Australia can’t easily lift defence spending to a Trump-satisfying level

US President Donald Trump has called on NATO members to lift their defence spending from the current target of 2 percent of GDP to 5 percent.

‘They could all afford it,’ he said, warning that the United States would withdraw its guarantees of protection to Europe unless they paid up.

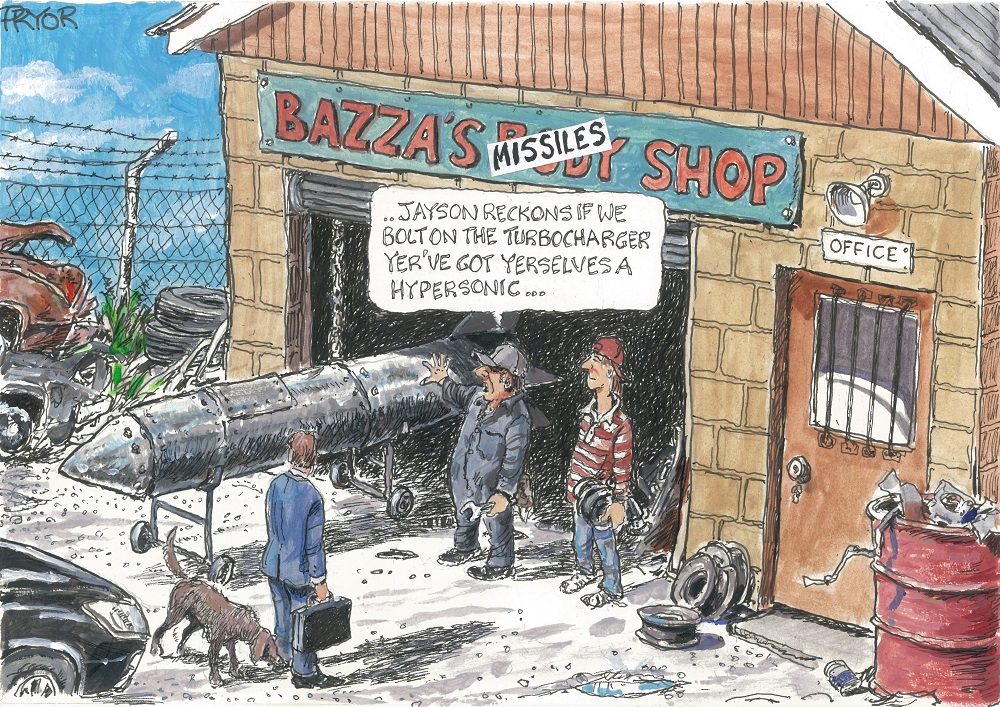

Trump has not opined on Australia’s defence spending, but, when he gets to consider AUKUS, he is unlikely to be satisfied. And there’s no easy way for Australia to lift its spending to a level that would satisfy him.

Australian defence spending was $53.3 billion in 2023–24, which was 2 percent of GDP. The Treasury expects it will reach 2.4 percent of GDP in 2027–28.

Russia, Ukraine, Israel and some Middle Eastern states are the only nations currently spending at least 5 percent of GDP on defence. (China’s data is too opaque to know.) In Europe, Poland comes closest, spending 4.7 percent of GDP this year. US defence spending is 3.4 percent of its GDP.

Trump’s 5 percent figure may be an ambit claim—a Financial Times report suggested he would settle for 3.5 percent. NATO will debate raising its target at its June summit.

For Australia, 3.5 percent of GDP would be $97 billion, about 75 percent more than was actually provided for defence in the budget.

Any increase in defence spending can be funded in three ways: increased taxation, reallocating money from other uses, or debt.

To get an additional $40 billion a year from taxation looks politically painful. To meet that target would require either a 12 percent increase in personal tax collections, a lift in the GST rate from 10 percent to 14 percent, or raising the company tax rate from 30 percent to 40 percent.

The federal government has in fact received an income boost of these dimensions, with total tax collections averaging 23.2 percent of GDP over the past five years, up from 21.6 percent in the previous five. However, this mostly flowed from the extraordinary profitability of resource companies, which will not be repeated.

It is more likely that company tax payments will fall short of treasury forecasts over the next few years as China’s appetite for iron ore and coal fades.

