Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

AUKUS Pillar 2 has a PR problem—and no, not just among sceptical regional partners.

Compared with evident progress on Australia’s future submarine capabilities under Pillar 1, analysts have often decried a lack of detail or engagement around Pillar 2, which is aimed at wider defence-technology cooperation. Despite efforts to spotlight trilateral innovation activities in the past 12 months, the absence of clear metrics for success, let alone a shiny new trilaterally developed capability carrying an AUKUS sticker, have led some to contend that Pillar 2 is falling short.

This has contributed to skewed assumptions about what constitutes success for Pillar 2. On closer inspection, Pillar 2 is actually making substantial progress, both in necessarily preparing the field for future cooperation by harmonising regulatory and policy settings and by maximising operational efficiency and interchangeability of advanced capabilities already in service.

The problem is that these activities have, until now, not been cast as key outputs or essential waypoints in the service of operationalising Pillar 2 projects.

Perceptions that Pillar 2 is falling short understandably frustrate those within the Australian strategic policy community seized by a sense of urgency. Compared with the long lead times for Pillar 1, officials and analysts alike have framed Pillar 2 as a means to accelerate the delivery of advanced capabilities to the military over a much shorter period, particularly within the next five years. But for many, this is contradicted by an apparent lack of ‘new’ material output in nearly two-and-a-half-years and a growing to–do list. Many members of the policy community have also bemoaned a lack of official information about Pillar 2’s innovation functionality objectives or the barriers to setting the enabling environment.

The perception that Pillar 2 would deliver trilaterally developed advanced capabilities on an accelerated timeline has led to inflated expectations about what it should, and could, achieve in the short term.

On one level, this may be attributed to the lack of information or insight from the AUKUS governments about what has been happening in the Pillar 2 space. Yet, since as far back as 2007, policy communities in all three countries have understood many of the challenges and barriers to defence industrial base integration and technology co-development.

In that context, the essential institutional reforms and regulatory harmonisation efforts that are now in train in Australia, Britain and the US should be considered legitimate outputs of Pillar 2, particularly in its infancy. If AUKUS represents a revolution in defence industrial and technology collaboration amongst allies, then Pillar 2 is as much about setting the conditions for more streamlined cooperation on advanced capabilities as it is about the specific capabilities themselves. Properly sequencing these activities is essential in order to avoid revisiting known problems every time a new trilateral innovation project is launched.

This is how the three governments appear to be conceptualising of Pillar 2: as a scalpel for dissecting institutional barriers to trilateral co-innovation. Hugh Jeffrey, Australia’s deputy secretary of defence for strategy, policy and industry, intimated as much during a recent CSIS event on Australia–US defence industrial cooperation. That this logic has now been stated publicly helps to recast reform efforts as a core mandate of Pillar 2, rather than simply a hinderance to its success or evidence of its stagnation.

In that respect, it’s possible to imagine an innovation lifecycle model for AUKUS Pillar 2 with three phases: reforming processes and sharing best practices, coordinating innovation and technology adoption, and near-seamless co-innovation.

The first phase is about harmonising export controls, progressing conversations about foreign disclosure, procurement policies, information-sharing and certification systems, but also limited innovation activities centred on data-sharing, capability demonstration, and building interoperability. This has included activities such as aligning common artificial-intelligence algorithms on P-8A maritime patrol aircraft to improve data processing for trilateral anti-submarine warfare activities.

The second phase focusses on coordinated innovation, whereby governments simultaneously conduct innovation challenges on an agreed theme but within their national contexts. An example is the AUKUS electronic warfare innovation challenge, announced in March 2024. Australia’s 2024 National Defence Strategy suggests that this phase may also include the trilateral adoption and delivery of novel technologies developed by any one of the partners.

Once these conditions are set, Pillar 2 could progress to a third phase and ideal end-state—genuine trilateral co-innovation and co-imagination.

This three-step model helps to situate the activities and progress publicly disclosed to date in a broader context. It is also one that resonates with experts well-versed in AUKUS Pillar 2 policy discussions in all three countries with whom we have recently engaged.

Given the long-standing barriers to technology cooperation between even the closest of allies, it’s unsurprising that initial Pillar 2 outputs have focused on reforms to the enabling environment and on maximising the operational efficiency and interoperability of priority capabilities. While co-innovation and co-production might be the gold-standard for AUKUS Pillar 2, progress in that area is not a realistic metric to measure success in the short-term.

To solve Pillar 2’s two-pronged PR problem—limited information and over-hyped expectations—the three partners should further clarify the logic and importance of this scalpel strategy and the sequencing of the innovation lifecycle. This will help to not only keep industry and innovation stakeholders engaged and supportive, but also balance expectations about what is possible within what timeframe.

Although Pillar 2’s end goal is more ambitious than what we have seen to date, it was always going to be a challenging first step to set the enabling environment for future success and to maximise possibilities for co-innovation within current limitations. Going forward, clearly communicating Pillar 2’s necessary sequencing to the right audiences on an appropriate timeline is critical, as is an appreciation by other AUKUS stakeholders of the complexities of the bigger picture.

The Australian government is embracing a whole-of-nation approach to international policy. This means that, in enhancing international engagement, it wants to use resources across society—beyond core international policy actors, such as the departments of Defence and Foreign Affairs and Trade. The idea includes using input from business and investment, science and technology, education, sports, culture, media and civil society.

But how, in practice, is this to be done? That’s still not entirely clear. Much like conventional notions of statecraft, a whole-of-nation approach is easier in theory than in practice. The effort to organise and harness the country’s distinct and sometimes competing interests, with all their complexity and contradiction, is immense.

Central to a whole-of-nation approach is an elevated, enhanced and collaborative form of leadership. If governments wish to marshal, guide or direct, first they need to explain, persuade and inform. These are significant new tasks that core international policy actors may not now be equipped or resourced for. This is addressed in a new report from the Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy & Defence Dialogue (AP4D).

To develop a whole-of-nation foreign policy strategy, Australia must look to build upon successful examples. Cross-sector cooperation in foreign policy is already in action and there are examples that provide models and lessons that can be replicated.

One was the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup, in which different parts of society and government worked together to build the country’s international profile. Australia used the tournament to engage with foreign partners through sport, benefitting sectors including media, trade, education and tourism.

Businesses engaged through global partnership deals with FIFA, and the knowledge and education sector became involved through universities and think tanks that researched issues impacting women’s sport. The community, including significant diaspora engagement, contributed to the biggest successes of the tournament: filled stadiums and broken television viewership records.

