Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Just over 20 years ago, Spanish naval personnel operating in the Arabian Sea intercepted a merchant ship sailing from North Korea to the port of Aden. Acting on intelligence from their US counterparts, the interdiction team discovered a consignment of Scud missiles hidden on board the vessel, the So San. At the time, Washington’s concern was that the Scud missiles were bound for Iraq and preparations were building in the region for the coalition’s ill-fated intervention against Saddam Hussein’s military.

Lacking any legal basis to seize the consignment, the Spanish team could do little more than release the So San and let it sail, after receiving an undertaking from the Yemeni government that the missiles wouldn’t be transferred to any third party. From that point on, a realisation took hold that the international community needed a new architecture for counterproliferation.

What followed was the establishment of a landmark international strategy aimed at controlling the spread of chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear and high-consequence explosive (CBRNE) technologies: the Proliferation Security Initiative, which this year marked its 20th anniversary. Over the past two decades, the initiative has consolidated an alliance of more than 106 countries committed to preventing the spread of CBRNE.

However, much has changed in the geopolitical and technological landscape since the heady days of the 2000s. While the war on terror concentrated on non-state actors and an isolated ‘axis of evil’, great-power competition has returned as a central focus of international security. And although missile components and dual-use centrifuges are still being hunted down, non-proliferation is today equally concerned with materials that are smuggled with much more ease. This is especially true with the tools of dual-use chemistry and synthetic biology.

In the same year as the So San incident, a group of scientists constructed the first entirely artificial virus, a chemically synthesised strain of polio. Three years later, reverse genetics was used to recreate H1N1 ‘Spanish’ influenza, which had killed more than 50 million people in the years following the First World War. Since then, pox viruses, coronaviruses, avian flu and several other pathogens have been revived, amplified or modified into forms that can evade herd immunity or render established medical countermeasures obsolete. The technologies used to produce these infectious agents are much smaller than anything recently interdicted on the high seas: whole genome sequencers that can be held in the palm of one’s hand, chemical reagents that can be ordered online, and a host of other products that don’t need to be transported on a slow-moving ship.

In the past year, the life sciences have been further turbocharged by the latest chapter of technological advancement: the newly emergent platforms of artificial intelligence. With the debut of novel large-language models in late 2022, the public has seen minor previews of how those with malicious intent could apply AI tools to CBRNE. An exercise in Massachusetts showed how a large-language model could help students without any scientific training construct synthetic versions of the causative agents of smallpox, influenza, Nipah virus and other diseases. Elsewhere, researchers using generative AI for drug discovery found that they could also design a range of nerve agents, including VX. Discussion has even circulated of integrating AI into nuclear launch systems, a kind of digital dead hand for the new age. To all of this was added a slew of articles on AI-enabled high-consequence munitions, including fire-and-forget hypersonic missiles, autonomous loitering munitions and unmanned attack vehicles.

While much debate has erupted over the existential risk posed by AI platforms, some have argued that these concerns are either non-specific or alarmist. We, the authors, are investigating precisely how AI could accelerate the proliferation of CBRNE, and how such applications might be realistically controlled. To this end, we will be seeking expert opinions on how generative AI could lower informational barriers to CBRNE proliferation, or add new capabilities to existing weapon systems. As both researchers and clinicians, our concern relates primarily to human security, and what can be done to safeguard international public health. We hope to understand how counterproliferation professionals are confronting this new era, and what new concepts will be needed to protect human life and prosperity.

Next year, Australia will host the Proliferation Security Initiative’s Asia–Pacific exercise rotation, Pacific Protector. Air force and naval assets will be deployed across a vast expanse of ocean at a time of increased tension over a place central to AI and its underlying technologies: the Taiwan Strait. While the exercise will have several enduring uses that will benefit the Asia–Pacific, it is undeniable that the task of countering CBRNE proliferation has fundamentally changed since the initiative’s establishment.

States, non-state actors and individuals now have access to technologies and informational aids that used to be the stuff of science fiction. How policymakers, researchers and practitioners confront weapons proliferation in the new age of AI will have long-term consequences for human security in this region, and across the globe.

You may not be interested in artificial intelligence, but it is interested in you. Today, you might have used AI to find the quickest route to a meeting through peak-hour traffic and, while you used an AI-enabled search to find a decent podcast, driver-assist AI might have applied the brakes just before you back-ended the car in front, which braked suddenly for the speed camera attached to AI-controlled traffic lights. In the aftermath, AI might have helped diagnose your detached retina and recalculated your safe-driving no-claim bonus.

So, what’s the problem?

The problem—outlined in my new report released by ASPI today—is that AI-enabled systems make many invisible decisions affecting our health, safety and wealth. They shape what we see, think, feel and choose, they calculate our access to financial benefits as well as our transgressions, and now they can generate complex text, images and code just as a human can, but much faster.

It’s unsurprising that moves are afoot across democracies to regulate AI’s impact on our individual rights and economic security, notably in the European Union.

But if we’re wary about AI, we should be even more circumspect about AI-enabled products and services from authoritarian countries that share neither our values nor our interests. The People’s Republic of China is an authoritarian power hostile to the rules-based international order that routinely uses technology to strengthen its own political and social stability at the expense of individual rights. In contrast to other authoritarian countries, such as Russia, Iran and North Korea, China is a technology superpower with global capacity and ambitions and is a major exporter of effective, cost-competitive AI-enabled technology.

In a technology-enabled world, opportunities for remote, large-scale foreign interference, espionage and sabotage —via internet and software updates—exist at a ‘scale and reach that is unprecedented’. AI-enabled industrial and consumer goods and services are embedded in our homes, workplaces and essential services. More and more, we trust them to operate as advertised, to always be there for us and to keep our secrets.

Notwithstanding the honourable intentions of individual vendors of Chinese AI-enabled products and services, they are subject to direction from PRC security and intelligence agencies. So democracies need to ask themselves, against the background of growing strategic competition with China, how much risk they are prepared to bear. Three kinds of Chinese AI-enabled technology require scrutiny:

The report focuses on the first category and looks at TikTok through the prism of the espionage and sabotage risks posed by such apps.

The underlying dynamic with Chinese AI-enabled products and services is the same as that which prompted concern over Chinese 5G vendors: the PRC government has the capability to compel its companies to follow its directions, it has the opportunity afforded by the presence of Chinese AI-enabled products and services in our digital ecosystems, and it has demonstrated malign intent towards the democracies.

