The end of the beginning for the Cambodian People’s Party

Cambodia stood between past and future in 2022—balancing completion, new beginnings and legacy creation. As Cambodia’s first electoral term with a one-party National Assembly under the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) drew to a close, the party prepared for an upcoming generational transition.

In December 2021, Hun Manet was endorsed by his father, Prime Minister Hun Sen, and his party as the country’s future prime minister. A photo of what was allegedly 2023’s young incoming cabinet was circulated. The CPP’s key concern in 2022 was to ensure a transition void of surprises. The scions of the old guard slated to become ministers gained public prominence and power constellations settled around them. Manet raised his profile, including as the head of Central Youth CPP, which gained visibility as its members eagerly displayed their allegiance to the successor-in-waiting.

Manet and his wife Pich Chanmony also implanted the idea of themselves as the country’s future first couple through their leadership of the organisation Samdech Techo Voluntary Youth Doctor Association, which having combated the Covid-19 pandemic celebrated its 10-year anniversary.

The imminent end of an era led by the military fighter (neak tosour) generation of CPP leaders also brought in sight the end of Hun Sen’s rule (Samay Decho), which is likely just a few years away.

Hun Sen sought to build a legacy as peacemaker, who through the ‘win-win policy’ defeated and integrated remaining Khmer Rouge forces by 1998. The ubiquitous slogan ‘thank you peace’ (orkon santhepheap), which cast Cambodia’s everyday normality as attributable to and contingent on Hun Sen’s leadership, referred in equal measure to the 2017 dissolution of the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party.

Construction of memorials to honour the ‘win-win policy’ began in Anlong Veng and Pailin, complementing another memorial under construction in Koh Kong, as well as Phnom Penh’s larger monument. On 20 June last year, a commemoration ceremony was held in Koh Thmor X-16, where Hun Sen crossed to Vietnam as a young Khmer Rouge commander to gather forces to overthrow the Khmer Rouge regime.

The area was developed during the year, integrating Hun Sen’s entire political career from 1977 into a longer arch of peacemaking in official historiography. Hun Sen’s receipt of the 2022 Sunhak Peace Prize Founder’s Award, presented in Seoul in February, supported the narrative of the Samay Decho as an era of peace.

The resurrection of the Candlelight Party from the ashes of the Sam Rainsy Party raised the possibility of the return to genuine, though severely limited, electoral competition ahead of national elections that are set to be held in 2023. In commune elections on 5 June 2022, the Candlelight Party won 22% of the popular vote against 74% for the CPP. The election results established the Candlelight Party as Cambodia’s main opposition party.

The ambiguous election results hit a sweet spot, temporarily lowering the risk of party dissolution. In the wake of the elections, the CPP continued to rely on legal strategies to weaken the Candlelight Party—seeking first to dissuade any contestation of election results and second to sever bonds with its popular founder, Sam Rainsy. In parallel, the CPP continued its campaign against the dissolved Cambodia National Rescue Party. Three mass trials were completed, each of which saw dozens of party leaders and activists convicted on conspiracy charges.

Despite, or because of, the stifling political landscape, a labour conflict at Phnom Penh’s NagaWorld casino became a visible disturbance in the capital’s centre—in November, Chhim Sithar, president of the striking union, was re-arrested and sent to pre-trial detention.

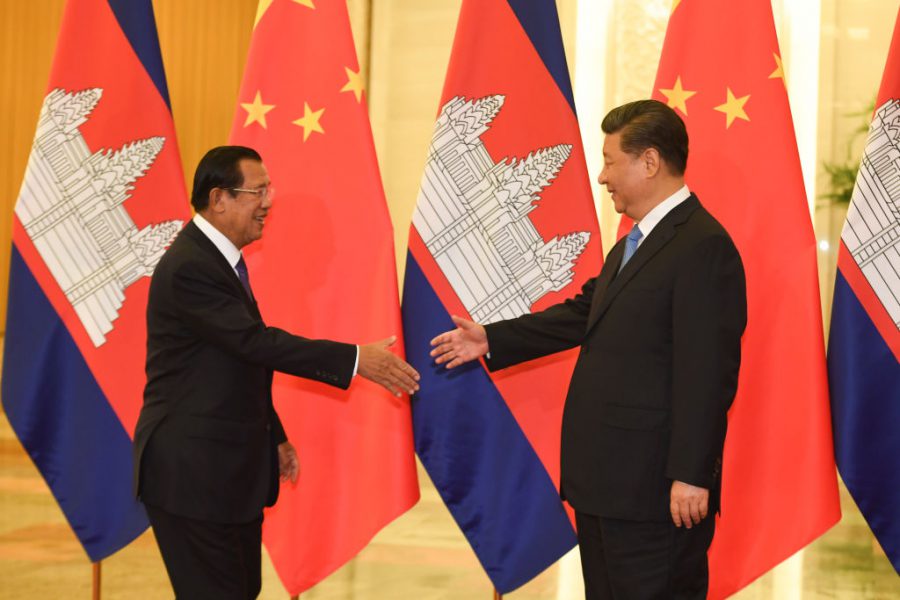

On its third outing as chair of ASEAN, Cambodia pushed for direct engagement with Myanmar’s military government. This was Hun Sen’s attempt to transpose what he considered to be his political legacy of peacemaking onto the global stage. In January last year, Hun Sen was the first head of government to visit Naypyidaw since the February 2021 coup, to push for the implementation of ASEAN’s five-point consensus. But as the year wore on, the junta proved itself impervious to Hun Sen’s masterplan.

Russia’s war in Ukraine brought Hun Sen and his government the recognition they had sought in Myanmar. Surprising all, Cambodia took a pro-Ukrainian stance on the orders of Hun Sen. This earned Cambodia the reinvigorated friendship of Western countries after the chilling of relations that followed 2017’s political crackdown. In December, on a trip to co-chair the first ASEAN–EU commemorative summit in Brussels, Hun Sen was warmly received by French President Emmanuel Macron in Paris—severely undermining exiled opposition leader Rainsy’s claim to the support of the international community.

As the electoral term drew to a close, the feat of the Cambodian government became clear—it had dramatically increased the acceptance and even popularity of what had been an unpopular government over the dissolution of the CNRP at the beginning of its term.

With serious international and domestic challenges absent, the end of the neak tosour era amounted only to the end of the beginning for the regenerated CPP.