Building on examples such as this, there are more opportunities for Australia to implement a whole-of-nation approach.

One example for the future is exploitation of Australia’s significant deposits of critical minerals, including cobalt, lithium, manganese, tungsten and vanadium. These minerals are necessary for emerging technologies that future economies will rely on, underpinning the renewable energy transition. The development of new critical-minerals supply chains has also serious implications for Australia’s security partnerships, particularly AUKUS.

Considering the importance of the emerging critical-minerals industry, the federal government must play a prominent role in bringing together stakeholders to advance industry capabilities. Australia can position itself as a trusted and reliable supplier of both raw and processed critical minerals while also seeking opportunities as a manufacturer in renewables technology.

It can’t be done without coordination between government, industry, science, education and civil society—in other words, a whole-of-nation approach.

Similarly, there is a need for Australia to take a whole-of-nation approach in its bid, in partnership with Pacific island countries, to co-host the 2026 Conference of the Parties of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP31). The bid requires alignment of domestic policy with foreign policy goals; it can hardly be done by the Department of Foreign Affairs alone.

COP31 will require Australia as a nation to deliver on its climate commitments. Co-hosting with the Pacific will ramp up pressure to phase out fossil fuel production in support of the Pacific’s fight against climate change. A whole-of-nation approach to COP31 will be an opportunity for Australia to ensure that what it stands for internationally—strong action on climate change—is backed by a domestic climate action agenda. A whole-of-nation approach to COP31 will allow Australia to restore its reputation internationally as a climate leader and strengthen its standing in the Pacific as a credible partner.

Recognising that different groups will have specific interests in different components of Australia’s international statecraft, the whole-of-nation approach should focus on identifying the complementary nature of various resources and groups. By doing this, the government sends strong signals to civil society and the private sector about what their contributions can be.

The government should promote the whole-of-nation concept without imposing a centralised top-down approach to international engagement. The idea should begin with a set of values and interests with which any number of actors can align.

Underpinning this, there will need to be effective structures, coordination mechanisms and resources that support and empower different parts of Australian society to participate in contributing to foreign policy goals. Australia can seek to broaden how it approaches the world by establishing frameworks and guidelines for how multiple groups can contribute to the national interest.

Not everyone will be in full alignment on all issues. So a whole-of-nation approach must value diversity and continuously shifting consensus while recognising that Australia is stronger internationally if it has a common voice.

As Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong recently remarked at the launch of an AP4D report on a whole-of-nation approach to international policy: ‘We need to coordinate our strengths …. It’s not just up to our diplomats, nor our military alone. It starts with who we are as a country: our First Nations history, our multicultural fabric, our institutions, business, academia, and civil society’.

This article draws on AP4D’s report on What does it look like for Australia to take a Whole-of-Nation Approach to International Policy.

The Australian government is embracing a whole-of-nation approach to international policy. This means that, in enhancing international engagement, it wants to use resources across society—beyond core international policy actors, such as the departments of Defence and Foreign Affairs and Trade. The idea includes using input from business and investment, science and technology, education, sports, culture, media and civil society.

But how, in practice, is this to be done? That’s still not entirely clear. Much like conventional notions of statecraft, a whole-of-nation approach is easier in theory than in practice. The effort to organise and harness the country’s distinct and sometimes competing interests, with all their complexity and contradiction, is immense.

Central to a whole-of-nation approach is an elevated, enhanced and collaborative form of leadership. If governments wish to marshal, guide or direct, first they need to explain, persuade and inform. These are significant new tasks that core international policy actors may not now be equipped or resourced for. This is addressed in a new report from the Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy & Defence Dialogue (AP4D).

To develop a whole-of-nation foreign policy strategy, Australia must look to build upon successful examples. Cross-sector cooperation in foreign policy is already in action and there are examples that provide models and lessons that can be replicated.

One was the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup, in which different parts of society and government worked together to build the country’s international profile. Australia used the tournament to engage with foreign partners through sport, benefitting sectors including media, trade, education and tourism.

Businesses engaged through global partnership deals with FIFA, and the knowledge and education sector became involved through universities and think tanks that researched issues impacting women’s sport. The community, including significant diaspora engagement, contributed to the biggest successes of the tournament: filled stadiums and broken television viewership records.

Building on examples such as this, there are more opportunities for Australia to implement a whole-of-nation approach.

One example for the future is exploitation of Australia’s significant deposits of critical minerals, including cobalt, lithium, manganese, tungsten and vanadium. These minerals are necessary for emerging technologies that future economies will rely on, underpinning the renewable energy transition. The development of new critical-minerals supply chains has also serious implications for Australia’s security partnerships, particularly AUKUS.

Considering the importance of the emerging critical-minerals industry, the federal government must play a prominent role in bringing together stakeholders to advance industry capabilities. Australia can position itself as a trusted and reliable supplier of both raw and processed critical minerals while also seeking opportunities as a manufacturer in renewables technology.

It can’t be done without coordination between government, industry, science, education and civil society—in other words, a whole-of-nation approach.

Similarly, there is a need for Australia to take a whole-of-nation approach in its bid, in partnership with Pacific island countries, to co-host the 2026 Conference of the Parties of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP31). The bid requires alignment of domestic policy with foreign policy goals; it can hardly be done by the Department of Foreign Affairs alone.

COP31 will require Australia as a nation to deliver on its climate commitments. Co-hosting with the Pacific will ramp up pressure to phase out fossil fuel production in support of the Pacific’s fight against climate change. A whole-of-nation approach to COP31 will be an opportunity for Australia to ensure that what it stands for internationally—strong action on climate change—is backed by a domestic climate action agenda. A whole-of-nation approach to COP31 will allow Australia to restore its reputation internationally as a climate leader and strengthen its standing in the Pacific as a credible partner.

Recognising that different groups will have specific interests in different components of Australia’s international statecraft, the whole-of-nation approach should focus on identifying the complementary nature of various resources and groups. By doing this, the government sends strong signals to civil society and the private sector about what their contributions can be.

The government should promote the whole-of-nation concept without imposing a centralised top-down approach to international engagement. The idea should begin with a set of values and interests with which any number of actors can align.

Underpinning this, there will need to be effective structures, coordination mechanisms and resources that support and empower different parts of Australian society to participate in contributing to foreign policy goals. Australia can seek to broaden how it approaches the world by establishing frameworks and guidelines for how multiple groups can contribute to the national interest.