Australia is a low-taxing country—the US, Switzerland and Ireland are the only advanced nations taxing less—so an increase in taxation would not be ruinous to the economy.

It has been suggested Europe impose a defence tax to pay for military preparedness. Denmark scrapped a public holiday to help finance a higher defence budget. Without the immediate threat of Russia at war with a near neighbour, it would be hard to build the political support for such moves in Australia.

Reallocating existing spending looks just as difficult. Cutting social programs carries a high political cost, as the Abbott government learned with its ill-fated 2014–15 budget.

Most of the budget is locked in. There are 412 administered programs with payments governed by indexation. Many programs are driven by legislated entitlements, such as unemployment benefits, Medicare and the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

The NDIS is an interesting example: it elbowed its way into a constrained budget on the false assumption costs would be held to $13 billion a year. Instead, it is at $46 billion this year—1.7 percent of GDP—and is forecast to rise to $93 billion, or 2.1 percent of GDP, by 2033–34.

Strong company tax revenue helped fund the NDIS without resorting to debt until this year. Deficits will increase as resource prices soften and the cost of the NDIS continues to rise three times faster than inflation.

Australia is a low-debt country. Its net debt of 29 percent of GDP compares with an advanced country average of 91 percent, so it could afford to borrow more. Poland has funded its expanded military with debt: its deficit is expected to reach a perilous 12.5 percent of GDP this year. There is pressure to ease the European Union’s debt rules to help lift defence spending.

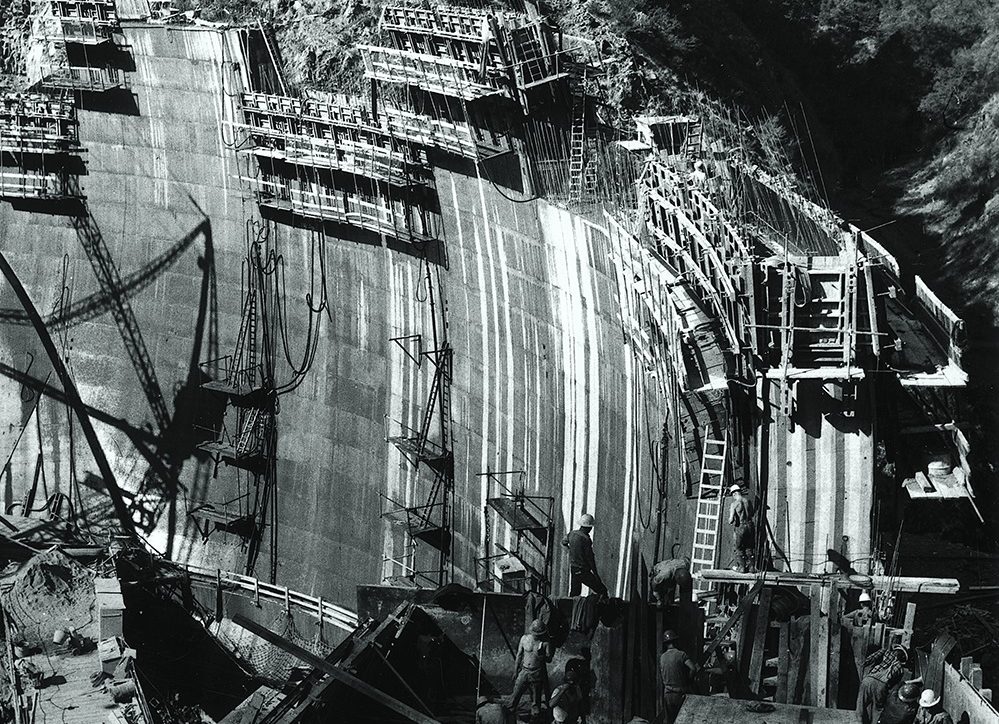

There is an argument for borrowing to purchase assets, including defence equipment, the benefits of which will be derived long into the future. In extreme circumstances, debt forms part of the national security equation through the issue of war bonds.

But with the IMF warning that global government debt is becoming a financial powder keg, surpassing US$100 trillion this year, this may be the wrong time to seek the indulgence of financial markets.

The sorry conclusion is that there is no easy way to achieve the sort of increase in the defence budget that President Trump has in mind for US allies, including Australia.