Graphic online depictions of sexual assault, homophobia and racist imagery (sometimes involving Australian lawmakers) and life-threatening intimidation (including calling for targets to kill themselves) are a growing part of the Chinese Communist Party’s toolkit of digital transnational repression. Such imagery, and associated threats, characterise ongoing coordinated information operations the CCP is running online against women of Asian descent living in democracies around the world, including in Australia, the UK and the US.

This strand of cyber-enabled foreign interference—targeting both overseas public debates and key women within those debates—continues without consequential intervention from policymakers or social media platforms.

In Australia, parts of this campaign are seeking to interfere in public debates by using the #auspol and #qanda hashtags. Concerningly, a more sophisticated subset of posts are seeking to engage in political interference by promoting a fringe Australian political party. This highlights the importance of prioritising cyber-enabled foreign interference, both as a major part of the next national cyber strategy and in Australia’s foreign policy.

If Elon Musk drills down to examine Twitter’s work on state-backed information operations and platform manipulation, he will discover he’s taking over a platform considered industry leading in areas such as transparency, data sharing and policy responses designed to deter such activity. Policymakers and regulators around the world will watch closely to see if Musk’s known support for freedom of speech results in an open slather on the vulnerable, including reductions in transparency and data sharing. Recent news that Twitter has slashed its workforce, including teams responsible for dealing with misinformation and hateful conduct, will be setting off alarm bells for officials.

Notwithstanding Twitter’s reputation for prioritising its work in this space, Chinese state-backed information operations are proliferating on Twitter because they are now on all major platforms. They are becoming more sophisticated and increasingly target countries, elections, policy topics, organisations and individuals.

Commentators and industry figures have argued that some of these operations are low impact, including because they attract little genuine online engagement. But such arguments rely solely on online metrics that don’t factor in the distressing impact it has on the targeted individuals (or companies) or those who worry that they too could become targets. They also don’t consider the wide range of activity now occurring across global platforms, including the more insidious forms of state-backed activity that have more recently emerged.

Since ASPI first revealed in June 2022 that the CCP had turned its disinformation and coercive capabilities towards women of Asian descent reporting critically on China—including journalists, researchers and human rights activists—new evidence suggests the party has stepped up its psychological-warfare techniques. The following tweets were all posted in the past fortnight:

‘People like you who betray the motherland, smear and slander at will, are really inferior to dogs.’

‘Traitors will not end well.’

‘I think you’d better see a doctor, you’re scared you’re going to self-harm.’

‘If you enter this restaurant with a dog, the waiter will take care of the dog first.’

‘You should live your whole life with the guilt of killing your own mother.’

‘You are just relying on your Chinese identity and belittling your country to survive, you are just a tool. If you are not Chinese, your value is zero.’

‘I advise you not to run around. Stray dogs are easy to kill.’

These tweets form just a tiny percentage of the abusive and threatening messages targeting a small group of high-profile Asian women who’ve become a focus of this persistent and harmful activity. (Note: ASPI deliberately selected tweets that did not include the women’s names. Tweets of that kind are often more personalised and abusive.)

In addition to constant abuse, many of these accounts also tweet bespoke imagery (see Figure 1). These images are tweeted at the women, are circulated through hashtags and are also tweeted at other high-profile figures, including Australian politicians and journalists and think tankers who work on China.

Figure 1: Examples of abusive imagery tweeted at high-profile Asian women

ASPI assesses that, like previous Chinese-state-affiliated harassment and trolling campaigns, the Spamouflage network—which Twitter attributed to the Chinese government in 2019—is likely behind the targeting of these women. Twitter publicly confirmed that this was the case in response to ASPI’s June 2022 analysis.

Examination of these newly created accounts that reveals they repeatedly share the same images, mostly post content during Beijing business hours (see details on activity below) and use double-byte fonts commonly used in Asian languages. Accounts also previously shared the #USCyberHegemony hashtag, which is part of a broader CCP-linked propaganda campaign, and flooded other online platforms with pro-Chinese police content to drown out the latest report of the human rights organisation Safeguard Defenders on China’s transnational policing. Some accounts have diverted to focus on spreading propaganda claiming former CCP general secretary Hu Jintao was expelled last month from the 20th party congress because he was in poor health.

The coordinated activity targeting these women uses a combination of Twitter replies, direct tweets and quote tweets. It builds up dedicated hashtags about its targets and also seeks to tap into existing popular hashtags—those used internationally as well as domestically in countries where these women live (including #auspol in Australia). It includes crude imagery that appears to have been designed specifically for, and which links to, YouTube videos. In October, tweets that formed a part of this campaign led and dominated Twitter search results for related hashtags and versions of the target’s name.