Not everyone will be in full alignment on all issues. So a whole-of-nation approach must value diversity and continuously shifting consensus while recognising that Australia is stronger internationally if it has a common voice.

As Minister for Foreign Affairs Penny Wong recently remarked at the launch of an AP4D report on a whole-of-nation approach to international policy: ‘We need to coordinate our strengths …. It’s not just up to our diplomats, nor our military alone. It starts with who we are as a country: our First Nations history, our multicultural fabric, our institutions, business, academia, and civil society’.

This article draws on AP4D’s report on What does it look like for Australia to take a Whole-of-Nation Approach to International Policy.

As it prepares Australia to defend itself in a contested region, the ADF has put the call out to young people to join—to achieve its goals, it needs to recruit 18,500 more people of serving age by 2040.

Young people in Australia can seem an enigma to marketing minds and the labour market is no exception. Specifically, recruiters are neglecting a rapidly growing phenomenon affecting many Australian young people—mental illness.

Not only are distressed young people less likely to do something as difficult (if rewarding) as joining the armed forces than if they were feeling well, but they are also actively barred from exploring this option. According to Defence’s supplementary submission to a Senate Standing Committee on suicide prevention among veterans—a ‘current psychiatric condition’, defined by diagnosis in the last 12 months, is currently an exclusion condition in a defence force recruiting process.

But here’s the issue, 4.2 million people meet this criteria, according to the National Study of Health and Wellbeing conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. And with the ADF hoping to get more women into uniform, it’s especially concerning that 24% of females surveyed in that study met this exclusion criteria.

And even this understates Defence Force Recruiting’s woes. These numbers are even worse among its biggest target market—young people.

Among those aged 16-24 years, almost two in five (39.6%) had an ‘active’ mental health diagnosis in 2020-21.

For females in this age group, that number soared again, to almost half (46.6%). As it stands, this exclusion criterion makes more than a third of young Australians unable to serve in the ADF.

Defence Force Recruiting likes to paint life in the army as exciting and one of a kind. Announcing their recent campaign, ‘Live a story worth telling’, a leader described Defence personnel’s lived experiences as ‘filled with laughter, joy, sometimes tears and excitement.’

While this is certainly true for some members, and no two experiences of any career are the same, it only tells one side of the story. Defence needs to be more transparent about the psychological difficulties members can face during and after their careers.

The 2021 National Health Survey shows that Department of Veterans’ Affairs clients are twice as likely as non-clients to experience an anxiety disorder. Suicide rates for ex-serving members of the armed forces were 24% higher for ex- males, and 102%, or roughly twice as many deaths per 100,000 people, for ex-serving females.

The ADF’s own mental health prevalence report into health and wellbeing transition estimated that 46% of transitioned ADF members had experienced mental illness in the previous 12 months in 2015.

To address this, the ADF is responding with several initiatives designed to identify changes in the mental health of members. However, these reports focus primarily on prevention, rather than management and treatment. They contain extensive discussion of ‘building resilience’.

In 2019, the ADF released a report that said, ‘Lower levels of resilience, as measured by the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), have been linked to attrition from the military and being diagnosed with a mental health condition in the early years of military service’.

Whether resilience is a useful way of viewing mental health prevention or not, identifying those who are diagnosed with a mental health condition as ‘lacking resilience’ is absolutely out of touch with the approach of Australian young people. Indeed, it’s at odds with the approach of many mental health professionals.

Even if preventing mental health issues is possible through ‘building resilience’, focusing heavily on prevention without addressing treatment can’t work at scale, assuming current trends among young people will hold. The ADF faces a massive mental health challenge.

With young people entering the ADF every year, Defence must address the growing risks of those with psychological distress entering service. It needs to shift its approach and better help members manage and be willing to help treat low-risk mental illnesses among members, not only prevent them. It can’t only rely on resilience, awareness-building, and exclusion from service. It’s also worth noting that the ADF’s own reports show that exclusion from service itself is a high-risk factor among members that have issues later in life.

It’s far too late to prevent the mental health epidemic tearing through the Australian people from reaching the ADF. As Defence builds its workforce in coming years, it will need to deal with members being mentally unwell—often temporarily, when well-treated—at a growing rate.

To meet its ambitious targets, Defence needs a recruiting strategy intelligently targeted at young Australians. This means going beyond platitudes about resilience and expanding the ongoing treatment of low-risk mental health disorders in the ADF. This means acknowledging that a large portion of potential candidates, perhaps eventually most, have faced some kind of mental health issue. Like it or not, some people who need treatment are going to end up in service.

There was a time when mild asthma excluded a candidate for service. Eventually, the ADF came to realise that low-risk cases could be managed, introduced a system for members who suffer from it, and relaxed this requirement.

In a strategic environment that demands a surge of participation from young Australians to make their country safe, having sought help for mental health shouldn’t be seen as any different.

The Australian government’s proposed amendments to the Defence Trade Controls Act 2012 have provoked strong reactions. Debate on this issue has been simmering for some time, mostly remaining under the mainstream radar. The short window for feedback on the proposal risks pushing the debate to the point of hyperventilation.

Critics denounce any attempt to tighten the rules. Some are worried that Australia is unwittingly relinquishing its sovereignty and caving to the demands of an overbearing partner (which has, not without irony, the dubious honour of running one of the most outdated, onerous and poorly implemented export-control regimes in the Western world).

But a closer look at the details of the amendments reveals that they present an unprecedented opportunity. Capitalising on that opportunity means getting the rules right and ensuring that the Department of Defence has the capacity and the capability to implement them skilfully.

The amendments intend two primary effects. First, they would expand the scope of export-control regulation to include foreign persons within Australia, re-exports to third countries of previously transferred technologies, and services related to technologies included on part 1 of the defence and strategic goods list. Second, they would provide an exemption on permits for exports to the US and UK of certain technologies.

Without doubt, Australia shouldn’t mimic the US’s International Traffic in Arms Regulations. A Cold War relic, ITAR has for decades been a great wet blanket thrown over the Western defence innovation enterprise. Approval timelines are lengthy, to the point of being prohibitive for many small and medium-sized companies that are highly sensitive to cashflow fluctuations. Incentives are misaligned, with administrative responsibility assigned to an organisation without a dog in the fight and an actor-agnostic mindset. Effective risk management is stifled by the worst characteristics of bureaucracy.

