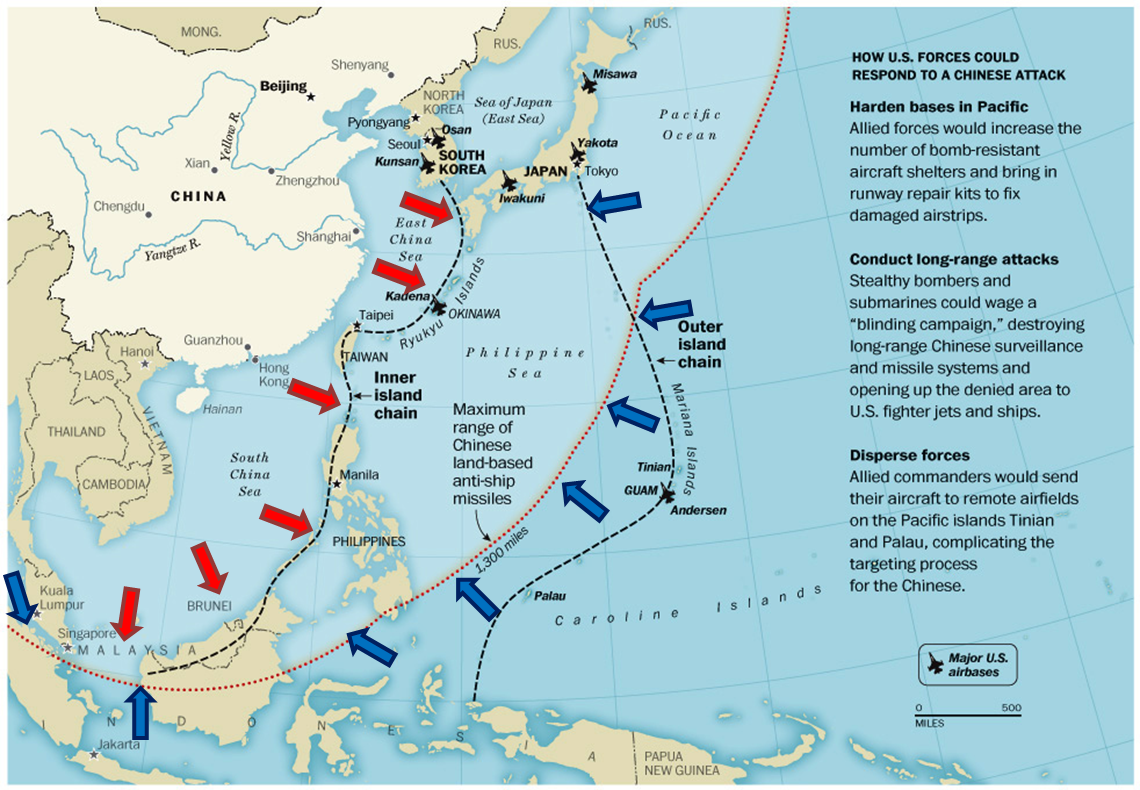

Sino-Australian diplomatic, economic and security ties have experienced significant growth over the past four decades. The general trends have been positive, especially in the economic area, where the two countries have developed strong and mutually beneficial interdependence. China has become Australia’s largest trading partner, and its growing demands for resources will continue to affect Australian economic wellbeing. Australia, in turn, has become a major destination for Chinese tourists and a favoured choice for higher education. Canberra has played an important role in encouraging and drawing China into regional multilateral institutions such as APEC, and the two countries have cooperated on major international and regional issues. However, bilateral relations periodically encounter difficulties and occasionally suffer major setbacks, largely due to differences in ideologies and sociopolitical systems, issues such as Tibet, Taiwan and human rights, and emerging challenges ranging from cybersecurity to the geostrategic shift in the region marked by China’s rise and the US’s rebalancing to Asia. Read more