Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Last week, the leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) met on the island of Flores, Indonesia, for the annual ASEAN summit and related meetings. Once again, the post-coup conflict in Myanmar was at the top of the agenda.

To highlight ongoing difficulties for ASEAN policymakers, at the start of the week staff from the Indonesian and Singaporean embassies in Yangon and personnel from an ASEAN humanitarian assistance centre travelling in Myanmar’s Shan State were shot at by unknown assailants.

By the end of the week reports were appearing of a massacre by the military of 19 civilians, including four children, in a village in the central Bago Region. This followed an airstrike with a ‘thermobaric’ munition on 11 April that caused over 160 deaths, including children, in the village of Pa Zi Gyi in northern Sagaing Region, which Human Rights Watch called an ‘apparent war crime’.

In response to the conflict in Myanmar, the statement at the end of the Summit again called for an ‘immediate cessation of violence in Myanmar’ and reiterated support for the failed ‘Five-Point Consensus’, even though the Summit’s Chair, Indonesian President Joko Widodo, admitted there had been ‘no significant progress’ on the plan. Such a mild diplomatic response to the unfolding crisis is a consequence of the need for consensus among ASEAN members and represent the lowest common denominator of concern about Myanmar.

Still, some members of ASEAN have been forceful in their criticism of the Myanmar military. The fact is that the Myanmar chair has remained empty at most ASEAN meetings since the Summit of 2021, to which the military were politely disinvited. Other ASEAN members have been somewhat more forgiving, but no more successful at building consensus, with Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen, who chaired ASEAN in 2022, failing in his attempts to rein in the Myanmar military.

It has also become apparent that Thailand, as well as India, have been engaged in Track 1.5 diplomacy—hosting meetings with the military and representatives of neighbouring countries, with the anti-coup National Unity Government (NUG) a noticeable absentee.

The Thai government, led by 2014 coup-leader Prayuth Chan-ocha, has been less interested in engaging the NUG than the governments of Indonesia and Malaysia, and more concerned with placating the Myanmar military and coup leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. Prayuth’s intimate understanding of the dilemmas facing another coup-maker-in-chief is hardly surprising.

This is where the Thai election of last Sunday could hold the key to a more substantial shift in ASEAN policy. After a phenomenal showing at the polls, the liberal Move Forward party looks likely to be the largest party in the new parliament. If constitutional impediments designed by the Thai military junta can be overcome, the charismatic young leader of the party, Pita Limjaroenrat, may well be the next prime minister.

Move Forward has been the most outspoken of the major parties in rejecting any compromise with the military and its proxy parties in Thailand, and Pita is unlikely to be amenable to the military junta in neighbouring Myanmar. His election success also highlights the widening chasm between established, and often authoritarian, Southeast Asian powerbrokers and the aspirations of a rising generation of more progressive and internationally oriented young people.

In Thailand, that generation made their feelings known in large-scale anti-military and anti-monarchy protests in recent years. Now they are flexing their muscles at the ballot box.

And now, if Pita, an eloquent business figure with a strong understanding of the global system, takes the top job then he will likely want to shake up the conservative priorities of ASEAN too.

Of course, in Bangkok there will be the usual heavily contested coalition politics to navigate, as well as the ever-present threat of a future military intervention. Nevertheless, a Move Forward-led coalition would want to quickly leave its stamp on foreign policy, including the management of the long border with Myanmar.

Could such a Thailand shift the weight of ASEAN concerns from state stability to these intractable humanitarian crises, and even towards the democratic will of the Myanmar people? Bangkok’s foreign policy thinkers understand perhaps better than anyone that there are major risks, for all, in the further entrenchment of Myanmar military rule. Young people in Myanmar will also look to the Thai election as an example of what patient but relentless activism can ultimately achieve.

For now, there is still much negotiation required after the poor electoral showing of Thailand’s military-aligned parties, and good reasons to remain watchful of what could prove a further period of violence and brinksmanship. But if Move Forward can use its ballot box success as a path towards power, then all of ASEAN will take notice.

Thailand has much at stake in Myanmar’s future, and, if its own military strongmen now relinquish control, the weekend’s election could spark a change in the region’s approach to its most pressing strategic and humanitarian crisis.

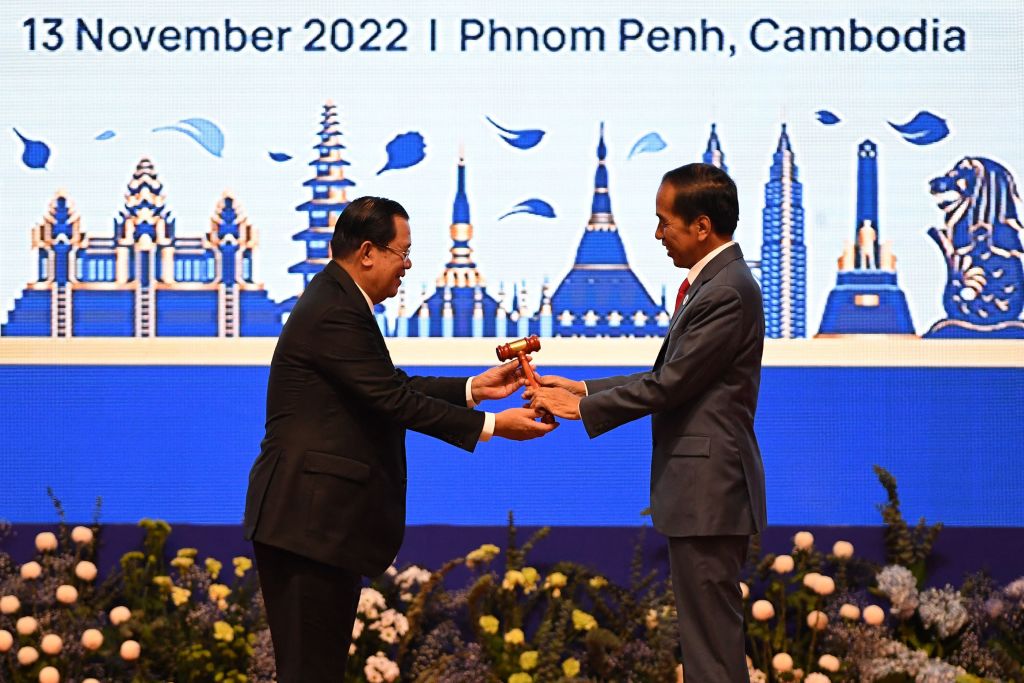

Last month, just days before hosting the G20 summit in Bali, Indonesia was officially named as chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations for 2023.