The proposed changes to Australia’s rules would indeed make them look a bit more like ITAR. Greater alignment is necessary to realising the aims of the AUKUS pact. But they wouldn’t increase the degree to which Australian businesses are subject to US dysfunction (except in terms of sales volume, a mooted benefit of the new regime). In fact, the amendments can change the terms of the debate. If properly designed and administered, they can create a new source of competitive advantage for Australia.

The problem with ITAR is not its underlying principles. Defence technology must be tightly controlled. Defence innovation is useless—indeed, actively harmful—if its output is readily available to geopolitical competitors. Private companies may not like heavy-handed regulation, but it is a cost of doing business in defence markets.

The effect of Australia being exempted from ITAR without tightening its own defence export controls would be to open the drain on the massive bathtub that is the US defence industry. Loopholes would be obvious and easily exploitable by opportunistic and malign actors alike. That the administration of the US rules has often been ham-fisted doesn’t change this basic fact.

But there’s more to the proposed legislation than tightening the rules. Examine the underlying economic incentives, and it becomes apparent that alignment of AUKUS export-control regimes could have significant positive long-term effects. The US has voiced commitments to open reciprocal exemptions for AUKUS partners meeting a standard of protection. Expanding the size of the yard to include alternative regulatory environments fundamentally changes the incentives for ITAR administrators. It sets a price on dysfunction.

Should the amendments be enacted, barriers to trade would decrease for Australians wishing to sell controlled technologies to the US and the UK. This would also apply to US and UK businesses that decide to move their research and development activities to Australia. They would maintain unfettered access to home markets. Intellectual property created in Australia would be subject not to ITAR, but to the Australian export-control system.

Competition changes everything. The price of sclerosis in the US system will be businesses choosing to move their R&D elsewhere. Until now, there has been nowhere to move without sacrificing the largest defence market in the world. Under the AUKUS partnership, that will no longer be the case.

All this, of course, is not a free pass for Australia. Entering the competition doesn’t mean we’ll win. The design and management of the export-control system will be vitally important. Australian regulators must provide an unimpeachable level of protection for defence-related technologies while avoiding the pitfalls that tripped up our longstanding ally.

How do the proposed changes stack up in this regard?

First, the amendments don’t account for the disruption they will cause to existing partnerships. Ongoing work must be grandfathered under the new regime. Those affected should be asked to submit commitments to align their practices with the new rules over a reasonable period.

Under the proposal as currently written, a companies could incur criminal penalties for breaking the new rules when they become active in 12 months. That could slam the brakes on the Australian defence industry. The small and medium-sized enterprises on which it depends don’t have armies of lawyers standing ready to facilitate the transition. The amendments must apply a phased approach, introducing an intermediate period in which civil rather than criminal penalties apply.

The administrative burden of compliance is manageable for larger companies and prime contractors. It is absorbed as a cost of doing business. But that is often beyond the capability of smaller firms. A grant program should be established to assist small and medium enterprises with compliance paperwork and legal advice. This is a small cost for significant industry-wide potential gains. An application process should be set up to enable Defence to direct assistance where it is most needed.

Expanding the scope of the export-control regime will also increase the workload on administrators. The amendment takes no account of this, postponing an analysis of the financial impact until the next budget cycle. Winning in the new competitive environment will demand smooth functioning of administrative processes. Permit-processing delays resulting from an understaffed administration will set Australia on a path to assuming all the worst aspects of ITAR. We need immediate investment in administrative capacity and technical expertise. A permanent body must evaluate and monitor performance, including all associated governance, audit and resourcing functions.

Risk-management standards must deliberately account for varying levels of trust in export-control regimes beyond the AUKUS partnership. The rules should acknowledge third-party arrangements and adjust the stringency of export-control reviews based on the regulatory environment of the recipient.

The legislation must include a sunset mechanism for future application of Australian law to exported and re-exported articles. The period over which such a sunset clause applies will vary depending on the technology in question and should be assessed at the time of export approval.

Finally, the innovation ecosystem depends not just on defence-related hardware, but on collaborative relationships between Australian innovators and their foreign partners. Innovative activities incorporate dynamic networks of experts. These networks can’t be fully specified in advance. Export-control legislation must include expedited approval processes for bringing additional partners into previously approved technology-transfer relationships.

AUKUS presents an unprecedented opportunity for Australia. It has the potential to shake up a legacy export-control system that has become an impediment to defence innovation the world over. Previous attempts have failed due to the lack of a compelling political imperative and strategic drivers. AUKUS has the potential to introduce a new source of Australian competitive advantage that will draw in innovative activities and all the economic spillovers that come with them.

The devil is in the details.

Australia hasn’t been truly sovereign in its own right since 1788. The head of state remains a foreign monarch. Generations of Australians have been lulled into forgetting this reality by the cultural familiarity of the Anglosphere. Australia only exists within a postwar rules-based order, and, conversely, without Pax Americana, Australia as we know it wouldn’t exist. Concerns about loss of sovereignty arising from AUKUS are illusionary. We’ve never really had it.

AUKUS requires a clear-eyed assessment of Australia’s sovereignty ambitions. Functioning sovereign states require the resources to defend their interests. Security analysts tend to express these capabilities mechanically, typically in terms of military force structures comprising ships, submarines, planes, tanks, infantry battalions, and so on. Capability gaps are identified in the acquisition, transitioning or sustainment of platforms. However, arguments for future force structure can’t be made in a vacuum. They must be cost conscious and restrained by the available human resources. In Australia’s case, the foremost future capability gaps will be in people, not machines.

The ANZUS Treaty singularly illustrates Australia’s strategic security team. Despite Donald Trump’s presidency forcing many Australians to confront for the first time a shocking cultural and values misfit with the leadership of their country’s major partner, the AUKUS agreement is emerging as the security guarantee to renew common interests of natural partners. Australia’s commitment cannot be understated. We have everything to play for in preserving enough of Pax Americana to maintain our concept of Australia within the rules-based order on which our economy and way of living depend.

The real risk to our strategic objectives is Australian demographics. We can’t expect a sovereign workforce enabling our strategic partnership commitments to emerge from within. The demographic trends demand an alternative. Australians are ageing and not attracted to defence careers. A declining percentage of Australia’s population will pass the fitness and security vetting for jobs in the Defence Department and other security agencies even if inclined to join. The 2023 review of Australia’s migration system reports that it is not fit for purpose and is enabling an expanding underclass of temporary workers. Divided loyalties are an increasingly vocal trend in Australia’s pluralist society. It is for others to quantify the AUKUS human resources bill, but put simply Australian demographics don’t support Defence’s workforce objectives.