But this is a more subtle and complex problem than deciding whether to ban Chinese companies from participating in 5G networks. Telecommunications networks are the nervous systems that run down the spine of our digital ecosystems; they’re strategic points of vulnerability for all digital technologies. Protecting them from foreign intelligence agencies is a no-brainer and worth the economic and political costs. And those costs are bounded because 5G is a small group of easily identifiable technologies.

In contrast, AI is a constellation of technologies and techniques embedded in thousands of applications, products and services. So the task is to identify where on the spectrum between national-security threat and moral panic each of these products sits, and then pick the fights that really matter.

A prohibition on all Chinese AI-enabled technology would be extremely costly and disruptive. Many businesses and researchers in democracies want to continue collaborating on Chinese AI-enabled products because it helps them to innovate, build better products, offer cheaper services and publish scientific breakthroughs. The policy goal is to take prudent steps to protect our digital ecosystems, not to economically decouple from China.

What’s needed is a three-step framework to identify, triage and manage the riskiest products and services. The intent is similar to that proposed in the recently introduced draft US RESTRICT Act, which seeks to identify and mitigate foreign threats to information and communications technology products and services—although the focus here is on teasing out the most serious threats.

Step 1: Audit. Identify the AI systems whose purpose and functionality concern us most. What’s the potential scale of our exposure to this product or service? How critical is this system to essential services, public health and safety, democratic processes, open markets, freedom of speech and the rule of law? What are the levels of dependency and redundancy should it be compromised or unavailable?

Step 2: Red team. Anyone can identify the risk of embedding many PRC-made technologies into sensitive locations, such as government infrastructure, but, in other cases, the level of risk will be unclear. For those instances, you need to set a thief to catch a thief. What could a team of specialists do if they had privileged access to a candidate system identified in Step 1—people with experience in intelligence operations, cybersecurity and perhaps military planning, combined with relevant technical subject-matter experts? This is the real-world test because all intelligence operations cost time and money, and some points of presence in a target ecosystem offer more scalable and effective opportunities than others. PRC-made cameras and drones in sensitive locations are a legitimate concern, but crippling supply chains through accessing ship-to-shore cranes would be devastating.

We know that TikTok data can be accessed by PRC agencies and reportedly also reveal a user’s location, so it’s obvious that military and government officials shouldn’t use the app. Journalists should also think carefully about this, too. Beyond that, the merits of a general ban on technical security grounds are a bit murky. Can our red team use the app to jump onto connected mobiles and ICT systems to plant spying malware? What system mitigations could stop them getting access to data on connected systems? If the team revealed serious vulnerabilities that can’t be mitigated, a general ban might be appropriate.

Step 3: Regulate. Decide what to do about a system identified as ‘high risk’. Treatment measures might include prohibiting Chinese AI-enabled technology in some parts of the network, a ban on government procurement or use, or a general prohibition. Short of that, governments could insist on measures to mitigate the identified risk or dilute the risk through redundancy arrangements. And, in many cases, public education efforts along the lines of the new UK National Protective Security Authority may be an appropriate alternative to regulation.

Democracies need to think harder about Chinese AI-enabled technology in our digital ecosystems. But we shouldn’t overreact: our approach to regulation should be anxious but selective.

Almost exactly 66 years ago, 22 pre-eminent scientists from 10 countries, including the United States and the Soviet Union, gathered in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, to identify the dangers that nuclear weapons posed and devise peaceful ways of resolving conflicts among countries. With that, the international organisation known as the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, or the Pugwash Movement, was born. Though the world is hardly free of nuclear weapons, the movement’s efforts to advance disarmament were powerful enough to win it the Nobel Peace Prize in 1995.

Today, the world needs a new Pugwash movement, this time focused on artificial intelligence. Unlike nuclear weapons, AI holds as much promise as peril, and its destructive capacity is still more theoretical than real. Still, both technologies pose existential risks to humanity. Leading scientists, technologists, philosophers, ethicists and humanitarians from every continent must therefore come together to secure broad agreement on a framework for governing AI that can win support at the local, national and global levels.

Unlike the original Pugwash Movement, the AI version would not have to devise a framework from scratch. Scores of initiatives to govern and guide AI development and applications are already underway. Examples include the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights in the United States, the Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI in the European Union, the OECD’s AI Principles and UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence.

Instead, the new Pugwash movement would focus largely on connecting relevant actors, aligning on necessary measures and ensuring that they are implemented broadly. Institutions will be vital to this effort. But what kind of institutions are needed and can realistically be established or empowered to meet the AI challenge quickly?

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has called for ‘networked multilateralism’, in which the UN, ‘international financial institutions, regional organisations, trading blocs and others’—including many nongovernmental entities—‘work together more closely and more effectively’. But to be effective, such multi-stakeholder networks would have to be designed to serve specific functions.

A paper released this month by a group of leading AI scholars and experts from universities and tech companies identifies four such functions with regard to AI: spreading beneficial technology, harmonising regulation, ensuring safe development and use, and managing geopolitical risks.

Understandably, many consider ‘ensuring safe development and use’ to be the top priority. So, efforts are underway to develop an institution that will identify and monitor actual and potential harms arising from AI applications, much as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change monitors the existential risk of climate change. In fact, the Global AI Observatory, recently proposed by the Artificial Intelligence and Equality Initiative, would be explicitly modelled on the IPCC, which is essentially a network of networks that works very well for accumulating knowledge from many different sources.

Cumulation networks—from the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s incident reporting system to Wikipedia—have a central authoritative hub that can pull together information and analysis from many different types of institutions, some of which are already networked. But such a hub can’t take swift action based on the information it gathers. To govern AI, a hierarchical multilateral institution with the power to make and implement decisions—such as a functioning UN Security Council—is still needed.

As for the function of spreading beneficial technology (which is just as important for most people as preventing harm), a combined innovation–collaboration network is likely to work best. Innovation networks typically include many far-flung nodes—to ensure access to as many sources of new ideas and practices as possible—and a limited number of hubs focused on transforming ideas into action, collaborating on best practices and preventing exploitation. The hubs could be centred in specific regions or perhaps tied to specific UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Harmonising regulation—including experimenting with different types of regulation—will require a broader, looser and maximally inclusive structure. AI technologies are simply too broad and too fast-moving for one or even several centralised regulatory authorities to have any chance of channelling and guiding them alone. Instead, we propose a widely distributed multi-hub network that supports what we call ‘digital co-governance’.

Our model is based on the distributed architecture and co-governance system that are widely credited with maintaining the stability and resilience of the internet. Decades ago, technology researchers, supported by the US government and early internet businesses, created several institutions in a loosely coordinated constellation, each with its own functional responsibilities.