In chairing ASEAN, Indonesia will play a pivotal role in setting the agenda for the hundreds of meetings ASEAN regularly hosts each year for its 10 member states, as well as the 27 other countries that are regularly engaged as dialogue partners and as members of ASEAN’s ‘plus’ mechanisms, like the ASEAN Regional Forum. President Joko Widodo, who is normally uninterested in foreign affairs, will also have the opportunity to (once again) play the role of international spokesman after globetrotting as the face of the G20 in 2022.

So, what’s likely to be on the agenda in 2023?

At the very top is post-Covid-19 economic recovery and economic cooperation. Widodo announced the theme of Indonesia’s chairmanship as ‘ASEAN matters: epicentrum of growth’. The theme is, in many ways, a response to two sources of insecurity for ASEAN that relate to its relevance in the 2020s: the association’s diminishing voice in an era of great-power competition, and the ability of the association to offer economic benefits to its 684 million people.

In response to the latter, officials have long been working to deepen economic integration to bolster regional economic growth, encourage intramural trade flows and strengthen ASEAN’s power as a bloc. In the past, attempts have been undermined by a lack of enthusiasm to break down tariff and non-tariff barriers. However, the Covid-19 pandemic has given impetus for states to address mutual concerns regarding supply-chain resilience and digital trade. While Southeast Asia has done relatively well in recovering from the pandemic, disruptions in global value chains have hit its manufacturing centres hard, forcing governments to assess the long-term security of supply chains.

Indonesia will likely focus on ensuring commitments to meeting the ASEAN 2025 vision, particularly provisions that relate to digital connectivity and trade. The Covid-19 pandemic has increased the pace of digital transformation in the region, and thus accelerated cyber dependency.

What may be the centrepiece of the Indonesian chairmanship, however, is the ascension of Timor-Leste as a full member of ASEAN. After more than a decade of lobbying, Timor-Leste achieved a major diplomatic win at the 2022 ASEAN summit when it was able to get other member states to agree in principle to accept its application for membership. Indonesia has been the strongest advocate for Timor-Leste’s membership of ASEAN and Jakarta will want to see its ascension as soon as possible.

However, Indonesia’s success as ASEAN chair will likely be assessed based on how it manages two big challenges. The first is the ongoing turmoil in Myanmar, which has not only dominated discussions within ASEAN but also been a topic of international concern. ASEAN’s attempts to address the situation through a five-point consensus has largely failed; the junta continues to commit acts of violence. With Myanmar scheduled to have (likely rigged and unfair) general elections in 2023, there will be high expectations that Indonesia will apply more pressure on the junta.

The second major challenge is dealing with the strategic implications of Sino-American rivalry on Southeast Asia. Widodo has said that ASEAN’s key objective under Indonesia’s chairmanship will be ‘not to be a proxy to any powers’. That statement follows a trend among Southeast Asian leaders of expressing serious concern and anxiety about the effects of great-power competition on ASEAN’s strategic autonomy.

While the US and China seem to have had a temporary moment of rapprochement following the meeting between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping in Bali, great-power rivalry still has the potential to compound regional economic and security concerns. For example, the attempted technological decoupling of the two powers may disrupt Southeast Asia’s information and communications technology ecosystem, which depends on support, resources and technical knowledge from Chinese, Japanese, European and American tech firms.

There’s also the need to face other potential volatilities, like the South China Sea disputes—the central security flashpoint in Southeast Asia. Indonesia has already sought to coordinate regional efforts to redress this balance of power in the region. However, given the internal contradictions within ASEAN’s members and their varying levels of distrust of China, a common policy approach, or consensus, could be hard to find, and that could be beneficial to China.

Southeast Asia’s relationship with China is a complex one with competing geostrategic and geoeconomic priorities. The region’s priority remains economic development as it faces massive infrastructure gaps, and China is funding key infrastructure projects across many sectors, including transport (high-speed rail and bridges) and energy (power plants, often coal powered). China has substantial economic influence and heft in the region.

Yet China is also strategically challenging the sovereignty of the countries in the region through its behaviour in the South China Sea. Indonesia is aware that a unified ASEAN bloc, and indeed a cohesive Southeast Asia, would be the best deterrent against an assertive rising China, and that will be its single most important challenge—to bring cohesion to the region, economically as well as strategically. Its success will be measured by how it bridges the strategic and economic dissonance in 2023.

Given Widodo’s stated dual aim of not falling into the great-power competition and focusing on the region’s economic recovery, there are signs that Indonesia’s chairmanship will likely try to focus on regional connectivity as a means to achieve both aims, but that may be a challenging task. The push for Timor-Leste’s inclusion in ASEAN is likely to be driven by the strategic vision that no country in Southeast Asia should fall under any one power’s influence. Given the potential for Timor-Leste to fall under China’s economic influence, its inclusion in ASEAN could ensure that it diversifies its economy and integrates with the region, lessening its dependence on China.

Expectations are often (a bit too) high for the Indonesian chair. As the region’s largest country, Indonesia is often seen as the primus inter pares of ASEAN’s member states, each of which commands veto power over the association’s decision-making. Nonetheless, Indonesian diplomats will likely reflect on past symbolic successes. In 2003, the Indonesian chairmanship passed the Bali Concord II, which initiated plans to construct the ASEAN Community. In 2011, Indonesia laid the foundations for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership agreement—the world’s largest free-trade area—which came into effect on 1 January 2022.

With this being Jokowi’s (and, most likely, Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi’s) last ASEAN summit, we can expect some attempts at legacy making. But whether it’s about economic integration or Timor-Leste’s ascension, the Indonesian chairmanship will likely be faced with serious challenges beyond its control. Whereas the benchmark for success for Indonesia’s chairmanship of the G20 this year was its ability to run a meeting that was as ‘normal’ as possible in the face of major global challenges, the benchmark for success for an Indonesian chairmanship of ASEAN is much, much higher.

The headline news for Australia out of last week’s G20 summit in Bali was the meeting between Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Chinese leader Xi Jinping. The prospect of repairing relations between Australia and China is an overdue development and in the interests of both countries.

But while China tends to dominate the foreign policy debate in Australia and elsewhere, there’s more to our engagement with Asia than getting on with Beijing. The Albanese–Xi meeting appropriately took place in the midst of three of the biggest leaders’ summits on the international calendar—which, as it happens, were all held in Southeast Asia.