The online activity we analysed is often highly customised and is clearly the result of extensive surveillance of each targeted individual to tailor messages and react quickly to developments in their lives. This includes information they’ve shared publicly and, for some, information they haven’t shared publicly. It’s all blended with disinformation, threats and abuse.

The tactics are multifaceted and are designed to intimidate and silence through constant harassment with misogynistic, racist and homophobic content. They also spread disinformation and abuse that seeks to undermine the credibility of the women being targeted by attacking their work, physical appearance, values and morals, ethnic background, sexuality, friendships, partners and deceased family members.

In addition to the examples given above (such as repeatedly being called a ‘dog’) smears such as ‘liar’, ‘biased’, ‘untrustworthy’, ‘promiscuous’, ‘prostitute’, ‘ugly’, ‘scum’ and ‘psychopath’, and insults like ‘beasts dressed in human skin’ are common. Accusations that they have betrayed and smeared their ‘motherland’ and any (real or perceived) links to a Western democracy, particularly any association with the US, are a key focus of the campaign (noting many of those targeted are actually citizens of the countries in which they live). Threats calling for women to kill themselves, or insinuating that they should do so, and telling them that their lives are in danger, are commonplace.

Three ongoing campaigns, in English and in Mandarin, stand out for their threatening approach; deep misogyny; and coordinated, persistent harassment.

For months, a network of accounts has harassed Jane Wang, a UK-based activist campaigning for the release of Zhang Zhan, a journalist jailed in China for her early reporting of the Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan. Under almost every tweet posted by Wang, accounts with anglicised names followed by eight numbers (a default format Twitter uses for newly created accounts) call her a ‘traitor’ and a ‘puppet of Western capitalism’. In one post referencing the Sitong Bridge protest, Wang received more than 588 replies exclusively from inauthentic accounts abusing her and seeking to undermine her credibility. Other accounts post highly sexualised cartoons depicting her being molested by another Chinese pro-democracy advocate, Qiu Jiajun, who has also been targeted separately by these accounts. Wang told ASPI that she has never met Qiu.

A second campaign targets ASPI senior fellow Vicky Xu, who has long been attacked by the CCP across multiple platforms—in China and globally—in an incredibly obsessive fashion. This campaign was reignited recently after Xu returned to social media after an extended break. A group of authors at the Chinese state-owned Global Times collectively named BuYiDao (补壹刀) published a hit piece about Xu in July 2022 and called her one of the ‘female vanguards against China’. The article currently has over 75,000 vitriolic comments, mostly calling for her execution.

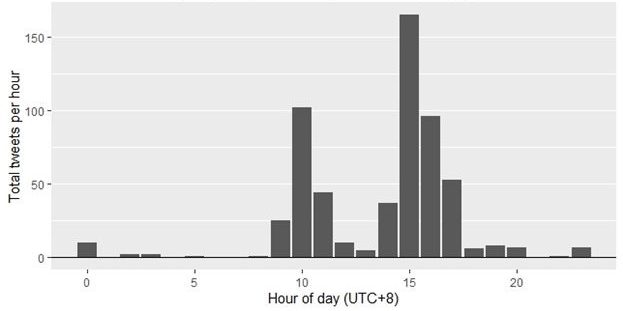

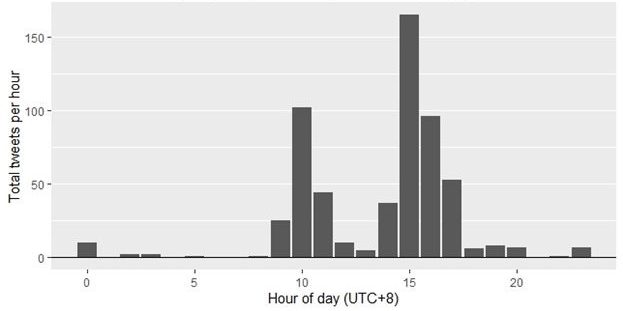

More recently, coordinated covert Twitter campaigns have escalated their abuse against Xu. Between 14 and 24 October, at least 199 accounts posted around 582 tweets mentioning her Chinese name, calling her a traitor and making physical threats. Of these tweets, 92% were posted between 9 am and 5 pm Beijing time, with a significant break in activity between 12 and 2 pm when businesses usually have their lunch break (Figure 2). Some of these accounts have already been suspended, but many remain active online and are harassing Xu hourly and in response to every post she tweets. One series of clearly concocted tweets asks, ‘Why didn’t you get hit by a car?’

