Government must rethink funding model to support technology in Australia’s public sector

In the modern economy, all companies are software organisations, whether they realise it or not. So too Australia’s federal government. But how the government works, how it accounts for money and allocates funds, have not kept pace with the modern world of technology—in particular, the integration of data and digital systems in everyday life. That’s not unexpected. Companies, too, are still coming to terms with that world. And our government—through habit and function—is highly risk-averse. As it should be; after all, people depend on it to get things right.

However, the government is also responsible for setting the guardrails for the use of technology by others through policy and regulation.

It matters to citizens and businesses that the government is sufficiently familiar with and experienced in using modern technologies, because that knowledge shapes government policies affecting our wellbeing. That’s why a number of technology companies have offered to brief the Australian Taxation Office on the importance of software development to research.

Just as troubling, outdated technologies and practices increase the vulnerability to attack and the chance of failure of government systems and data—our data. And as technology plays into geopolitics, such weaknesses erode Australia’s strategic posture.

What to do? Let’s start with considering possible changes to the government’s funding of its own technological capability and systems.

The first change must surely be ideational. Governments are inclined to see technology primarily through the lens of efficiency. And over time, technological improvements do lower costs. But that risks missing opportunities to explore new ways of doing business, which often require additional short-term support for long-term gain. Such an approach pinches pennies in terms of the improvements and reserves needed for secure and resilient organisations.

Rather than efficiency serving as the mainstay of arguments for funding, other principles can help set priorities. For example, the focus could be on building government technology and the public service’s skill sets as part of Australia’s sovereign capability; placing people at the absolute centre of decisions—what works for them, what doesn’t—and promoting individual agency; and choosing technologies that best support Australia as a liberal, free-market democracy.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison can take the lead here. He can decide to make such principles a policy mainstay in the upcoming Budget, evidence of action aligned with the recent Quad summit. He can reiterate those principles when writing to ministers in September asking for their proposals for the next Budget. Most importantly, such principles can be embedded in the budget process and operations rules, which are agreed by cabinet each year preceding the commencement of the new budget round.

In short, seeing technology as a broader enabler and not merely a cost-cutter would be empowering. But by itself, that wouldn’t be enough. Alternative principles would still have to compete with the brutal impetus of the efficiency divided (ED) and the offset rule. That’s because money shapes behaviour. And, frankly, the original reasons for both the ED and the offset rule remain: to drive continued efficiencies in government, which has a tendency, for good reasons and bad, to expand; and to exert discipline on ministers who would otherwise spend without saving. However, both policies, as I argued last month, have unintended consequences.

Simply exempting technology programs from the ED wouldn’t prevent cross-subsidisation and cannibalisation, especially when offsets are sought. Nor would it provide an incentive to modernise operations and practices within departments.

Still, there may be options to use both the ED and the offset rule for good.

For example, technology expenditure by agencies could be explicitly broken down into capital expenditure (CAPEX) and operating expenditure (OPEX) components and managed in a similar way to agencies’ administrative budgets. That would give agencies the flexibility to manage funding over the lives of projects and of systems, with similar reporting as for administrative budgets. And any ED savings could then be redirected explicitly to support the transformation and modernisation of core agency operations.

That would enable a virtuous cycle: technology transformation helps generate efficiencies, and efficiency savings help modernise technology to help agencies get smarter at what they do.

Having greater transparency in a technology budget would discourage ministers and portfolio departments from using technology maintenance and upkeep as a means of offsetting new policy proposals. If the government is serious about modernising and securing IT systems, it has to think of technology not as a burden—a cost centre to be harvested—but as an investment that will pay dividends into the future.

And, realistically, redirecting ED savings for technology modernisation alone is unlikely to be enough given the current fragmented, competing and depleted technology stacks, capability and governance across the public sector.

Perhaps the government should consider a separate technology fund, established outside normal portfolio lines, to reduce technical debt, focus on digital uplift, allow coherent security practices across portfolios, and build and manage the underlying sovereign technology asset base for government. A separate funding mechanism or entity could offer scope to innovate and to build the cadre of skilled engineers and social scientists needed to generate those public goods that only the government is well placed to offer.

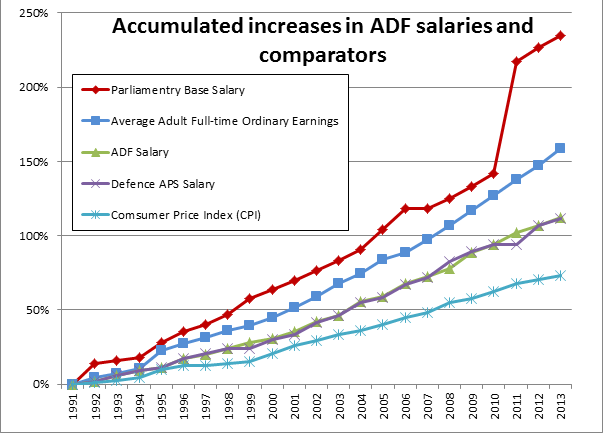

The size of such a fund should not be underestimated. It would need to be big enough to claw back the erosion of assets and capability that have occurred ever since the Gershon reforms to government information technology and the effects of financial framework decisions such as Operation Sunlight, the loss of depreciation funding, the cuts to departmental capital budgets and, most recently, the imposition of the ED on CAPEX.

There is no silver bullet to improve government technology, and here only the funding aspects have been addressed. Nonetheless, given the need to rebuild post-pandemic, if those changes can’t be implemented now, to modernise government systems and services and position the public service for a world of increasing digitalisation and technological competition, then when?