If Australia’s relationship with China is to have a sustainable recovery, it will be built in large part on demonstrating a strong diplomatic presence in ASEAN, which straddles the region of greatest strategic importance to us. ASEAN also has a record of convening ‘inclusive’ meetings that bring all sides, not just the like-minded, into one room.

Sure, the Albanese government has promised a continued commitment to the Quad—and to AUKUS—but talk of Australian and ASEAN futures being ‘tied together’, and the recent appointment of a high-profile special envoy for Southeast Asia, suggest some fresh strategic thinking. We cannot assume, however, that moving closer to ASEAN will be uncomplicated.

Australia has lost ground with Southeast Asia. At a recent seminar commemorating our leadership in bringing a form of peace to Cambodia 30 years ago, discussants doubted whether Australia could play such a regional role today. The strategic context has changed; our great ally, America no longer possesses unrivalled power and China is becoming recognised across Southeast Asia as the regional leader.

A second challenge we face is that Australia–ASEAN relativities have changed dramatically. Australia has continued to grow, but much of Southeast Asia has developed more quickly. For Australia, ASEAN is second only to China as a trading partner. But we are less important to Southeast Asian countries, accounting for well under 3% of their trade.

Our economy is also now smaller than Southeast Asia’s. Three decades ago, Australia’s GDP was larger than the combined GDP of the ASEAN countries. Today, their GDP is far greater than ours—more than double by some measures—and also larger than the GDP of India, a country we often call a potential great power. ASEAN has also become China’s number one trade partner.

Economic capacity plays into defence capability. Australia easily outspent ASEAN three decades ago, but today ASEAN spending on defence is some 60% greater. With benchmarking against US forces, and recent combat experience, Australia still has a capability edge in key areas, but our lead is now less conspicuous.

A third challenge in strengthening ASEAN relations is that we now face far more competition for Southeast Asian attention. China isn’t the only nation to have risen meteorically as an economic partner. South Korea, once a country of little economic significance to Southeast Asia, is now well over twice as important as Australia as an ASEAN trading partner—and a serious investor. Australia—unlike Japan, the Netherlands and Switzerland, as well as Korea—isn’t listed among the main investors in ASEAN.

The findings of the 2022 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute survey of the region’s opinion leaders are sobering. Australia does well enough as a place for university education—equal to Japan and well ahead of Korea—and as a provider of Covid-19 support. But we now rank low against other ASEAN partner states in terms of economic and security influence—as well as in providing leadership in ‘maintaining the rules-based order’ and ‘championing global free trade’.

Three or four decades ago, apart from the Cambodia initiative, Australia was spearheading the Cairns Group of Fair Trading Nations and was central in the creation of APEC.

A fourth challenge relates to contrasts in political culture. In the decades following the Pacific War, Australia was the local representative of the dominant global ideology, liberal democracy. Today—with the relative decline of US influence—we must take distinctive Asian perspectives far more seriously.

In foreign policy, Southeast Asians tend to be uncomfortable with military alliances. Rather than automatically balancing against a rising power, they prefer working through regional organisations that are ‘inclusive’—seeking to ‘socialise’ rising states, such as China. They are wary, too, about interference in the internal affairs of another country. China’s ideology is seen as China’s business—and Vietnam’s ideology hasn’t prevented it from becoming a leading ASEAN state.

Sometimes to Australia’s frustration, the unity of ASEAN is viewed as more important than decisive action—for instance, in pursuing political or even human rights issues. Although Southeast Asians are political gradualists, in economic development they favour dynamism—and increasingly lack respect for Australia in this area.

Noting Australia’s regional relations, an influential Singapore commentator warns that, with American decline, Australia may become isolated—a type of ‘Cuba in Asia’. The answer is not to become ‘Southeast Asian’, but it is unwise to express disdain for Southeast Asian preferences, as some of our leading commentators have done.

A fifth challenge to an ASEAN priority is that the wider Australian community connects only weakly with these countries. Amazingly, there’s little stress on the languages and societies of Australia’s neighbours in our university and school system. The Lowy poll on ‘Australian attitudes’ suggests a lack not only of knowledge, but also of interest and warmth. True, we take an increasingly positive view of Japan, but the one distinct theme in our international outlook is dedication to the US alliance. Half the Australian population hasn’t even caught up with Indonesia’s ‘remarkable transition to democracy’—a development which PM John Howard highlighted time and again.

Over two centuries, Australians have engaged in the great project of building a liberal democracy on this continent. With some important exceptions, we have been less creative in our international relations. Southeast Asians and others suspect that Australia has not yet come to terms with its geographic setting. To do so may require some reimagining of Australia’s identity, as well as foreign policy.

The recent executions of four high-profile democracy activists in Myanmar—the first to take place in the country in more than three decades—plainly demonstrate the enduring brutality of its military regime. Since ousting the civilian government in a coup d’état in February of last year, Myanmar’s military regime, known as the State Administrative Council (SAC), has murdered at least 2,220 civilians, forcibly displaced more than 900,000, and led the economy to the brink of collapse, forcing millions into poverty.

The sheer scale of violence and devastation brought about by the junta forced even the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, a regional organisation well known for its adherence to the principle of ‘non-interference’, to lay out a comprehensive roadmap towards a resolution of the ongoing crisis. This ASEAN-backed plan, known as the ‘five-point consensus’, laid out a set of actions agreed among all parties to reduce hostilities. Most critically, it called for an ‘immediate cessation’ to the violence across the country and for ‘constructive dialogue among all parties concerned’.

More than a year later, however, the junta and its leader, Min Aung Hlaing, have shown little willingness to implement any of the agreement’s provisions. Instead, the regime has ramped up its crackdown on dissent and repeatedly violated the agreement’s terms by refusing to engage with the political opposition. Recent events that continue to demonstrate the junta’s unwillingness to abide by the terms of the agreement have amplified the document’s myriad shortcomings, and made it increasingly difficult for ASEAN members to ignore that it has become an abject failure.

Speaking at the ASEAN foreign ministers’ meeting in Phnom Penh in August, Prime Minister Hun Sen of Cambodia—this year’s rotating chair of ASEAN—said that if more political prisoners were to be executed by the SAC, ASEAN would be ‘forced’ to rethink its role in relation to the agreement. Similarly, Malaysia’s foreign minister, Saifuddin Abdullah, an outspoken critic of the troubled peace process, repeatedly stressed the need for ASEAN to ‘morally support’ and engage with Myanmar’s parallel National Unity Government (NUG). In a Facebook post written in response to the executions, Saifuddin stated in not-so-subtle terms that the junta was ‘making a mockery’ of the agreement.

