Nothing Found

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria

Dozens of countries around the world, from the United States to India, will hold or have already held elections in 2024. While this may seem like a banner year for democracy, these elections are taking place against a backdrop of global economic instability, geopolitical shifts and intensifying climate change, leading to widespread uncertainty.

Underpinning all this uncertainty is the rapid emergence of powerful new technologies, some of which are already reshaping markets and recalibrating global power dynamics. While they have the potential to solve global problems, they could also disrupt economies, endanger civil liberties, and undermine democratic governance. As Thierry Breton, the European Union’s commissioner for the internal market, has observed, ‘We have entered a global race in which the mastery of technologies is central’ to navigating the ‘new geopolitical order.’

To be sure, technological disruption is not a new phenomenon. What sets today’s emerging technologies apart is that they have reached a point where even their creators struggle to understand them.

Consider, for example, generative artificial intelligence. The precise mechanisms by which large language models like Google’s Gemini (formerly known as Bard) and OpenAI’s ChatGPT generate responses to user prompts are still not fully understood, even by their own developers.

What we do know is that AI and other rapidly advancing technologies, such as quantum computing, biotechnology, neurotechnology, and climate-intervention tech, are growing increasingly powerful and influential by the day. Despite the scandals and the political and regulatory backlash of the past few years, Big Tech firms are still among the world’s largest companies and continue to shape our lives in myriad ways, for better or worse.

Moreover, over the past 20 years, a handful of tech giants have invested heavily in development and acquisitions, amassing wealth and talent that empowers them to capture new markets before potential competitors emerge. Such concentration of innovation power enables these few players to maintain their market dominance – and to call the shots on how their technologies are developed and used worldwide. Regulators have scrambled to enact societal safeguards for increasingly powerful, complex technologies, and the public-private knowledge gap is growing.

For example, in addition to developing vaccines and early detection systems to trace the spread of viruses, bioengineers are developing new tools to engineer cells, organisms, and ecosystems, leading to new medicines, crops, and materials. Neuralink is working on trials with chip implants in the bodies of disabled people, and on enhancing the speed at which humans communicate with systems through direct brain-computer interaction. Meanwhile, quantum engineers are developing supercomputers that could potentially break existing encryption systems crucial for cybersecurity and privacy. Then there are the climate technologists who are increasingly open to radical options for curbing global warming, despite a dearth of real-world research into the side effects of global interventions like solar radiation management.

While these developments hold great promise, applying them recklessly could lead to irreversible harm. The destabilising effect of unregulated social media on political systems over the past decade is a prime example. Likewise, absent appropriate safeguards, the biotech breakthroughs we welcome today could unleash new pandemics tomorrow, whether from accidental lab leaks or deliberate weaponization.

Regardless of whether one is excited by the possibilities of technological innovation or concerned about potential risks, the unique characteristics, corporate power, and global scale of these technologies require guardrails and oversight. These companies’ immense power and global reach, together with the potential for misuse and unintended consequences, underscore the importance of ensuring that these powerful systems are used responsibly and in ways that benefit society.

Here, governments face a seemingly impossible task: they must oversee systems that are not fully understood by their creators while also trying to anticipate future breakthroughs. To navigate this dilemma, policymakers must deepen their understanding of how these technologies function, as well as the interplay between them.

To this end, regulators must have access to independent information. As capital, data, and knowledge become increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few corporations, it is crucial to ensure that decision-makers are able to access policy-oriented expertise that enables them to develop fact-based policies that serve the public interest. Democratic leaders need policy-oriented expertise about emerging technology – not lobbyists’ framings.

Having adopted a series of important laws like the AI Act over the past few years, the EU is uniquely positioned to govern emerging technologies on the basis of solid rule of law, rather than in service of corporate profits. But first, European policymakers must keep up with the latest technological advances. It is time for EU decision-makers to get ahead of the next curve. They must educate themselves on what exactly is happening at the cutting edge. Waiting until new technologies are introduced to the market is waiting too long.

Governments must learn from past challenges and actively steer technological innovation, prioritising democratic principles and positive social impact over industry profits. As the global order comes under increasing strain, political leaders must look beyond the ballot box and focus on mitigating the long-term risks posed by emerging technologies.

In Poznan, 325 kilometers east of Warsaw, a team of tech researchers, engineers, and child caregivers are working on a small revolution. Their joint project, ‘Insension’, uses facial recognition powered by artificial intelligence to help children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities interact with others and with their surroundings, becoming more connected with the world. It is a testament to the power of this quickly advancing technology.

Thousands of kilometers away, in the streets of Beijing, AI-powered facial recognition is used by government officials to track citizens’ daily movements and keep the entire population under close surveillance. It is the same technology, but the result is fundamentally different. These two examples encapsulate the broader AI challenge: the underlying technology is neither good nor bad in itself; everything depends on how it is used.

AI’s essentially dual nature informed how we chose to design the European Artificial Intelligence Act, a regulation focused on the uses of AI, rather than on the technology itself. Our approach boils down to a simple principle: the riskier the AI, the stronger the obligations for those who develop it.

AI already enables numerous harmless functions that we perform every day—from unlocking our phones to recommending songs based on our preferences. We simply do not need to regulate all these uses. But AI also increasingly plays a role at decisive moments in one’s life. When a bank screens someone to determine if she qualifies for a mortgage, it isn’t just about a loan; it is about putting a roof over her head and allowing her to build wealth and pursue financial security. The same is true when employers use emotion-recognition software as an add-on to their recruitment process, or when AI is used to detect illnesses in brain images. The latter is not just a routine medical check; it is literally a matter of life or death.

In these kinds of cases, the new regulation imposes significant obligations on AI developers. They must comply with a range of requirements—from running risk assessments to ensuring technical robustness, human oversight, and cybersecurity—before releasing their systems on the market. Moreover, the AI Act bans all uses that clearly go against our most fundamental values. For example, AI may not be used for social scoring or subliminal techniques to manipulate vulnerable populations, such as children.

Though some will argue that this high-level control deters innovation, in Europe we see it differently. For starters, time-blind rules provide the certainty and confidence that tech innovators need to develop new products. But more to the point, AI will not reach its immense positive potential unless end-users trust it. Here, even more than in many other fields, trust serves as an engine of innovation. As regulators, we can create the conditions for the technology to flourish by upholding our duty to ensure safety and public trust.

Far from challenging Europe’s risk-based approach, the recent boom of general-purpose AI (GPAI) models like ChatGPT has made it only more relevant. While these tools help scammers around the world produce alarmingly credible phishing emails, the same models also could be used to detect AI-generated content. In the space of just a few months, GPAI models have taken the technology to a new level in terms of the opportunities it offers, and the risks it has introduced.