Figure 2: Number of abusive tweets mentioning Vicky Xu by hour of posting, 14–24 October 2022

In an effort to tap into Australian public discourse and draw political and media attention, accounts posting about Xu often include hashtags such as #Australia, #Metoo and #Auspol and #qanda in their tweets. Short for ‘Australian politics’, #Auspol is one of Australia’s most popular hashtags discussing domestic politics, and #qanda is used to discuss the ABC’s weekly TV show Q&A. For Twitter users searching a combination of these hashtags—for example, ‘#Australia #metoo’ or ‘#Auspol #metoo’—tweets in this campaign are displayed prominently in Twitter’s search results, both in the ‘top’ and ‘latest’ categories. ASPI searched multiple times between 24 and 31 October.

These accounts also tag journalists, researchers and human rights activists. Some of these high-profile commentators tweet in response calling for action by Twitter.

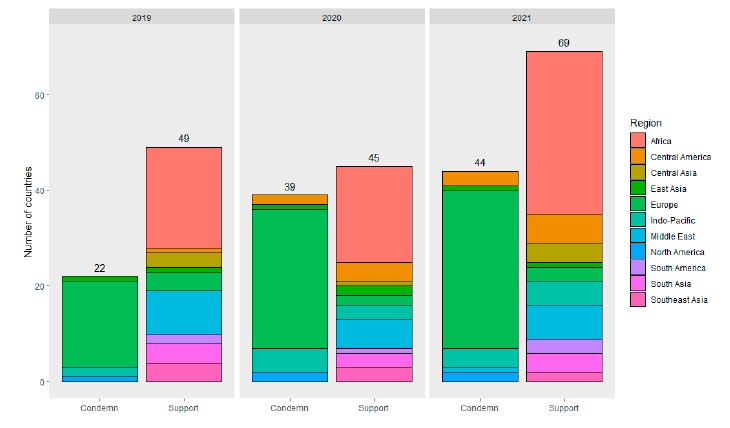

A linked but more sophisticated subnetwork of accounts that has recently started targeting Xu is also seeking to engage in more direct interference in Australian politics. Many of the accounts in this small network—which are new as of September and October 2022—are promoting the Australian Citizens Party, a fringe party affiliated with the LaRouche political movement. Commentary by the Australian Citizens Party is regularly promoted and cited by China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Chinese state media, and Chinese embassies and diplomats on social media.

Accounts in this network, some of which have also tweeted about or tagged ASPI (along with dozens of other organisations and individuals, including current and former politicians), are attracting more organic online engagement than other parts of the network. Their personas are slightly more authentic than other parts of the campaign and are sometimes based on real Australians. For example, one inauthentic account, ‘Erin Chew’, is based on a real woman named Erin Chew who works at the Asian Australian Alliance advocacy network (figure 3).

Figure 3: Example of tweet posted on inauthentic Twitter account ‘Erin Chew’

These accounts are seeking to drive online attention towards the Australian Citizens Party and its members, as well as public commentators in Australia and globally whose political beliefs sit on the alt-left of the political spectrum (through retweets and mass tagging of other accounts), including some individuals who promote conspiracy theories. They are seeking to engage in debates on topics including the state of Australian democracy, Australia–US relations, Australia–China relations and AUKUS. They are also making allegations of corruption in Australian politics.

While this small network is more sophisticated and far more proactive in its efforts to interfere in Australian political debates, it is still in its infancy and hasn’t yet had any serious impact.

The activity targeting Xu isn’t limited to US-based social media platforms. On Chinese social media, posts sharing photoshopped images of Xu in faked pornographic situations are prominently displayed at the top of search results under Xu’s Chinese name on Weibo, China’s equivalent of Twitter. That these posts remain visible on China’s domestic internet, where the government has criminalised highly sexualised content, means they are very likely to be state sanctioned and deliberately left uncensored to broaden their reach.

The activity doesn’t just target Wang and Xu. Many of the journalists targeted earlier this year when ASPI conducted its original analysis are still constantly abused. They include the New York Times’ Muyi Xiao, Washington DC–based video journalist Xinyan Yu and New Yorker writer Jiayang Fan.

Attacks on Fan are intense. On 27 October, for example, abusive and threatening tweets were sent to her every few minutes. One busy hashtag, #TraitorJiayangFan, is kept alive entirely by inauthentic accounts. Since January, more than 400 accounts have posted at least 4,300 tweets using that hashtag. Like the accounts targeting Vicky Xu, 90.9% of these tweets were posted between 9 am and 5 pm Beijing time.