While it remains unlikely that ASEAN will attempt to completely overhaul the agreement due to the SAC’s non-compliance, the ministers’ joint communiqué indicates that the structure and framework of the deal could soon be reconfigured.

Capitalising on ASEAN’s frustration with the junta’s truculence, the NUG recently opened offices in several Western countries to apply new diplomatic pressure. In Australia, the NUG held an opening ceremony for its first representative office in Canberra in early August. The Australian Greens announced at the ceremony that the party would begin to recognise the NUG as the official government of Myanmar, and encouraged other political parties to do the same.

The opening of the NUG office marks a watershed moment for Australia and presents an opportunity for the government to strengthen its approach. Although Australia has effectively downgraded its relations with Myanmar since the coup, it still hasn’t imposed any sanctions on military leaders, and has simultaneously taken steps that confuse its overall stance on the crisis.

Andrea Faulkner, the former Australian ambassador to Myanmar, for instance, met with Min Aung Hlaing in April. According to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Faulkner used her meeting to urge the junta to ‘cease violence, release arbitrary detainees, engage in dialogue and ensure unimpeded access for humanitarian assistance’. One of the detainees whose release she specifically called for is an Australian citizen, Sean Turnell. Although DFAT considers Faulkner’s visit to have been undertaken in good faith, activists in Myanmar viewed it as conferring unnecessary legitimacy on the SAC. And it was one of at least eight meetings or phone calls Australian officials have had with representatives of the junta since the coup. Whatever the purpose, they demonstrate Australia’s willingness to engage directly with the SAC.

While Australia’s position towards Myanmar is evolving under the Labor government of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, the country’s approach is becoming increasingly untenable—especially as Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi prepares to take the reins as ASEAN’s special envoy to Myanmar in Indonesia’s capacity as next year’s ASEAN chair.

One of the most vocal critics of the five-point consensus and the Myanmar regime, Marsudi led the charge at last year’s ASEAN summit to exclude the SAC at the political level from all ASEAN meetings, saying that the country shouldn’t be represented until it had restored democracy ‘through an inclusive process’. At the foreign ministers’ meeting last month, Marsudi said that Indonesia had not seen any commitment or ‘goodwill’ from the SAC to implement the agreement. A substantial reconfiguration under her leadership may soon become a reality.

With a shift in ASEAN’s approach towards Myanmar likely on the horizon, Australia should take the opportunity to expand its engagement with the NUG and work with ASEAN to reinvigorate a stronger regional response to the crisis. The Albanese government has identified deeper engagement with ASEAN as a priority of its foreign policy, and it should capitalise on Australia’s comprehensive strategic partnership with ASEAN to address the most pressing issue facing the region.

Engaging with the NUG in an informal, but public, capacity will allow Australian officials to develop a better understanding of the crisis, and provide an opportunity to listen to the needs of Myanmar’s people, such as for humanitarian assistance, access to education, and assistance in good governance that will help the NUG to build capacity and make it more effective at organising itself and delivering for the Myanmar people.

While this engagement should ultimately extend beyond the NUG representative office in Canberra, the office can act as a conduit for formal talks between Australian officials and NUG representatives in Myanmar.

With a more aggressive ASEAN chair taking the helm next year, it should behove Australia to work more closely with Indonesia and other ASEAN partners to forge a consistent dialogue between ASEAN and the NUG.

The UK government’s Integrated review of security, defence, development and foreign policy presents the Indo-Pacific as a region of increasing geopolitical and economic importance over the next decade and suggests that competition will play out in ‘regional militarisation, maritime tensions and contest over the rules and norms linked to trade and technology’.

The contested and congested oceans and connectivity links that make up the Indo-Pacific form an epicentre of great-power competition in which Southeast Asia is central.

Closer engagement with ASEAN states is therefore an essential part of a strategy that seeks to position the UK as a global actor in the era of strategic competition. But Britain is not alone, and an increasing number of other European countries are reasserting their positions in the region too.

Following the British government’s announcement of its Indo-Pacific tilt, in 2021 the UK became the newest ASEAN dialogue partner (Australia was the first, in 1974) and deployed a carrier strike group to tour the Indo-Pacific. Operation Fortis was the UK’s largest operational naval deployment to Asia since the 1997 handover of Hong Kong.

In the wake of the AUKUS announcement and in light of the UK’s broader maritime ambitions, how can the UK work with Australia to contribute to maritime security in the Indo-Pacific? What can they jointly bring to this crowded space? And how can ‘external powers’ engage with ASEAN states in areas of common interest while circumventing sensitivities and avoiding raising tensions?

In a new ASPI report, released today, UK, Australia and ASEAN cooperation for safer seas: a case for elevating the cyber–maritime security nexus, we identify cybersecurity and technology capacity-building as priorities for UK–Australia–ASEAN cooperation in maritime security. This is a value-adding area that draws on the strengths of the UK and Australia to foster partnerships with non-military actors and addresses civilian-related aspects of maritime security.

The list of cyber incidents affecting maritime security is slowly but steadily growing and includes the malfunctioning of critical control systems, the exfiltration of sensitive data, the manipulation of systems to allow trafficking and smuggling to occur unnoticed, commercial and military espionage, spoofing of navigation systems, and manipulation of identification transmissions. While digitisation and automation of processes have been a priority for the maritime industry, cybersecurity has been lagging other comparable critical sectors of the global economy.

A first steppingstone for cybersecurity capability is access to incident-response resources. Some initiatives have been undertaken, including by Singapore’s port authority and maritime-focused cybersecurity companies, but altogether these efforts are just a drop in the ocean, given the magnitude of Southeast Asia’s maritime activity and the lack of an industry- and region-wide approach to and apprehension of the risk.

Risks aside, digital and emerging technologies are presenting marine industries with huge potential. Access to ‘maritime big data’, in combination with applications based on artificial intelligence and machine learning, will help to inform decisions on the most efficient routing; precise and reliable forecasting of scheduled arrivals; docking, off-boarding, load forwarding and reloading; and insurance of risks related to maintenance and accidents.

The Verumar project in the Philippines identified nine groups of technologies that are disrupting conventional fishing and other marine economic activities. Collecting and analysing meteorological, oceanographic and hydrographic data is helping efforts to support responsible fishing and combat illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing; track of maritime pollution; and monitor maritime economic resources and biodiversity.