In February, eminent naval strategist James Goldrick noted that if Australia is to embark on the AUKUS nuclear-powered submarine program, the bill in people must be understood and met from the outset. The commitment to AUKUS is not diminishing, and time is pressing to be innovative in finding the human resources to achieve AUKUS. The AUKUS SSN pathway statements set ambitious job-creation targets but lack detail on innovative ways to find the resources.

A new naval entity to achieve the maritime-security guarantee under AUKUS is a concept worth testing. Exploiting ambiguity in Australia’s sovereignty narrative is a compelling challenge to take us beyond unsustainable nationalism. AUKUS provides an opportunity for a fresh approach to collective security among nations with an interest in sustaining an open global trading system governed by markets and the rule of law. Partner nations would contribute resources, but the AUKUS SSN fleet could be controlled as a federated entity.

The strategic advantage offered by submarines is ambiguity. That advantage is multiplied by the size of the networked submarine fleet, the compelling opportunity of AUKUS. So, if the strategic guarantee offered by an AUKUS fleet is greater than the sum of the parts of the participant nations, would the partners be better served by a fleet of SSNs flying AUKUS flags?

An AUKUS fleet would potentially, and by necessity, illustrate efficiency and effectiveness outcomes over existing national navies. Operationalised by a franchise model with central command and control, an AUKUS fleet could be characterised by the collective objective of unrestricted oceans and the interoperability of fleet operations and sustainment. Its genesis should include specific consideration of the workforce and crewing requirements of each submarine.

The conceptual goal would be crews comprising a mix of partner nations. The nationality of the submarine command shouldn’t be fixed to specific submarines. Indeed, it may be an operational advantage for this aspect to be ambiguous to an adversary. Home basing of the submarines and their crews will require nuance and new ideas, but with the right incentives both can be inherently mobile.

The raise, train and sustain aspects of an AUKUS fleet workforce will demand careful attention, but it will provide opportunities over existing national stovepipes. Flexibility will be key and AUKUS partners will need to find ways to expand the partnership from a crewing perspective. Specifically, pathways for like-minded nations (Canada, New Zealand and others) to join the partnership must be envisaged.

The model for training must be driven by efficiency and managed to avoid duplication. Centres of excellence will be required to master the standards and develop curriculum for an AUKUS fleet. Training delivery could be franchised and centrally controlled in a similar but separate arrangement to operational command and control. The sustainment aspects of an AUKUS fleet workforce can only be speculated, but there should be no doubt that it will test the resolve of the partners.

AUKUS may provide Australia’s future security guarantee as part of a reinterpreted international communion of interests, but developing the resources to enable it will require a rebalancing of sovereignty ambitions to prioritise the common interests of the AUKUS partners.

The wars raging in Europe and the Middle East remind us that conflicts erupt suddenly. It’s a point that some AUKUS critics have seized on to say Australia and its partners are not making sufficient progress to be battle-ready in the Indo-Pacific.

Certainly, we need urgent investment to increase our military preparedness. But this fact doesn’t reflect badly on AUKUS.

AUKUS is about a longer game. Sceptics who are already declaring the partnership a failure because it won’t deliver nuclear-propelled submarines for decades, and therefore will produce no military or strategic returns in a useful timeframe, are missing the point.

This was always about much more than filling a single or immediate capability gap. It is about giving us the best chance to deter aggression, now and in the future, and therefore prevent a war with the Indo-Pacific’s major strategic challenge, China.

Deterrence relies on having strong capabilities, but also on credibility. Intent matters and it was missing, for example, in Europe before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. AUKUS, even in its nascent stage, is the clearest signal that the three countries are resolved, and working together, to meet the China challenge.

With the right political and industrial support, and the necessary resources, AUKUS shows Beijing that we are collaborating on security-related technologies such as quantum, artificial intelligence and autonomous systems that will be decisive in the strategic competition defining our period and the decades ahead.

By turbocharging the advantages inherent in our market-based innovation culture, we will be best positioned to offset China’s massive technology push supported by military spending.

Even by the historical standards of geostrategic competition, this current intense period is marked by an unprecedented convergence of economics and security. Implemented effectively, AUKUS demonstrates the intent that underpins the capability and credibility necessary to deter war and deny Beijing any benefit from starting one.

Projecting this intent, Defence Minister Richard Marles met his US counterpart, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, in Washington last week following Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s visit with President Joe Biden the week before, injecting further impetus and political commitment in the AUKUS process.

Demonstrating bipartisanship in the long-term national interest, Labor not only backed AUKUS but doubled down on the arrangement—with senior government figures including Marles supporting it at the party’s feisty national convention—as a generational, whole-of-nation endeavour.

AUKUS addresses the reality that a collective approach to security with trusted partners is a strategic advantage. No country, not even the US, is strong enough alone to confidently deter and compete with a power of China’s size.

Pentagon officials say that, for now, US submarine technology is better than Chinese technology, but the sheer numerical advantages of China’s maritime fleet demonstrate the old military saying that ‘quantity has a quality of its own’. This captures the strategy that Australia, the US and partners must follow and explains why we need AUKUS: comparative advantage is gained by working with and strengthening friends.

Leveraging each other’s aptitudes by working together puts us in a firmer position to tackle a strategic competitor in China. Fusing its civil and military sectors, China’s strategy openly seeks to monopolise key economic, defence and technological capabilities, including through a combination of intellectual property theft, coercion, interference, and unfair subsidies and investment arrangements. It is these practices and Beijing’s malign intent that motivated AUKUS.

The belated realisation that the world cannot be walled off into neat spheres and regions, due to the global nature of technology and economic supply chains (including in space and cyberspace), makes it significant that the AUKUS partners span the geography of the planet.

And while our open, market-based economic approaches confer advantages in spurring innovation and generating industrial energy, national resilience is strengthened when friendly nations work together and governments concurrently collaborate with industry and incentivise defence and technology industries to cooperate across nations.

There are of course legitimate challenges with AUKUS. They include real workforce and skill shortages, funding and infrastructure gaps, and regulatory restrictions. Each of these poses risks.