Of course, one of the most daunting risks is that we may not always be able to distinguish what is fake from what is real. GPAI-generated deepfakes are already causing scandals and hitting the headlines. In late January, fake pornographic images of the global pop icon Taylor Swift reached 47 million views on X (formerly Twitter) before the platform finally suspended the user who had shared them.

It is not hard to imagine the damage that such content can do to an individual’s mental health. But if applied on an even broader scale, such as in the context of an election, it could threaten entire populations. The AI Act offers a straightforward response to this problem. AI-generated content will have to be labeled as such, so that everyone knows immediately that it is not real. That means providers will have to design systems in a way that synthetic audio, video, text, and images are marked in a machine-readable format, and detectable as artificially generated or manipulated.

Companies will be given a chance to bring their systems into compliance with the regulation. If they fail to comply, they will be fined. Fines would range from €35 million ($58 million) or 7% of global annual turnover (whichever is higher) for violations of banned AI applications; €15 million or 3% for violations of other obligations; and €7.5 million or 1.5% for supplying incorrect information. But fines are not all. Noncompliant AI systems will also be prohibited from being placed on the EU market.

Europe is the first mover on AI regulation, but our efforts are already helping to mobilize responses elsewhere. As many other countries start to embrace similar frameworks—including the United States, which is collaborating with Europe on ‘a risk-based approach to AI to advance trustworthy and responsible AI technologies’—we feel confident that our overall approach is the right one. Just a few months ago, it inspired G7 leaders to agree on a first-of-its-kind Code of Conduct on Artificial Intelligence. These kinds of international guardrails will help keep users safe until legal obligations start kicking in.

AI is neither good nor bad, but it will usher in a global era of complexity and ambiguity. In Europe, we have designed a regulation that reflects this. Probably more than any other piece of EU legislation, this one required a careful balancing act—between power and responsibility, between innovation and trust, and between freedom and safety.

In Poznan, 325 kilometers east of Warsaw, a team of tech researchers, engineers, and child caregivers are working on a small revolution. Their joint project, ‘Insension’, uses facial recognition powered by artificial intelligence to help children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities interact with others and with their surroundings, becoming more connected with the world. It is a testament to the power of this quickly advancing technology.

Thousands of kilometers away, in the streets of Beijing, AI-powered facial recognition is used by government officials to track citizens’ daily movements and keep the entire population under close surveillance. It is the same technology, but the result is fundamentally different. These two examples encapsulate the broader AI challenge: the underlying technology is neither good nor bad in itself; everything depends on how it is used.

AI’s essentially dual nature informed how we chose to design the European Artificial Intelligence Act, a regulation focused on the uses of AI, rather than on the technology itself. Our approach boils down to a simple principle: the riskier the AI, the stronger the obligations for those who develop it.

AI already enables numerous harmless functions that we perform every day—from unlocking our phones to recommending songs based on our preferences. We simply do not need to regulate all these uses. But AI also increasingly plays a role at decisive moments in one’s life. When a bank screens someone to determine if she qualifies for a mortgage, it isn’t just about a loan; it is about putting a roof over her head and allowing her to build wealth and pursue financial security. The same is true when employers use emotion-recognition software as an add-on to their recruitment process, or when AI is used to detect illnesses in brain images. The latter is not just a routine medical check; it is literally a matter of life or death.

In these kinds of cases, the new regulation imposes significant obligations on AI developers. They must comply with a range of requirements—from running risk assessments to ensuring technical robustness, human oversight, and cybersecurity—before releasing their systems on the market. Moreover, the AI Act bans all uses that clearly go against our most fundamental values. For example, AI may not be used for social scoring or subliminal techniques to manipulate vulnerable populations, such as children.

Though some will argue that this high-level control deters innovation, in Europe we see it differently. For starters, time-blind rules provide the certainty and confidence that tech innovators need to develop new products. But more to the point, AI will not reach its immense positive potential unless end-users trust it. Here, even more than in many other fields, trust serves as an engine of innovation. As regulators, we can create the conditions for the technology to flourish by upholding our duty to ensure safety and public trust.

Far from challenging Europe’s risk-based approach, the recent boom of general-purpose AI (GPAI) models like ChatGPT has made it only more relevant. While these tools help scammers around the world produce alarmingly credible phishing emails, the same models also could be used to detect AI-generated content. In the space of just a few months, GPAI models have taken the technology to a new level in terms of the opportunities it offers, and the risks it has introduced.

Of course, one of the most daunting risks is that we may not always be able to distinguish what is fake from what is real. GPAI-generated deepfakes are already causing scandals and hitting the headlines. In late January, fake pornographic images of the global pop icon Taylor Swift reached 47 million views on X (formerly Twitter) before the platform finally suspended the user who had shared them.

It is not hard to imagine the damage that such content can do to an individual’s mental health. But if applied on an even broader scale, such as in the context of an election, it could threaten entire populations. The AI Act offers a straightforward response to this problem. AI-generated content will have to be labeled as such, so that everyone knows immediately that it is not real. That means providers will have to design systems in a way that synthetic audio, video, text, and images are marked in a machine-readable format, and detectable as artificially generated or manipulated.

Companies will be given a chance to bring their systems into compliance with the regulation. If they fail to comply, they will be fined. Fines would range from €35 million ($58 million) or 7% of global annual turnover (whichever is higher) for violations of banned AI applications; €15 million or 3% for violations of other obligations; and €7.5 million or 1.5% for supplying incorrect information. But fines are not all. Noncompliant AI systems will also be prohibited from being placed on the EU market.

Europe is the first mover on AI regulation, but our efforts are already helping to mobilize responses elsewhere. As many other countries start to embrace similar frameworks—including the United States, which is collaborating with Europe on ‘a risk-based approach to AI to advance trustworthy and responsible AI technologies’—we feel confident that our overall approach is the right one. Just a few months ago, it inspired G7 leaders to agree on a first-of-its-kind Code of Conduct on Artificial Intelligence. These kinds of international guardrails will help keep users safe until legal obligations start kicking in.

AI is neither good nor bad, but it will usher in a global era of complexity and ambiguity. In Europe, we have designed a regulation that reflects this. Probably more than any other piece of EU legislation, this one required a careful balancing act—between power and responsibility, between innovation and trust, and between freedom and safety.

Artificial Intelligences are not people. They don’t think in the way that people do and it is misguided, or even possibly dangerous, to anthropomorphise them. But it can be helpful to consider the similarities between humans and AIs from one perspective—their roles in society.

Regardless of the differences between AI models and human brains, AIs are increasingly interacting with and impacting people in the real world, including taking on roles traditionally performed by humans. Unlike previous technologies that have influenced and reshaped society, AIs are able to reason, make decisions and act autonomously, which feels distinctly human. The more we adopt and come to depend on them in everyday life, particularly those with pretty and intuitive interfaces, the easier it is to expect them to operate like people do. Yet at their core, they don’t.