The Internet Society promotes an open, globally connected internet. The World Wide Web Consortium develops web standards. The Internet Governance Forum brings stakeholders together to discuss relevant policy issues. And the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) coordinates and safeguards the internet’s unique identifiers.

The key to these institutions’ success is that they are operated through distributed peer-to-peer, self-governing networks that bring together a wide range of stakeholders to co-design norms, rules and implementation guidelines. ICANN, for example, has dozens of self-organised networks dealing with the Domain Name System—crucial to enable users to navigate the internet—and coordinates other self-governing networks, such as the five regional institutions that manage the allocation of IP addresses for the world.

These institutions are capable of handling a wide range of policy questions, from the technical to the political. When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the Ukrainian authorities pressured ICANN to remove .ru from the Domain Name System’s master directory, known as the root zone, which is managed by 12 institutions across four countries, coordinated but not controlled by ICANN. Ultimately, the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority declined the request.

A Pugwash-like conference on AI would have no shortage of proposals to consider, or governmental, academic, corporate and civic partners to engage. The original Pugwash participants were responding to a call from intellectual giants like the philosopher Bertrand Russell and the physicist Albert Einstein. Who will step up today?

As Australia becomes the latest country to ban the Chinese-owned content platform TikTok from government devices, it would be a mistake to limit the public policy debate to traditional state-on-state espionage or major power rivalry.

Such platforms and the advent of the eerily relatable artificial intelligence tool ChatGPT are society-changing technologies that cannot be dismissed as benign or treated as a public good closed to any regulatory or governance process.

ChatGPT and GPT-4, released in recent months by the US organisation OpenAI, create a sense of intimacy and identification with the user that, as the technology improves, will enable them to affect our thinking in ways that are orders of magnitude greater than today’s social media.

The name ‘chatbots’ hardly does them justice. ‘Synthetic relationships’ is the description used by some concerned technology commentators.

TikTok, meanwhile, is not just another app. It is influenced by an authoritarian political system while, in turn, having enormous influence in shaping public opinion by controlling what users see and hear.

Although chatbots and TikTok are distinct issues, they converge on one thorny question: how should liberal-democratic governments involve themselves in the use of technology so that citizens are protected from information manipulation—and hence influence over our beliefs—on an unprecedented scale?

The answer is that it’s time for democratic governments to step in more heavily to protect our citizens, institutions and way of life. We cannot leave a handful of tech titans and authoritarian regimes to rule the space unchallenged, as AI has the potential not only to be a source of information, but to establish a monopoly on truth that goes beyond human knowledge and becomes a new form of faith.

To date, Western governments have largely leaned towards a hands-off approach. Born partly out of the ideological struggles of the Cold War, we believed that governments should stay out of the way lest they stifle innovation.

Meanwhile, authoritarian regimes in China, Russia and elsewhere have grasped the value of technology as something they can control and weaponise, including to win information battles as part of broader political warfare. As Russian President Vladimir Putin said of AI in 2017: ‘Whoever becomes the leader in this sphere will become the ruler of the world.’

We would never want governments to control the information sphere as happens under authoritarian systems. But the philosophy of relying on the free market no longer works when the market is distorted by the Chinese Communist Party, the Putin regime and others who have collapsed the public–private distinction and are interfering heavily in what we once hoped might be a free marketplace of ideas.

The combined lesson of chatbots and TikTok is that we face a future challenge of technology that can establish a convincing sense of intimacy comparable to a companion, friend or mentor, but that is controlled by authoritarian regimes. Although AI and social media are distinct, the content users receive would ultimately be dictated by architecture built by humans beholden to an authoritarian system.

Let’s say the chatbot spends a few weeks establishing a relationship with you. Then it casually drops into a conversation that a particular candidate in a coming election has a policy platform remarkably in tune with your political beliefs. That might feel creepy, wherever the chatbot comes from.

Now let’s say it was built not by an independent outfit such as OpenAI, but by a Beijing- or Moscow-backed start-up. It notices you’ve been reading about Xinjiang and helpfully volunteers that it has reviewed social media posts from Uyghur people and concluded most of them actually feel safe and content.

Or you’ve been looking at news about Ukraine, so the chatbot lets you know that many experts reckon NATO made a mistake in expanding eastwards after 1991, and therefore you can hardly blame Moscow for feeling threatened. So really there are faults on both sides and a middle-ground peace settlement is needed.

The power of chatbots demonstrates that the debate over TikTok is the tip of the iceberg. We are going to face an accelerating proliferation of questions about how we respond to the development of AI-driven technology. The pace of change will be disorientating for many people, to the point that governments find it too difficult to engage voters. That would be a terrible failure.

Some 1,300 experts, even Elon Musk, are sufficiently troubled that they have called for a six-month pause on developing AI systems more powerful than GPT-4. And the Australian Signals Directorate just last week recognised the need to balance adoption of new technology with governance and issued a set of ‘ethical principles’ to manage its use of AI.

This is a welcome step, but leaves open the question of what are we doing to manage Beijing’s or Moscow’s use of AI?

We need an exhaustive political and public debate about how we regulate such technologies. That is why ASPI has this week hosted the Sydney Dialogue, a global forum to discuss the benefits and challenges of critical technologies.

One starting point would be to treat applications that shape public opinion in the same way as media providers, involving restrictions if they cannot demonstrate independence from government. This would separate the likes of the ABC and BBC—funded by government but with editorial or content independence—from government-controlled technologies that could exercise malign influence. This would also maintain a country-agnostic regulatory approach.

We will need to wade through many moral conundrums and find solutions we can realistically implement. Part of it will be national regulation; part will be international agreements on rules and norms. We don’t want to stifle innovation, nor can we leave our citizens to fend for themselves in what will be, at best, a chaotic and, at worst, a polluted and manipulated information environment.

Government involvement is not interference. A tech future based on anarchy with no rules will itself be ruled by authoritarian regimes.

ASPI’s Sydney Dialogue is already on its way to becoming the world’s premier policy summit on critical, emerging, cyber and space technologies. When we wanted to build this dialogue four years ago, not all stakeholders saw the global gap we were trying to fill, and it almost felt a bit before its time.

Today, that gap is glaringly obvious and revealed daily in the news as we watch technology race ahead. Few today would argue against its value for Australia, the Indo-Pacific region and, in light of Russia’s war on Ukraine, globally.