Fan has previously written and spoken about being targeted by China’s propaganda apparatus and Chinese nationalist trolls, including while her mother was in hospital in 2021 during the Covid-19 pandemic. After Fan’s mother died in early 2022, the campaign cruelly pivoted to focus on her mother’s death, bombarding her with tweets accusing her of being responsible and warning, ‘Your mother’s experience will be repeated on you.’ Some tweets in the campaign link to crude YouTube videos, originating from Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, about the death of Fan’s mother, titled ‘You love America, but does America love you?’

Spamouflage’s persistent multi-year presence on US social media platforms has allowed the CCP to refine its ability to incapacitate groups of people and organisations seen as critics, such as journalists, researchers, dissidents, activists and victims of human rights abuse. Parts of this campaign are agile in responding to new developments—some accounts regularly divert from key targets to harass and threaten others in the China-watching community as they share their reporting and analysis on Twitter. Another common tactic is to create hundreds of replicant accounts of individuals and organisations to harass those targets and confuse online users (see figure 4).

Figure 4: Tweet from Jane Wang with examples of replicant accounts using her name

These campaigns can cause enormous harm to those targeted, and some of these women have already spoken about this publicly.

For democratic governments, this is about much more than a group of individuals being relentlessly harassed. The CCP is taking advantage of open societies that tolerate bona fide criticism of high-profile individuals. These women are targeted because of their gender and perceived ethnicity and because their work—even if only partially focused on topics that irritate the Chinese party-state—has a global reach. For the CCP, this potent mix is enough for it to invest serious resources into harming these women and seeking to deny them a public voice. It’s only a matter of time before the CCP expands its targeting to include politicians, industry leaders and other public figures who work on China. That would be consistent with the CCP’s increasingly aggressive interference in the political processes of democracies.

That these campaigns remain so prevalent, despite global media coverage and efforts from high-profile commentators to bring them to Twitter’s attention, highlights the massive scale of this problem. Much more work is required for social media platforms and policymakers to tackle the CCP’s increasingly global efforts to censor and interfere in public debates, to threaten and harass individuals and to spread disinformation outside China’s borders.

We propose eight recommendations for governments and social media platforms, focusing on enforcement, building deterrence, public signalling and transparency.

1. Social media platforms must better enforce their rules and terms of service prohibiting harassment, hateful conduct and threats of violence—all rules we saw repeatedly broken by many of the inauthentic accounts taking part in this campaign. Platforms should also invest more resources in beefing up their capabilities, human and technical, to identify and remove inauthentic material.

2. Social media platforms need to urgently shift their thinking and move from taking down these campaigns through a defensive ‘whack-a-mole’ approach to a more proactive stance. As an example, limiting searches of these women’s names, as appears to have occurred in some cases, is a band-aid solution that also punishes the victim. This feature may limit public access to some of the inauthentic activity under a particular search term, but it can also censor everything the public can see about that person—including authentic media about that person or their work and their own tweets. Restricting the reach of all content about and tweeted by the women who are being targeted just limits their voice further. Instead, platforms could remove access to the tweet analytics, such as impressions or engagements, of accounts identified in coordinated information campaigns. Depriving the operator of the metrics required to assess the impact of their operations will disrupt plans for future iterations.

3. Political leaders and parliamentary bodies, including in Australia, must take greater responsibility for ensuring that foreign states can’t so easily manipulate Western social media platforms to target elections, public discourse and individuals. Given the rapid rate at which CCP information operations are proliferating, it’s time for parliamentary bodies to commission dedicated inquiries into Chinese cyber-enabled foreign interference. They should work with all major social media platforms to share technical data with third-party researchers and cybersecurity experts. The US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence reports on Russia’s Internet Research Agency and the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence agency, could act as models.

4. Cyber-enabled foreign interference, in all its forms, needs to become a standard focus for governments in both cyber and national security strategies. Online interference often receives minimal attention in government strategies because of artificial and unnecessary distinctions between whether cyberspace is being used to commit malicious behaviour, is enabling malicious behaviour or is only a vector. This distracts from dealing with the problem. Cyber-enabled foreign interference is a growing policy challenge for democracies, yet most democracies only focus on it before an election. The result is that most other online interference that’s occurring falls through the cracks between policy and intelligence agencies. The reality is that we’re not even tasked or institutionally set to deal with a threat at which our adversaries excel. In Australia, the departments of Home Affairs and Foreign Affairs and Trade need to coordinate and lead on implementing policies to build greater deterrence, and they must engage closely with social media platforms as they undertake a more proactive stance.