AIs have a place in human society, but they aren’t of it, and they won’t understand our rules unless explicitly told. Likewise, we need to figure out how to live with them. We need to define some AI equivalents to the rules, values, processes and standards that have always applied to people. These structures have built up and evolved over the long history of humanity, and society is complex, containing many unwritten rules, such as ‘common sense’, that we still struggle to explain today. So, we will need to do some clever thinking about this.

Addressing these challenges should start with getting the right people thinking about it. We usually consult technologists and the technology sector for AI-related topics, but they cannot—and should not—be responsible for solving all of the challenges of AI. Last year, international thought leaders in AI called for a pause on technical AI research and development, which might be justified to give our governments and wider society time to adapt. However, unless we get much broader participation in AI by those same communities, any pause simply delays the inevitable and can give adversaries a lead in shaping the emerging technology landscape away from our interests.

So, let’s think more holistically about how to grow AIs into productive contributors to society. One way to do this is to consider some illustrative similarities with raising children.

When parents first decide to have children, a significant amount of time, effort and money can go into making a baby, with each child taking a fixed time (around nine months) to physically create. But the far greater investment comes after the birth as the family raises the child into an adult over the next 20 or more years.

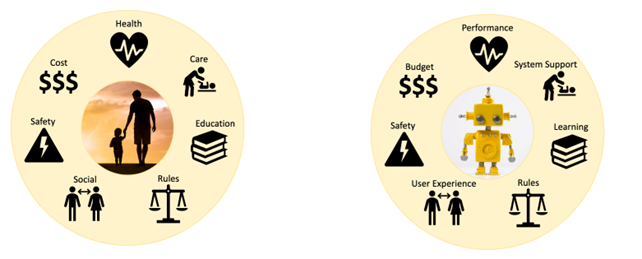

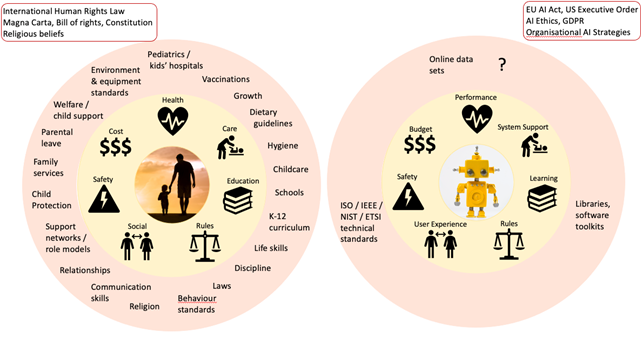

Figure 1: Some considerations for raising a human vs raising an AI.

Raising kids is not easy—parents have an enormous range of decisions to make about a child’s health, education, social skills, safety, and the appropriate rules and boundaries at each stage as it develops into a well-adjusted and productive member of society. Over time, society has created institutions, laws, frameworks and guidance to support parents and help them make the best decisions they can for their families.

These include institutions such as paediatric hospitals, schools, and childcare facilities. We have child welfare and protection laws. Schools use learning curricula from K-12 and books that are ‘age appropriate’. We have expected standards for behavioural, social and physical development as children grow. Parents are provided diet recommendations (the ‘food pyramid’) and vaccination schedules for their child’s health and wellbeing. Entire industries make toys, play equipment and daily objects that are safe for children to use and interact with.

Yet in the case of AI, we are collectively preoccupied with being pregnant.

Most of the discussions are about making the technology. How do we create it? Is the tech fancy enough? Is the algorithm used to create the model the right choice? Certainly, a large effort is needed to create the first version of a new model. But once that initial work is done, software can be cloned and deployed extremely quickly unlike with a child. This means the creation is an important, but relatively small, part of an average AI’s lifespan, while the rearing phase is long and influential, and gets comparatively overlooked in planning.

A good way to start thinking about ‘raising’ AIs is by recognising that the institutions, frameworks and services that society has for young, growing humans will have equivalents for young, growing AIs, only with different names.

So, instead of talking about the health of an AI, we’re really talking about whether its performance is fit for its purpose. This can include whether we have the right infrastructure or clean data for the problem. Is the data current and appropriate? Do we have enough computing power, responsiveness and resilience built into the system for it to make decisions in the timeframes needed—for example, milliseconds in the case of real-time operations for drone piloting as opposed to hours, days or weeks for research results? Are we updating the model regularly enough or have we let the model drift over time? We can also inoculate AI systems against some kinds of damage or manipulation, in a similar way to vaccinating for diseases, by using small amounts of carefully crafted ‘bad’ data called adversarial examples to build resistance into machine learning models.

Rather than care and feeding in the case of humans, we talk about system support and maintenance over the AI’s lifetime. This includes how we check in to make sure it’s still doing well and make adjustments for different stages of its development. We need to ensure it has enough power and cooling for the computations we want it to make, that it has sufficient memory and processing, and that we are managing and securing the data appropriately. We need to know what the software patching lifecycle will look like, and for how long we expect the system to live, noting the rapid pace of technology. This is closely related to budget, because upfront build costs can be eclipsed by the costs of supporting a system over the long term. Keeping runtime costs affordable and reducing the environmental impact might mean we need to limit the scope of some AIs, to ensure they deliver value for the users.

In place of education, we consider machine learning and the need to make sure that what an AI is learning is accurate, ‘age appropriate’ (depending on whether we are giving it simple or complex tasks), and is using expert sources of information rather than, for example, random Internet blogs as references. Much like a young child, early AIs such as the first version of ChatGPT (based on GPT-3) were notorious for making things up or ‘hallucinating’ based on what it thought the user wanted to hear. Systems, like people, need to learn from their experiences and mistakes to grow to have more nuanced, informed views.

Rules in AIs are the boundaries we set for what we want them to do and how we want them to work—when we allow autonomy, when we won’t, how we want them to be accountable—much like for people. Many rules around AI talk about explainability and transparency, worthy goals to understand how a system works but not always as helpful as they sound. Often, they refer to being able to, for instance, recreate and observe the state of a model at a specific point in time, comparable to mapping how a thought occurs in the brain by tracing the electrical pathways. But neither of these is great at explaining the reason for, or the fairness of, that decision. More helpfully, a machine learning model can be run thousands of times over and assessed by its results in a range of scenarios to determine if it is ‘explainably fair’, and then tweaked so that we’re happier with the answers. This form of correction or rehabilitation is ultimately more useful for serving the real-world needs of people than the description of a snapshot of memory.

User experience (UX) and user interface design are similar to growing children’s social skills, enabling them to communicate and explain information and assessments they’ve made in a way that others can understand. Humans, at the best of times, aren’t particularly comfortable with statistics and the language of mathematics, so its critically important to design intuitive ways for people to interpret an AI’s output, in particular taking into account what the AI is, and isn’t, capable of. It’s easier with young humans because we each have an innate understanding of children, given we were once children ourselves. When we interact with them, we know what to expect. This is less true of Ais—we don’t trust a machine in the way we trust humans because we may not understand its reasoning, biases or exactly what it is attempting to say. We also don’t necessarily communicate in a way that the AI needs either. Engaging with ChatGPT has taught us to change how we ask questions and be very specific in defining the problem and its boundaries. This is a challenge for developers and society where both sides need to learn and improve.

