Digital land power: the Australian Army’s cyber future

Last month, Prime Minister Turnbull revealed that Australia is undertaking offensive cyber operations against ISIS in Iraq and Syria. That followed on from the first acknowledgement that Australia possesses offensive cyber capabilities at the launch of the Cyber Security Strategy in April this year. Both announcements are part of a broader discussion taking place about how Australia should leverage cyberspace to support and enhance its national security and power.

Armed forces around the world are taking advantage of the benefits of cyberspace (as well as defending against the downside risks), and that has implications for the Australian Army. In a context of global competition, Australia can’t be complacent compared with its international peers, particularly those in our nearer region. Military advantages accrue from relative advantages, and Australia must remain cognisant of the collective shift towards sophisticated, connected militaries.

There are notable similarities between the characteristics of earlier electronic and information warfare capabilities and concepts and the challenges and opportunities cyberspace presents to armies. As with previous technologies, cyberspace is used to provide intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance for greater situational awareness and better communication networks for an increasingly accurate shared operating picture. On the offensive, it potentially provides the means to deceive an adversary through misinformation by disrupting their operations. Cyberspace also facilitates information operations more broadly through public messaging activities.

Because of the similarities with previous technological shifts, the big-picture opportunities and challenges of cyberspace for armies could be seen as simply a modern iteration of old dilemmas. But it’d be a mistake to conflate strategic similarities with the assumption that nothing needs to change. Each technology era requires different skills, and the Australian Army must develop new tactics to engage new challenges in pursuit of strategic goals in cyberspace. This idea echoes the Clausewitzian principle: while the nature of war remains the same, its character changes and is determined by ‘the spirit of the age’.

ASPI hosted a roundtable discussion earlier this year to identify the strategic, technological and force structure adjustments that must be made so that the Australian Army can successfully embrace the digital domain. The closed-door discussion between representatives from the Army, the Department of Defence and academia revealed several key issues.

First, at a high level, it’s important for the Army to develop a coherent overarching doctrine for how it’ll approach cyber capabilities. But that long-term process has to be balanced with the ability to quickly implement change and the associated merits of a grassroots “learn by doing” approach.

Similarly, the Army needs to establish clarity around what it wants to achieve through cyberspace. That requires thinking about information assurance, decision-making superiority and information operations value-add that can be delivered through strong cyber capabilities. And the Army’s far from being the only player in this space. Anything the Army does has to be deconflicted with the other services and with broader national and allied efforts through such players as the Australian Signals Directorate.

We won’t get the right strategic effects without the right technology and people for the job. Army’s procurement process is traditionally slow and rigid. Reforming it into a more flexible, iterative process with quicker tech uptake and modular updates will ensure that Army gets innovative technology sooner and isn’t constantly relying on legacy systems. Using commercial hardware and systems architectures could help reduce the impact of slow development and procurement processes.

Then it’s a matter of having the right people to use the gear effectively. The Army currently faces a severe shortage of skilled personnel in a range of technical and professional categories. Attracting and retaining personnel with the necessary skills is essential for ensuring the Army’s ability to achieve its cyber goals. Broadening recruitment profiles, engaging reservists, cooperating with the private sector and academia, and improving the longevity of cyber careers in the Army are vital ingredients in developing a cyber-smart Army.

These key issues are further unpacked in ICPC’s new report, Digital land power: the Australian Army’s cyber future. The report sets out the questions that the Army must consider, and the areas that it may need reform, so that it may reach its cyber potential.

That’s no small challenge for the Army. Fortunately, the current environment is a positive one in which to be implementing daunting cyber reforms, and the money is likely to be there. There’s a convergence of funding from the 2016 Defence White Paper, the Prime Minister’s National Innovation and Science Agenda and the Cyber Security Strategy. The government, private sector and academia are demonstrating increasing interest in cybersecurity, in both their rhetoric and their investments. The Army should take advantage of this opportunity, consider the insights offered in the ICPC’s roundtable report and embrace the reforms necessary to enhance Australia’s digital land power.

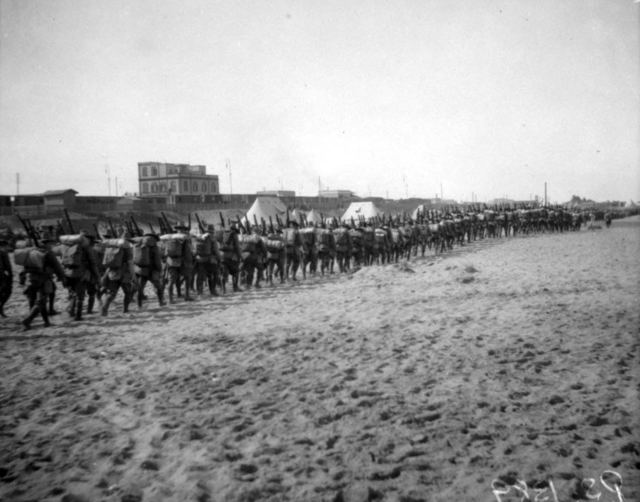

Counterinsurgency is one of the principal modes of conflict of our time. The component of counterinsurgency operations which remains neglected is the capacity building of allied forces—a subject that is rightfully the subject of a great deal of analysis. The ADF has been involved almost constantly with that task for decades, beginning most coherently with the

Counterinsurgency is one of the principal modes of conflict of our time. The component of counterinsurgency operations which remains neglected is the capacity building of allied forces—a subject that is rightfully the subject of a great deal of analysis. The ADF has been involved almost constantly with that task for decades, beginning most coherently with the