The answer, however, is not fatalism but government and industry leadership and a cultural shift to understand that our respective interests lie in collective power. As much as sceptics focus on political distractions in Washington, Albanese and Biden ensured AUKUS was a top priority at their recent meeting, noting progress across both pillars including the first graduation of Australian military personnel from the US Navy’s Nuclear Power School, the first Australian port visit by an American nuclear attack submarine, and the first demonstration of AUKUS artificial intelligence and autonomous capabilities. This was a clear signal of intent and resolve ahead of Albanese’s trip to China.

At the same time, a hearing of the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces showed the strength of bipartisan support for AUKUS, with members—including Republican Mike Gallagher and Democrat Joe Courtney—backing supplemental funding and export control reform.

Support doesn’t equal a blank cheque and reasonable questions are being asked in Washington—not just in Congress but in other parts of government—yet these aim to ensure that AUKUS is a success.

The expectation that the necessary domestic political reforms for such a tectonic shift as AUKUS would come easily were always unrealistic. Meanwhile, many of the criticisms about technology-transfer restrictions, difficulties building submarines in Adelaide or the potential for a war this decade are issues that would apply more acutely without a bold initiative like AUKUS.

This is about having a coherent, long-term strategy, at which many authoritarians excel because they are untroubled by the demands of democracy (from elections to protecting the rights of citizens). As a senior figure instrumental to AUKUS remarked at a Washington dialogue ASPI hosted with the Center for a New American Security earlier this year, this partnership is about ensuring the three allies are so intimate that we ‘finish each other’s sentences’ on matters of strategy and security.

There is still much work to be done to deter China and preserve our own sovereignty, but AUKUS is already making a difference, establishing a tight-knit, collective approach to defence policy and the key capabilities that will shape the rest of the century—not just today or tomorrow.

Australian Labor Party debates on defence policy are often full of passion and vigour, especially those involving regional security, nuclear issues and the alliance with the United States. A combination of all three has made the AUKUS agreement a lightning rod for debate in the party—so much so that in the lead-up to last month’s ALP National Convention it was reported that the political wrangling in the party represented an ‘internal Labor rebellion over AUKUS’.

Smouldering opposition from elements of the party’s left to the plan to acquire nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs) generated headlines for weeks. Reports tallied opposition from local party branches and high-powered former Labor figures, including former prime minister Paul Keating and former senators Bob Carr, Doug Cameron and Margaret Reynolds. As the conference reached its conclusion, we were told the ‘Labor debate over AUKUS hangs in the balance’.

This was simply not the case.

The local branch opposition highlighted in the lead-up to the conference represented a small fraction of the party. Reports of 40 local branches across the country passing motions questioning or opposing the AUKUS pact amounted to less than half of the 101 branches in Western Australia alone.

At the conference, the party’s parliamentary national security team led by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese had its way. Defence Minister Richard Marles and Defence Industry Minister Pat Conroy sealed deals with union and factional bosses to include a statement on AUKUS and SSNs in the party’s national platform. The Electrical Trades Union, the Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union and the Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union all backed down after negotiations over investment and policy pledges on housing and jobs in manufacturing and clean energy transition. Despite legitimate concerns about AUKUS, it appears opposition was artfully traded for bargaining on domestic party-political issues.

As far as revolts go, it was more about colour and movement than action. There was no manning of the policy barricades and no metaphorical storming of the stage.

There was no rebellion.

In the end, support for AUKUS was resoundingly endorsed by delegates.

Indeed, the conference represents the most important revolution in Labor’s approach to defence policy in 60 years.

Nuclear propulsion for Australia’s next generation of submarines now represents a central element of Labor’s national platform for regional peace and stability. This is no small outcome. Ideological opposition to nuclear issues runs very deep in the party. Hard-nosed national-security pragmatism triumphed over idealism. As The Australian’s Paul Kelly wrote: ‘The Labor Party has turned on the hinge of history.’

Nuclear-powered submarines are now a core Labor value and a critical part of the party’s platform to support both deterrence and self-reliance. This expands Labor’s approach to defence into a new era that embraces national resilience and industrial revitalisation. Resilience is a core component of Labor’s new doctrine of ‘national defence’ delivered by the defence strategic review led by former Labor foreign and defence minister Stephen Smith and former chief of the Australian Defence Force Angus Houston. As Albanese noted at the conference, ‘maximising [national] resilience is an opportunity to maximise Australian jobs’.

The AUKUS agreement and the acquisition of US Virginia-class SSNs in advance of a fleet of Australian-built SSNs constitute the most visible and tangible evidence of Australia’s long-term commitment to the common defence of the Indo-Pacific and the alliance with the US.

This makes support for AUKUS the most significant move in the party since the 1963 Labor Federal Conference.

The 1963 conference dealt with the establishment of the North-West Cape naval communications installation, which it accepted on the basis that the facility was under joint control and available to Australian forces. It noted that ‘in the event of the USA being at war … Australian territory and Australian facilities must not be used in any way that would involve Australia without the prior knowledge and consent of the Australian government’. Australia’s involvement in a war, it made clear, was a sovereign decision.

These conditions were applied to the agreements over the joint installations at Pine Gap and Nurrungar later in the decade. ‘Prior knowledge and consent’ was cemented by the Hawke government in the 1980s, and Australian participation was agreed in the management and operations of the facilities at all levels. They effectively became part of the Australian order of battle.

Back in the 1960s, the federal conference, not the parliamentary party, determined this outcome. Numerous subsequent reforms have changed the Labor Party from a federal party of state machines to a national party. It includes federal and state parliamentary leadership and some federal politicians, with the other delegates proportionately elected based on state population sizes.

The national conference reflects those changes and provides greater authority to those effectively elected by the people. It reinforces a new era of the US alliance, with sovereign control and self-reliance at its core. This is why its embrace of AUKUS as a core Labor value is so significant.

Labor’s new AUKUS platform represents the views of the broader Australian community. The 2023 Lowy Institute poll noted that two-thirds of Australians (67%) support the decision to acquire SSNs under AUKUS.

The conference debate fundamentally reflects a wider debate within the nation. At the core of this stands our understanding of the changing regional order and Australia’s role and approach to maintaining peace and prosperity.

Labor’s stance reflects broader community concerns about the Indo-Pacific strategic order, increasing foreign interference, espionage and cyberattacks on Australia. It’s an acknowledgement of the risks posed to Australian interests and values in our region including by the massive and opaque increase in China’s military capabilities, its use of coercive tactics across the region, its extensive nuclear weapons modernisation, its support for North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, and it’s ‘no limits’ friendship with Russia.