Safety can be thought of in several ways in the context of AI. It can mean the safety of the users—whether that’s their physical or financial safety from bad decisions by the AI, or their susceptibility to being negatively influenced by it. But it also means the protection of the AI itself against damage or adverse effects. The concept of digital safety in an online world is understood (if not practised) by the public, and much discussion about AI safety in the media is dedicated to the risk that an AI ‘goes rogue’. Care must be taken to mitigate against unintended consequences when we rely on AIs, particularly for things they’re not well designed for. But far too little time is dedicated to AI security, and considering whether an AI can be actively manipulated or disrupted. Active exploitation of an AI by a malicious adversary seeking to undermine social structures, values and safeguards could have an enormous impact, particularly when we consider the potential reach of large-scale AIs or AIs embedded into critical systems. We will need to use adversarial machine learning, penetration testing, red-teaming and holistic security assessments (including physical, personnel, data and cyber security) to identify vulnerabilities, monitor for bad actors and make our AIs as difficult as possible to exploit. AI security will be a critical growth area in years to come and a focus for defence and national security communities around the world.

Figure 2: Laws, frameworks and guidelines for raising a human vs raising an AI.

Much of the time when we discuss AI, we either talk about ethics and safety at a high level—such as through transparency, accountability and fairness—or we talk about algorithms, deep in the weeds of the technology. All these aspects are important to understand. But what’s largely missing in the AI discussion is the space in between, where we need to have guidance and frameworks for AI developers and customers.

In the same way we would not expect (nor want) technologists to make decisions about child welfare laws, we should not leave far-reaching decisions about the use of AI to today’s ‘AI community’, which is almost exclusively scientists and engineers. We need teachers, lawyers, philosophers, ethicists, sociologists and psychologists to help set bounds and standards that shape what we want AI to do, what we keep in human hands and what we want a future AI-enabled society to look like.

We need entrepreneurs and experts in the problem domains, project managers, finance and security experts who know how to deliver what is needed, at a price and risk threshold that we can accept. And we need designers, user experience (UX) specialists, and communicators to shape how an AI reports its results, how those results are interpreted by a user and how we can do this better so that we head off misunderstandings and misinformation.

There are many lessons for technology from the humanities. Bringing people together from across all these disciplines, not just the technical ones, must form a part of any strategy for AI. And this must come with commensurate investment. Scholarships and incentives in academia for AI research should be extended well beyond the STEM disciplines. They should help develop and support new multidisciplinary collaborative groups to look at AI challenges, such as the Australian Society for Computers & Law.

Just as it takes a village to raise a child, the governing of AI needs to be a multidisciplinary village so that we can raise AIs that are productive, valued contributors to society.

Following the recent AI Safety Summit hosted by British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, ASPI’s Bart Hogeveen speaks with the European Union’s Senior Envoy for Digital to the United States Gerard de Graaf. They discuss the EU’s approach to AI regulation and how it differs from what the US and other governments are doing. They also discuss which uses of AI the EU thinks should be limited or prohibited and why, and provide suggestions for Australia’s efforts to regulate AI.

Next, ASPI’s Alex Caples, speaks to Australian Federal Police Commander Helen Schneider. They discuss the AFP and Monash University initiative ‘My Pictures Matter’, which uses AI to help combat child exploitation. They also explore the importance of using an ethically sourced database to train the AI tool that is used in the project, and outline how people can get involved in the campaign and help end child exploitation in Australia and overseas.

The Beijing Internet Court’s ruling that content generated by artificial intelligence can be covered by copyright has caused a stir in the AI community, not least because it clashes with the stances adopted in other major jurisdictions, including the United States. In fact, that is partly the point: the ruling advances a wider effort in China to surpass the US to become a global leader in AI.

Not everyone views the ruling as all that consequential. Some commentators point out that the Beijing Internet Court is a relatively low-level institution, operating within a legal system where courts are not obligated to follow precedents. But, while technically true, that interpretation misses the point, because it focuses narrowly on Chinese law, as written. In the Chinese legal context, decisions like this one both reflect and shape policy.

In 2017, China’s leaders set the ambitious goal of achieving global AI supremacy by 2030. But the barriers to success have proved substantial—and they continue to multiply. Over the past year or so, the US has made it increasingly difficult for China to acquire the chips it needs to develop advanced AI technologies, such as large language models, that can compete with those coming out of the US. President Joe Biden’s administration further tightened those regulations in October.

In response to this campaign, China’s government has mobilised a whole-of-society effort to accelerate AI development, channelling vast investment toward the sector and limiting regulatory hurdles. In its interim measures for generative AI services—which entered into effect in August—the government urged administrative authorities and courts at all levels to adopt a cautious and tolerant regulatory stance toward AI.

If the Beijing Internet Court’s recent ruling is any indication, the judiciary has taken that guidance to heart. After all, making it possible to copyright some AI-generated content not only directly strengthens the incentive to use AI, but also boosts the commercial value of AI products and services.

Conversely, denying copyrights to AI-generated content could inadvertently encourage deceptive practices, with digital artists being tempted to misrepresent the origins of their creations. By blurring the lines between AI-generated and human-crafted works, this would pose a threat to the future development of AI foundational models, which rely heavily on training with high-quality data sourced from human-generated content.

For the US, the benefits of prohibiting copyright protection for AI-generated content seem to outweigh the risks. The US Copyright Office has refused to recognise such copyrights in three cases, even if the content reflects a substantial human creative or intellectual contribution. In one case, an artist tried more than 600 prompts—a considerable investment of effort and creativity—to create an AI-generated image that eventually won an award in an art competition, only to be told that the copyright would not be recognised.

This reluctance is hardly unfounded. While the Beijing Internet Court ruling might align with China’s AI ambitions today, it also opens a Pandora’s box of legal and ethical challenges. For instance, as creators of similar AI artworks dispute copyright infringement, Chinese courts could be burdened by a surge of litigation at a time when they must face the contentious issue of whether copyright holders can obtain compensation for the use of their AI-generated works in AI training. This makes a revision of existing copyright laws and doctrines by Chinese courts and the legislature all but inevitable.

Questions about copyrights and AI training are already fuelling heated debates in a number of jurisdictions. In the US, artists, writers and others have launched a raft of lawsuits accusing major AI firms like OpenAI, Meta and Stability AI of using their copyrighted work to train AI systems without permission. In Europe, the proposed AI act requires that companies disclose any copyrighted materials they use for training generative AI systems—a rule that would make AI firms vulnerable to copyright-infringement suits, while increasing the leverage of copyright holders in compensation negotiations.