5. Democracies should establish an Indo-Pacific hybrid threats centre. This could be modelled on the NATO–EU Hybrid Centre of Excellence in Finland, while reflecting the differences between the European and Indo-Pacific security environments. It would contribute to regional stability and enhance cooperation on the emerging security challenges countries in the region are struggling with while having few places to turn to for support and information sharing. The centre would build broader situational awareness on hybrid threats across the region and build confidence through measures supporting research and analysis, greater regional engagement, information sharing and capacity building.

6. Democratic governments should step up their global signalling. A group of democracies led by the US, Australia and the UK, whose citizens are targeted in this campaign, should coordinate a joint statement denouncing harassment and disinformation campaigns. Diplomats should work with the UN special rapporteur for freedom of opinion and expression and the new UN high commissioner for human rights to investigate the perpetrators of such online attacks.

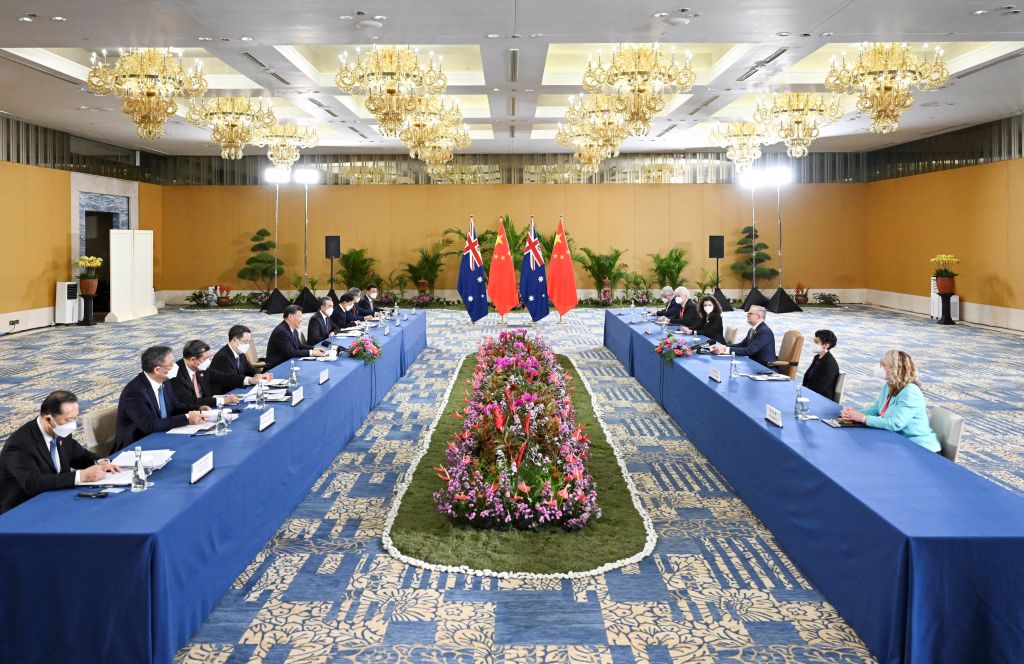

7. Governments should do much more to deter this activity, with costs placed on the Chinese government’s transnational repression by summoning China’s ambassadors and consuls-general to explain the CCP’s disinformation campaigns and ongoing threats targeting these women. For Australia, the government should raise the harmful practice in bilateral meetings with Beijing counterparts—as was done in 2016–17 on cyber-enabled intellectual property theft.

8. Finally, governments need to consider forcing platforms to disclose cyber-enabled foreign interference activity. While there are differences in the content and impact, data-breach notification requirements around the world could provide a template for how policymakers build a system requiring social media platforms to disclose state-backed inauthentic activity on their platforms. While some platforms, including Twitter and Facebook, disclose such activity, others don’t, or do so rarely. But few platforms disclose all activity and many don’t disclose foreign interference in a timely fashion. And, as we’ve highlighted, none invest enough resources in tracking and removing such activity.

Elon Musk has an opportunity to prioritise policy areas such as preventing state-backed information campaigns, disinformation and online harms. But early indications suggest this is unlikely to happen, at least in the short term. Regardless, we cannot rely on any one individual—and the challenge is far greater than any one platform. Too many policymakers and regulators have been overinvested in admiring the problems and underinvested in developing policies to solve them. They must now step up and produce those policies.

While we wait for action, smart Asian women across the globe are being threatened and viciously abused every day by the world’s newest superpower.