Critical technologies are, of course, at the centre of strategic competition between states. Should society care? Absolutely, because those very technologies are already changing our daily lives. Knowing who is building and controlling the technologies we are using every day is vital. The security, prosperity, political stability and social harmony of nations—and coalitions of nations—will all depend on their ability to harness the promise and create clear parameters to guide the safe and responsible use of critical technologies.

Quantum computing, for example, offers the potential to solve in seconds complex problems that would take the fastest supercomputer thousands of years. Such a breakthrough could render existing security measures obsolete and shift social and geopolitical relations overnight. Artificial intelligence, meanwhile, has the promise of freeing us from both routine and complicated tasks, allowing individuals and organisations to focus on higher-level strategic and creative endeavours. But it also involves the risk of the AI not understanding important nuances in global geopolitics and human rights, for example, which can lead to mis- and disinformation. We are already seeing how AI can be weaponised to pollute our information environment with dangerous propaganda and deepfakes.

Beyond the technologies themselves, there are transformational shifts in how innovation is taking place and who is doing the innovating. During the Cold War, the research and development of critical technologies—particularly those relevant to security—were driven largely by huge government-funded programs in government-controlled facilities. Of course, only a small number of governments had the resources to generate cutting-edge technologies. Today, leading- and bleeding-edge technologies are emerging out of commercial R&D programs, which means they are available to a wider range of strategic players, large and small. This complicates national efforts; technology companies based in one country can, and in many cases do, work for the governments of other countries, even when the strategic goals of the two countries are misaligned.

Innovation is also increasingly achieving a bootstrapping effect. As former Google CEO Eric Schmidt has written of artificial intelligence: ‘Faster airplanes did not help build faster airplanes, but faster computers will help build faster computers.’

Regulatory and policy responses are struggling to keep up. No single sector, be it government, the tech industry or civil society, has all the answers. But democracies risk falling further behind as authoritarian regimes, without the same governance principles or accountability and transparency mechanisms, and with military–civil fusion, have surged ahead to the detriment of democratic ideals, social harmony and international standards. While we thought the internet and social media were uncontrollable, they harnessed new capability to wield greater power. With yet another tech revolution imminent, we cannot afford to be slow and passive again. We have to learn from the past or it will be a case of third strike.

That’s why the Sydney Dialogue was established in 2021. We need forums where the world’s leading thinkers and decision-makers—from government, industry, academia and civil society—can meet and exchange ideas and strategies, deepen cooperation and form new partnerships. While we’re attuned to the threats and challenges, we’ve very deliberately sought contributions from actors who have a positive and proactive vision for technology that upholds fundamental values such as human rights, openness and sovereignty.

Those players who share this vision must be the ones who shape the rules of the road. We don’t want to see a lawless space, and we certainly don’t want to see a technology ecosystem shaped by actors who are happy to use technology to spread disinformation, enable coercion or trample fundamental individual rights.

At the heart of the Sydney Dialogue is a discussion about how to harness the opportunities and mitigate the risks of technology, which will include the benefits of international collaboration, ways to protect sovereignty and build resilience, policies to foster investment and innovation, the next game-changers in technology, geopolitics and why technology lies at the heart of competition, and how we work together on governance and public policy.

Key technologies include AI, 5G/6G, robotics, biotech, nanotech, quantum, space, our information environment and of course cyber. The conversation brings in economies, climate change and energy, our societies, foreign policy, national security, defence capability, intelligence and ethics, and many other topics.

The goal of the Sydney Dialogue is to make a lasting contribution to ensuring these technologies grow in the right way—making us more prosperous, more equal, wiser, freer, safer and more secure. We aim to give the Indo-Pacific a new platform and a greater voice in global debates, while helping to build cooperation and global partnerships between government, industry and civil society, and between partners and allies.

Originally published 31 March 2022.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the poorer than expected performance of the Russian army have prompted fierce debate among military commentators on why Russia’s much-vaunted military reforms of the past decade—particularly the integration of artificial intelligence technologies that were supposed to enhance Russia’s joint operations capability—seem to have been unsuccessful.

So far, Russia’s deployment in Ukraine has been a demonstration of some of the limitations and vulnerabilities of AI-enabled systems. It has also exposed some longer-term strategic weaknesses in Russia’s development of AI for military and economic purposes.

Russia’s use of AI-enabled technologies in the invasion reportedly includes disinformation operations, deep fakes and open-source intelligence gathering. But information operations are not the sum total of Russia’s AI capabilities. AI is embedded across the military spectrum, from information management, training, logistics, maintenance and manufacturing, to early warning and air-defence systems.

Since at least 2014, Russia has deployed multiple aerial, ground and maritime uncrewed systems and robotic platforms, electronic warfare systems, and new and experimental weapons in both Syria and Ukraine.

The AI elements in these systems include image recognition and image stitching in Orion combat drones, radio signal recognition in Pantsir-S1 anti-aircraft systems, AI-enabled situational understanding and jamming capability in the Bylina electronic warfare system, and navigation support in the Kamaz truck. So-called kamikaze drones (developed by the Kalashnikov Group, the maker of the famous assault weapon) appear to use a mix of manual and automated target acquisition.

One of the earliest images that circulated online in the current conflict was of a Russian Pantsir-S1 stuck in the mud in a field in southern Ukraine. The Pantsir is a component of the early warning and air-defence system that features both short-range surface-to-air missiles and 30-millimetre automatic cannon.

If we look under the hood at the purported AI technologies of the Pantsir, Russian state media Izvestia reported two years ago that it

is capable of detecting, classifying and firing at air targets without the participation of an operator. The developed algorithms instantly determine the importance of objects and arrange the order of their destruction depending on the danger they represent …

Its software takes into account the tactical situation, the location of targets, their degree of danger, and other parameters and selects the optimal tactics for repelling a raid.

It’s wise to be wary of Russian claims of full autonomy, both because the capacities of AI-enabled systems tend to be overblown and because deliberately fabricated information is a component of Russia’s approach to new-generation warfare.

There are reasons to be concerned about the individual systems and their AI components, but it’s important to consider Russia’s grander AI vision.

The Pantsir-S1 is just one node of an interconnected system that includes airborne radar systems, satellites and reconnaissance drones, and panoptic information-management systems.

Just as the West has been pursuing a vision of an interconnected battlefield in the form of a ‘joint all-domain command and control centre’ (JADC2) concept, Russia has its ‘national defence management centre’ (NDMC), which aims for the same. The goal is to build systems in which ‘data can move seamlessly between air, land, maritime, space, and cyber forces in real time’.