For China, addressing such questions might prove to be particularly complicated. Chinese law permits the free use of copyrighted materials only in very limited circumstances. But with Chinese courts increasingly aligning their rulings with directives from Beijing, it seems likely that, to facilitate the use of copyrighted materials by AI firms, they will soon start taking a laxer approach and approve a growing number of exceptions.

The price, however, could be steep. The adoption of a more lenient approach to the use of copyrighted materials for AI training—as well as the likely flood of AI-generated content on the Chinese market—may end up discouraging human creativity in the long term.

From the government to the courts, Chinese authorities seem fixated on ensuring that the country can lead on AI. But the consequences of their approach could be profound and far-reaching. It is not inconceivable that this legal trend could lead to social crises such as massive job losses in creative industries and widespread public discontent. For now, however, China can be expected to continue nurturing its AI industry—at all costs.

In the grand tapestry of technological evolution, generative artificial intelligence has emerged as a vibrant and transformative thread. Its extraordinary benefits are undeniable; already it is revolutionising industries and reshaping the way we live, work and interact.

Yet as we stand on the cusp of this new era—one that will reshape the human experience—we must also confront the very real possibility that it could all unravel.

The duality of generative AI demands that we navigate its complexities with care, understanding and foresight. It is a world where machines—equipped with the power to understand and create—generate content, art and ideas with astonishing proficiency. And realism.

The story of generative AI thus far is one of mesmerising achievements and chilling consequences. Of innovation and new responsibilities. Of progress and potential peril.

From Web 1.0 to generative AI: the evolution of the internet and its impact on human rights

We’ve come a long way since Web 1.0, where users could only read and publish information; a black-and-white world where freedom of expression, simply understood, quickly became a primary concern.

Web 2.0 brought new interactive and social possibilities. We began to use the internet to work, socialise, shop, create and play—even find partners. Our experience became more personal as our digital footprint became ever larger, underscoring the need for users’ privacy and security to be baked in to the development of digital systems.

The wave of technological change we’re witnessing today promises to be even more transformative. Web 3.0 describes a nascent stage of the internet that is decentralised and allows users to exchange directly content they own or have created. The trend towards decentralisation and the development of technologies such as virtual reality, augmented reality and generative AI are bringing us to an entirely new frontier.

All of this is driving a deeper awareness of technology’s impact on human rights.

Rights to freedom of expression and privacy are still major concerns, but so are the principles of dignity, equality and mutual respect, the right to non-discrimination, and rights to protection from exploitation, violence and abuse.

For me, as Australia’s eSafety Commissioner, one vital consideration stands out: the right we all have to be safe.

Concerns we can’t ignore

We have seen extraordinary developments in generative AI over the past 12 months that underline the challenges we face in protecting these rights and principles.

Deepfake videos and audio recordings, for example, depict people in situations they never engaged in or experienced. Such technical manipulation may go viral before the authenticity—or falsehood—can be proven. This can have serious repercussions for not only an individual’s reputation or public standing, but also their fundamental wellbeing and identity.

Experts have long been concerned about the role of generative AI in amplifying and entrenching biases in training data. These models may then perpetuate stereotypes and discrimination, fuelling an untrammelled cycle of inequality at an unprecedented pace and scale.

And generative AI poses significant risks in creating synthetic child sexual abuse material. This harm is undeniable; all content that normalises child sexualisation and AI-generated versions of it hamper law enforcement.

eSafety’s hotline and law-enforcement queues are starting to fill with synthetic child sexual abuse material, presenting massive new resourcing and triaging challenges.

We are also very concerned about the potential of manipulative chatbots to further weaponise the grooming and exploitation of vulnerable young Australians.

These are not abstract concerns; incidents of abuse are already being reported to us.

The why: stating the case for safety by design in generative AI

AI and virtual reality are creating new actual realities that we must confront as we navigate the complexities of generative AI.

Doing so effectively requires a multi-faceted approach that involves technology, policy and education.

By making safety a fundamental element in the design of generative AI systems, we put individuals’ wellbeing first and reduce both users’ and developers’ exposure to risk.

As has been articulated often over the past several months and seems to be well understood, safety needs to be a pre-eminent concern, not retrofitted as an afterthought, or after systems have been ‘extricated out into the wild’.

Trust in the age of AI is a paramount consideration given the scale of potential harm to individuals and society, even to democracy and humanity itself.

The how: heeding the lessons of history by adopting safety by design for generative AI

How can we establish this trust?

Just as the medical profession has the Hippocratic Oath, we need to see a well-integrated credo in model and systems design that is in direct alignment with the imperative, ‘first, do no harm’.

To achieve this, identifying potential harms and misuse scenarios is crucial. We need to consider the far-reaching effects of AI-generated content—not just for today but for tomorrow.

Some of the efforts around content authenticity and provenance standards through watermarking and more rapid deepfake-detection tools should be an immediate goal.

As first steps, users also need to know when they are interacting with AI-generated content, and the decision-making processes behind AI systems must be more transparent.

User education on recognising and reporting harmful content must be another cornerstone of our approach. Users need to have control over AI-generated content that impacts them. This includes options to filter or block such content and personalise AI interactions.

Mindful development of content moderation, reporting mechanisms and safety controls can ensure harmful synthetic content and mistruths don’t go viral at the speed of sound without meaningful recourse.

But safety commitments must extend beyond design, development and deployment. We need continuous vigilance and auditing of AI systems in real-world applications for swift detection and resolution of issues.

Human oversight by reviewers adds an extra layer of protection. And empowering developers responsible for AI with usage training and through company and industry performance metrics is also vital.

The commitment to safety must start with company leadership and be inculcated into every layer of the tech organisation, including incentives for engineers and product designers for successful safety interventions.

The whole premise of Silicon Valley legend John Doerr’s 2018 book, Measure what matters, provided tech organisations with a blueprint for developing objectives and key results instead of the traditional key performance indicators.

What matters now with the tsunami of generative AI is that industry not only gets onto the business of measuring its safety success at the company, product and service level, but also sets tangible safety outcomes and measurements for the broader AI industry.

Indeed, the tech industry needs to measure what matters in the context of AI safety.

Regulators should be resourced to stress-test AI systems to uncover flaws, weaknesses, gaps and edge cases. We are keen to build regulatory sandboxes.

We need rigorous assessments before and after deployment to evaluate the societal, ethical and safety implications of AI systems.

Clear crisis-response plans are also necessary to address AI-related incidents promptly and effectively.

The role of global regulators in an online world of constant change

How can we make sure the tech industry plays along?

Recent pronouncements, principles and policies from industry are welcome. They can help lay the groundwork for safer AI development.