Strengthening capabilities for maritime domain awareness through the adoption of digital technologies serves joint UK–Australia–ASEAN interests and their respective industries. The UK and Australia would be well placed to take responsibility for standard-setting in the development and deployment of these emerging technologies so that they reflect shared norms and the needs of the Indo-Pacific maritime community.

Maritime supply-chain resilience is emerging as a significant economic and security concern. The incident in 2021, in which MS Ever Given obstructed traffic in the Suez Canal, immediately reverberated through global supply chains and demonstrated the dependence of the world economy on accurate forecasting. Delays and disruptions in the shipping of critical rare-earth minerals prompted Australian mining company Lynas Rare Earths to charter its own vessel and secure a continuity of supply to customers through a processing facility in Malaysia.

Overall, the industry is expected to need to meet demands for faster and more accurate and predictive shipping. As Southeast Asia continues to ride the wave of e-commerce, major manufacturers will require logistics partners that are more flexible and agile. An ‘Uberisation’ of maritime transport is already taking shape that may soon involve a greater number of shippers operating with more small and medium-sized transporters.

Southeast Asia is not a chokepoint only for maritime trade but also for internet connectivity. With a high concentration of fibre-optic cables landing in and through the region, Southeast Asia is gradually developing into a hub for hyperscale data providers in the region’s digital economy.

Marine-based infrastructure such as communications cables and relay stations on the ocean floor is often overlooked, but is responsible for transporting 95% of the world’s data. While deliberate disruptions to undersea cables may occur, especially when exact locations are known, they are more likely to be damaged as a result of natural disasters or accidental collisions. The Indonesian government recognised that vulnerability when it tasked the navy’s Hydrography and Oceanography Centre to map and potentially rearrange its underwater geophysical landscape of cable and pipes to mitigate potential threats.

By exploring the cybersecurity and emerging technology dimensions of maritime security, the UK and Australia enter largely uncharted territory. Both countries, however, possess a demonstrated track record of maritime, cyber and tech expertise, experience and resources to partner with ASEAN countries in building further regional capacity in technology-enabled maritime security.

Managing the advent of new technologies in Southeast Asia’s maritime operations—military, civil and commercial—and ensuring the confidentiality, integrity and availability of systems and networks will increasingly underpin the safety and security of the maritime domain, including the legal aspects of maritime borders.

The Myanmar crisis and its fallout have become one of the greatest tests for ASEAN in its history. Doubts about the group’s relevance, credibility and utility have arisen over the past decade, largely because of its ineffective reaction to many regional challenges. But its unedifying response to the Myanmar crisis is amplifying those doubts and exposing the shortcomings of ‘the ASEAN way’. Ultimately, this is not in Australia’s interests and Canberra should be doing more to advance and protect them.

While the military coup in Myanmar wasn’t the first for an ASEAN state, never before has ASEAN faced a non-compliant member that not only blatantly disregards its decisions but cites the ASEAN charter against it. This was a consequence of the group’s decision to disinvite the junta’s leader, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, from last month’s ASEAN summits because of his regime’s lack of progress and cooperation in stabilising the country and ceasing violence. ASEAN offered ‘non-political representation’ instead, but Min Aung Hlaing condemned the move as a violation of ASEAN’s consensus principle and Myanmar was not represented at the virtual summits.

As a result, ASEAN has become a group of nine, instead of 10, functional members—for the first time in its history—and the question that follows is: what’s next for ASEAN?

While Myanmar’s effective informal suspension from ASEAN ensured the association escaped the condemnation that would have come with permitting the junta to be represented, it hasn’t stopped criticism of ASEAN’s perceived ineffectiveness and ineptitude. These problems stem mainly from ASEAN’s inadequate crisis-management mechanisms and its charter’s lack of enforcement tools. Grounded in principles of non-interference and consensus-only decision-making, ‘the ASEAN way’ relies on diplomacy, dialogue and goodwill. It loses its way when these facets are missing, as the junta’s recalcitrance has shown.

The Myanmar crisis has also exposed divisions within the group. These are not new. They arise naturally from the member states’ differing national interests and ideological bases, which recent events—and the need for ASEAN to respond to them—have brought into stark relief. Developments in Myanmar have highlighted not just the diverse interests of ASEAN nations vis-à-vis Myanmar but also the different views among them on such values as liberal democracy and human rights.

A new ASPI report, released today, recounts and assesses the security situation in Myanmar, ASEAN’s collective response and the individual roles of key ASEAN member states in the mediation process. It focuses on the crisis’s effect on ASEAN’s political and security circumstances and highlights Indonesia’s leadership, and its limitations, in the process. As arguably Southeast Asia’s most democratic polity and the state most responsible for injecting notions of democracy into ASEAN’s charter, Indonesia has tried to engineer an acceptable resolution through ASEAN. But its own adherence to ASEAN’s foundational principles of non-interference and consensus have constrained its efforts.

The report also examines the ASEAN charter as a legal and policy instrument, highlighting its inherent complications and their impact on ASEAN’s capacity to ensure members uphold the rule of law and practise the principles codified in the document.

The report concludes that the most likely outcomes of the current situation in Myanmar are an entrenched Tatmadaw regime or worsening violence and the risk of all-out civil war, and considers the implications for the wider region, especially Australia. The more the generals’ brutality destabilises Myanmar and its neighbourhood, the more those developments conflict with Australia’s (and ASEAN members’) interest in a stable ASEAN focused on common economic, social and political goals, and whose ‘unity in diversity’ isn’t facing an acute risk of fracturing. As Australia’s Foreign Minister Marise Payne has said, ‘The political stability of ASEAN member states is essential to achieving our vision for a secure, peaceful, prosperous and open Indo-Pacific region with ASEAN at its centre.’

The coup has also disrupted a part of Australia’s own plans to play a greater role in the region. One of the ways that Canberra intended to do so was by means of a package of assistance to Southeast Asia worth more than $500 million that was announced at the East Asia Summit in November 2020. Along with pledges to supply Covid-19 vaccine doses to Southeast Asia, this represents Australia’s largest funding commitment to the region since the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

If effecting change in Myanmar is proving to be beyond ASEAN’s capacity, it is certainly well beyond Australia’s. If the bleaker scenarios for Myanmar over the coming decade eventuate, Canberra will have no choice but to engage with the regime to protect and advance Australia’s security interests, including on countering the illicit drug trade.

