A few millennia after recording the basic tenets of hard-edged power politics and creating the historian’s craft, Thucydides has popped up in the South China Sea.

A few millennia after recording the basic tenets of hard-edged power politics and creating the historian’s craft, Thucydides has popped up in the South China Sea.

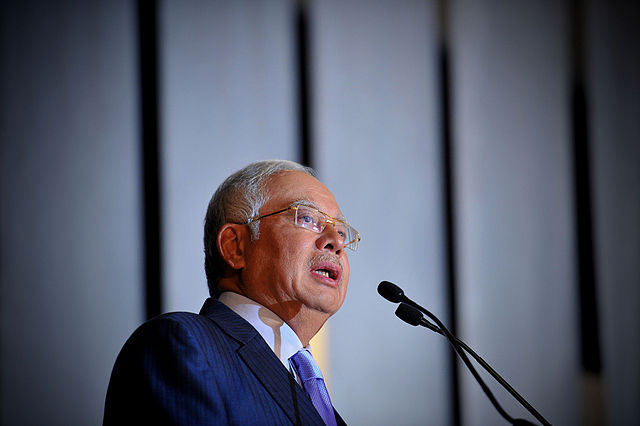

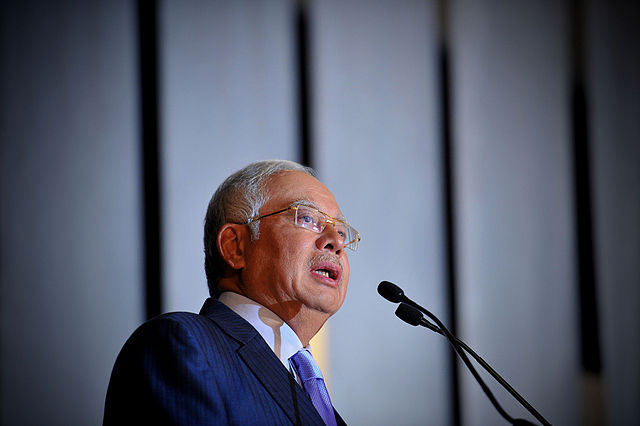

Malaysia’s Prime Minister has dipped into the historian, philosopher and general’s works to quote his most famous sentence on how raw power works in relations between states. Here’s how Najib Razak invoked Athens and Sparta, launching the 28th Asia-Pacific Roundtable in Kuala Lumpur:

Imagine a world where institutions, rules and norms are ignored, forgotten or cast aside; in which countries with large economies and strong armies dominate, forcing the rest to accept the outcome. This would be a world where, in the words of the Greek historian Thucydides, ‘The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must’.

The theme running through my previous posts, from the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, was that trust has been lost and the region’s now desperate for a bit of law and order. The Roundtable in KL offers more of the same.

Najib’s speech kept returning to that theme of power politics usurping Asia’s order. The Prime Minister’s final line was a plea for Asia to prosper and progress by ‘observing the rules and norms and institutions we have developed and built together’.

The distance from Singapore to KL, however, is more than a 45 minute flight. At Shangri-La, Japan, the US and Australia were all vocal in labelling China the great disruptor challenging the status quo and international norms.

Not so in Malaysia’s keynote address. In Najib’s speech, China wasn’t mentioned, although the South China Sea was one of the major problems discussed. And Najib didn’t actually deliver his speech in person. The Malaysian PM has been in China to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations. So mark this as a Malaysian discussion of China delivered indirectly and by inference; the old ASEAN way in action.

One irony that struck me is how Malaysian demonology has shifted. In many years of listening to speeches by Dr Mahathir, I always knew who the PM was talking about when he railed against a brutal and unprincipled superpower. Not only did the US impose its raw power on everyone else, according to Dr M, the Americans also set the unequal rules for the global economy. So the US was guilty on two counts—in the way it used its military power and the way it policed economic norms. In KL demonology now, China is the power that does what it wants and challenges ‘the norms and institutions’ Asia has built. Just don’t state that case too loudly or too directly.

Malaysia steps up next year to take the ASEAN chair and KL will inherit the job of holding ASEAN together while responding to the mounting pressure from China. KL thinks that it has an important asset in doing that job because Malaysia prides itself on having a special bilateral relationship with China; that was the motif of Najib’s China tour.

One bit of evidence KL offers for this special relationship is the fact that China has never sought to muscle-up against Malaysia over their conflicting claims in the South China Sea. It’s an interesting perspective because of what it assumes about the overall coherence of what China has been doing—monster the Philippines, challenge Vietnam but leave Malaysia alone. That presumes a China that knows exactly what it’s doing and who should be on the receiving end—the calculated imposition of power to change the system. Thucydides would understand.

Graeme Dobell is the ASPI journalist fellow. He is reporting from the 28th Asia-Pacific Roundtable in Kuala Lumpur. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The topic I was given at the recent Submarine Institute of Australia conference was ‘The Strategic Environment in the period 2020-2050’. That gave me a chance to reprise in part a lecture I gave in 2010 at the Australian National University, when I was asked to prognosticate about the Asian security environment in 2050.

The topic I was given at the recent Submarine Institute of Australia conference was ‘The Strategic Environment in the period 2020-2050’. That gave me a chance to reprise in part a lecture I gave in 2010 at the Australian National University, when I was asked to prognosticate about the Asian security environment in 2050.