According to researchers at CNA, a US think tank, ‘NDMC was designed to receive information from the lowest military unit levels, and, following analysis and evaluation, feed the data directly to those at the strategic level.’ This defines the battlefield in multiple dimensions and makes shared situational understanding contingent on information from the edge of the battlespace.

There has been some speculation that poor-quality tyres or failure to account for local conditions indicate vulnerabilities in Russian forward planning. While these physical aspects are important, in a battlespace that’s dependent on information it’s also important to consider the extent of interoperability of systems, any bandwidth constraints, and the tendency in computer-assisted decision-making to equate a map with territory. Expanding a military’s capacity to use so-called real-time information requires analyst teams to interpret and leadership to prioritise the information.

The critical human element was hindered because Russia’s planning seems to have been tightly held within President Vladimir Putin’s inner circle (which does not include the army) until just before the invasion.

Putin said in 2017, ‘Whoever becomes the leader in this sphere [artificial intelligence] will become the ruler of the world.’ Since then, he has pushed the use of defence sector spending and defence acquisition to generate national economic growth and drive national technological innovation.

With few reasons to adhere to international norms on ethical AI development, including regulation of data harvesting, as well as a ready supply of programming talent, Russia could be perhaps seen as having some advantages in AI developments, and the ability to quickly deploy innovations into its asymmetric warfare programs.

However, the two directions in which the Kremlin is steering the Russian defence sector—increasing civilian and dual-use goods and import substitution—carry some distinct vulnerabilities for Russia. Despite pushes by Putin in recent years towards economic self-sufficiency, the interconnected nature of global trade means that there are key technology choke points that affect Russia’s AI development.

The main barrier to Moscow’s vision of AI supremacy is microchips. Russian media has claimed that NDMC’s information management runs on ‘Russian-made’ Elbrus microprocessors. However, Russia lacks the ability to produce these microchips. The production of Elbrus chips is outsourced to Taiwan, to the company TSMC, which has now suspended its production and export to Russia.

At a broader level, at least 1,300 Russian defence enterprises have shortages in human capital, particularly in process engineering, and the exodus of tech talent from Russia has been accelerated by the war. A range of Western sanctions in key technologies and commodities will hit the Russian economy hard, even if it tries to substitute with imports from China.

Some analysts have claimed that Russian underinvestment in technology modernisation has hampered the army’s ability to ‘see’ the battlefield, forcing it to rely on the brute force of tanks and artillery. For those Ukrainians now under siege in cities around the country, the apparent modernisation of Russia’s war apparatus will be perhaps a moot point as artillery rains down. But AI is a critical technology that will be increasingly important for both economic development and national defence. It’s important to understand both the way it is embedded in technologies and the international supply-chain interdependencies that are crucial for its development.

Using automated systems, such as those enabled with artificial intelligence, to assist with recruitment can create efficiencies, but the increasingly complex interplay of machines, ownership and control of data, contract performance and human factors makes the effects difficult to predict. While solutions may be found by integrating hiring technology with deep knowledge of organisational needs and culture and adapting skills standards, recruitment is only one part of the workforce crisis facing Australia’s defence organisation.

These issues should be front of mind in the transition of the Australian Defence Force recruiting contract from Manpower to Adecco in the context of shortfalls in recruitment. Issues of the contract with Manpower have not been canvassed in public, but there are, without doubt, commonalities with contracting in other countries, such as the UK, which also has faced myriad recruitment challenges.

Recruitment methods, of course, rely increasingly on data, analytics and algorithms, and globally there are efforts to push legacy personnel systems into the information age.

The UK Ministry of Defence has released an AI strategy that has as one pillar transforming the armed forces into an ‘AI ready’ organisation by addressing human talent.

The UK strategy comes after a long period of underperformance in recruiting. A parliamentary committee inquiry criticised both the British Army and the contractor, Capita. The army achieved only 60% of its targets in 2018–19 and identified issues in recruitment in future skills and capabilities, such as digital technology and cybersecurity.

The inquiry found that Capita had underestimated the complexity of defence recruiting and the specialist expertise needed. It concluded that Capita’s off-the shelf commercial solution was not fit for purpose, and noted that a bespoke application took longer to develop than anticipated.

An overly prescriptive contract containing 10,000 specifications negatively affected innovation in the recruitment process. The recruitment system was not owned by the British Army and was hosted on the contractor’s servers.

Problems clearly remain. The system went offline for six weeks this year after a possible hack. The information of 120 recruits was found on the dark web.

The UK issues will no doubt resonate with those familiar with Australia’s problems.

The ADF and the Department of Defence are both below their budgeted personnel numbers. Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles said last month that the recruitment issue must be dealt with urgently. He said the ADF was almost 3,000 people below its allocated force strength and the Department of Defence was more than 1,000 people below its budgeted size.

The contract between the ADF and the new contractor, Adecco, will likely reflect the revised defence intellectual property strategy that outlined a new regime for collaboration with industry.

The ownership of data and online systems by contractors creates dependencies that may limit the scope for employers to gain insights from that data and to innovate. The experience of the British Army is instructive. Despite multiple years of missed targets, the British Army didn’t amend the contract with Capita to secure the intellectual property for the online recruitment system that it had co-developed and co-funded.

In recruitment systems, there are good reasons to quarantine candidates’ files—which may contain the results of aptitude tests and other personal information—from other defence systems. But air-gapped data creates other points of vulnerability—the ADF confirmed in October that hackers had attacked an external service provider used by military personnel and public servants.

During Australia’s first Covid-19 shutdown, defence recruitment applications surged, rising 42% in 2020 according to the ABC. But converting interest into boots on the ground has proved difficult. Digitising the recruitment process seems to have also driven an increase in applications from ‘unsuitable’ candidates.

The ADF’s three services have each apparently insisted on tailoring standards—including medical, physical and psychological assessments—based on job roles and improving the speed of application. They essentially want more control over who is deemed ‘suitable’.

This potential change to suitability criteria will undoubtedly attract internal and external criticism about supposedly declining standards. The inquiry in the UK said found that the British Army wasn’t changing its entry standards but widening its entry criteria. The ADF has already adapted its recruitment process to assess the physical differences between men and women more fairly while also relaxing its grooming standards to adapt to social norms. And as different defence requirements emerge—cyber is a classic example—defence has had to adjust.

Addressing retention is also a key part of solving the workforce problem, as ASPI’s Marcus Hellyer argued recently. While some elements of the defence workforce model will always remain, a cookie-cutter model for the ‘right’ sailor, soldier or aviator is no longer organisationally beneficial.