Above all, as a regional middle power, Australia retains an interest in seeing the Indo-Pacific’s future determined as much as possible through diplomacy rather than the simple exercise of power. Only a functional and responsive ASEAN can warrant its much-vaunted centrality. Since Australia retains an interest in an ASEAN fit for the role it has assumed as the region’s central actor, it is incumbent on Canberra to do all it can to help make this happen, especially in an era of great-power politics.

Fortuitously, recent events afford new opportunities for doing so. At the recent summits, Australia’s relations with ASEAN were elevated to a comprehensive strategic partnership. If this status is to mean anything beyond rhetoric, the Australian government should use it to undertake more intensive and sustained diplomacy with key ASEAN partners towards helping them change ASEAN’s direction.

Specifically, Australia should actively encourage and support ASEAN to initiate reforms, including in its decision-making mechanisms. The government should aim to reassure interlocutors that Australia values the role an effective ASEAN can play in mediating great-power tensions while encouraging it to heed internal calls for change so that it can perform that role more compellingly. For many ASEAN partners, such forthrightness in urging the association to make its own adjustments towards hard-edged reality so that it can perform the role that ideally it should do would likely ring truer than formulaic blandishments about ASEAN’s centrality.

As this year’s ASEAN chair, Brunei Darussalam finds itself operating in an increasingly precarious and unpredictable region.

While Southeast Asia begins to heal from the Covid-19 pandemic that brought the region to a standstill for most of last year, Brunei has the formidable task of guiding it towards a post-recovery era. With the theme of ‘We Care. We Prepare. We Prosper’, Brunei has largely concentrated its chairmanship on strengthening the regional healthcare infrastructure in a post-pandemic landscape.

However, early this year, the ASEAN chair was forced to focus on an entirely unexpected challenge—the military coup and accompanying violence that erupted in Myanmar. Brunei has since become engaged in a series of regional consultations, quiet diplomacy and concerns about major-power intervention amid fears of domestic spillovers and recurring waves of the pandemic.

It now confronts an entirely different set of challenges to those it anticipated.

Last month’s ASEAN Leaders’ Meeting at the organisation’s secretariat in Jakarta became a point of tension. In a bid to de-escalate the crisis, ASEAN invited coup leader Min Aung Hlaing to the meeting but that drew a mixed reaction from civil society groups and Myanmar citizens concerned that the invitation recognised him as his country’s legitimate representative.

The summit produced a joint statement and a five-point consensus through which ASEAN leaders hoped to address the spiralling violence in Myanmar.

In Jakarta, Min Aung Hlaing displayed an apparently conciliatory attitude. He did not reject calls to end the violence and he met with the United Nations Special Envoy for Myanmar Christine Schraner Burgener.

But in Myanmar the bloodshed continues.

ASEAN’s approach has been based on its political desire for cooperation rather than enforcement, so the fact that the five-point consensus offered neither a timeline nor a plan to apply pressure on the coup leaders is not surprising. While Brunei and other ASEAN leaders are still working on nominating a Myanmar envoy, critics believe the summit offered Myanmar’s armed forces, the Tatmadaw, an opportunity to seek legitimacy externally while continuing to repress the people.

The Myanmar crisis is a test that Brunei, and everyone else in the region, were not prepared for. With its ‘We Care. We Prepare. We Prosper’ theme, Brunei sought to protect the ASEAN community by prioritising treatment to ensure swift recovery, expediting vaccine distribution and protecting online services.

This led to the Strategic and Holistic Initiative to Link ASEAN Responses to Emergencies and Disasters (ASEAN SHIELD) and the establishment of a taskforce to preserve digital safety and ensure accurate information flows. A second pillar of this strategy sets out to ensure a stable post-pandemic regional future by managing changing major-power relations and security threats, including spillovers from the instability in Myanmar.

Here, Brunei finds itself upholding priorities it has long championed such as a rules-based architecture and constructive relations between major powers as demonstrated by ASEAN’s first invitation to attend the G7 ministerial meeting with partners such as the United States.

Given changing security dynamics, there’s also a broader push to maintain ASEAN’s relevance, especially with the release of documents such as the ‘ASEAN outlook on the Indo-Pacific’.

In the third pillar, seeking prosperity, Brunei advocates for more opportunities through a people-centred approach that focuses on 10 economic priorities including recovery, digitalisation and sustainability.

This year, the region is likely to see Brunei building on the recently signed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership to support more non-tariff measures on trade, revive industry sectors, optimise e-commerce and promote sustainable growth.

By beginning the year with a business advisory council meeting and a retreat for senior economic officials, Brunei clearly seeks to vigorously support a broader multilateral trading and security system. Indeed, since taking the chairmanship, Brunei has engaged with long-standing partners such as the United Kingdom by welcoming Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab to Brunei and supporting the UK’s admission as an ASEAN dialogue partner.

Brunei’s three priorities are clearly complementary and, carried out consistently, would help provide a stable post-pandemic order amid regional challenges.

But with the spotlight on the ongoing instability in Myanmar, the test for Brunei’s chairmanship has largely been framed as its ability to lead an effective regional response to the atrocities there. Crafting a peaceful resolution in Myanmar would not only mark the legacy of Brunei’s 2021 chairmanship but would also form a milestone for ASEAN.

It may be a tall order for this gargantuan task to fall upon the shoulders of Brunei, but this country offers the potential for compassionate leadership that the Myanmar crisis desperately needs.

For decades, the economic development of ASEAN member states was hindered by persistent shortages in high-quality infrastructure. The issue wasn’t a lack of desire but a lack of access to equity and investment. Securing foreign direct investment for infrastructure between the 1997 Asian economic crisis and the 2008 global financial crisis was particularly challenging for ASEAN states.

China’s economic miracle has solved that problem. Chinese direct investment was already flowing into the region before President Xi Jinping announced the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013. Nonetheless, the introduction of the BRI was a watershed moment in ASEAN infrastructure development.

By 2015, with infrastructure projects in train and foreign direct investment flowing, ASEAN leaders were able to commit to not just thinking about regional economics but implementing measures to cohesively achieve practical integration.

At the 2015 Kuala Lumpur summit, they committed to continuing regional integration and adopted Vision 2025. To achieve the statement’s goals, ASEAN members agreed on three supporting blueprints: the ASEAN Political and Security Community Blueprint, the ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint and the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community Blueprint.

The plan for realising the ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint 2025 seeks to attain a highly integrated and cohesive economy; a competitive, innovative and dynamic ASEAN; enhanced connectivity and sectoral cooperation; a resilient, inclusive, people-oriented and people-centred ASEAN; and a global ASEAN.

From 2016, this development would be augmented by additional investments from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Since 2016, ASEAN member states have, for the most part, been able to generate the foreign investment capital needed to accelerate economic growth in Asia.

Upgrading ground transport links—the railways and road networks that make up ASEAN’s main economic corridors—had been an ongoing priority. Success here has been due in no small part to the Chinese government’s financing and BRI projects. Until Covid-19 hit, Chinese investments in regional connectivity—roads, bridges, train lines and ports—were creating all-new levels of regional connectivity.

So, what’s the problem then? Well, there are three: the quality and sustainability of those investments, the debts associated with them, and the potential supply-chain vulnerabilities that they have created.

Infrastructure development across ASEAN, but especially in the Mekong region, has occurred at a breakneck pace. The rapid acquisition of foreign direct investment, while welcomed, has resulted in general concerns over the quality and sustainability of infrastructure projects. In some cases, foreign government investors have been indemnified by sovereign immunity, so there will be little in the way of accountability if quality problems result in realised risks.

Of more significant concern are the long-term implications of the conditions associated with many of these investments. In many cases, the terms of the loans are opaque. Arguably, for some of the countries involved, especially Myanmar, Laos and Cambodia, the repayment of loans, no matter how generous the terms were, will be difficult if not impossible. These kinds of arrangements ought to raise concerns in ASEAN and beyond over the potential use of debt-based diplomacy, especially by the Chinese government.

The broader national security challenges relates to critical national infrastructure, supply-chain vulnerability and national resilience. Developers of infrastructure gain a great deal of information about the countries in which they operate. Through foreign direct investment, the governments of countries such as China can acquire in-depth knowledge of critical national infrastructure and its inherent vulnerabilities. The region’s desperate demand for infrastructure investment has resulted in a reduced policy focus on security.

The opaque relationship between Chinese engineering and construction companies and the Chinese state is alone cause for concern. Chinese state-owned companies have access to eye-wateringly large amounts of valuable economic and security information. Such knowledge provides a strategic advantage during every phase of a potential conflict. A hostile government can leverage significant value from it, using both soft and hard power. And this kind of knowledge is critical to those who might want to disrupt national regional and global supply chains. With that advantage, a hostile country, or even one with competing interests, can profoundly undermine a competitor’s national resilience.

The Covid-19 crisis has drastically reduced foreign direct investment. It has also created an opportunity for the ASEAN member states to critically reassess their infrastructure requirements and mitigate the risks of foreign investment.

ASEAN has an opportunity to leverage its economic integration efforts to respond to its member states’ infrastructure risks. A regional body or network could monitor and certify aspects of future infrastructure development to address quality, sustainability and security aspects.

While foreign direct investment has dried up, global markets are adjusting to the pandemic’s economic impacts. Interest rates are at historic lows, and expectations for returns on investment have changed. The financial crisis resulting from the pandemic is still unfolding, but, like all crises, it too will pass. And when it does, infrastructure investment in the ASEAN region will once more accelerate, which is why now is as good a time as any to synchronise economic growth and security.

US–China, US–China—the commentary goes on and on. Who will be dominant? Must rising powers always go to war with established powers? Can the US assemble an Indo-Pacific alliance to balance China? Might the US agree to share primacy?

These are urgent questions—but some recent Asian perspectives (including from a Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific survey) suggest a growing impatience with what a Japanese analyst calls these ‘bilateral dynamics’. There is talk of the need to reinvigorate multilateralism—and one line of thought suggests that the often-denigrated ASEAN could lead a multilateralism effort that transcends the US–China contest.

The performance of both China and the US has disappointed. Covid-19 started in China, and Beijing has been seen as bullying several neighbours. Regarding the US, the ‘appearance of incompetence in managing the pandemic’ is one factor in the judgement (of a senior Philippines observer) that the ‘post–Second World War order built around US hegemony … is ending’.

The interesting point, however, comes from Japan. Analyst Tsutomu Kikuchi reminds us that Asia is ‘more than the US and China’—and that numerous countries and institutions in ‘the rest of Asia’ have ‘substantial political, economic, military and sociocultural power’. The continued agency of ‘small and medium-sized countries’, in fact, is often stressed by regional analysts—and Kikuchi suggests their ‘prime goal’ ought to be ‘to sustain and further enhance the rules-based order’, because such states tend to be protected by ‘strong binding rules’.

Looking beyond the US and China, who could lead such endeavours? Interestingly, Kikuchi notes the continuing capacities of ASEAN. It and other multilateral institutions, of course, have received plenty of criticism. From the United Nations downwards, their handling of the Covid-19 crisis has not impressed. An experienced Cambodian observer sees ‘individual initiatives at the national level’ but no ‘concrete actions’ from ASEAN or ASEAN+3. Even the EU has struggled to act in concert—despite the alarming rise in numbers of infection and mortality among its members.

This said, the current crisis has highlighted not sidelined multilateralism. As the Cambodian observes, the virus ‘crosses national borders, and a regional response makes a lot more sense’. A Chinese commentator adds that the actual ‘methodology necessary in responding to Covid-19 demands a level of international cooperation more comprehensive than we have achieved before’.

Mixed with criticism of ASEAN, Kikuchi is not alone in expressing a degree of optimism. Some analysts even believe the pandemic might inspire an ambitious ‘reset’.

A review of ASEAN’s potential does seem warranted—especially as there are no other obvious candidates likely to build a consensual regional order. Various ASEAN-led institutions do, after all, encompass the entire Asia–Pacific region. Also, the organisation’s track record throughout the challenging post–Cold War period is better than its many critics suggest. Recall that the East Asia Summit, which includes every serious player in the region, was an ASEAN initiative, as were the wide-membership security forums—the ASEAN Regional Forum and the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting Plus. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which seeks to promote open trade and investment, was launched in 2012, again by ASEAN—and incorporates every country in Southeast and Northeast Asia, as well as Australia and New Zealand.

The point is often made that ASEAN is no match for China. This would be hard to deny. In the South China Sea, the Southeast Asians are merely small countries invoking the rule of law to buttress their sovereignty. It is also true, however, that the ASEAN–China relationship contains positive elements—including investment inflow, and the fact that ASEAN became China’s largest trading partner in 2020. Also, as former Malaysian prime minister Mahathir Mohamad often pointed out, Southeast Asians are used to negotiating with a powerful China—and they believe that China, unlike the US, is invested in their region for the long haul.

There is pride in the careful way Southeast Asia embraced communist China, commencing in the 1970s—and in the part ASEAN played in rehabilitating China internationally following the Tiananmen Square massacres of 1989. The initiation of the Asian-centric ASEAN+3 process in 1997, after decades of US presence and support of the economies of Southeast Asia, highlights ASEAN’s agency in engaging a multiplicity of players judged to be able to benefit the region. As leading Thai analyst Kavi Chongkittavorn has pointed out, the ‘Plus Three’ element was also an ASEAN contribution to bridge-building between the large, mutually hostile states of Northeast Asia (China, Japan and South Korea).

Initiatives from ASEAN, therefore, would not be interpreted automatically in the framework of US–China rivalry. Even a greater ASEAN engagement with Japan and South Korea would not need to be viewed as Cold War alliance-building. Over the past year there have been various reports of improved relations between China and its Northeast Asian neighbours—and Kavi insists that although ‘historical grievances and border disputes will not disappear overnight’ the Covid-19 crisis has provided an opportunity to benefit from ‘shared anxieties and worries’.

Such a shift in Northeast Asian sentiments could be a game-changer across the Asian region. At the least, more relaxed interstate relations in Northeast Asia—fostered, in part, by ASEAN—would provide a more favourable setting for the further development of ASEAN-led rules-based regional building.

The fact that the Southeast Asian states (with the partial exception of Indonesia) are small in Asian terms is not a deterrent to ASEAN agency. It helps ASEAN to appear non-threatening; also, over many centuries, Southeast Asians have become accustomed to functioning in state-to-state hierarchies, developing strategies to handle those above them. Even a state growing in strength was not necessarily seen as a threat—was not automatically resisted or balanced against. Such a state might rather be embraced or socialised—in a manner beneficial to both sides.

Historically, this was the approach to China. With such a heritage of valuing agency while operating in a hierarchy, ASEAN may be better qualified than most in ‘the rest of Asia’ to promote a multilateral rule-structure—a structure that will not immediately be viewed as antagonistic to China, but may help to restrain China or any other major power capable of disrupting this region of the world. What is needed now from the ASEAN states is the creative leadership they have on occasion demonstrated in the past.

Thailand is already almost halfway through its ASEAN chairmanship in what has been a rather low-profile period considering political developments. In the lead-up to Thailand’s elections on 24 March, the country’s political energy was directed inwards. The results from the poll are scheduled to be announced on 9 May. It’s also an important year for other ASEAN member states. Indonesia exercised its democracy with general elections a couple of weeks ago, while the Philippines is gearing up for mid-terms.

Globally, it hasn’t been an easy-going year so far either: there are heightened uncertainties, rising protectionism and security tensions in the Korean peninsula and South China Sea, all of which could pose problems to Southeast Asian nations. In the past, Thailand has stood up to some big challenges, including during the 2008 global financial crisis, when it chaired ASEAN too. What footprint it will leave this time around?

So far, security hasn’t figured highly on this year’s host’s agenda. Take the South China Sea case. Last year, under Singapore’s chairmanship and despite heightened tension in the group (although not without internal incongruity), ASEAN put a collaborative face to the game of China’s extensive claims and hailed milestone progress in arriving at a zero draft for a code of conduct. In October 2018, despite China’s intensified militarisation of the South China Sea and active use of its facilities there—including exercises involving nuclear-capable bombers at Woody Island, to which the US responded by disinviting China from the RIMPAC exercises—ASEAN for the first time conducted multilateral exercises with China in Zhanjiang. Under Thailand, little diversion from this collaborative course is expected, and the contentious issue will be only reluctantly raised in ASEAN forums.

Instead, the chairmanship will focus on the theme of ‘Advancing Partnership for Sustainability’. Bangkok’s economic agenda includes enhancing regional connectivity, deepening regional digital integration, preparing ASEAN for the fourth industrial revolution, achieving the full operation of the ASEAN Single Window, and concluding the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, which is a mega-free trade agreement aimed at consolidating the existing ASEAN+1 FTAs under a single contract.

Some observers have been worrying that Thailand’s domestic politics might undermine its ASEAN chairmanship. Its internal dynamics are changing rapidly. For example, the Election Commission decided that a by-election would be held in six electoral districts on 21 April because their total vote counts didn’t match the sum of the votes for each candidate.

Predicting the outcome of the March election is a daunting task, but the likely result will be a coalition government with some military control in the parliament. That’s mainly because the Thai constitution allows 250 senators handpicked by the junta to vote along with 500 elected representatives to choose a prime minister. Because at least 376 votes are required to elect a prime minister, the junta will need only 126 votes from the lower chamber if all its senators vote as a bloc. According to unofficial estimates, the pro-junta Phalang Pracharath Party is pocketing 96 votes from the lower house, meaning that it needs an additional 30 votes from other parties to elect a PM it wants.

How will such a coalition government affect Bangkok’s ASEAN chairmanship? As with other coalition governments in other nations, there will be some tensions or conflicts, since different parties usually have different views on or approaches to Thailand’s foreign policy. Such infighting could ultimately cause delays in delivering some agendas.

However, it’s mistaken to assert that internal political clashes would cause Bangkok to turn its back on regional cooperation and integration. For one thing, Thai politicians and military leaders realise the importance of an open system to the country’s future economic growth and development. This is mainly because Thailand’s external trade accounts for 123% of its GDP. Uncertainties created by US–China trade tensions have further tempted Bangkok to look for regional market opportunities. Also, instability in the security realm, such as South China Sea incidents, could disrupt the functioning of transnational production networks that Thailand is part of.

Hence, on the economic front, it’s likely that the Thai chair will push for greater connectivity in physical infrastructure, rules and regulations, and institutions. It’s also likely that the country will play an active role in advancing ASEAN’s master plans for ICT and ASEAN connectivity. Bangkok will continue to push for the conclusion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. The chance of sealing the agreement is likely to be higher in the second half of 2019, after the elections in four of the parties (Australia, India, Indonesia and Thailand) are decided.

China’s pledge to rehabilitate the Belt Road Initiative’s image at the second Belt and Road Forum last month may tempt some Thai leaders to embrace more BRI projects in the future. Seeing itself as a connectivity hub for mainland Southeast Asia, Thailand may decide that BRI projects can better link it with other economies in the region, increasing trade and bringing investment to the country.

So, in short, despite internal conflicts, we will likely see trade, connectivity and the BRI high on Thailand’s agenda.