The battle for the internet

Democracies and authoritarian states are battling over the future of the internet in a little-known UN process.

The United Nations is conducting a 20-year review of its World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS), a landmark series of meetings that, among other achievements, formally established today’s multistakeholder model of internet governance. This model ensures the internet remains open, global and not controlled by any single entity.

This model is now at the centre of a fierce geopolitical struggle. Authoritarian countries are pushing for a multilateral governance approach—one that shifts control of the internet firmly into the hands of governments. This shift would legitimise crackdowns on dissent, expand online surveillance, enable internet shutdowns, weaken human rights, and accelerate the global spread of digital authoritarianism.

Unfortunately, the WSIS+20 review comes as this approach to internet and digital governance is increasingly popular. In recent years China and Russia have made significant inroads in the UN in advancing their interests for greater state control over the internet and digital governance. In 2024, the UN Cybercrime Treaty granted governments new powers over online activity, sparking concerns it could facilitate digital surveillance and legitimise restrictions on human rights and freedoms, while the UN Global Digital Compact also shifted toward a larger state role in digital governance issues.

These developments set a troubling precedent as WSIS+20 unfolds, raising the question of whether the internet remains free and open, or whether the UN will legitimise digital authoritarianism on a global scale.

What is WSIS?

WSIS, held in two phases in 2003 and 2005, was a landmark UN summit that brought the international community together to ‘build a people-centred, inclusive and development-oriented Information Society.’ It established 11 action lines to use information communication technologies for global development and tasked various UN agencies with overseeing their implementation.

In 2005, WSIS’s Tunis Agenda formally established the multistakeholder model of internet governance that had emerged since the internet was created, emphasising the inclusion of governments, civil society, technical experts, academia and the private sector. This recognised that the internet is a network of networks, with multiple stakeholders facilitating its operation. This model—by design—also prevented any single entity, particularly states, exerting undue control or influence over the internet’s architecture. Among WSIS’s achievements was the creation of the UN’s Internet Governance Forum (IGF), a platform where governments, civil society, the private sector, technical experts and academia could engage and collaborate on internet governance issues.

Two decades later, the 2025 WSIS+20 review will revisit established principles and assess progress against the WSIS action lines. The review will consider the extension of WSIS’s mandate, the future of the IGF (whose mandate also expires in 2025) and, potentially, the expansion of WSIS’s mandate to cover emerging technologies such as AI.

The review process has multiple components. UN agencies are conducting reviews of their respective WSIS action lines. The UN Commission on Science and Technology for Development is coordinating input from stakeholders and preparing a report to be released in April. This report will inform negotiations at the UN General Assembly, culminating in a resolution to be presented for adoption by the UN in December. Throughout the year, events such as June’s IGF in Norway (the last before the forum’s mandate expires) and July’s WSIS+20 High-Level Event in Geneva will also provide important opportunities for the multistakeholder community to provide input into the review process before intergovernmental negotiations ramp up.

WSIS and geopolitical competition

With digital technologies playing an ever-growing role in the modern world, the WSIS+20 review is an opportunity to shape the future of the internet and ensure it remains open, inclusive and development-oriented. The aims and ideals of WSIS have never been so important. However, WSIS has become a complicated geopolitical battleground because of its central role in the multistakeholder model of internet governance.