Data might be able to help Defence determine why candidates fail at different points, and equally where management is failing. But that information will be limited if partial details have been shared between the contractor and Defence, and if senior management isn’t monitoring performance, as was the case in the UK.

Equally, recruitment methods need to be adapted to the needs of different groups. Evidence of those involved in recruitment of Indigenous candidates, for example, suggests that advancement often occurs in contexts where they have strong peer support. Indigenous candidates haven’t had high rates of recruitment, so machine-learning systems trained on historical data could reinforce the same exclusions. The same is true for other groups.

In various contexts, AI or advanced analytics are being proposed to deliver a range of benefits. These include increasing the ability of organisations to conduct background checks; assess candidates’ values, beliefs and attitudes; and suggest possible behavioural patterns in relation to job fit and performance. But these systems can lead to perverse outcomes and legal risks, and in some instances can look like 19th-century-style pseudo-science. Efforts to identify ‘trustworthiness’ and ‘criminality’ in people’s facial structures are modern-day phrenology, no matter how many data points are being processed and how sophisticated the algorithm.

As Defence’s data-management systems become increasingly ‘optimised’ in line with its data strategy, we should be mindful that optimisation may not mean control and that contract complexity may stymie innovation. These are big questions in themselves, but the question of whether these enhancements will help tailor a force structure to align with likely workforce limits is even bigger.

As Australia’s foreign and defence ministers and the US secretaries of state and defence prepare to meet for the annual AUSMIN consultations, ASPI has released a collection of essays exploring the policy context and recommending Australian priorities for the talks. This is the last of three edited extracts from the volume’s technology chapter, which proposes five key science and technology areas for greater US–Australia collaboration that carry significant national security and defence risks for both countries.

Removing adversaries’ safe havens: cyber capacity-building with vulnerable nations

While it’s often said that the best defence is a good offence, when you’re outgunned, having friends is better. Neighbours and potential allies who lack cybersecurity awareness and skills and manage their infrastructure accordingly, however, are vulnerable to manipulation and control by aggressive foreign adversaries. This can take the form of cyberattacks, in which sensitive data is exfiltrated or manipulated on their networks, leaving them open to covert influence or blackmail.

In some cases, such activities can be overt, like China’s commercial diplomacy, offering technology and infrastructure to nations unaware of the support commitments, the degree of dependency they incur or the extent to which their systems will remain accessible by a foreign power. Regardless, it’s difficult to trust and collaborate with even friendly nations who leak sensitive information, provide access vectors to adversaries or allow their infrastructure to be co-opted for attacks against others.

Before Russia’s illegal war in Ukraine, the technology sector worked closely with the Ukrainian government to patch and upgrade vulnerable systems. That preparatory work significantly reduced the efficacy of Russian cyberattacks and removed enough of the low-level attack vectors so that, when the war began and they were under pressure, Ukraine and its tech partners were able to focus on responding to the much smaller number of sophisticated attacks Russia had prepared in secret.

That strategy doesn’t scale to other nations during peacetime, since those services ordinarily come with a high price tag that nations mightn’t be prepared to pay. Also, going in and making changes ourselves can come across as arrogant or interfering, fomenting distrust from the nation and its allies, and also ensuring that we inherit the ongoing support burden on top of our own work. A far better strategy is to respectfully help them help themselves—jointly develop initiatives that increase their own capacity to secure and manage their infrastructure, and respond effectively to cyber incidents.

The idea of helping a foreign nation fix the kinds of vulnerabilities that we might have exploited for intelligence collection would once have been unthinkable to the intelligence community. However, now that there’s a degree of homogenisation in our respective technology stacks, the cost of finding a vulnerability that might also affect one’s own systems quickly becomes too high to risk keeping it secret. Defending one’s own networks is far more work than attacking someone else’s, so today cyber defence will almost always be prioritised over intelligence gain.

Ultimately, we all benefit from raising up our neighbours. We’re able to build trust between different nations diplomatically; we can build trade and information-exchange opportunities safely; we can share the cyber-incident response burden across a greater pool of cyber professionals; and, critically, we can focus our limited resources on high-impact cases by disrupting the cyberattack chain earlier in its life cycle, preventing adversaries from even reaching our networks.

Recommendation: AUSMIN should invest in capacity-building programs, including training and professionalisation of the cyber discipline, to improve other nations’ cyber resilience. This includes being prepared, on occasion, to sacrifice technical access to intelligence for the greater good.

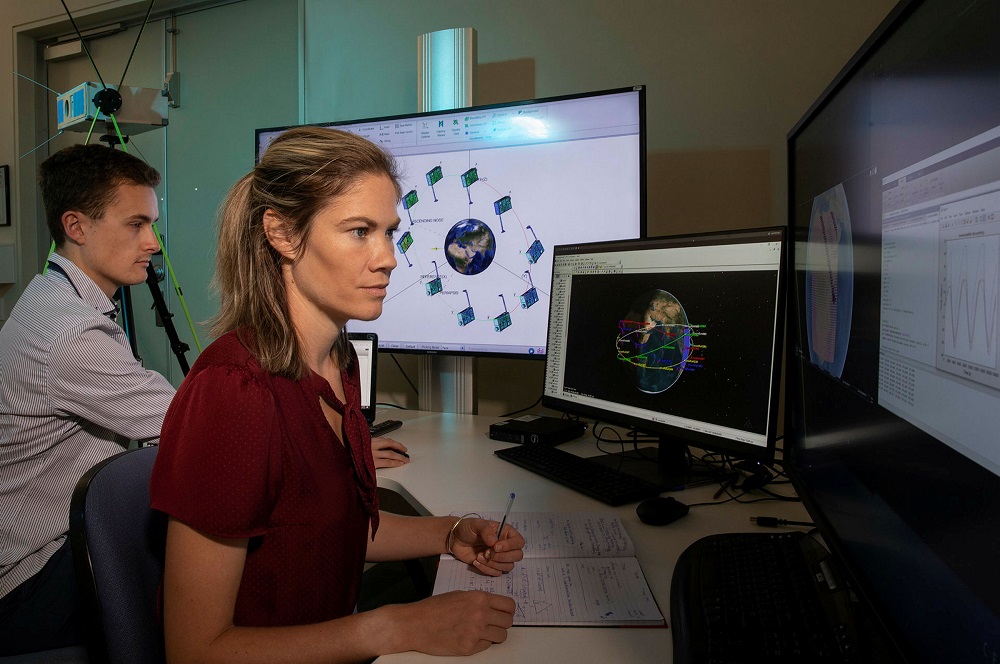

Seeing the bigger picture: data management for analytics, automation and AI

In recent years, artificial intelligence has been listed as a key priority for every major collaborative partnership Australia has signed up to, including AUKUS, the Quad, ASEAN and the Five Eyes. This is due to its enormous potential for being able to identify patterns, solve problems, provide insights and take actions at a speed and scale unmatched by people. However, underpinning all of its potential is the data that it’s based upon. An AI’s success or failure is inextricably linked to how it’s able to learn from data, to interpret it correctly, to make sound inferences and to then apply those inferences in ways that usefully apply in other contexts.

