How a government manages crises is key to curbing the rise of conspiracies

Australia has suffered a litany of crises over the past three years—fires, floods and a pandemic. Crises sap the resources and capacity of government, requiring careful yet immediate management and clear, effective messaging. The way a crisis is managed can have a huge impact on the resilience of the community, as well as on its attitudes towards government. If the government delivers, the confidence of the public can go up; if the government’s efforts seem misplaced or its messaging is unclear, trust in government unsurprisingly falters.

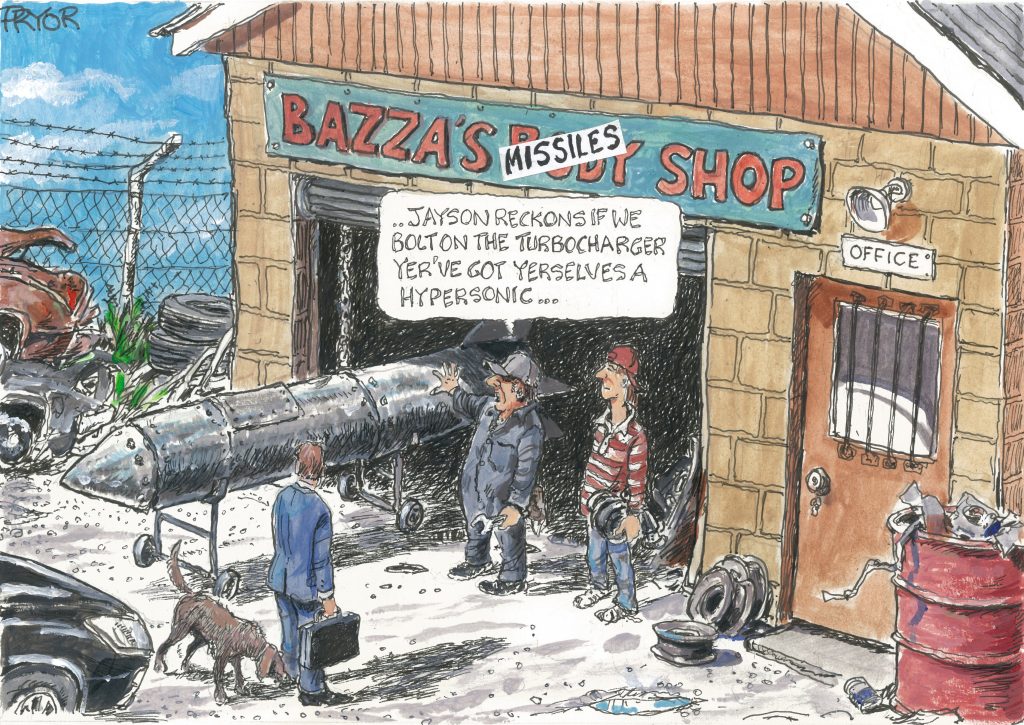

As well as crises, the past three years have also thrown up another challenge—the rise of conspiracy theories. While conspiracy thinking is nothing new, it has reached a level of fervour that poses a real and present risk to the nation’s security. Efforts to counter conspiracies have so far concentrated on independent fact checks and monitoring of foreign influence. While these efforts are steps in the right direction, more must be done to address the individual risk factors for conspiracy thinking—fear, anxiety, isolation and distrust.

The Covid-19 pandemic has been in many ways a masterclass on the relationship between crises, fear and government. Anxiety and fear have been defining factors in the community’s experience of the pandemic, just as they’ve been in the conspiracies that accompanied it.

Studies from the UK have suggested that, regardless of whether an individual complies with health orders or actively undermines them, fear of the virus is the primary motivating factor for both actions. This can put governments in a tricky position, because the dominant source of compliance—fear of the crisis itself—is also a risk factor.

But while fear might be the motivator for action, it isn’t the deciding factor in what people will do in a crisis. In the context of Covid, it was trust that determined what people did with their fear—whether they followed health directives or rioted in the streets. In a nutshell, when it comes to crises, the less people trust a government, the more likely they are to seek alternatives to manage their fears and anxieties. Of course, how effectively a government manages crises, and how clearly it communicates with the people, are themselves deciding factors in public trust.

This means that in a time of rolling crises and pervasive conspiracy, government messaging about and management of crises must be more carefully considered from a conspiracy lens. As outlined in a recent policy paper released by the National Security College at the Australian National University, fear, anxiety, vulnerability and similar conspiracy risk factors must be more effectively incorporated into the government’s calculus when responding to and communicating in disasters and crises.

Government messaging during crises—especially extended ones—should be connected across relevant agencies so that it balances psychological and security considerations. As it stands, security and law enforcement monitor dangerous conspiracy movements for security reasons, while health agencies and mental health professionals monitor conspiracy risk factors.

These two capabilities should be combined by governments when messaging in a major crisis event to ensure that what’s being said doesn’t exacerbate known threats or play into the hands of those peddling conspiracy theories. In the context of Covid, poorly announced news about variants has played into classic conspiracy territory. More recently, reports by officials and the media of a ‘weather bomb’ hitting northern New South Wales assisted the spread of claims that flooding there was the result of cloud seeding.

While it may not be possible to dodge every pothole of conspiracy fears, there are some—such as concerns over child safety or weather manipulation— that are well within the power of government to address.

This combined security and mental health approach can and should be incorporated into law enforcement responses to conspiracy thinking as much as possible. The long-range acoustic devices deployed by police in response to the recent protests in Canberra exacerbated conspiracy fears. If possible, such responses should be calculated to ensure that the benefit of deployment outweighs the possible costs. This is especially important given that, due to the inherent fragility precipitated by a crisis, the effect of any disruption is magnified.

Conspiracy thinking has many causes and considerations that must be addressed on their own terms, not least of which is socioeconomic vulnerability. But while Australia’s string of crises might not be the origin of our most dangerous conspiracy thinking, the way governments navigate crises has a pronounced effect on the prevalence and power those conspiracy theories hold, and the risks they pose to national security.

The Australian government—especially law enforcement, security agencies and emergency services—should develop strategies to ensure that their crisis management and messaging take into account the risk factors for conspiracy thinking. While crises demand quick responses, a bit more consideration can avoid creating two problems out of one.