AUKUS also recognises that this is not a Labor problem, or a national problem, or even a problem for the US alliance to resolve. It’s an Indo-Pacific regional problem. It’s about the type of multipolar order emerging in our region. As Foreign Minister Penny Wong noted at the National Press Club in April, it’s about how ‘we contribute to the regional balance of power that keeps the peace by shaping the region we want … to avert conflict and maintain peace. That is what the countries of the region want too.’

Labor’s 2023 platform represents a genuine change in its approach to defence and national security. As with the issues addressed in 1963, this platform is driven by the changing risks our nation faces, and 2023 goes down in history alongside the revolutionary changes at the 1963 Labor conference. No one wants to have to spend more on defence or to adopt new capabilities to increase our national security. But Labor’s adoption of the AUKUS pact is reflective, as the prime minister noted in his conference address, of ‘analysing the world as it is rather than as we would want it to be’.

In September 2021, the Chinese Communist Party attempted to use the establishment of the AUKUS pact and Australia’s plan for nuclear-powered submarines to undermine the strong ties between Pacific island countries and the three AUKUS partners. The CCP’s messaging was spread across a broad spectrum of information channels, including Chinese state media, articles and statements by CCP officials in local and social media, and official party-state Facebook groups.

An ASPI study found that the campaign failed to shift Pacific islands’ sentiment against Australia and its partners in the short term, but it can take some time for information operations to make an impact. In some Pacific countries, particularly Solomon Islands, online sentiment towards foreign partners and local governments in response to AUKUS has since shifted.

In March this year, further details about the AUKUS partnership were announced, including the timelines for additional visits of US and UK submarines to Australia and the pathway for Australia’s acquisition of nuclear-powered submarines starting in the 2030s. The CCP’s response to these announcements was more subdued than in 2021, although Chinese diplomats and state media continued to question the agreement’s intent and presented AUKUS as a threat to stability in the Pacific.

Regularly investigating how the CCP capitalises on Pacific events to spread propaganda and disinformation helps detect changes in its efforts, approaches and effectiveness. Measuring online sentiment also provides insights into how different narratives are perceived by Pacific island populations.

For this new study examining the CCP’s influence in the Pacific islands information environment, we tracked online discussion of AUKUS across the Pacific for four weeks beginning on 14 March, the day the submarine announcements were made. We looked for any mention of AUKUS or nuclear submarines in Pacific online articles, press statements and opinion pieces by governments and officials, and Facebook posts on official embassy pages and by individuals in more than 50 of the Pacific’s largest public Facebook groups. The methodology is explained in greater detail in our earlier report.

During the study period, and as in 2021, the CCP pushed clear narratives and disinformation, including false claims that Australia’s submarine acquisition would breach the Treaty of Rarotonga (also referred to as the South Pacific Nuclear-Free-Zone Treaty) and threaten regional security and prosperity. The CCP sought to undermine the AUKUS countries’ Pacific partnerships by exaggerating the nuclear-safety implications of the AUKUS agreement and claiming that it would trigger a nuclear arms race in the Pacific.

Capitalising on other regional events, the CCP entwined AUKUS with Pacific concerns about Japan’s plans to release nuclear wastewater from Fukushima into the Pacific Ocean. The CCP has similarly sought to undermine Japan’s government on the wastewater issue through a covert social media campaign.

In the month following the 14 March announcement, Chinese state media continued to criticise AUKUS. The number of published articles mentioning AUKUS and the Pacific increased from 9 in 2021 to 16 in 2023. In both studies, the Facebook page of China’s embassy in Solomon Islands was the only Chinese embassy page in the region that displayed any content on the AUKUS announcement.

The lone statement from a CCP official in Pacific media, published online by Solomon Star News, was a response from a spokesperson from the Chinese embassy in Honiara addressing remarks by Japanese and US officials. In this response, the CCP attempted to shift the focus away from concerns about China’s recently signed security agreement with Solomon Islands by raising nuclear-safety concerns with Japan and the US—a technique known as ‘whataboutism’.

As in 2021, Chinese state media had limited penetration and engagement in the Pacific islands online information environment. Only one article was shared to a Pacific public Facebook page, titled ‘Front Line Papua New Guinea’. It did not generate engagement or interactions, such as likes, comments or shares. However, state media was still published in print format across the region. China has content-sharing arrangements with various Pacific media outlets, which serve as an additional avenue for its messaging efforts.

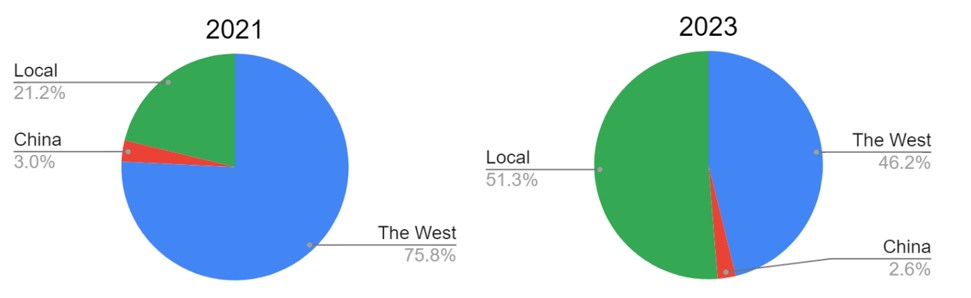

We found 39 articles about AUKUS, including opinion pieces and press releases, published by the 30 Pacific media outlets sampled. This was a slight increase on the 33 AUKUS-related articles we found in 2021. The following charts show the origins of AUKUS-related media content in the Pacific during the 2021 and 2023 study periods. There was a significant increase in the amount of locally produced content in March 2023 compared with September 2021 and less reliance on publishing Western articles.

As in 2021, online reaction from the Pacific population was limited. We found only 157 direct comments across all sampled data, 67 of which were relevant for sentiment analysis. Social media data analysis tool Crowdtangle consistently ranked AUKUS content as ‘underperforming’ in generating engagement compared with other posts on the same Facebook pages.

In both studies, the people of Solomon Islands and Samoa were the most engaged on AUKUS issues online. The number of reactions in Solomon Islands commentary was disproportionately high given its share of overall media coverage.