For example, for a good decision to be made, data should be accurate, timely, representative, relevant, trustworthy and appropriately sourced for the problem that the AI’s trying to solve. It should be structured or at least in understood formats, ideally adhering to standards, so it can be compared with or enriched with other data. It should also be assessed for biases so that either they can be mitigated or the AI users can be made aware of the boundaries and context of the answers that the AI will produce.

AI aside, a wealth of data is being generated every second from sensors on military platforms, but to gain the maximum impact from data to support military decision-making, it’s best enriched with contextualising information such as, say, environmental data, secret intelligence, commercial records, cyber data and so on. However, even efforts to collect together similar sensor data from across the army, navy and air force in the same region are extremely difficult, let alone sharing between countries and using different kinds of data.

To build, for example, a common picture of a battlefield during a conflict, we would also need consistent standards, data-processing platforms, manageable data volumes and, possibly the most difficult of all, policies for data and knowledge sharing between different countries, including how to address different sensitivities, equities and releasability.

Data management and accountability is a vastly underappreciated aspect of AI and, while the Five Eyes community has been working on this for some time, it remains one of the greatest challenges for collaboration. It will be critical in effectively monitoring a battlespace characterised by smart technologies such as AIs and drones and employing offensive cyber techniques.

Recommendation: AUSMIN should commit to developing standards for sharing battlefield data in a common picture, using existing Five Eyes programs as a foundation for streamlining processes.

Artificial intelligence is a general-purpose technology that is steadily becoming pervasive across global society. AI is now beginning to interest the world’s defence forces, but the military comes late to the game. Given this, defence forces globally are fundamentally uncertain about AI’s place in warfighting. Accordingly, there’s considerable experimentation in defence AI underway worldwide.

This process is being explored in a new series sponsored by the Defense AI Observatory at the Helmut Schmidt University/University of the Federal Armed Forces in Germany. Unlike other defence AI studies, the series is not focusing solely on technology but instead is looking more broadly across what the Australian Defence Force terms the ‘fundamental inputs to capability’. The first study examines Australian defence AI, and another 17 country studies have already been commissioned.

The ADF conceives of AI as mainly being used in human–machine teams to improve efficiency, increase combat power and achieve decision superiority, while lowering the risk to personnel. For a middle power, Australia is following a fairly active AI development program with a well-defined innovation pathway and numerous experimentation projects underway.

There is also a reasonable level of force structure ambition. The latest major equipment acquisition plan, covering the next 10 to 20 years, sets out six defence AI-relevant projects, one navy, one army, three air force and one in the information and cyber domain. Even in this decade, the AI-related projects are quite substantial; they include teaming air vehicles (with an estimated cost of $9.1 billion), an integrated undersea surveillance system ($6.2 billion), a joint air battle management system ($2.3 billion) and a distributed ground station ($1.5 billion).

Associated with this investment is a high expectation that Australian AI companies will have considerable involvement in the projects. Indeed, the government recently added AI to its set of priorities for sovereign industrial capability. The Australian defence AI sector, though, consists mainly of small and medium-sized companies that individually lack the scale to undertake major equipment projects and would need to partner with large prime contractors to achieve the requisite industrial heft.

There are also wider national concerns about whether Australia will have a large enough AI workforce over the next decade to handle commercial demands, even without Defence drawing people away for its requirements. Both factors suggest Defence could end up buying its AI offshore and rely principally on long-term foreign support, as it does for many other major equipment projects.

An alternative might be funding collaborative AI developments with the US. A harbinger of this may be the Royal Australian Navy’s new experimentation program involving a recently decommissioned patrol boat being fitted with Austal-developed autonomous vessel technology featuring AI. Austal is simultaneously involved in a much larger US Navy program fitting its system to one of the company’s expeditionary fast transport ships, USNS Apalachicola, currently being built. In this case, Austal is an Australian company with a large US footprint and so can work collaboratively in both countries. The RAN, simply because of economies of scale, is probably more likely to adopt the US Navy variant rather than a uniquely Australian version.

The outlier to this acquisition strategy might be the Boeing Australia Ghost Bat program that could see AI-enabled, ‘loyal wingman’ uncrewed air vehicles in limited ADF service in 2024–25, before the US. The US Air Force is running several experimentation programs aiming to develop suitable technologies, some of which also involve the Boeing parent company. There’s a high likelihood of cross-fertilisation between the Australian and US programs. This raises the tantalising possibility of a two-nation support system of a scale that would allow the Australian companies involved to grow to a size suitable for long-term sustainment of the relevant ADF AI capabilities. This possibility might be a one-off, however, as there seem to be no other significant Australian defence AI programs.

Australia collaborating with the US on AI or buying US AI products can ensure interoperability. But in seeking such an objective there’s always a tension between each Australian service being interoperable with its US counterpart or instead across the ADF. This tension is likely to remain as AI enters service, especially given its demands for task-related big data.

Interoperability and domestic industry support are traditionally important issues, but they may need to be counterbalanced by emerging geostrategic uncertainties and ADF capability considerations. Australia is worried about the possibility of conflict in the Indo-Pacific region given Chinese assertiveness coupled with the example of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. To offset the numerically large military forces of the more bellicose Indo-Pacific states, some advocate developing a higher quality, technologically superior ADF that can help deter regional adventurism.

In being a general-purpose technology, AI can potentially provide a boost across the whole ADF, not just one or two elements within it. But such a vision is not what is being pursued. Defence’s current AI plans will most likely lead to evolutionary improvements not revolutionary changes. AI is envisaged as being used to either enhance, augment or replace existing capability; this approach means the future ADF will do things better, but it won’t necessarily be able to do better things.

