China’s disinformation on Xinjiang is political warfare, not diplomacy

The Chinese Communist Party is launching increasingly bold and sophisticated information operations in an attempt to shape international perceptions of its treatment of religious and ethnic minorities in Xinjiang.

A new report from the ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre’s research program on disinformation highlights the lengths to which the CCP is going to deflect concerns about Beijing’s treatment of Uyghurs and others.

Chinese diplomats and state media have been prolific in their commentary on Xinjiang and exploit the reach that they gain from access to US social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.

According to data from 2018–2020, state media were consistently in the top 10 Facebook accounts accumulating the most ‘likes’ on posts mentioning Xinjiang.

CCP propaganda is also increasingly laundered through Western influencers and denialist fringe media outlets like The Grayzone. Between December 2019 and February 2021, The Grayzone was cited at least 313 times in Chinese state media.

Individuals and organisations (including ASPI) have documented human rights abuses in the region, and the EU, the UK, Canada and the US recently imposed coordinated, targeted sanctions on CCP officials. The CCP retaliated using a combination of sharp statecraft: sanctions of its own directed at elected officials and think tanks; wolf warrior ‘diplomacy’ intermingled with overt disinformation; information operations; and economic coercion.

Beijing’s reaction has been eye-opening for some European officials, coming so soon after the negotiation of the EU–China investment deal. But this is not diplomacy; it is political warfare. This is how the CCP projects political power and defends against external threats.

ASPI researchers have tracked Beijing’s shifting threshold for risk in its information operations, which are a central component of the CCP’s political warfare. The party-state has faced a number of crises and challenges—the Hong Kong protests, the intensification of its rivalry with the US, Covid-19—that it seeks to turn into opportunities.

Beijing is calculating that its recovery from the economic shock of the pandemic and the internal rifts among democratic states are opportunities it can capitalise on.

The CCP’s information operations are growing in scale and reach. We have previously analysed its large-scale covert information operations on US social media platforms that focused on the Hong Kong protests, the Taiwanese presidential election and Covid-19.

Like the CCP’s nascent digital diplomacy, these initial efforts were limited in their capacity to shape opinion on an open internet unconstrained by CCP censorship. But they were persistent and managed to retain a large on-platform presence. They’ve improved and become increasingly agile, as demonstrated when they pivoted to capitalise on domestic protests and politics in the US.

Throughout 2020, these covert information operations attempted to create the perception of moral equivalence between China and the US. This work continues and has become a feature of the party-state’s diplomatic messaging. Foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying has tweeted historical photographs of cotton-picking in the US to amplify racial division, and compared these images to the CCP’s efficient mechanised production of Xinjiang cotton.

Prominent wolf-warrior diplomats like Zhao Lijian and Hua Chunying are able to grab the headlines to steer the focus of the media cycle in a direction more preferable to Beijing, but the party-state has realised that it needs to speak with a more colloquial voice if it’s to actively shape opinion in the West. In our analysis of the coordinated information campaign by Chinese diplomats and state media to discredit the BBC, we identified several novel tactics adopted by the CCP.

The party-state’s propaganda apparatus is becoming increasingly adept at repurposing pre-existing grievance narratives that resonate more clearly with target audiences (as it did in its targeting of the BBC).

Another emerging tactic is the repurposing of organic content sourced from Chinese and US social media platforms. Recycling organic content (as Zhao did with his infamous tweet of an image of an Australia soldier with a bloodied knife holding an Afghan child) helps party-state officials to engage social media audiences with content that is effectively framed for the medium while staying on just the right side of platform content-moderation policies on the propagation of disinformation.

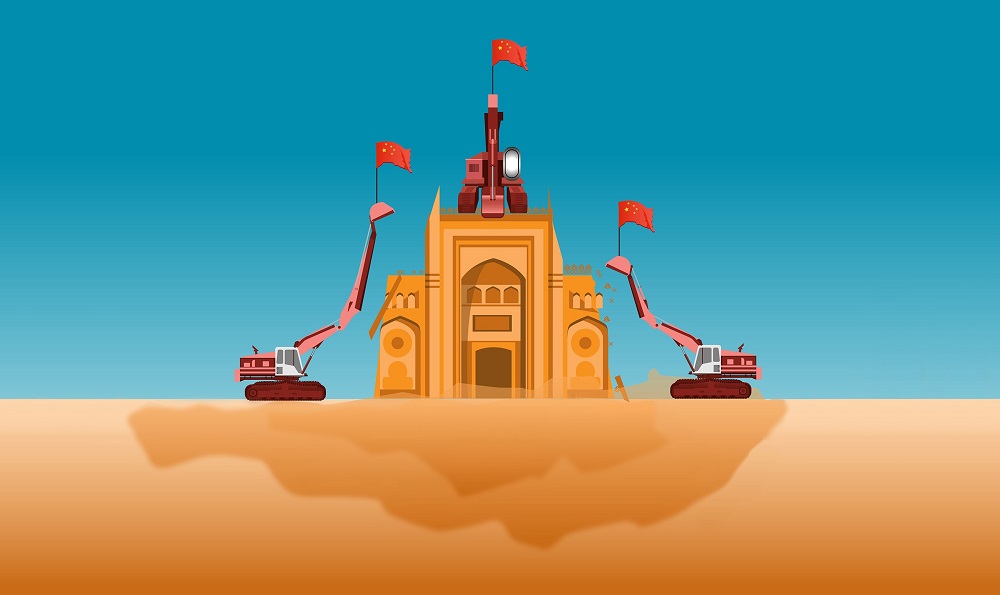

Our latest report highlights the ways in which the CCP is outsourcing the dissemination of disinformation. It does so by tendering to companies such as the United Front Work Department–linked Changyu Culture, based in Xinjiang. Videos created by the company attempt to whitewash international political discourse on the treatment of the region’s Uyghur population and are amplified by fake social media accounts on US platforms that the mainland Chinese population doesn’t have direct access to.

Our data demonstrates that the CCP is increasingly leveraging fringe sites like The Grayzone as vehicles for its own propaganda. These sites have pre-existing audiences that the CCP can exploit to inject disinformation into the Western media environment.

The boycott of Swedish company H&M by Chinese consumers and retailers demonstrates the CCP’s capacity to mobilise audiences at scale across Chinese and US social media platforms in ways that carry economic costs for targeted states and entities.

The CCP doesn’t need to win over the West. It just needs to convince the rest of the world that democracy is in decline and that their future is best served in Beijing’s strategic orbit.

Democratic states must understand that when the party-state’s officials, state media and covert propaganda operate in coordination with economic coercion and sanctions to suppress and pre-emptively censor international criticism, they are not dealing with diplomacy but are facing a salvo in the political warfare being waged by the CCP.