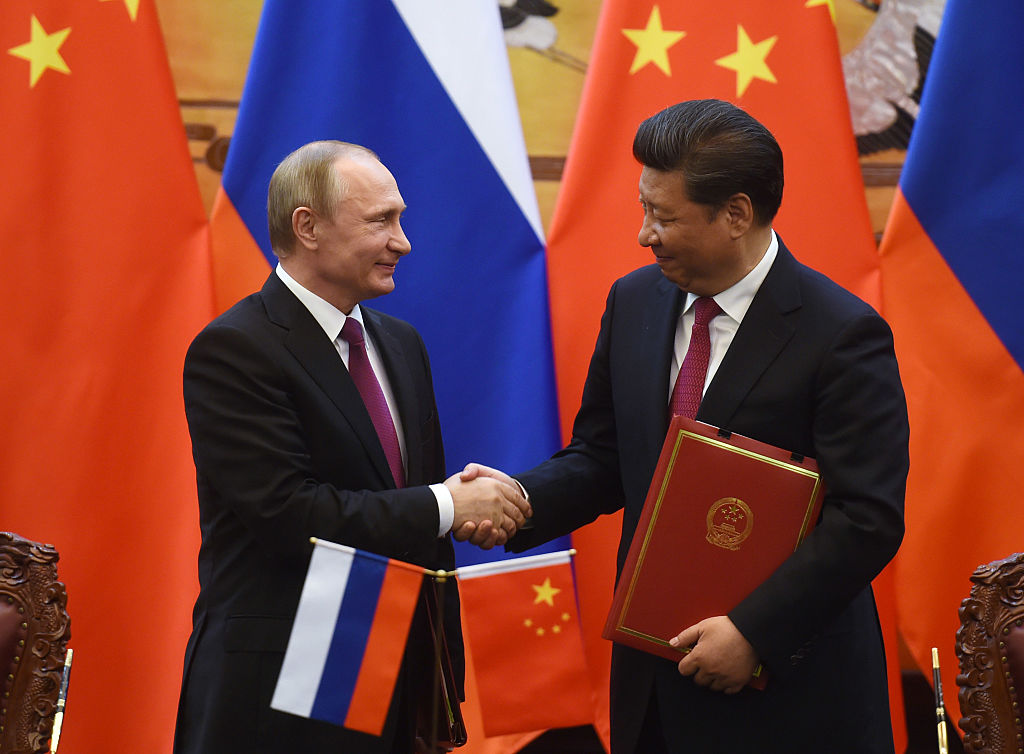

For years, countries such as China and Russia have pushed for a multilateral approach, arguing that internet and broader digital governance should be controlled by states rather than through the multistakeholder model.

Some criticism of the multistakeholder system is warranted. While the model has fostered an open and innovative internet for decades, it has been dominated by Western governments and major corporations, leaving many countries—particularly in the Global South—feeling sidelined in discussions. Its fragmented and complex processes can be difficult and expensive to navigate, limiting meaningful participation. As digital challenges such as AI governance grow more urgent, many countries also see a need for stronger state engagement to protect national sovereignty and counter the unchecked power of Big Tech. Even democracies, historically the strongest proponents of the multistakeholder model, are increasingly drawn to multilateral approaches to rein in tech giants and address digital challenges more effectively.

China and Russia have skilfully and strategically used these criticisms to advance their own agendas, framing multilateralism as a more inclusive and equitable alternative to the multistakeholder model.

However, their push for multilateral governance ultimately serves to entrench authoritarian control over the internet. Both nations promote ‘cyber sovereignty’ or ‘internet sovereignty’ concepts, arguing that states should have absolute control over their domestic internet governance and effectively justifying their digital authoritarian practices.

While their push for increased multilateral cooperation may appear constructive on the surface—multilateral cooperation is normally a good thing—it aims to concentrate power in forums where only nation-states have voting authority, effectively sidelining civil society and other stakeholders. This has serious implications for global human rights and freedoms.

Over the past year, authoritarian states have made significant strides in advancing this multilateral vision within the UN system through processes such as the Global Digital Compact and the Cybercrime Treaty. WSIS+20 is an opportunity for them to consolidate these gains and fundamentally reshape global digital governance in their interests.

What authoritarians want

Authoritarians’ approach to WSIS will likely focus on four broad strategic areas.

First, they will likely push for new initiatives or for inclusion of language that strengthens multilateral cooperation and action, aiming to concentrate power in forums where only nation-states have voting authority, effectively sidelining other stakeholders. This could include attempts to position WSIS as implementing the Global Digital Compact (GDC)—a nation-state negotiated framework—or trying to subordinate WSIS under this framework, despite WSIS’s independent mandate. This could also include attempts to strengthen the newly established UN Office of Emerging and Digital Technologies, an outcome of the GDC. The office has faced controversy over a lack of transparency about its mandate and its potential to not only further centralise internet governance within the UN in New York, but to centre it within the UN secretariat.