For example, TikTok, Snapchat and Stability AI, along with 24 other organisations—including the US, German and Australian governments—have pledged to combat child sexual abuse images generated by AI. This commitment was announced by Britain ahead of a global AI safety summit later this week. The pledge focuses on responsible AI use and collaborative efforts to prevent AI-related risks in addressing child sexual abuse.

Such commitments won’t amount to much without measurement and external validation, which is partly why we’re seeing a race by governments globally to implement the first AI regulatory scheme.

US President Joe Biden’s new executive order on AI safety and security, for example, mandates AI model developers to share safety test results. This order addresses national security, data privacy and public safety concerns related to AI technology. The White House views it as a significant step in AI safety.

With other governments pursing their own reforms, there’s a danger of plunging headlong into a fragmented splinternet of rules.

What’s needed instead is a harmonised legislative approach which recognises sovereign nations and regional blocs will take slightly different paths. A singular global agency to oversee AI would likely be too cumbersome and slow to deal with the issues we need to rectify now.

Global regulators—whether focused on safety, privacy, competition or consumer rights—can work towards best-practice AI regulation in their domains, building from current frameworks. And we can work across borders and boundaries to achieve important gains.

Last November, eSafety launched the Global Online Safety Regulators Network with the UK, Ireland and Fiji. We’ve since increased our membership to include South Korea and South Africa, and have a broader group of observers to the network.

As online safety regulation pioneers, we strive to promote a unified global approach to online safety regulation, building on shared insights, experiences and best practices.

In September 2023, the network had its inaugural in-person meeting in London, and issued its first position statement on the important intersection of human rights in online safety regulation.

Our guiding principles are rooted in the broad sweep of human rights, including protecting children’s interests, upholding dignity and equality, supporting freedom of expression, ensuring privacy and preventing discrimination.

It is crucial that safeguards coexist with freedoms, and we strongly believe that alleviating online harms can further bolster human rights online.

In the intricate relationship between human rights and online safety, no single right transcends another. The future lies in a proportionate approach to regulation that respects all human rights.

This involves governments, regulators, businesses and service providers cooperating to prevent online harm and enhance user safety and autonomy, while allowing freedom of expression to thrive.

To make cyberspace more defensible—a goal championed by Columbia University and called for in the 2023 US National Cybersecurity Strategy—innovations must not just strengthen defences, but give a sustained advantage to defenders relative to attackers.

Artificial intelligence has the potential to be a game-changer for defenders. As a recent Deloitte report put it, ‘AI can be a force multiplier, enabling security teams not only to respond faster than cyberattackers can move but also to anticipate these moves and act in advance’.

Yet this is no less true if we switch it around: AI can enable cyberattackers to move faster than defenders can respond.

Even the best defensive advances have been quickly overtaken by greater leaps made by attackers, who have long had the systemic advantage in cyberspace. As security expert Dan Geer said in 2014, ‘Whether in detection, control or prevention, we are notching personal bests, but all the while the opposition is setting world records’. Most dishearteningly, many promising defences—such as ‘offensive security’ to crack passwords or scan networks for vulnerabilities—have ended up boosting attackers more than defenders.

For AI to avoid this fate, defenders, and those that fund new research and innovation, must remember that AI is not a magic wand that grants lasting invulnerability. For defenders to win the cybersecurity arms race in AI, investments must be constantly refreshed and well targeted to stay ahead of threat actors’ own innovative use of AI.

It’s hard to assess which side AI will assist more, the offense or the defence, since each is unique. But such apples-to-oranges comparisons can be clarified using two widely used frameworks.

The US National Institute of Standards and Technology’s Cybersecurity Framework can be used to highlight the many ways AI can help defence, while the Cyber Kill Chain framework, developed by Lockheed Martin, can do the same for AI’s uses by attackers.

This more structured approach can help technologists and policymakers target their investments and ensure that AI doesn’t follow the path of so many other technologies, nudging along defenders but turbocharging the offence.

Gains from AI for the defence

The NIST framework is an ideal architecture to cover all the ways AI might aid defenders. Table 1, while not meant to be a complete list, serves as an introduction.

Table 1: Using the NIST framework to categorise AI advantages for defenders

| NIST framework function | Ways AI might radically improve defence |

| Identify | – Rapid automated discovery of an organisation’s devices and software |

| – Easier mapping of an organisation’s supply chain and its possible vulnerabilities and points of failure | |

| – Identification of software vulnerabilities at speed and scale | |

| Protect | – Reduce demand for trained cyber defenders |

| – Reduce skill levels necessary for cyber defenders | |

| – Automatically patch software and associated dependencies | |

| Detect | – Rapidly spot attempted intrusions by examining data at scale and speed, with few false-positive alerts |

| Respond | – Vastly improved tracking of adversary activity by rapidly scanning logs and other behaviour |

| – Automatic ejection of attackers, wherever found, at speed | |

| – Faster reverse-engineering and de-obfuscation, to understand how malware works to more quickly defeat and attribute it | |

| – Substantial reduction in false-positive alerts for human follow-up | |

| Recover | – Automatically rebuild compromised infrastructure and restore lost data with minimum downtime |

Even though this is just a subset, there are still substantial gains, especially if AI can drastically reduce the number of highly skilled defenders. Unfortunately, most of the other gains are directly matched by corresponding gains to attackers.

Gains from AI for the offence

While the NIST framework is the right tool for the defence, Lockheed Martin’s Cyber Kill Chain is a better framework for assessing how AI might boost the attacker side of the arms race, an idea earlier proposed by American computer scientist Kathleen Fisher. (MITRE ATT&CK, another offence-themed framework, may be even better but is substantially more complex than can be easily examined in a short article.)

Table 2: Using the Cyber Kill Chain framework to categorise AI advantages for attackers

| Phase of Cyber Kill Chain framework | Ways AI might radically improve offence |

| Reconnaissance | – Automatically find, purchase and use leaked and stolen credentials |

| – Automatically sort to find all targets with a specific vulnerability (broad) or information on a precise target (deep; for example, an obscure posting that details a hard-coded password) | |

| – Automatically identify supply-chain or other third-party relationships that might be affected to impact the primary target | |

| – Accelerate the scale and speed at which access brokers can identify and aggregate stolen credentials | |

| Weaponisation | – Automatically discover software vulnerabilities and write proof-of-concept exploits, at speed and scale |

| – Substantially improve obfuscation, hindering reverse-engineering and attribution | |

| – Automatically write superior phishing emails, such as by reading extensive correspondence of an executive and mimicking their style | |

| – Create deepfake audio and video to impersonate senior executives in order to trick employees | |

| Delivery, exploitation and installation | – Realistically interact in parallel with defenders at many organisations to convince them to install malware or do the attacker’s bidding |

| – Generating false attack traffic to distract defenders | |

| Command and control | – Faster breakout: automated privilege escalation and lateral movement |

| – Automatic orchestration of vast numbers of compromised machines | |

| – Ability for implanted malware to act independently without having to communicate back to human handlers for instructions | |

| Actions on objectives | – Automated covert exfiltration of data with a less detectable pattern |

| – Automated processing to identify, translate and summarise data that meets specified collection requirements |

Again, even though this is just a likely subset of the many ways AI will aid the offence, it demonstrates the advantage that it can bring, especially when the categories are combined.

