Beijing drives a Belt and Road between Melbourne and Canberra

The Chinese Communist Party leadership is using the decisions made by the premier of Victoria to engineer a split between the federal government and the states and territories on Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative.

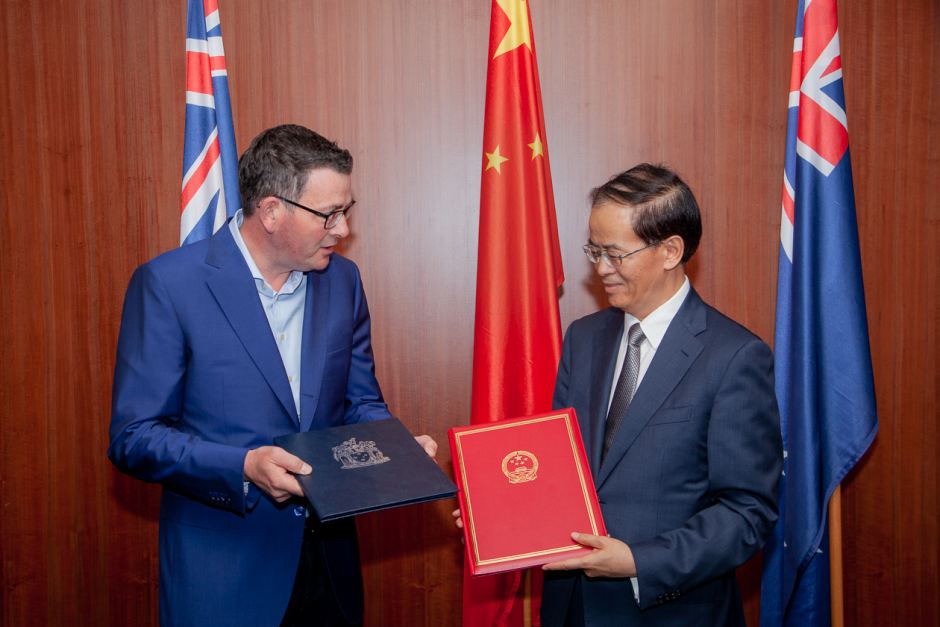

Daniel Andrews announced on Wednesday that Victoria had signed a new deal with China under the BRI that ‘will help fast track cooperation in the key areas of infrastructure, innovation, ageing, and trade development providing more opportunities for Victorian companies and more Victorian jobs’.

The federal government hasn’t signed up to the BRI, saying only that it will consider individual projects on a case-by-case basis. So the CCP has gone around the Commonwealth to see if it can get a different answer from the states and territories, and Premier Andrews has cheerfully obliged.

Foreign investment in Australia is an area in which the federal government’s roles and responsibilities matter—because those roles and responsibilities have led to its not signing up in the way that Victoria has.

The federal government’s areas of responsibility—foreign affairs, defence and national security, including the intersections between them—equip it with agencies and insights that Victoria just does not have. And those constitutional responsibilities weigh heavily when considering an issue like the BRI—because it requires a wholistic perspective that states don’t naturally have, given their different roles and responsibilities.

Andrews has now signed a ‘Framework Agreement with China’s National Development and Reform Commission’, which is the communist state’s former planning commission.

When Andrews signed the original memorandum of understanding on the BRI back in 2018, I wondered what he didn’t know and when he didn’t know it.

Now, I think the conclusion must be that he does know that the BRI is not simply a set of economic investments and projects. It’s also a strategic and technological path to assert the Chinese digital authoritarian state’s power and influence.

Andrews is reported to have said he wants to get more Chinese companies involved in Victoria’s massive $107-billion infrastructure ‘big build’ and to explore cooperation in areas of high-end manufacturing, biotechnology and agricultural technology. This infrastructure build isn’t just about physical infrastructure. Modern infrastructure runs on digital technologies, so Andrews may also be signing up to bring a whole set of Chinese communications, control and collection technologies along with this big build.

And the big build will involve physical and digital critical infrastructure. Both the federal and Victorian governments will need to consider these proposals, not just from the economic perspective that’s clearly driving Andrews, but as a package of security, technology and economic issues—as the federal government did in making its decision on the nation’s 5G network.

Biotechnology is an area that Chairman Xi has highlighted as a source of both strategic and economic power in his ‘Made in China 2025’ agenda, which, like the BRI, is one of Xi’s signature initiatives for making a Sino-centric global order where we all live in the CCP’s ‘China Dream’—along with the people of Hong Kong and Xinjiang.

Andrews’s visits to China to attend Belt and Road forums and to meet with provincial, Hong Kong and Beijing authorities are showing us that Beijing has its house in order when it comes to aligning their positions on key issues like the BRI when they engage with political leaders from other nations. I’d expect to see Beijing reward Andrews somehow, as a way of driving a wedge between the federal and state positions on the BRI and trying to pressure Canberra to change.

It’s not hard for the Australian public or for our leaders to understand this part of Beijing’s agenda, because it’s pretty obvious that it’s a political as well as a strategic move. But it’s a bad look for Australia to have its levels of government played off against each other by a foreign power.

We need to see coordination between the Commonwealth and every state and territory that’s on a par with what Beijing achieves with its other levels of government. We’re not seeing that now.