Second, they will likely target the IGF. While preventing its extension seems unlikely, authoritarian governments may work to shift its functions to other UN bodies where only states have voting power—a move China has long advocated for. Alternatively, they may seek to weaken the IGF’s effectiveness by maintaining voluntary funding or creating competing multilateral mechanisms that duplicate its functions.

Third, they will likely push to extend WSIS’s mandate to include emerging technologies, particularly through initiatives that emphasise multilateral involvement. This would create opportunities to shape the governance of AI, data, biotechnology and other emerging fields across multiple disparate forums, making it difficult to track developments and coordinate responses.

Fourth, authoritarian states, particularly China, will likely capitalise on WSIS+20’s development-focused agenda. China has promoted the right to development to justify its prioritisation of state-led economic growth over other universal human rights and freedoms, serving as a strategic tool to strengthen China’s domestic authoritarian model in the name of economic progress. WSIS+20’s emphasis on development, and the urgent need to close the global digital divide, creates a risk that this concept could spread to global digital governance. This would provide a framework for other governments to adopt digital authoritarian practices under the guise of national development priorities.

The central role of the Global South in the review process makes this more concerning. China wields considerable influence through this group, including via the G77+China group, which represents 134 of the 193 UN member states—a majority of UN votes if they negotiate or vote as a bloc, as they did in last year’s GDC negotiations.

The structural elements of the WSIS+20 review further tilt the process in favour of authoritarian interests. The outcome document will be presented for adoption by the UN General Assembly’s Second Committee. Beijing has historically wielded significant influence in this forum, increasing the risk that WSIS+20 shifts toward a state-centric model at the expense of the multistakeholder model.

WSIS isn’t happening in a vacuum

While the WSIS+20 review may seem like an abstract UN process, it’s unfolding in a rapidly changing internet and digital landscape.

The internet is becoming less open and less global as national governments—including democracies—assert greater control over digital spaces. Global internet freedom is in decline, with China and Russia advancing their state-centric visions for digital governance—not only within the UN but also through influential groups like BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Meanwhile, China is exporting its digital authoritarian model worldwide via the Digital Silk Road, embedding rules and technologies that entrench state control.

This shift isn’t just happening at a normative or policy level. Technical standards—long an area of geopolitical competition—are beginning to split. The technical foundations of the global internet are also beginning to fracture. For instance, China’s proposed IPv6+ initiative introduces protocols that enable greater state control over internet traffic, raising concerns about its potential global adoption through the spread of Chinese technology.

The internet’s physical infrastructure is also splintering. Subsea cables, telecommunications networks and satellite systems are increasingly fragmented along geopolitical divides. Efforts to decouple technology supply chains—including critical minerals, semiconductors, and advanced chips—are further deepening these divisions.

Conclusion

WSIS+20 is not just another review. It is a crossroads for the future of the internet.

For democracies, WSIS represents the last major opportunity to defend the multistakeholder model of internet governance. Democracies must lead efforts to improve the multistakeholder model, making it more inclusive and responsive to the needs and interests of the Global South with clear ideas about how to harness digital technologies for development. WSIS is an opportunity to genuinely collaborate with these nations to evolve the system and address developmental challenges, all while countering the narratives promoted by authoritarian regimes.

Multistakeholder bodies, such as ICANN, as well as the technical community and civil society, mobilised ahead of the GDC negotiations last year to push back on attempts to erode the open and global internet and shape discussions on how the multistakeholder model could evolve. They are likewise approaching WSIS with the gravity it deserves. Democracies must do the same.

If democracies fail to approach WSIS with the magnitude it deserves, 2025 may well mark the end of the open global internet. The battle for the internet is not just about digital governance- it’s the frontline of the broader struggle over the global order.

Authoritarian states recognise this. It’s time democracies did too.