Building the Indo-Pacific defence industry base

Indo-Pacific alliances and partnerships are a key advantage of the United States in competing with China.

Now the United States seeks an economic version of that strategic advantage with a Statement of Principles for Indo-Pacific Defence Industrial Base Collaboration.

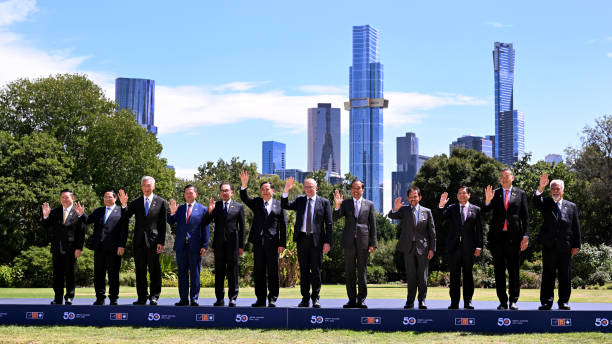

It released the statement at the Shangri-La dialogue in Singapore last week. Australia and other allies immediately endorsed it.

Australian Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles said the point of such new groupings was to foster ‘a constellation of states’ that acted as a force multiplier for collective security and delivered network effects.

New formations would serve different functions, Marles said, ‘some normative, some about capability, some about security, others about industry integration. Building more resilient supply chains is a key priority for Australia, which is why I’m endorsing at this dialogue the Statement of Principles to strengthen the region’s defence industrial bases.’

The principles for defence industrial resilience in the Indo-Pacific call for collaboration to:

· expand industrial-base capability, capacity and workforce;

· increase supply chain resilience;

· promote defence innovation;

· improve information sharing;

· encourage standardization; and

· reduce barriers to cooperation.

The work must be ‘consistent with free and fair market competition and protection of intellectual property’ and will involve governments, industry, capital providers, academia and other forms of partnership.

Nothing more specific was said about the proposed defence-industry cooperation. No one said how deep it would be, what sort of military systems it would cover nor even which countries would be included, though they would be ‘like-minded participants’.

This effort is driven by the same factors that motivated the Biden administration’s 2022 Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity, not least the China challenge and Asia asking Washington what it has to offer.

The defence dimension is a response to the pain and the pleas of allies and partners over many years about the difficulty of buying some kinds of defence equipment from the United States or partnering with it in military manufacturing.

As the chairman of the US House of Representatives foreign affairs committee, Michael McCaul, said last year, America’s ‘approach to defence and military technology exports is in dire need of reform’.

American officials say the AUKUS partnership with Australia and Britain has been an important learning experience, showing Washington how US laws stand in the way of equipment partnerships. The United States is offering what it has done for Australia to other Indo-Pacific countries in a more general and gentle version.

As well as noting the AUKUS agreement, the United States points to co-development with Japan of a glide-phase interceptor to counter hypersonic threats; partnership with Australia and Japan on an integrated air-and-missile defence architecture; and work with India on co-producing fighter engines and armoured vehicles.

US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin said that before joining the Biden administration he had had personal experience of the problems of partnership. ‘Several years ago, we set out with a notion to gain approval for India to build jet engines for fighter aircraft in India. I served on a board of a company that makes jet engines for fighter aircraft and I know how difficult this was going to be. And we were hopeful but very sceptical that we could get this across the finish line. We did it. That’s happening.’

Austin said the industrial commitment to the Indo-Pacific had enough momentum to continue, no matter who won the US presidential election in November.

In AUKUS, Australia is near the top of the US partnership hierarchy. Other close allies face a steep climb to get there. How difficult was shown at the Shangri-La dialogue by a question to Austin from Chung Min Lee, a professor at Korea’s Advanced Institute for Science and Technology:

The US has always said that the Republic of Korea is a lynchpin of Asian policy and security in the region. And yet, unlike AUKUS, the US has been quite lukewarm to South Korea’s desire to have nuclear-powered submarines. So, my question to you, sir, is if the South Korean government officially asks Washington for its support in building nuclear-powered submarines for the ROK Navy would you support such an initiative?

A version of AUKUS for South Korea would be ‘very, very difficult for us’, the US defence secretary replied. The initiative with Australia and Britain was a generational investment, he said. ‘This is no small endeavour. It is very, very difficult to go through each piece of this. And so, we’ve just started down this path with Australia. Highly doubtful that we could take on another initiative of this type any time in the near future.’

The nuclear crown jewels of AUKUS mean it is a rare deal—so rare that Canberra had formerly known it needn’t bother to ask Washington for help in building nuclear submarines. It had known the answer would be a firm ‘No.’

China changed that, just as it has caused the United States to launch this new effort to build the Indo-Pacific defence industrial base. At a time when US politics is protectionist—turning inward with trade barriers and tariffs—the industrial principles show a United States still able to look outward to what its allies and partners need.