Analysis and next steps

Unfortunately, general-purpose technologies have historically advantaged the offence, since defenders are spread out within and across organisations, while attackers are concentrated. To deliver their full benefit, defensive innovations usually need to be implemented in thousands of organisations (and sometimes by billions of people), whereas focused groups of attackers can incorporate offensive innovations with greater agility.

This is one reason why AI’s greatest help to the defence may be in reducing the number of cyber defenders required and the level of skills they need.

The US alone needs hundreds of thousands of additional cybersecurity workers—positions that are unlikely ever to be filled. Those who are hired will take years to build the necessary skills to take on advanced attackers. Humans, moreover, struggle with complex and diffuse tasks like defence at scale.

As more organisations move their computing and network tasks to the cloud, the major service providers will be well placed to concentrate AI-driven defences. The scale of AI might completely revolutionise defence, not just for the few that can afford advanced tools but for everyone on the internet.

The future is not written in stone but in code. Smart policies and investments now can make a major difference to tip the balance to the defence in the AI arms race. For instance, the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency—responsible for the development of technologies for use by the military—is making transformative investments, apparently having learned from experience.

In 2016, DARPA hosted the final round of its Cyber Grand Challenge to create ‘some of the most sophisticated automated bug-hunting systems ever developed’. But these computers were playing offence as well as defence. To win, they ‘needed to exploit vulnerabilities in their adversaries’ software’ and hack them. Autonomous offensive systems may be a natural investment for the military, but unfortunately would boost the offence’s advantages.

DARPA’s new experiment, the AI Cyber Challenge, is purely defensive—with no offensive capture-the-flag component—‘to leverage advances in AI to develop systems that can automatically secure the critical code that underpins daily life’. With nearly US$20 million of prize money, and backed by leading companies in AI (Anthropic, Google, Microsoft and OpenAI), this DARPA challenge could revolutionise software security.

These two challenges encapsulate the dynamics perfectly: technologists and policymakers need to invest so that defensive AIs are faster at finding vulnerabilities and patching them and their associated dependencies within an enterprise than offensive AIs are at discovering, weaponising and exploiting those vulnerabilities.

With global spending on AI for cybersecurity forecast to increase by US$19 billion between 2021 and 2025, the opportunity to finally give the defence an advantage over the offence has rarely looked brighter.

Thinking and learning about artificial intelligence are the mental equivalent of a fission chain reaction. The questions get really big, really quickly.

The most familiar concerns revolve around short-term impacts: the opportunities for economic productivity, health care, manufacturing, education, solving global challenges such as climate change and, on the flip side, the risks of mass unemployment, disinformation, killer robots, and concentrations of economic and strategic power.

Each of these is critical, but they’re only the most immediate considerations. The deeper issue is our capacity to live meaningful, fulfilling lives in a world in which we no longer have intelligence supremacy.

As long as humanity has existed, we’ve had an effective monopoly on intelligence. We have been, as far as we know, the smartest entities in the universe.

At its most noble, this extraordinary gift of our evolution drives us to explore, discover and expand. Over the past roughly 50,000 years—accelerating 10,000 years ago and then even more steeply from around 300 years ago—we’ve built a vast intellectual empire made up of science, philosophy, theology, engineering, storytelling, art, technology and culture.

If our civilisations—and in varying ways our individual lives—have meaning, it is found in this constant exploration, discovery and intellectual expansion.

Intelligence is the raw material for it all. But what happens when we’re no longer the smartest beings in the universe? We haven’t yet achieved artificial general intelligence (AGI)—the term for an AI that could do anything we can do. But there’s no barrier in principle to doing so, and no reason it wouldn’t quickly outstrip us by orders of magnitude.

Even if we solve the economic equality questions through something like a universal basic income and replace notions of ‘paid work’ with ‘meaningful activity’, how are we going to spend our lives in ways that we find meaningful, given that we’ve evolved to strive and thrive and compete?

Picture the conflict that arises for human nature if an AGI or ASI (artificial superintelligence) could answer all of our most profound questions and solve all of our problems. How much satisfaction do we get from having the solutions handed to us? Worse still, imagine the wistful sense of consolation at being shown an answer and finding we’re too stupid to understand it.

Eventually, we’re going to face the prospect that we’re no longer in charge of our civilisation’s intelligence output. If that seems speculative, we’re actually already creeping in that direction with large language models. Ask ChatGPT to write an 800-word opinion article on, say, whether the Reserve Bank of Australia should raise interest rates further. It does a decent job—not a brilliant one, but a gullible editor would probably publish it and it certainly could be used as the basis for a sensible dinner party conversation. You might edit it, cherrypick the bits you agree with and thereby tell yourself these are your views on the issue. But they’re not; they’re ChatGPT’s views and you’re going along with them.

Generative AI is an amazing achievement and a valuable resource, but we have to be clear-eyed about where these tools might take us.

This is not about AI going wrong. To be sure, there’s a pressing urgency for more work on AI alignment so that we don’t give powerful AIs instructions that sound sensible but go horribly wrong because we can never describe exactly what we want. AI pioneer Stuart Russell has compared this to the King Midas story. Turning everything into gold by touching it sounds fantastic until you try to eat an apple or hug your kids.

But beyond alignment lies the question of where we’re left, even if we get it all right. What do we do with ourselves?

Optimistic commentators argue that human opportunities will only expand. After all, there have been great breakthroughs in the past that enhanced us rather than made us redundant. But AGI is categorically different.

Horses and machines replaced our muscles. Factories replaced our organised physical labour. Instruments such as calculators and computers have replaced specific mental tasks, while communications technology improves our cooperation and hence our collective intelligence. Narrow AI can enhance us by freeing us from routine tasks, enabling us to concentrate on higher level strategic goals and improving our productivity. But with AGI, we’re talking about something that could supersede all applications of human intelligence. A model that can plan, strategise, organise, pursue very high-level directions and even form its own goals would leave an ever-diminishing set of tasks for us to do ourselves.

The physicist Max Tegmark, co-founder of the Future of Life Institute, has compared AGI to a rising ocean, with human intellectual tasks occupying shrinking land masses that eventually become small islands left for our intelligence to perch on.

One thing we will keep is our humanness. Freedom to spend more time doing what we want should be a gift. We can spend more time being parents, spouses, family members, friends, social participants—things that by definition only humans can fully give to other humans. The slog of paid work need not be the only thing that gives us meaning—indeed it would be sad if we fell apart without it.

