Australia’s nuclear-powered submarines will be worth the wait—and the cost

The United States has never sold a nuclear-powered vessel to any nation. In 1958 it transferred technology that enabled the UK to build its own nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs) and ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). Washington’s decision to provide this technology to Australia under the AUKUS agreement is tough, complex and, in some ways, frightening. It reflects a late realisation that the US needs effective allies, particularly in the maritime environment of the Indo-Pacific. Canberra is among Washington’s most trustworthy friends.

The only US ally exempt from its cumbersome International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) is Canada, and that arrangement was briefly suspended in 1999–2001 over doubts about the Canadian security regime.

For AUKUS Pillar 1 (submarines) and Pillar 2 (technologies) to work, the UK and Australia require the same exemption. Australia’s SSN requires more. The US Congress must be convinced that our security systems can be trusted with secrets, and that the boats sold to us will not dangerously deplete US combat capability. This is arguably America’s most important weapons system and one that potential enemies will be unlikely to match.

For Australia this is a long-term program. There’s urgency in our defence situation, but our immediate major tasks are to support American and British submarines rotated through the HMAS Stirling naval base and to train crews, maintenance personnel and construction workers. We hope that deterrence works and those boats don’t have to turn lethal. They will come just in time to replace our six Collins-class submarines as the development of underwater interception capabilities makes the environment lethal for conventional boats.

Submarines are valuable for surveillance, reconnaissance, insertion of special forces, mining and countermining, and to deliver lethal effects at sea using torpedoes and missiles, and, increasingly, on land. Their capacity to remain clandestine and locate anywhere at sea optimises their deterrent value. The conventionally powered Collins boats carry similar weapons, but SSNs have many more of them. SSNs can range over broader areas at greater speed, which heavily complicates the task of any potential enemy. When an SSN has fired a weapon and its general location is known, it can rapidly vacate the zone.

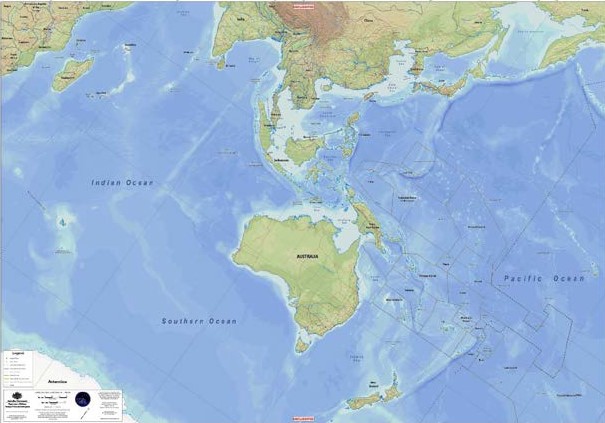

An adversary’s surface warships or submarines have four routes through the archipelago to Australia’s north to reach our waters. A Collins can intercept, but it doesn’t have the speed to follow. An SSN has that speed and it can reposition rapidly if necessary. Our military capabilities on the surface or on land can potentially be targeted but SSNs cannot. That’s why the government sees their essential deterrent value. We have no equivalent. The defence minister is constantly being asked why we must have SSNs despite their high cost. The $369 billion over 30 years is a bagatelle compared with what we will spend on the National Disability Insurance Scheme and many other social programs over that period.

This is the essence of our deterrence: a heavy weapon that can hit targets on land and sea. Previously that was the role of the F-111 bomber. Years ago my Indonesian defence counterpart, the late General Beni Moerdani, told me that when those around the cabinet table with him were angry with Australia and inclined to do something about it, he would remind them that Australia had an aircraft that could put a bomb through a specific window. That capability is effectively restored by SSNs—and the delivery system can’t be seen.

Australia won’t have its first SSN for 10 years. The beginning of the program is the most fraught, but it will be challenging throughout. The plan is to fold the AUKUS bills in Congress into the US National Defense Authorization Act. One of the plan’s strongest supporters, Democratic Representative Joe Courtney, tells me the Senate still hasn’t appointed conferees for this process. The House has. Conference is how disagreements between the Republican-controlled House and the Democrat-controlled Senate are rationalised. The House Foreign Affairs Committee backed the plan 48–0. In the Senate, Republican Roger Wicker has put a hold on it. He wants from the president a full industrial base plan before supporting the sale. That isn’t necessary and the industrial build-up is proceeding at pace.

The question for Wicker and others is not whether Australia should have SSNs but whether a target to get 66–69 SSNs in the US inventory can be reached if we get ours. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of boats delivered drop to 1.2 a year when 2.3–2.5 is necessary. Available numbers dropped to 60% because of maintenance challenges. It is now back to 67% and SSN production has climbed to two per year. The US Navy wants 80% available and believes that can be reached by 2028.

The US has almost finished building Block IV Virginia-class SSNs, the version we want. A much bigger Block V version is now the focus. It has a substantially larger number of vertical launchers for cruise missiles with ultimately a hypersonic missile version. This capability replaces the launchers in four soon-to-be-paid-off converted SSBNs.

This month a five-year industrial agreement between submarine builder Electric Boat and its 3,400 skilled employees was completed. The agreement incorporates a substantial wage rise, retention bonuses, a lift in retirement savings, a comprehensive medical plan and increases in vacation and sick leave. These conditions also apply to the 5,000 workers the company has been trying to recruit this year. It reached 4,000 in August. It is also outsourcing production to other companies, with assembly in the main yards. Americans can do things quickly when money and workforce are available. Joe Biden’s administration will need to convince doubters and the $3 billion Australia is putting in is proving useful in discussion in Congress.

Exemption from ITAR is critical. I thought that had been achieved in 2010 when we and the British negotiated the Defence Trade Cooperation Treaty which ratified a 2007 agreement between George W. Bush and John Howard, but it fell short of the Canadian exemption.

ITAR makes cooperation with US companies difficult because, if a good product is developed, sales to third countries may be blocked. The US is deeply concerned about Chinese intelligence capabilities. The director of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, Mike Burgess, noted that after AUKUS was announced a massive Chinese espionage effort was detected aimed at Australian government, industrial and educational entities.

Defence News says a strong effort is being mounted in the administration and Congress. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee recommended a different approach to ITAR reform which scooped us up, and that has passed the Senate 86–11 as an amendment to the 2024 defence policy bill. Kurt Campbell, National Security Council coordinator for the Indo-Pacific, said this was not ‘whether to’, but ‘how to’. The State Department has also established an AUKUS trade authorisation mechanism as an interim capability to speed up technology transfer.

The Americans have identified areas including quantum computing, artificial intelligence and hypersonics where our research is ahead of theirs. Anthony Di Stasio, who oversees Defence Production Act grants, has suggested Australia would help bolster US supply chains for critical minerals like cobalt and explosive materials like TNT.

We need patience. The American decision-making environment is complicated. We know how to work it but we can expect much frustration. We can only hope that our diplomatic skills and those of our allies prevent a major conflict in our region while we restructure.

Events in the Middle East and Ukraine may divert attention when we need intense US legislative concentration on the AUKUS issues, but we have time. No SSNs are due until the 2030s and, in the meantime, the structures to support rotating allied forces are relatively easy to establish. The future crews can be trained on allied boats. The capability is worth the effort.