A revolution in Australian military affairs seems unlikely under current schemes. For that, defence AI would need to be reconceptualised as a disruptive technology rather than a sustaining innovation. Embracing disruptive innovation would be intellectually demanding and, in suggesting the adoption of unproven force structures, could involve taking strategic risks. These are reasonable concerns that would need careful management.

Against such worries though, China looms large. The strategically intelligent choice for the ADF might be embracing disruptive AI.

Most technological advances spark incremental progress. And then a few come along that are truly game-changing.

AI is one of those truly transformative technologies. It’s set to revolutionise our lives and workplaces at rapid speed in the coming decade. It will potentially reshape almost every job, industry and life. It’s already being deployed across a wide array of Australian industries and sectors.

In the legal profession, AI is now being used to scan and prepare legal briefs. There’s also a growing array of analytics applications being used to save people time and resources.

In medicine and health care, the potential of AI is enormous, but yet to be truly realised. Many parts of health care stand to benefit from a data-driven approach, including image analysis to improve the detection and diagnosis of disease. Analysis of patient data has helped to predict and prevent falls among at-risk patients. However, these game-changing possibilities need more work and more investment to reach their full life-saving potential.

A uniquely Australian example can be found in Kakadu National Park. Indigenous owners are working with researchers to support ecosystem resilience through a combination of Indigenous knowledge, technology and AI. Under the direction of Indigenous rangers, drone footage collects data over areas of the national park that are difficult to access. AI is used to scan hours of video footage to identify para grass—an introduced fodder crop that’s displacing the native grasses, which are a key habitat for magpie geese. Strong numbers of magpie geese indicate that the country is healthy. Adaptive management has already seen the population in one wetland increase from 50 to 1,800 birds.

So why should Australia invest in AI R&D? If we want to secure the economic opportunities that will flow from AI, and shape those frontier technologies as they evolve, we must invest in a specialised, skilled workforce and advances in key technologies. If we don’t, we’ll be left behind—and our children and grandchildren will miss out on vast opportunities.

Australia’s Artificial intelligence roadmap cites three pivotal areas in which AI has the potential to shape our nation: natural resources and the environment; health, ageing and disability; and cities, towns and infrastructure. Those diverse fields highlight the potential breadth of AI applications in widely divergent aspects of our lives.

Other countries are investing, and investing big.

The biggest players in the AI game are the US and China.

The American National AI Initiative was unveiled in 2019. It drives the safe development, testing and deployment of AI technologies. The strategy recognises the importance of international collaboration, while striving to put the US at the front of global AI research. The US government’s investment in AI projects amounted to around US$5 billion in 2020. In 2021, the National Artificial Intelligence Initiative Office was launched to play a coordinating role for all AI research and policymaking across academia, government and industry.

China’s strategy, announced in 2017, aims to make China an AI leader by 2030. It has a key focus on technologies such as unpiloted aerial vehicles and voice and image recognition. While exact government funding amounts aren’t known, it’s clear that China is significantly upping its game in research activity, with very steep growth in publications on AI.

The Canadian government announced a national AI plan in 2017, investing C$125 million ($137 million) to support the Pan-Canadian AI Strategy. The strategy sets ambitious goals to attract and retain world-class AI researchers, nurture a collaborative AI ecosystem, support national AI initiatives, and contextualise AI work in its ethical and societal implications.

In 2018, the UK pumped nearly £1 billion ($1.87 billion) into AI research. It released its National AI Strategy in September 2021—a ‘10-year plan to make Britain a global AI superpower’.

In South Korea, the government allocated ₩1.7 trillion ($1.1 billion) in 2020 for data, networks and AI under its National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence. The strategy includes nine plans to drive advancements in the AI ecosystem, AI use and people-centred AI.

Singapore released its National AI Strategy in 2019. Its goal is to propel ‘Singapore as a leader in developing and deploying scalable, impactful AI solutions, in key sectors of high value and relevance to our citizens and businesses’. The Singaporean government has supported the strategy with funding totalling S$680 million ($695 million). The money will support projects in fundamental AI research, translational research and industry–research collaborations.

India is a very strong player, too. Its government released an AI strategy in 2018, identifying areas of focus in agriculture, health and education. This was backed by ₹7,000 crore ($1.3 billion). The Indian government is also working on its national program for AI, with a goal of ‘making India the global leader in AI, ensuring responsible and transformational AI for all’.

In the Australian context, the potential uses of AI to create safer and more interesting jobs and take on tasks that are either dangerous or repetitious are almost limitless. And the technology itself is even evolving our legal concepts.

In a landmark judgement in August 2021, Australia’s Federal Court ruled that an AI can be named as an inventor in a patent application—a decision that challenges the prevailing thought that AI systems can’t be truly creative.

As the world strives to deepen AI capabilities, diversity must be a critical policy consideration. AI has the power to radically transform our society, and we need to think constantly and simultaneously about the ethics and social implications as we develop the research. We need the best minds, of all genders, focused on this task. At the moment, only 22% of AI researchers are women. Given the huge ethical and societal implications of AI research and its applications, we need to ensure a diversity of brainpower, perspectives and experience to ensure optimal outcomes for our societies.

Diversity of thought also comes from including and incorporating other world views and cultural perspectives into AI research. Indigenous knowledge systems contain a wealth of experience, particularly to understand and live sustainably within our environment. Including Indigenous knowledge to inform AI research will lead to better, more holistic and more inclusive AI.

The CSIRO and Data61 forecast that AI benefits will be worth $22.17 trillion to the global economy by 2030. They predict that Australia could boost its economy by $315 billion by 2028 from digital technologies including AI. The CSIRO says that, in the next decade, by deepening our use of digital technologies, we could snare a slice of $30–50 billion in future Asia–Pacific markets for healthcare innovations, prevent up to 1,100 road deaths a year, and boost the farm-gate value of agriculture by $20 billion.

It will be a race to secure the benefits AI has to offer societies and nations. Countries around the globe are setting forward-looking strategies, with big ambitions, and backing them with significant funding. Australia needs to be in the race and to invest—at scale, and ensuring broad inclusion—in AI R&D. It’s a powerful investment in securing our future prosperity.

This article is an extract from a new report, Artificial intelligence: your questions answered, produced by ASPI in conjunction with the Australian Institute for Machine Learning at the University of Adelaide.

Correction (16 January 2023): An earlier version of this article misstated the Australian court that ruled that an AI system can be named an inventor in a patent application. It was the Federal Court, not the High Court. In April 2022—shortly after this article was originally published—that decision was overturned on appeal by the Full Court of the Federal Court. Currently in Australia an AI system cannot be named as an inventor in a patent application.