Equally, we have always earned our living since we hunted and gathered, so a transition to a post-scarcity, post-work world will be a social experiment like no other. Exercising our humanness towards one another might continue to be enough, but we will need to radically reorientate our customs and beliefs about what it means to be a valued member of the human race. (Even our humanness might be an eroding land mass; generative AI’s creative powers and ability to simulate empathy have already reached levels we didn’t anticipate just a couple of years ago.)

A real possibility is that we integrate our brains with AI to avoid being left behind by it. Elon Musk’s Neuralink is the best-known enterprise in this field, but there’s plenty of other work going on. Maybe humans will keep up with AI by merging with it, but then that raises the question of at what point we diverge from being human.

Maybe you’re a transhumanist or a technology futurist and you just don’t care whether the intelligence that inherits the world is recognisably human or even biological. What does it matter? Maybe we should bequeath this great endowment to silicon and accept that we were only ever meant to be a spark that ignited the true god-like power of intelligence on other substrates.

That is a risky position. We can’t assume that a future superintelligence will carry forward our values and goals, unless we take enormous care to build it that way. Sure, human values and goals are often far from perfect, but they have improved over our history through the accumulation of principles such as human rights. Even if we’re sometimes loath to acknowledge it, the human story is one of progress.

Imagine if our non-biological descendants had no inner subjective experience—the weird thing called consciousness that enables us to marvel at a scientific theory or feel a sense of achievement at having sweated our way to success at some ambitious task. What if they were to solve the deepest riddles of the universe yet feel no sense of wonder at what they’d done?

Over the long span of the future, AI needs to serve the interests of humanity, not the other way around. Humans won’t be here forever, but let’s make sure that the future of intelligence represents a controlled evolution, not a radical breach, of the values we’ve built and the wisdom we’ve earned over millennia.

There is a lot we can do. We need to avoid, for instance, letting commercial or geopolitical pressure drive reckless haste in developing powerful AIs. We need to think and debate very carefully the prospect of giving AIs the power to form their own goals or pursue very general goals on our behalf. Giving an AI the instruction to ‘go out and make me a pile of money’ isn’t going to end well. At some point, the discussion will become less about intelligence and more about agency and the ability to achieve actual outcomes in the world.

Ensuring that a future AGI does not leave us behind will likely mean putting some limitations on development—even temporarily—while we think through the implications of the technology and find ways to keep it tethered to human values and aspirations. As the neural network pioneer Geoffrey Hinton has put it, ‘There is not a good track record of less intelligent things controlling things of greater intelligence.’

I’m certainly not looking forward to any future in which AI treats humans like pets, as Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak once speculated.

With that in mind, this is the first piece in a new Strategist series that will look at artificial intelligence over the coming months as part of this ongoing and vital debate.

ASPI is a national security and international policy think tank, so we’ll be focusing on security and international dimensions. But what I’ve outlined here is really the ultimate human security issue, which is our global future and our ability to continue to live meaningful lives. This is the biggest question we are facing right now and arguably the biggest we have ever faced.

If a Chinese tech firm wants to venture into generative artificial intelligence it is bound to face significant hurdles arising from stringent government control, at least according to popular perceptions. China was, after all, among the first countries to introduce legislation regulating the technology. But a closer look at the so-called interim measures on AI indicates that far from hampering the industry, China’s government is actively seeking to bolster it.

This shouldn’t be surprising. Already a global leader in AI (trailing only the United States), China has big ambitions in the sector—and the means to ensure that its legal and regulatory landscape encourages and facilitates indigenous innovation.

The interim measures on generative AI reflect this strategic motivation. To be sure, a preliminary draft of the legislation released by the Cyberspace Administration of China included some encumbering provisions. For example, it would have required providers of AI services to ensure that the training data and the model outputs be ‘true and accurate’, and it gave firms just three months to recalibrate foundational models producing prohibited content.

But these rules were watered down significantly in the final legislation. The interim measures also significantly narrowed the scope of application, targeting only public-facing companies and mandating content-based security assessment solely for those wielding influence over public opinion.

While securing approval from the regulatory authorities does entail additional costs and a degree of uncertainty, there’s no reason to think that Chinese tech giants—with their deep pockets and strong capacity for compliance—will be deterred. Nor is there reason to think that the Cyberspace Administration would seek to create unnecessary roadblocks: just two weeks after the interim measures went into effect, it gave the green light to eight companies, including Baidu and SenseTime, to launch their chatbots.

Overall, the interim measures advance a cautious and tolerant regulatory approach, which should assuage industry concerns over potential policy risks. The legislation even includes provisions explicitly encouraging collaboration among major stakeholders in the AI supply chain, reflecting a recognition that technological innovation depends on exchanges between government, industry and academia.

So, while China was an early mover in regulating generative AI, it is also highly supportive of the technology and the companies developing it. Chinese AI firms might even have a competitive advantage over their American and European counterparts, which are facing strong regulatory headwinds and proliferating legal challenges.

In the European Union, the Digital Services Act, which entered into force last year, imposes a raft of transparency and due-diligence obligations on large online platforms, with massive penalties for violators. The General Data Protection Regulation—the world’s toughest data privacy and security law—is also threatening to trip up AI firms. Already, OpenAI—the company behind ChatGPT—is under scrutiny in France, Ireland, Italy, Poland and Spain for alleged breaches of GDPR provisions, with the Italian authorities earlier this year going so far as to halt the firm’s operations temporarily.

The EU’s AI Act, which is expected to be finalised by the end of this year, is likely to saddle firms with a host of onerous pre-launch commitments for AI applications. For example, the latest draft endorsed by the European Parliament would require firms to provide a detailed summary of the copyrighted material used to train models—a requirement that could leave AI developers vulnerable to lawsuits.

American firms know firsthand how burdensome such legal proceedings can be. The US federal government has yet to introduce comprehensive AI regulation, and existing state and sectoral regulation is patchy. But prominent AI companies such as OpenAI, Google and Meta are grappling with private litigation related to everything from copyright infringement to data privacy violations, defamation and discrimination.

The potential costs of losing these legal battles are high. Beyond hefty fines, firms might have to adjust their operations to meet stringent remedies. In an effort to pre-empt further litigation, OpenAI is already seeking to negotiate content-licensing agreements with leading news outlets for AI training data.

Chinese firms, by contrast, can probably expect both regulatory agencies and courts—following official directives from the central government—to take a lenient approach to AI-related legal infringements. That is what happened when the consumer tech industry was starting out.

None of this is to say that China’s growth-centric regulatory approach is the right one. On the contrary, the government’s failure to protect the legitimate interests of Chinese citizens could have long-term consequences for productivity and growth, and shielding large tech firms from accountability threatens to entrench further their dominant market position, ultimately stifling innovation. Nonetheless, it appears clear that, at least in the short term, Chinese regulation will act as an enabler, rather than an impediment, for the country’s AI firms.

Sorry, no posts matched your criteria