Solomon Islands was also where we found the most dramatic change in online responses and sentiment. In September 2021, most of the comments in Solomon Islands’ groups focused primarily on China, either welcoming its statements of support or criticising its presence in the region and defending AUKUS as a necessary capability boost for Australia. In March 2023, commentary was significantly more critical of Australia and the US, using language similar to that used by CCP diplomats, such as describing the West as having a ‘Cold War mentality’. Concerns over the Treaty of Rarotonga were raised frequently in negative comments in Solomon Islands and Samoa.

Compared to the 2021 study—which was conducted before key events in Solomon Islands, such as the November 2021 Honiara riots and the March 2022 security agreement with China—we found a significant increase in negative comments towards the Solomon Islands government. They were mainly focused on the government’s lack of transparency in signing the security agreement with China, indicating that the CCP’s whataboutism approach hadn’t distracted all of the population from ongoing concerns. A comment on a Chinese embassy post also accused the account of deleting further commentary that reflected poorly on the embassy, potentially biasing the sample to favour China.

While the two studies consider particularly small datasets, they still provide useful comparisons over time. Our findings suggest that the AUKUS partners should prioritise providing further clarification on the agreement to the people of Solomon Islands and Samoa in order to debunk rumours and counter disinformation. And, given that most online engagement occurs through local media pages, Australia, the US and the UK should seek to engage directly with Pacific journalists to provide additional information and support Pacific-based reporting on this issue.

AUSMIN 2023 will occur against the backdrop of the largest ever iteration of Exercise Talisman Sabre in Australia’s north. Talisman Sabre, a bilateral exercise between the US and Australia, has long been a symbol of interoperability between the two nations. However, in recent years, it has assumed a larger role, demonstrating how the alliance partners can work with other regional and extra-regional nations. In the most uncertain global strategic circumstances we have faced since World War II, it reveals the vital roles hard-power capability plays in diplomatic statecraft, in regional stability and as the underpinning of deterrence.

All these facets—from statecraft and stability to diplomacy and deterrence—have been enhanced by the addition of 11 partner nations in the 2023 iteration of the exercise. Talisman Sabre featured prominently in the December 2022 joint AUSMIN statement, which announced the intent to include a number of Pacific nations in the exercise, including Papua New Guinea, Fiji and Tonga.

The symbolism is clear, and significant, but it will yet again be necessary for AUSMIN, and the joint communiqué, to signal substantial progress on the defence side as well as on the foreign policy objectives of cooperation. This, of course, doesn’t mean that the talks in themselves are not highly beneficial for the defence relationship between the two staunch allies. Yet with one authoritarian regime waging war in Europe and another carrying out a coercive form of grey-zone aggression in the Indo-Pacific, AUSMIN needs to be crystal clear that continued and increased investment in defence both bilaterally and with partners is not about military proliferation or the creation of instability but is necessary for regional stability—or as President Ronald Reagan said, a strategy of ‘peace through strength’.

Understandably, most of the discussion on threats faced by the Australia–US alliance and our partners will occur in the classified, closed-door sessions,. But the 2022 communiqué set a high bar in terms of bringing the public along the, at times, tension-filled journey of international security. Among other things, it provided a clear focus on force posture initiatives, including bomber taskforce rotations, sustainment and maintenance.

Given the significance of the AUKUS optimal submarine pathway decision earlier this year, the announceables at this AUSMIN are unlikely to be groundbreaking—and are more likely to be reserved for the visit of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to Washington later this year. That in itself isn’t a problem; the constant desire for big new announcements should be avoided. Instead, from a public-facing standpoint, the principals will likely focus on practical initiatives to consolidate the 2022 AUSMIN themes of force posture initiatives and logistics. Details on key force posture initiatives including US bomber rotations and infrastructure commitments to northern Australian bare bases such as Tindal are much needed.

As a key element of deterrence, it is important to demonstrate that these discussions will bear fruit for operational outcomes. The urgency of the strategic competition between the US and China—importantly, in which Australia, along with others, is a participant—set out in the defence strategic review must be underpinned by practical progress on the initiatives outlined in AUSMIN 2022.

This is also relevant to Australia’s flailing guided weapons and explosive ordnance enterprise (GWEO), an initiative with strategic importance for both the US and Australia, and on which AUSMIN 2023 should deliver some much-needed progress on US support.

From a messaging standpoint, this weekend’s meeting will likely provide a forum for Defence Minister Richard Marles and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin to again condemn a number of the unsafe practices of the People’s Liberation Army in the South China Sea. However, the language around this is likely to attempt to strike a fine balance as both countries seek to court more stable ties with the People’s Republic of China. Still, it remains AUSMIN’s duty to hold aggressive actions in breach of international rules to account. A softening of language around international rules at a time when Moscow is flagrantly breaching them would only incentivise Beijing to continue its malicious behavior.

In this context, and following Albanese’s trip to Vilnius, there will be further joint messaging on Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine. A key here will be to not limit such messaging to Europe, but to continue the cooperation seen at NATO which clearly outlined that security in the Euro-Atlantic is connected to the Indo-Pacific.

It is on the Ukraine question that there’s potential for more closed-door discussion. The US is likely to pressure Australia to consider doing more to support Ukraine; and, on the question of doing more, it would be interesting to see if the US raises a behind-closed-doors discussion on Australian defence funding, both for Ukraine and in general. That’s a delicate subject, of course, but it is certain not to have gone unnoticed by our major allies that the rhetoric of the recent defence strategic review has not been supported by additional funding in what would likely be deemed a strategically relevant timeframe.

Following the major announcements of the past few years, there will hopefully be behind-closed-doors discussions to ensure that these announcements translate into practical outcomes. Concrete effort between the two countries on GWEO and the wider barriers of the US International Traffic in Arms Regulations and export controls are needed. The US will likely need to provide some assurances on the recent rhetoric in Congress about support for the transfer of Virginia-class nuclear-powered submarines to Australia in the 2030s, shoring up AUKUS arrangements in a bipartisan fashion.

All in all, the timing of the last AUSMIN just seven months ago and Albanese’s expected visit to Washington raise the potential that much of the concrete discussion will be kept behind closed doors. But as with international security, strategic balance is key, and so it will still be vital for defence to feature prominently—in private and in public—in this year’s meeting. The Talisman Sabre backdrop sets the perfect scene to send the message that AUSMIN 2023 has a heavy defence and security focus.

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria