Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Digital technologies, devices and the internet are producing huge amounts of data and greater capacity to store it, and those developments are likely to accelerate. For law enforcement, a critical capability lagging behind the pace of innovation is the ability and capacity to screen, analyse and render insights from the ever-increasing volume of data—and to do so in accordance with the constraints on access to and use of personal information within a democratic system.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are presenting valuable tools to the public and private sectors for screening big and live data. AI is also commonly considered and marketed as a solution that removes human bias, although AI algorithms and dataset creation can also perpetuate human bias and so aren’t value- or error-free.

In light of the many and varied solutions AI offers, the Australian government is building the necessary policy and regulatory frameworks to pursue the goal of positioning Australia as a ‘global leader in AI’. Recent initiatives include an AI action plan launched in 2021 as part of the digital economy strategy, the CSIRO’s 2019 AI roadmap, and the voluntary artificial intelligence ethics framework, which includes eight principles necessary for AI to be safe and democratically legitimate. In addition, more than $100 million in investment has been pledged to develop the expertise and capabilities of an Australian AI workforce and to establish private–public partnerships to develop AI solutions to national challenges.

AI is being broadly conceptualised by the federal government and many private companies as an exciting technological solution to ‘strengthen the economy and improve the quality of life of all Australians’ by inevitably ‘reshap[ing] virtually every industry, profession and life’. There’s some truth there, but how that reshaping occurs depends on choices, including, for policing, about how data and insights are used and how direct human judgements and relationships can be informed by those technologies, not discounted and disempowered.

In a new ASPI report, released today, I explore some of the limitations on the use of AI in policing and law enforcement scenarios, possible strategies to mitigate the potential negative effects of AI data insights and decision-making in the justice system, and implications for regulation of AI use by police and law enforcement in Australia.

It is problematic, to say the least, that the ethics framework designed to ‘ensure AI is safe, secure and reliable’ is entirely voluntary for both the public and private sectors. And it is not supported by any actual laws specifically addressing the use of AI or other emerging technologies, such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation.

For policing agencies, AI is considered a force-multiplier not only because it can process more data than human brains can conceivably do within required time frames, but also because it can yield insights to complement the efforts of human teams to solve complex analytical problems.

There are many different types and purposes for AI currently under consideration, in trial or in use in various areas of policing globally. Examples include risk assessment of recidivism used to inform parole decisions or to prompt pre-emptive, deterrent police visits to offenders’ homes; public safety video and image analysis, using facial recognition to identify people of interest or to decipher low-quality images; and forensic DNA testing.

AI algorithms, or models, promise to enable processing of high volumes of data at speed while identifying patterns; supercharge knowledge management while (supposedly) removing human bias from the process (we now know that AI can in fact learn and act on human bias); and operate with ethical principles coded into their decision-making.

This promise, however, is not a guarantee.

Holding AI to the ‘safe, secure and reliable’ standard in the Australian ethics framework requires the ability and functionality to comprehensively know and understand how algorithms make decisions and how ethical decision frameworks are coded into an algorithm and its development and training on historical and live datasets.

In fact, there are significant barriers from both a technical and implementation standpoint (for example, the market disincentive of sharing the finer details of how a proprietary AI product works) to achieving these aims.

It’s broadly understood that human bias can compromise both police outcomes (reducing and preventing crime, the successful prosecution of perpetrators of crime, and justice for victims of crime) and the trust from communities that enables effective policing. This can make AI seem a solution; however, if it’s adopted without knowledge of its limitations and potential errors, it has the potential to create more and compounding problems for police.

While researchers are fond of analysing ‘human bias’ in systems, the humanity of individuals also really matters for how they do their work and engage with their communities. It’s a strength of the community policing function, not something to be edited out by technology, no matter how powerful and large the datasets may be. This insight can help shape how policing works with AI and other new technologies, and how human analysts can prevent coded human bias from running unchecked in AI systems.

We can be certain that AI is here to stay. Appropriate regulation of its use in law enforcement scenarios is imperative to mitigate the significant potential impacts on justice outcomes and civil liberties. If Australia wants to ensure AI is safe, secure and reliable, we need at the very least an ethics framework that is compulsory and legally enforceable.

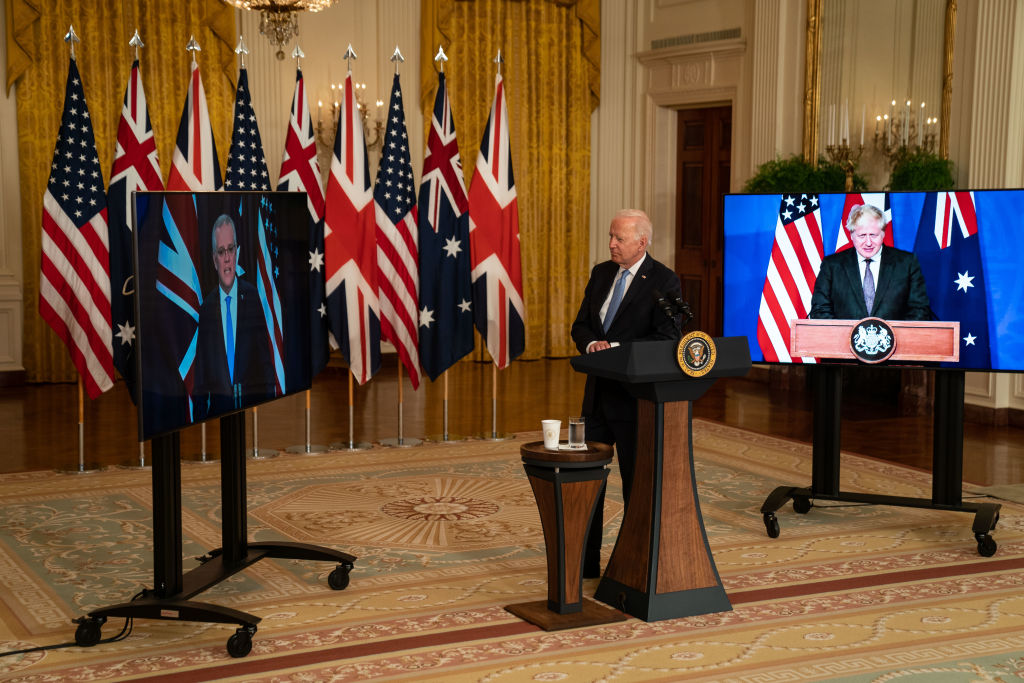

Prime Minister Scott Morrison has added science and technology to the portfolio of the defence industry minister, Melissa Price, signalling closer alignment of the research sector with the defence organisation.

As that’s been done in the context of the new AUKUS partnership, it’s worth noting the United States and British governments’ sharp focus on the defence and national security implications of artificial intelligence. A review of defence innovation in Australia may reveal a need to strengthen policy areas in which we have lagged behind, in particular our lack of strategic direction with a national AI strategy.

The media coverage of the AUKUS pact has mostly focused on the nuclear-powered submarine announcement, but the agreement also emphasises the importance of AI to defence and national security. Australia’s innovation ecosystem will need to take on board developments in the US and the UK.

Britain’s new AI strategy puts defence front and centre after a 2017 industrial strategy and a £1 billion AI sector deal in 2018. By the end of this year, the UK Ministry of Defence intends to publish its own strategy on how it will adopt and use AI. Over the longer term, the National Security and Investment Act will protect national security and monitor investments in AI technology.

In the US, the necessity for speed has been articulated by the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, which was tasked with accelerating the adoption of AI for national security. ‘By 2025, the Department of Defense and the Intelligence Community must be AI-ready,’ it says. This represents a new paradigm in which AI and national security go hand in hand.

Overseen by former Google CEO Eric Schmidt, the AI commission is championing partnerships between technology firms and the Defense Department. A cynic may say that this is to avert the gaze of Congress from antitrust questions in the tech sector, but it is more a sign that technology is increasingly seen as geopolitical.

Elements of the linking of AI and national security most important for Australia are the US treatment of its research enterprise as a national asset, and how the maturation of AI—and its monopolisation by a smaller number of firms—is affecting investment.

Former chief defence scientist Robert Clark and ASPI executive director Peter Jennings have pointed out that US universities are being redefined as an important part of the national security enterprise, making them subject to stronger regulation and oversight. They noted that ‘the current largely open approach of Australian research universities to their international links is significantly exposed’.

If the US positioning of research as a national asset is anything to go by, Australian universities are likely to be repositioned as an element of critical infrastructure. Australian AI research ranks highly in terms of per capita output and quality, in particular the frequency with which research papers are cited. But we have a weak venture capital system and longstanding issues in commercialising our research.

Although there are credible calls to have a wholesale redesign of science and technology research along the lines of the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, some trends will affect these solutions, particularly the sector’s maturation and its monopolisation by fewer firms. How we forge partnerships with international tech firms while we develop our own sector is increasingly important.

The shrinking number of firms involved in AI presents national security risks and compounds problems in defence acquisition, where procurement risk is spread by having diverse suppliers.

Fewer firms possess the human capital and brute computer-processing power to handle the data-processing requirements of AI projects. Graduates are increasingly taking jobs with industry rather than with public research institutions. Investors are putting their money into established companies or, as the OECD put it, making ‘bigger bets on a smaller number of companies as the AI sector matures’.

While technology seems to be getting bigger and to require an endless flood of private and public cash to take it to the stratosphere, it’s clear that the need for speed in defence acquisition is increasing.

In the US, subtle changes are happening in defence innovation to make processes faster and to navigate the procurement labyrinth.

The US Air Force started its own venture capital division, AFVentures, as a division of its technology and acquisition and development group, AFWerx. It has funded an Australia-based AI company, Curious Things, which is trying to redesign the USAF recruitment process. With the Australian defence innovation system under review, it will be interesting to see how these big and small challenges will be incorporated.

As we race towards having an AI edge, there hasn’t been a mature conversation about what the next wave of convergent technology looks like and who should benefit.

The new paradigm of AI and national security will bring out all sorts of arguments that the next wave involves smart dust, photon programming, biotech–AI interfaces, lethal autonomy and the multiverse. But it’s more important to locate Australia’s strategic vision alongside the areas of interoperability and cooperation that are emerging with the US and UK.

Australia urgently needs to elevate its discussion of artificial intelligence from the technical to the strategic. The routine calls for more money to be invested in AI in Australia have lacked bite despite the obvious advantages Australia has in AI, particularly at the research level.

This week’s budget announcement of increased funding for AI initiatives still falls short of what industry says is required. Australia certainly lags behind many similarly sized economies for AI investment, but more depressing is the lack of vision and leadership needed to incubate a robust AI industry. At the same time we need to think about how to mitigate the serious national security challenges that AI driven digital networks pose.

The world has moved on from the national AI strategies that emerged five years ago. The trend appears to be towards developing stronger linkages between states and tech firms. Ex-Google CEO Eric Schmidt has been championing partnerships between technology firms and the US Department of Defense, for example. One of the most interesting ideas that the comprehensive US National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence report outlines is the need for a stronger government role in technology strategy.

Advocacy for a stronger role of government is promoted in other national AI strategies, including France’s. Here, the state is positioned as a vehicle for technological transformation: ‘The state both transforms and shows the way.’ It plays a critical role in ensuring that the public good is preserved, and reduces the trend towards monopolisation in AI.

The idea that the state could play a stronger role presents a challenge to the dominant Australian political discourse of letting the market do its thing. But this laissez-faire approach misunderstands the strong historical relationship between government and the private sector when it comes to technological innovation.

Australia’s approach to innovation, which currently centres around adoption of foreign technology, can be cheaper and faster than building a domestic capacity from the ground up. However, it’s probably time for a more mature conversation about what local industries and sectors need to be incubated, alongside which skills and labour conditions, particularly those relevant to the global race for AI talent.

The US and China certainly recognise that building critical technology capacity is not about just letting the market do its thing, although there are important differences between autocratic and democratic models of state involvement.

The recent signs from the US indicate that the Biden administration will set aside concerns about budget deficits, engage in massive spending and commit to huge investments in breakthrough technologies.

China is seeking to dominate cutting-edge technology and is also spending big, and its success in building authoritarian AI systems will result in profound challenges to democracies. Technology is geopolitical and if Australia continues to be a tech taker it will be left in a profoundly difficult position.

Despite the government’s long-standing rhetoric against deficits, the federal budget has shown signs that it is spending its way to recovery, taking advantage of record-low interest rates. In this, the government may be awakening to how strategic spending can, and must, build sovereign tech capabilities and skills. The challenge will be to ensure that the benefits of investments in AI systems and digital technologies are shared widely across Australian society.

It’s possible that Australian discussions to date have been too focused on the narrative of ‘Will a robot take my job?’. A more interesting and nuanced public conversation might be around the fact that there still so many jobs, despite increasing uptake of AI automation. This would acknowledge the complex drivers of the types and conditions of work available, and the kinds of AI industries we should be encouraging.

The French AI strategy tackles the drivers of technological development by considering the kind of AI future France wants to create in the best interests of all its citizens. This approach recognises that AI is a genuinely transformative technological development and that we must think through its implications for everything from national security to social equity and environmental and economic policy.

At the centre of these issues is the need to understand how the kinds of data we use to build AI systems can have big social and political impacts. It also means understanding how data can be either a national strategic asset or a huge vulnerability.

Without this understanding there’s no possibility of ensuring equity in AI systems. In the interests of national cohesion, Australia should ensure that AI systems we adopt here won’t re-create or exacerbate the inequalities and low productivity that have plagued Western economies and technological systems.

Cedric Villani, the author of the French AI strategy, challenges the view that successful innovation means replicating US approaches. Without strategic thinking and development of our own capabilities, much of our ability to capture value will be dependent upon the intent of those who control AI systems.

This could mean becoming a ‘cyber-colony’ dependent on others for technology and creating a society that is not devoted to humans flourishing within a robust democracy .

In a context where AI globally is being used for mass surveillance for the purposes of advertising, law enforcement and political coercion, Australia must lean into its democratic legacy. This means ensuring that where AI is being used to assist decision-making, those decisions are transparent and explainable. An Australia AI strategy also needs to buttress consumer and privacy rights as well as resist discrimination. All this may be difficult to achieve without a strong domestic AI industry and high levels of AI literacy across society and government.

Australia is a number of years behind other countries on producing a credible AI strategy, although an action plan is in the works. It aims to build on previous solid work by Standards Australia on regulation, CSIRO’s work on a tech roadmap and ethics, as well as the human rights work of the Australian Human Rights Commission. However, it unfortunately also illustrates the continued centrality of adoption in Australia’s tech policy, as well as only a $20 million average annual spend on AI research and industry–research collaboration.

Two years ago CSIRO chair David Thodey likened Australia to Kazakhstan in terms of its inability to harness technology to diversify its economy. Compared to the money being spent globally in AI research, the budget commitment of a total of $124 million over four years is tiny. But more disheartening is the absence of a truly strategic vision that ties together various strands of the digital economy and makes the case for how we should be positioning ourselves in regard to the broader geopolitical contest in the Indo-Pacific, a contest which will play out on the terrain of values as well as that of technology.

It would be a great shame if the Australian government missed this critical moment.

Originally published 29 April 2019.

The 2016 defence white paper and the decades-long integrated investment program will deliver a future force that includes 72 joint strike fighters, several hundred infantry fighting vehicles, nine new frigates and 12 new submarines. F-35 deliveries have started but the ‘future’ frigate and submarine programs were well named: the Hunter-class frigates will turn up, all going well, between 2028 and the early 2040s, and the first Attack-class submarine is scheduled to enter service in 2035, with the 12th in the mid-2050s.

Meanwhile, technology is advancing quickly. There’s been lots of anxiety and hype about lethal autonomous weapon systems—the feared killer robots. But there’s also been a huge amount of experimentation and investment in autonomous and semi-autonomous systems, land, air, sea and undersea.

The US, for example, has demonstrated self-navigating surface and undersurface vessels and numerous land and air systems. The US Navy’s Project Overlord is aiming to deliver 10 large unmanned surface ships by the mid-2020s—before our first frigate enters service. China and Russia are developing similar systems.

The Australian Army is experimenting with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and the RAN with various unmanned systems. Boeing’s ‘Loyal Wingman’ concept UAV is being developed for the RAAF, with a refreshingly rapid timeline that aims for a first flight in 2020. But I don’t see a shift in where Defence’s investment dollars are going that indicates this is more than a hobby for now. That needs to change fast.

Such systems will, at the very least, be essential ‘complementary capabilities’ to the big, complex manned platforms lumbering into the ADF’s inventory over the next 35 years. They may make some of these platforms obsolete, or turn them from frontline combat systems into motherships, providing power and logistics support.

The design concepts of our ‘future force’ need to be worked on now with this in mind.

The other big area in which technological developments and our defence capabilities look badly out of step is in applying ‘narrow artificial intelligence’ to how defence systems are used and to how decisions—tactical, operational and strategic—are made. Supermarkets use this type of AI to optimise inventories to meet customer needs. It displaces humans in factories and call centres and helps us with our internet searches. So, narrow AI is not the potentially species-threatening superintelligence or ‘artificial general intelligence’ Elon Musk has warned about. Think more along the lines of high-speed trading algorithms or Google’s AlphaGo than Will Smith’s enemy in I, Robot.

Technological change is redefining warfare by the attributes of speed, autonomy and precision. Dispersal and rapid reconstitution of combat losses will be required for the future ADF to thrive in such an environment. Speed will be essential not just for weapon systems (for example, hypersonics) but also for command, control and decision-making.

But speed and hierarchies don’t coexist easily or naturally. Hierarchies, by their nature, involve delayed decision-making and sequential decision-making at multiple levels—and they’re the enemies of speed of response. So the organisational structures and processes in ships, squadrons, platoons, brigades and joint taskforce headquarters, across the Defence organisation, in every part of Russell Offices, and right across the lake into the cabinet room will need to change to be fit for future conflict. It will be a wrenching and threatening package of reform and change, as disruptive to current military hierarchy and structures as Amazon has been to the retail industry.

For AI to take back the time advantage from adversaries using high-speed precision weapons, it will need to find its way into the ADF’s existing systems and platforms soon—well before the first new frigate or submarine gets wet.

Warfare through history is a story of measure and countermeasure. While the combat systems that are on our Anzac-class frigates and air warfare destroyers can track and defeat numerous simultaneous missile threats, the speed of decision-making on board the ships depends on multiple human intervention points. Myriad pieces of information from shipboard and offboard sensors, intelligence and data need to be fused into a coherent picture for the crew and captain.

No matter how skilled the console operators, principal warfare officers or commander, and no matter how highly developed the combat systems are, the time-and-motion problem posed by numerous supersonic and hypersonic threats will be intense.

AI will be essential for supporting high-speed data analysis and decision-making. Training AI decision-support algorithms on the mass of data that a ship’s combat system and command chain will have available won’t just allow the vessel to use its onboard defence systems to defeat attacks; it will also facilitate rapid cueing of offboard systems—say, on a nearby F-35, Growler electronic attack aircraft, P-8 patrol aircraft, accompanying surface vessels or even unmanned systems—to defend the ship and attack the adversary’s weapons, launch sites, targeting systems, and command-and-control chain. And it will allow the AI-enabled decision system to draw on masses of historical data and intelligence relevant to the environment and threats being faced.

In the world of high-speed, autonomous and precision weapon systems, AI can return the advantage to the defender by enabling its systems to make faster and better informed decisions than the attacker’s systems. It can support an asymmetric response that will give the defender more options than simply shooting faster than the attacker.

Concepts for employing this aid to high-speed decision-making in existing ADF platforms and systems are urgently needed. To put these concepts into action, equally urgent design, development and investment is required to retrofit systems like the Anzacs and AWDs, and also the command-and-control systems already operating across the ADF. The Anzacs, the Collins submarines and the AWDs will be frontline combatants for decades, so it’s essential to equip them to survive and be effective over that timeframe. AI-enabled onboard decision-support systems must be a part of the plan.

A defining opportunity is the planned $2.5 billion investment in AIR 6500 to acquire a command-and-control system for integrated air and missile defence that will operate from the level of protecting deployed army units right up to protecting whole joint taskforces, combining army, air force and navy units and systems. This system must have AI built in from the concept stage.

That will be key to taking advantage of the masses of data collected and required by ADF units, along with historical data that enables AI systems to learn and to apply that knowledge to new environments.

It’s absolutely feasible to retrofit autonomy and AI algorithms into military platforms and control systems. The US Air Force is converting more F-16 fighters to autonomous aircraft, while DARPA is bringing AI-enabled tools into existing aircraft so that each can control multiple drones. Lockheed Martin’s Sikorsky now has years of experience in developing ‘software and hardware that bring autonomous flight to the cockpit’ of its Black Hawk helicopters.

It’s great to muse about the wonders of Australia’s $200 billion ‘future force’, but our time would be much better spent on the urgent new work and thinking required to make our existing force effective in the environment it will face in the early and mid-2020s.

That means loving the force you have—acting now to develop the concepts for use of AI across the ADF, and investing to retrofit the systems and platforms that will remain in service for decades.

That will prepare us for those bright sunlit days when the Hunter and Attack classes become real.

The public discourse on artificial intelligence in the military context tends to get messy very quickly. There seems to be an AI variant of Godwin’s law (which holds that as any online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison being made to Nazis approaches 1) at work, except in this case it’s the probability that a reference will be made to killer robots or the Terminator movies’ Skynet. So it was useful to attend a recent conference on ethical AI for defence to gain a better understanding of where things currently stand.

The conference was jointly sponsored by the Defence Science and Technology Group, the air force’s Plan Jericho team, and the Trusted Autonomous Systems Defence Cooperative Research Centre, which is largely funded by the Department of Defence. It’s not surprising, then, that the overall tenor of the conference was that the ethical issues are significant but manageable.

There was broad representation, ranging from defence practitioners to AI developers, philosophers, ethicists and legal experts, resulting in a range of opinions. Granted, some were sceptical of the value of AI. And occasionally it felt like some philosophers were mainly interested in posing increasingly exquisite variations of the trolley problem (do I save the homeless orphans or nuns pushing prams from impending doom?).

Overall, however, there was broad consensus on key issues. One is that when we’re considering AI for defence uses, we’re talking about ‘narrow’ AI—that is, applications optimised for particular problems. Narrow AI is already deeply embedded in our lives. General AI—that is, a system with similar cognitive abilities to humans—is still a long way off. According to one presenter, over the past 50 years predictions for when that would be achieved have stubbornly remained 40 years in the future. Part of the messiness in public discussion tends to stem from a conflation of narrow and general AI.

It is perhaps useful to distinguish between three levels of ethical issues, each of which is distinct and needs to be addressed by different people in a different way.

The first are the macro-ethical issues, such as the implications of the ‘AI singularity’, the point at which machines become smarter than humans (if we do actually reach it in 40 years’ time). Or the question of whether autonomous systems replacing humans on the battlefield makes it easier for leaders to choose to use military means to resolve disagreements. Ultimately these are questions that must be resolved by society as a whole.

But it is important for Defence to have the ability to inform the broader discussion so that our service people aren’t prevented from adopting AI while facing adversaries that have exploited its capability advantages. To do this, Defence needs to have credibility by demonstrating it understands the ethical issues and is acting ethically.

At the other end of the scale are the daily, micro-ethical issues confronted by the designers and users of AI-driven systems in ensuring they embody our values. Certainly, this is not a mechanical task. While it’s relatively easy to develop a list of values or principles that we want our AI-driven systems to adhere to (privacy, safety, human dignity, and so on), things get tricky when we try to apply them in particular tools.

That’s because, in different circumstances, those principles may have different priority, or they may in fact be contradictory. But the developer or user of the system doesn’t need to resolve the macro questions in order to satisfactorily resolve the micro issues involved in, say, developing an AI-driven logistics application that distributes resources more efficiently.

In between are the medium-sized, or enterprise-level, ethical issues. For example, there are ethical challenges as we move to a business model in which people are consuming the outputs of AI, rather than generating those outputs themselves. If the point of keeping a human in—or at least on—the decision loop is to ensure that human judgement plays a role in decision-making, how do you make sure the human has the skill set to make informed judgements, particularly if you expect them to be able to overrule the AI?

Preventing de-skilling is more than an ethical issue; it’s about designing and structuring work, training and career opportunities, and human identity. So ethics has to be embedded in the way Defence thinks about the future.

Once you divide the problem space up, it doesn’t seem so conceptually overwhelming, particularly when many of Defence’s ethical AI issues are not new or unique. Another area of consensus is that the civil sector is already dealing with most of those issues. Designers of self-driving cars are well aware of the trolley problem. So Defence isn’t in this alone and has models to draw upon.

Moreover, with a human in the loop or on the loop, even in specifically military applications (employing lethal weapons, for example) the ethical use of systems employing AI isn’t fundamentally different from the ethical use of manned systems, for which the ADF has well-established processes. Certainly those frameworks will need to evolve as AI becomes central to defeating evolving threats (such as hypersonic anti-ship missiles), but there’s already something to build upon.

In large organisations like Defence, the challenge facing innovators—like those seeking to leverage the opportunities offered by AI—is that they always face long lists of reasons why their ideas won’t work. After all, identifying risks is at the heart of Defence.

Encouragingly, islands of innovative excellence—such as Plan Jericho and the Trusted Autonomous Systems Defence CRC—have shown that they are capable of forging new approaches to developing and delivering defence capability.

So, while it’s important for Defence to understand and address the ethical challenges posed by AI, it’s just as important to not let those challenges blind it to the opportunities offered by AI and discourage our defence planners from pursuing them.

The 2016 defence white paper and the decades-long integrated investment program will deliver a future force that includes 72 joint strike fighters, several hundred infantry fighting vehicles, nine new frigates and 12 new submarines. F-35 deliveries have started but the ‘future’ frigate and submarine programs were well named: the Hunter-class frigates will turn up, all going well, between 2028 and the early 2040s, and the first Attack-class submarine is scheduled to enter service in 2035, with the 12th in the mid-2050s.

Meanwhile, technology is advancing quickly. There’s been lots of anxiety and hype about lethal autonomous weapon systems—the feared killer robots. But there’s also been a huge amount of experimentation and investment in autonomous and semi-autonomous systems, land, air, sea and undersea.

The US, for example, has demonstrated self-navigating surface and undersurface vessels and numerous land and air systems. The US Navy’s Project Overlord is aiming to deliver 10 large unmanned surface ships by the mid-2020s—before our first frigate enters service. China and Russia are developing similar systems.

The Australian Army is experimenting with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and the RAN with various unmanned systems. Boeing’s ‘Loyal Wingman’ concept UAV is being developed for the RAAF, with a refreshingly rapid timeline that aims for a first flight in 2020. But I don’t see a shift in where Defence’s investment dollars are going that indicates this is more than a hobby for now. That needs to change fast.

Such systems will, at the very least, be essential ‘complementary capabilities’ to the big, complex manned platforms lumbering into the ADF’s inventory over the next 35 years. They may make some of these platforms obsolete, or turn them from frontline combat systems into motherships, providing power and logistics support.

The design concepts of our ‘future force’ need to be worked on now with this in mind.

The other big area in which technological developments and our defence capabilities look badly out of step is in applying ‘narrow artificial intelligence’ to how defence systems are used and to how decisions—tactical, operational and strategic—are made. Supermarkets use this type of AI to optimise inventories to meet customer needs. It displaces humans in factories and call centres and helps us with our internet searches. So, narrow AI is not the potentially species-threatening superintelligence or ‘artificial general intelligence’ Elon Musk has warned about. Think more along the lines of high-speed trading algorithms or Google’s AlphaGo than Will Smith’s enemy in I, Robot.

Technological change is redefining warfare by the attributes of speed, autonomy and precision. Dispersal and rapid reconstitution of combat losses will be required for the future ADF to thrive in such an environment. Speed will be essential not just for weapon systems (for example, hypersonics) but also for command, control and decision-making.

But speed and hierarchies don’t coexist easily or naturally. Hierarchies, by their nature, involve delayed decision-making and sequential decision-making at multiple levels—and they’re the enemies of speed of response. So the organisational structures and processes in ships, squadrons, platoons, brigades and joint taskforce headquarters, across the Defence organisation, in every part of Russell Offices, and right across the lake into the cabinet room will need to change to be fit for future conflict. It will be a wrenching and threatening package of reform and change, as disruptive to current military hierarchy and structures as Amazon has been to the retail industry.

For AI to take back the time advantage from adversaries using high-speed precision weapons, it will need to find its way into the ADF’s existing systems and platforms soon—well before the first new frigate or submarine gets wet.

Warfare through history is a story of measure and countermeasure. While the combat systems that are on our Anzac-class frigates and air warfare destroyers can track and defeat numerous simultaneous missile threats, the speed of decision-making on board the ships depends on multiple human intervention points. Myriad pieces of information from shipboard and offboard sensors, intelligence and data need to be fused into a coherent picture for the crew and captain.

No matter how skilled the console operators, principal warfare officers or commander, and no matter how highly developed the combat systems are, the time-and-motion problem posed by numerous supersonic and hypersonic threats will be intense.

AI will be essential for supporting high-speed data analysis and decision-making. Training AI decision-support algorithms on the mass of data that a ship’s combat system and command chain will have available won’t just allow the vessel to use its onboard defence systems to defeat attacks; it will also facilitate rapid cueing of offboard systems—say, on a nearby F-35, Growler electronic attack aircraft, P-8 patrol aircraft, accompanying surface vessels or even unmanned systems—to defend the ship and attack the adversary’s weapons, launch sites, targeting systems, and command-and-control chain. And it will allow the AI-enabled decision system to draw on masses of historical data and intelligence relevant to the environment and threats being faced.

In the world of high-speed, autonomous and precision weapon systems, AI can return the advantage to the defender by enabling its systems to make faster and better informed decisions than the attacker’s systems. It can support an asymmetric response that will give the defender more options than simply shooting faster than the attacker.

Concepts for employing this aid to high-speed decision-making in existing ADF platforms and systems are urgently needed. To put these concepts into action, equally urgent design, development and investment is required to retrofit systems like the Anzacs and AWDs, and also the command-and-control systems already operating across the ADF. The Anzacs, the Collins submarines and the AWDs will be frontline combatants for decades, so it’s essential to equip them to survive and be effective over that timeframe. AI-enabled onboard decision-support systems must be a part of the plan.

A defining opportunity is the planned $2.5 billion investment in AIR 6500 to acquire a command-and-control system for integrated air and missile defence that will operate from the level of protecting deployed army units right up to protecting whole joint taskforces, combining army, air force and navy units and systems. This system must have AI built in from the concept stage.

That will be key to taking advantage of the masses of data collected and required by ADF units, along with historical data that enables AI systems to learn and to apply that knowledge to new environments.

It’s absolutely feasible to retrofit autonomy and AI algorithms into military platforms and control systems. The US Air Force is converting more F-16 fighters to autonomous aircraft, while DARPA is bringing AI-enabled tools into existing aircraft so that each can control multiple drones. Lockheed Martin’s Sikorsky now has years of experience in developing ‘software and hardware that bring autonomous flight to the cockpit’ of its Black Hawk helicopters.

It’s great to muse about the wonders of Australia’s $200 billion ‘future force’, but our time would be much better spent on the urgent new work and thinking required to make our existing force effective in the environment it will face in the early and mid-2020s.

That means loving the force you have—acting now to develop the concepts for use of AI across the ADF, and investing to retrofit the systems and platforms that will remain in service for decades.

That will prepare us for those bright sunlit days when the Hunter and Attack classes become real.

Perhaps, the real ‘arms race’ in artificial intelligence (AI) is not military competition but the battle for talent. Since the vast majority of the world’s top AI experts remain in the US, China is starting out from a position of clear disadvantage in this fight. The New Generation AI Development Plan, released in July 2017, acknowledged, ‘cutting-edge talent for AI is far from meeting demand’. This initial program called for China to ‘accelerate the training and gathering of high-end AI talent’, recognised as an objective ‘of the utmost importance’. Indeed, Chinese leaders are determined to catch up through leveraging a range of talent plans and new educational initiatives.

China’s AI talent insurgency is already underway. In accordance with this plan, China is creating new technical training programs, engaging in aggressive recruitment and constructing AI as an academic discipline.

In early April, China’s Ministry of Education released the ‘Artificial Intelligence Innovation Action Plan [for] Institutions of Higher Learning’ (高等学校人工智能创新行动计划). The plan calls for Chinese universities to become ‘core forces for the construction of major global AI innovation centres’ by 2030.

To ‘perfect’ its AI talent training system, China intends to improve the layout of the discipline, strengthen professional development, improve the construction of teaching materials, strengthen personnel training, launch universal education in AI, support innovation and entrepreneurship, and expand international exchanges and cooperation.

By 2020, China intends to establish at least 50 AI academic and research institutes, while also pioneering an interdisciplinary ‘AI+’ approach. Within the past year, the Chinese Academy of Science, Beihang University and Nanjing University, among others, have already established new AI degree programs and institutes.

The plan also calls for Chinese scholars to ‘enhance their international influence’ through taking up ‘important positions in international academic organisations’, while ‘actively participating in the formulation of international rules related to AI’.

Of note, the plan includes a focus on military–civil fusion (军民融合) in AI education:

Accurately seize upon military–civil fusion’s deep development direction, development laws and development priorities; give full play to the advantages and comprehensive disciplinary characteristics of universities in basic research and personnel training; actively integrate them into the national military–civilian fusion system; and incessantly promote the two-way transfer and conversion of applications for military–civil technologies.

The plan continues on the theme of military–civil fusion:

Promote deep military–civil fusion. Focusing on information technology, taking AI technologies as a breakthrough point, and turning towards highly effective information acquisition, semantic understanding, and information utilisation; take unmanned systems and man-machine hybrid systems as models; build a military–civil shared AI technology innovation base; strengthen the cultivation of military–civil fusion AI innovation research projects; promote relevant technological innovations in colleges and universities to drive military superiority and information superiority …

Here’s an example of how China’s quest for AI talent is already on track to become a reality.

Also in early April, a new educational initiative was established in China, launched by Kai-Fu Lee in partnership with China’s Ministry of Education and Peking University. This summer, 300 top students will receive special training in AI from Kai-Fu Lee and other experts, including Cornell professor John Hopcroft. Kai-Fu Lee notes, ‘If these professors each teach a class of 400 students in fall and spring, that would graduate thousands of students for employment in 2019.’

This program will train at least 500 AI teachers and 5,000 AI students in top universities in five years. In the future, this model might also be expanded to universities across China, scaling up the training of AI experts and potentially enabling a long-term talent advantage.

It remains to be seen whether China’s quest for AI talent will be successful, but these active efforts reflect a clear recognition of the strategic importance of human capital in this domain.

In 2017, a US Department of Defense study of the future operating environment described artificial intelligence (AI) as the most disruptive technology of our time.

In this environment, says the report:

big data techniques interrogate massive databases to discover hidden patterns and correlations that form the basis of modern advertising—and are continually leveraged for intelligence and security purposes by nation states and non-state entities alike.

The potential applications of artificial intelligence, and the deep-learning capabilities it brings, may be one of the most profound artefacts of the fourth industrial revolution. Informed and experienced experts such as Secretary James Mattis and US Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work are questioning whether AI will change not just the character, but also the nature of war. That highlights just how disruptive this technology is likely to be for society and commerce, as well as for human competition and conflict.

In future conflicts, we can expect decision cycles to become faster than human cognition can process. Military command and control—and strategic decision-makers—will need AI that can process information and recommend options for decisions faster (or of higher quality) than can the enemy.

And as I’ve written previously, military organisations will contain thousands or even tens of thousands of unmanned and robotic systems, all with some type of AI. These swarms will demand AI-assisted command and control, as will the other composite human-automated military formations that are likely to exist in future areas of conflict.

While there’s a need to build capacity within the Defence organisation, the guiding principles apply to a wider national security community. Defence exists in an ecosystem of government organisations working towards national objectives. It’s imperative to quickly introduce AI to support decision-making in this joined-up environment. Then, immediate action is required for Defence (the department and the ADF) to rapidly increase its understanding of the applications of AI, and to contribute to a national approach.

Frank Hoffman recently proposed that military organisations may be at the dawn of a seventh revolution in military affairs that he calls the ‘autonomous revolution’. Underpinned by exponential growth in computer performance, improved access to large datasets, continuing advances in machine learning and rapidly increasing commercial investment, the future application of AI and machine learning may change military organisations and, more broadly, how nations prepare for war.

However, as Max Tegmark has written, there’s debate among AI researchers about whether human-level AI is possible, and when it might appear. The nearest estimates are ‘in a few decades’, with others predicting ‘not this century’ and ‘not ever’.

But, assisted, augmented and autonomous intelligence capabilities are already in use or can be expected over the coming decade. AI needn’t replicate human intelligence to be a powerful tool. The intellectual preparation of Defence personnel, and that of the wider national security community, to effectively use AI must begin now.

The first of four key imperatives is to start educating Defence and other national security personnel about AI. A Belfer Center report finds that it’s vital for non-technologists to be conversant with the basics of AI and machine learning. The aim is to develop baseline AI literacy among more Defence and national security leaders to supplement the expertise of the few technical experts and contractors who design and apply algorithms. Reading lists, residential programs and online courses, as well as academic partnerships and conferences, will help.

Defence education must be adapted to deliver greater technical literacy so personnel better understand machine learning and AI. This will permit a wider institutional capacity to effect quality control and address the risks of misbehaving algorithms. Personnel must be educated about the ethical issues of using AI for national security purposes. The overarching aim must be to develop a deep institutional reservoir of people who understand the use of AI, and who appreciate how human and AI collaboration can be applied most effectively at each level of command.

The second imperative is for Defence and other agencies to move beyond limited experimentation and thinking in key areas to broader explorations of how to use AI. This might include finding new ways for the national security community to use AI to work together more effectively. It may also allow the use of AI to support decision-making that could drive changes to the organisation of military and non-military elements in national security.

Some aspects of this exploration will require leaps of faith in assessing how capable AI will be in the future. Between the wars, the German army used fake tanks to develop its combined arms operating systems. So too might we use anticipated future capabilities to build new integrated national security and Defence operating systems using AI.

Potentially, this exploration could even permit consideration of significant changes in strategic decision-making processes and organisations—mostly leftovers from second and third industrial revolution mindsets.

The third imperative is for Defence to deepen collaboration with external institutions working on AI applications. All of the Group of Eight universities in Australia conduct AI research and teach applications. A number have partnerships with international institutions, including some who do work for foreign military and security agencies. They could help Defence, and other government agencies, explore the use of AI to support operational capabilities, for decision-making in directing and running operations and in other strategic functions such as education. Broad collaborative research with our closest allies will permit sharing of best practice and offers small nations like Australia the opportunity to develop bespoke applications that complement—not copy—overseas innovations.

Eventually, this could (and probably should) lead to a fourth imperative, the development of an AI equivalent of the Australian Naval Shipbuilding Plan, and a focus for a sovereign capability in AI research and development. Such a national approach is important because it might provide resourcing for further collaboration between universities and government and commercial entities. It may provide the basis for a larger national industry to support non-military AI functions.

Finally, if robotics is included, it may provide a basis to mobilise national effort if that’s necessary in the coming decades. Australia sits at the end of a long supply line for almost every element of sophisticated weaponry. Our successors may thank us if we have the forethought to develop an indigenous capacity to design and construct (using additive manufacturing) swarms of autonomous systems.

Sitting back and observing foreign developments isn’t an effective strategy. An aggressive national and departmental program of research, experimentation and educating Defence and other national security personnel is required. The knowledge for such a program exists in our universities and changes in the regional and global security environment provide the strategic drivers for action.

Leveraging potential capabilities, we must start to educate our people now, and we must develop a national sovereign capacity to harness AI for national security purposes. In this way we might develop a truly brilliant future ADF.

On 23 October, Philippine Secretary of Defense Delfin Lorenzana announced the end of the five-month battle for Marawi, after the Armed Forces of the Philippines defeated Islamic State–affiliated militants who had held the city since 23 May.

Philippine authorities discovered that IS central provided more than US$1.5 million (A$1.9 million) to finance the siege. Funds were sent via Indonesia through Western Union. Large amounts were also looted from local banks and private homes. Bundles of money were found in buildings around the city, including 800,000 pesos (A$20,000) stashed in one building and 300,000 pesos (A$7,800) and a bag of gold jewellery in another. In June, 52 million pesos (A$1.3 million) in cash was recovered from a house occupied by terrorist sympathisers.

These discoveries are a timely reminder of the importance of detecting, disrupting and denying terrorism financing, and the need for regional cooperation between Australia and Southeast Asian countries to help do so. Fortunately, regional counterterrorism financing (CTF) cooperation has been enhanced over the past two years. Australia is playing a leading role in these efforts.

Indeed, against the backdrop of the Marawi liberation, the third CTF Summit, co-hosted by AUSTRAC—Australia’s financial intelligence unit—and its Indonesian and Malaysian counterparts, PPATK and Bank Negara Malaysia, was held in November in Kuala Lumpur (KL).

The third summit built on the success of the two previous summits, held in Sydney in 2015 and Bali last year. The event has grown—the KL summit attracted participants from 32 countries, compared to 26 in Bali and 19 in Sydney. It has also matured, thanks to relationships built over the past two years. That’s not just from attendance at the annual summit, but also through three working groups—focusing on financial intelligence, technological innovation, and education and community outreach—that are doing important work in between summits. For example, the financial intelligence working group met face to face three times, and by phone monthly, between the Bali and KL summits. The group produced the world’s first regional risk assessment (RRA) on terrorism financing last year, which is an important basis for intelligence-led CTF actions.

At KL, a new RRA on terrorism financing in the not-for-profit sector was released. The assessment downgraded the sector’s risk from high to medium compared to the earlier RRA. That’s because the deeper assessment, based partly on several national non-profit organisation (NPO) risk assessments (including Australia’s), found fewer cases of terrorism financing through NPOs than expected. A clearer picture of the risk environment is a welcome development. However, as I’ve argued before, the risk downgrade doesn’t mean we should be complacent.

At the summit, Justice Minister Michael Keenan announced the establishment of the South East Asia Counter Terrorism Financing Working Group (SEA CTFWG). This group will be co-led by AUSTRAC and the Philippines’ Anti-Money Laundering Council and also involve financial intelligence units from Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore and Thailand. Keenan noted that this is the first of a series of initiatives to support AUSTRAC and its regional partners to block funding to IS and other terrorist groups in Southeast Asia. The Turnbull government provided a $4.6 million package over three years for these initiatives in September.

The SEA CTFWG should seek to improve intelligence sharing between regional countries to better detect funds transfers and map terrorist networks. It’s well placed to do that thanks to relationships built up since the Sydney summit.

Between now and the fourth summit, to be held in Thailand in 2018, progress should be made in two key areas: better harnessing technology and building public–private partnerships.

Technologies such as blockchain, big data and artificial intelligence present opportunities to more effectively detect criminal activity among the flood of data available to government and business. However, this promise is yet to be met, as the successful deployment of these technologies to fight financial crime has been limited in practice. At the same time, financial technology is advancing rapidly, and new payment systems and virtual currencies are creating new opportunities for terrorist financiers and criminals.

To foster the better use of technology, the inaugural International Financial Intelligence Unit Codeathon was held before the summit. Sixty-nine participants from 11 countries sought to address a range of financial crime challenges through technological solutions. Following the success of this initiative, AUSTRAC announced that an ASEAN–Australia Codeathon will be held in Sydney in March 2018 in the run-up to the ASEAN–Australia Special Summit.

Public–private partnerships to counter terrorism financing and other financial crimes are in their infancy, but those countries yet to develop such initiatives should look to do so. Existing initiatives such as Australia’s Fintel Alliance can provide examples, and ASPI will continue its focus on identifying ways to improve information sharing between the public and private sectors next year.

CTF efforts are an important policy tool to counter the growing terrorist threat in Southeast Asia. The CTF Summit, working groups, Codeathons, and new SEA CTFWG provide an excellent basis for this, but in the current environment there’s much work to do.

Getting a handle on the ‘cyber’

It’s been a big week in internet regulation, with unsavoury activities being plugged left and right. GoDaddy, a major domain registration service, evicted the Daily Stormer from its platform, after an article was posted on the website slandering one of the women killed in Charlottesville, Virginia. The website was linked with white supremacists who organised the rally that turned violent. The site moved to Google, which quickly announced that it would also cancel the Daily Stormer’s shiny new domain name registration.

In between the exodus from GoDaddy to Google, Anonymous also apparently took control of the website (leaving its trademark #tangodown post behind), although the fact that all the hateful content remained untouched left eyebrows raised. @YourAnonNews, what amounts to a representative for the collective, issued a series of denials against the claim, and took a couple of jabs at the Daily Stormer for trying to plant a false flag. Discord, a free chat and VoIP service, has also shut down a number of accounts associated with white supremacists.

In Australia, the federal government is formally advancing its agenda to make telecommunications and internet service providers the ‘gatekeepers’ of the internet. The government has accepted the recommendations of a joint parliamentary committee for new telecommunications legislation, which will impose an obligation on telcos and internet service providers to actively protect themselves and customers on their networks from unauthorised access and interference.

Special Adviser to the Prime Minister on Cyber Security Alastair MacGibbon is looking at ways to get a handle on the proliferation of cyber-hyphenated terms. Last Friday, he convened a roundtable discussion on an early draft of a government ‘Cyber security lexicon’, which aims to build a common cyber vocabulary among all the different groups that are involved in cybersecurity.

Which came first, data or AI?

Backchannel has gone into how Baidu’s rich trove of behavioural data from China’s incomparably large customer base might push the company to the top of the global race to develop AI. Theorising about future trends aside, it’s notable that Baidu’s past success in this field has attracted leading figures from Stanford and Microsoft, and China is betting big when it comes to AI research.

AI research in general has continued to hit major milestones. A bot from Elon Musk–backed company OpenAI has added Dota 2 to the list of solved problems in AI research (chess, Go and poker have already been cracked, and StarCraft seems to be next on the list). The bot crushed one of the world’s best players at the annual tournament in a best-of-three matches contest—winning the first in less than 10 minutes (in a game where an average round takes 40–60 minutes). Elon Musk has praised the accomplishment as a landmark in AI research, though that comes in stark contrast to his other tweets this week on the risks of AI.

Malware, malware everywhere

‘Biohackers’ from the University of Washington have encoded DNA with malware that can exploit software in the DNA sequencing process. The news has picked up a lot of buzz this week, particularly about how it might’ve put some sci-fi authors out of work, but the researchers have also been criticised for using deliberately introduced vulnerabilities that make the reality less sexy than the headline might imply.

Good old-fashioned hacking

HBO hacker ‘Mr Smith’ has dumped three sets of HBO files online, including Game of Thrones scripts and a log of emails from one of HBO’s VPs, and demanded a ransom of US$6 million, by one estimate. Among the data dumped were the personal details of several Game of Thrones stars, and other sensitive contact information. HBO has reportedly decided to pay some of the ransom—offering US$250,000 and spinning it as a ‘bug bounty’ rather than a ransom payment.

Marcus Hutchins, or @MalwareTechBlog, has pleaded not guilty to the various counts of computer crime and fraud he’s been accused of by US prosecutors. His next hearing will be held on 17 October 2017, and in the meantime he’s been barred from leaving the US, though he has been granted the right to use the internet.

Cybersecurity by the numbers

Dashlane, a password management software vendor, has conducted a review of the password practices of the web’s 40 most popular websites—and found Amazon, Google, Instagram, LinkedIn, Venmo and Dropbox to fail the most basic ‘password power’ criteria. Curiously, the criteria on which the researchers assessed password power were the same criteria that were recently renounced by their initial creator (after decades of criticism) as incorrect and unhelpful.

And lastly, BDO and AusCERT have started taking responses on board for their second annual Cyber Security Survey. The survey closes on 15 September, and interested individuals can take part here or here.